The wounds are still fresh. The art world continues to mourn the passing of Peter Clarke, the great painter, poet and writer who passed away earlier this year. Clarke inspired people around the globe from his township home in Ocean View. He and his family were forcibly moved to this place with the cruel name, far away from the seaside, in the 1960s under the Group Areas Act.

Clarke drew inspiration from his community as he depicted the social and political experiences of South Africans under apartheid. A largely self-taught artist, he captured the struggles and successes of his community, those who survived under difficult circumstances. He was dignified and humble.

Internationally renowned artist but also a friend, uncle and brother whose art and life became entwined with the people he knew and loved: Veteran poet James Matthews, photographer George Hallett, local artist Lionel Davis… to name but a few. His memory lives on through his work but for many it’s the personal anecdotes that tell the real story of the man behind the paintings. One account, particularly moving, has been written by Nina Callaghan on the Remembering Peter Clarke Facebook page, a young woman who grew up surrounded by these legends.

Peter Clarke. Coming and going (1960). Oil. 511 cm x 409 cm. Private collection.

A Writer Remembers

“We only went to Ocean View to visit one person really, Uncle Peter and sometimes Aunty Gladys. It was so far we had to make a day of it. Sometimes we’d go on the way to camp at Soetwater. Other times the rest of the poetry spewing, wine swigging comrades would also be there, outdoing each other with unsteady pregnant pauses, twisted verses and pained love all decked out in lots of leather, corduroys and polo necks. Uncle Peter sometimes wore a silk cravat.

On those days, when Aunty Gladys’ yard was full I’d get anxious before the party even started because I knew we’d leave with my mother furious, at my father for drinking too much, or because of some or other untoward comment from James or Aubrey who audaciously wanted a lift back home to Athlone – in our car.

Uncle Peter would snigger, his shoulders shaking, stroke his bok baard, lift his one eyebrow just so, his top lip all pointy and smiling at the same time and in his best English accent say, “Oh come on chaps.” I remember his house smelling of pepper. Not the kind that made you sneeze, but something rich and spicy and tonal.

The best visits were when we’d come away with presents. Silver and perlemoen shell earrings for my mother that she kept in a dark wooden jewelry box uncle Peter also made. My favourites were the candles. I’d watch the blue blocks melt into orange and I’d burn them rarely and just for me at the dining room table. They were like paintings come to life,”

Son of A Domestic Worker

Peter Clarke at Paaden Kloof.

Born 2 June, 1929, Clarke grew up in Cardiff Road, Simon’s Town. His mother was a domestic worker, and his father worked as a labourer in the dockyard. Both his parents were avid readers, and instilled in Clarke a love for literature. During the forced removals under the Group Areas Act of the 1950s and 60s many families were evicted from the seaside, naval base town and dumped in Ocean View, including Clarke’s.

His career as a poet and artist exceeds six decades. His visual work was influenced by a wide variety of artists and movements, from Gerard Sekoto to Picasso. From the vibrancy of the African-American artists of the Harlem Renaissance to the flourishes of Japanese woodcuts or the intensity of Mexican muralists.

Clarke attended art classes in Woodstock, and worked as a store assistant at the Cape Town dockyard before devoting himself to his art. His first exhibition was held in 1957 and arranged by his life-long friend, the iconic poet and writer James Matthews:

“When Peter started out as a young artist, galleries refused to accept his work. I was a journalist working at Golden City Post and without the headquarters in Joburg knowing about it, I turned the newsroom into an art gallery. That was Peter’s first exhibition. And of course he progressed,” said Matthews.

“Yes, he and James Matthews were always together,” said photographer George Hallett. “One day I went by and I asked him, ‘What are you cooking?’ and he said to me ‘The Clarkes never cook, they create.’ That kind of sophistication you rarely find with ordinary people”.

While best known as a printmaker, Clarke is also highly regarded for his linocut and woodblock techniques. With a doctorate in literature, words played an important role in his visual work. However, his commitment to the arts stretched far beyond his paintings and writing. He would hold workshops with local youth, arrange exhibitions and engage with aspiring artists at any opportunity.

“We need to remember Peter, especially in the black community, because today we have very few role models. Gangsterism has taken over in so many places but there is a need for us to have those role models. We need to uplift our community,” said Lionel Davis, a loyal friend and artist who still trains young aspiring artists all over South Africa.

Listening To Distant Thunder (1970). Oil and sand on board. Johannesburg Art Gallery

A Very Important Man

Despite being an internationally praised artist, Clarke remained in his matchbox, semi-detached home in Ocean View. This is where he found his inspiration. His community was his art. One of his works Coming and Going (1960) portrays the trauma of the forced removals. Callaghan describes her memories:

I never used to think his paintings were that special. They seemed to be everywhere and a constant feature of my childhood, crowded on the short walls of 18a Thornton Road. The trees in them were so desolate, the men were usually drinking and there always seemed to be a terrible wind that pushed people about. They made my four-year-old self sad. But my dad was always so proud of them, and boasted every time someone new came to visit, ‘Done by my friend, (pause) (sway) Peter Clarke,’ the last consonant sharp and posh, like he was a very important man.

I didn’t think they were back then, Uncle Peter, George Hallet, James Matthews. They always made my mother cross and talked long into the night about the fucking bastards and a revolution. Now they’re respected elders, their treasures of love and struggle curating a chapter in history.

In 2005, Clarke was awarded the Order of Ikhamanga, by former President Thabo Mbeki and in 2010 he was presented with a lifetime achievement award. He exhibited locally and internationally including Dakar, London, Paris and Barbados.

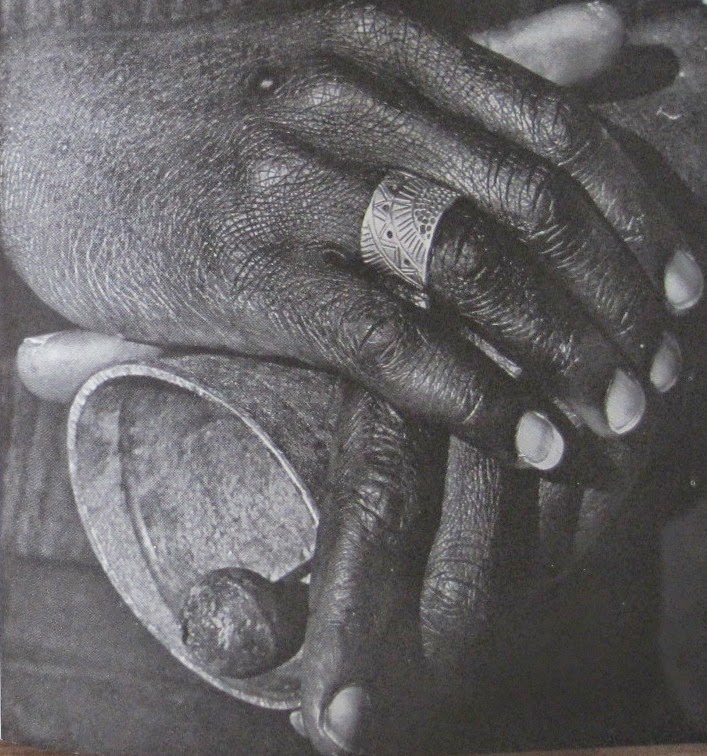

Peter Hands by George Hallett

A precise & well-wrtitten post. Thanks heaps for sharing it.

I do not even know how I ended up here, but I thought this post was good. I don’t know who you are but certainly you’re going to a famous blogger if you aren’t already Cheers!

Whether you believe in God or not, this is a must-read message!!!

Throughout time, we can see how we have been slowly conditioned to come to this point where we are on the verge of a cashless society. Did you know that the Bible foretold of this event almost 2,000 years ago?

In Revelation 13:16-18, we read,

“He (the false prophet who decieves many by his miracles) causes all, both small and great, rich and poor, free and slave, to receive a mark on their right hand or on their foreheads, and that no one may buy or sell except one who has the mark or the name of the beast, or the number of his name.

Here is wisdom. Let him who has understanding calculate the number of the beast, for it is the number of a man: His number is 666.”

Referring to the last generation, this could only be speaking of a cashless society. Why? Revelation 13:17 tells us that we cannot buy or sell unless we receive the mark of the beast. If physical money was still in use, we could buy or sell with one another without receiving the mark. This would contradict scripture that states we need the mark to buy or sell!

These verses could not be referring to something purely spiritual as scripture references two physical locations (our right hand or forehead) stating the mark will be on one “OR” the other. If this mark was purely spiritual, it would indicate only in one place.

This is where it really starts to come together. It is shocking how accurate the Bible is concerning the implatnable RFID microchip. These are notes from a man named Carl Sanders who worked with a team of engineers to help develop this RFID chip

“Carl Sanders sat in seventeen New World Order meetings with heads-of-state officials such as Henry Kissinger and Bob Gates of the C.I.A. to discuss plans on how to bring about this one-world system. The government commissioned Carl Sanders to design a microchip for identifying and controlling the peoples of the world—a microchip that could be inserted under the skin with a hypodermic needle (a quick, convenient method that would be gradually accepted by society).

Carl Sanders, with a team of engineers behind him, with U.S. grant monies supplied by tax dollars, took on this project and designed a microchip that is powered by a lithium battery, rechargeable through the temperature changes in our skin. Without the knowledge of the Bible (Brother Sanders was not a Christian at the time), these engineers spent one-and-a-half-million dollars doing research on the best and most convenient place to have the microchip inserted.

Guess what? These researchers found that the forehead and the back of the hand (the two places the Bible says the mark will go) are not just the most convenient places, but are also the only viable places for rapid, consistent temperature changes in the skin to recharge the lithium battery. The microchip is approximately seven millimeters in length, .75 millimeters in diameter, about the size of a grain of rice. It is capable of storing pages upon pages of information about you. All your general history, work history, crime record, health history, and financial data can be stored on this chip.

Brother Sanders believes that this microchip, which he regretfully helped design, is the “mark” spoken about in Revelation 13:16–18. The original Greek word for “mark” is “charagma,” which means a “scratch or etching.” It is also interesting to note that the number 666 is actually a word in the original Greek. The word is “chi xi stigma,” with the last part, “stigma,” also meaning “to stick or prick.” Carl believes this is referring to a hypodermic needle when they poke into the skin to inject the microchip.”

Mr. Sanders asked a doctor what would happen if the lithium contained within the RFID microchip leaked into the body. The doctor replied by saying a terrible sore would appear in that location. This is what the book of Revelation says:

“And the first (angel) went, and poured out his vial on the earth; and there fell a noisome and grievous sore on the men which had the mark of the beast, and on them which worshipped his image” (Revelation 16:2).

You can read more about it here–and to also understand the mystery behind the number 666: https://2ruth.org/rfid-mark-of-the-beast-666-revealed/

The third angel’s warning in Revelation 14:9-11 states,

“Then a third angel followed them, saying with a loud voice, ‘If anyone worships the beast and his image, and receives his mark on his forehead or on his hand, he himself shall also drink of the wine of the wrath of God, which is poured out full strength into the cup of His indignation. He shall be tormented with fire and brimstone in the presence of the holy angels and in the presence of the Lamb. And the smoke of their torment ascends forever and ever; and they have no rest day or night, who worship the beast and his image, and whoever receives the mark of his name.'”

Who is Barack Obama, and why is he still in the public scene?

So what’s in the name? The meaning of someone’s name can say a lot about a person. God throughout history has given names to people that have a specific meaning tied to their lives. How about the name Barack Obama? Let us take a look at what may be hiding beneath the surface.

Jesus says in Luke 10:18, “…I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven.”

The Hebrew Strongs word (H1299) for “lightning”: “bârâq” (baw-rawk)

In Isaiah chapter 14, verse 14, we read about Lucifer (Satan) saying in his heart:

“I will ascend above the heights of the clouds, I will be like the Most High.”

In the verses in Isaiah that refer directly to Lucifer, several times it mentions him falling from the heights or the heavens. The Hebrew word for the heights or heavens used here is Hebrew Strongs 1116: “bamah”–Pronounced (bam-maw’)

In Hebrew, the letter “Waw” or “Vav” is often transliterated as a “U” or “O,” and it is primarily used as a conjunction to join concepts together. So to join in Hebrew poetry the concept of lightning (Baraq) and a high place like heaven or the heights of heaven (Bam-Maw), the letter “U” or “O” would be used. So, Baraq “O” Bam-Maw or Baraq “U” Bam-Maw in Hebrew poetry similar to the style written in Isaiah, would translate literally to “Lightning from the heights.” The word “Satan” in Hebrew is a direct translation, therefore “Satan.”

So when Jesus told His disciples in Luke 10:18 that He beheld Satan fall like lightning from heaven, if this were to be spoken by a Jewish Rabbi today influenced by the poetry in the book of Isaiah, he would say these words in Hebrew–the words of Jesus in Luke 10:18 as, And I saw Satan as Baraq O Bam-Maw.

The names of both of Obama’s daughters are Malia and Natasha. If we were to write those names backward (the devil does things in reverse) we would get “ailam ahsatan”. Now if we remove the letters that spell “Alah” (Allah being the false god of Islam), we get “I am Satan”. Coincidence? I don’t think so.

Obama’s campaign logo when he ran in 2008 was a sun over the horizon in the west, with the landscape as the flag of the United States. In Islam, they have their own messiah that they are waiting for called the 12th Imam, or the Mahdi (the Antichrist of the Bible), and one prophecy concerning this man’s appearance is the sun rising in the west.

“Then I saw another angel flying in the midst of heaven, having the everlasting gospel to preach to those who dwell on the earth—to every nation, tribe, tongue, and people— saying with a loud voice, ‘Fear God and give glory to Him, for the hour of His judgment has come; and worship Him who made heaven and earth, the sea and springs of water.'” (Revelation 14:6-7)

Why have the word’s of Jesus in His Gospel accounts regarding His death, burial, and resurrection, been translated into over 3,000 languages, and nothing comes close? The same God who formed the heavens and earth that draws all people to Him through His creation, likewise has sent His Word to the ends of the earth so that we may come to personally know Him to be saved in spirit and in truth through His Son Jesus Christ.

Jesus stands alone among the other religions that say to rightly weigh the scales of good and evil and to make sure you have done more good than bad in this life. Is this how we conduct ourselves justly in a court of law? Bearing the image of God, is this how we project this image into reality?

Our good works cannot save us. If we step before a judge, being guilty of a crime, the judge will not judge us by the good that we have done, but rather by the crimes we have committed. If we as fallen humanity, created in God’s image, pose this type of justice, how much more a perfect, righteous, and Holy God?

God has brought down His moral laws through the 10 commandments given to Moses at Mt. Siani. These laws were not given so we may be justified, but rather that we may see the need for a savior. They are the mirror of God’s character of what He has put in each and every one of us, with our conscious bearing witness that we know that it is wrong to steal, lie, dishonor our parents, murder, and so forth.

We can try and follow the moral laws of the 10 commandments, but we will never catch up to them to be justified before a Holy God. That same word of the law given to Moses became flesh about 2,000 years ago in the body of Jesus Christ. He came to be our justification by fulfilling the law, living a sinless perfect life that only God could fulfill.

The gap between us and the law can never be reconciled by our own merit, but the arm of Jesus is stretched out by the grace and mercy of God. And if we are to grab on, through faith in Him, He will pull us up being the one to justify us. As in the court of law, if someone steps in and pays our fine, even though we are guilty, the judge can do what is legal and just and let us go free. That is what Jesus did almost 2,000 years ago on the cross. It was a legal transaction being fulfilled in the spiritual realm by the shedding of His blood.

For God takes no pleasure in the death of the wicked (Ezekiel 18:23). This is why in Isaiah chapter 53, where it speaks of the coming Messiah and His soul being a sacrifice for our sins, why it says it pleased God to crush His only begotten Son.

This is because the wrath that we deserve was justified by being poured out upon His Son. If that wrath was poured out on us, we would all perish to hell forever. God created a way of escape by pouring it out on His Son whose soul could not be left in Hades but was raised and seated at the right hand of God in power.

So now when we put on the Lord Jesus Christ (Romans 13:14), God no longer sees the person who deserves His wrath, but rather the glorious image of His perfect Son dwelling in us, justifying us as if we received the wrath we deserve, making a way of escape from the curse of death–now being conformed into the image of the heavenly man in a new nature, and no longer in the image of the fallen man Adam.

Now what we must do is repent and put our trust and faith in the savior, confessing and forsaking our sins, and to receive His Holy Spirit that we may be born again (for Jesus says we must be born again to enter the Kingdom of God–John chapter 3). This is not just head knowledge of believing in Jesus, but rather receiving His words, taking them to heart, so that we may truly be transformed into the image of God. Where we no longer live to practice sin, but rather turn from our sins and practice righteousness through faith in Him in obedience to His Word by reading the Bible.

Our works cannot save us, but they can condemn us; it is not that we earn our way into everlasting life, but that we obey our Lord Jesus Christ:

“And having been perfected, He became the author of eternal salvation to all who obey Him.” (Hebrews 5:9)

“Now I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away. Also there was no more sea. Then I, John, saw the holy city, New Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from heaven saying, ‘Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men, and He will dwell with them, and they shall be His people. God Himself will be with them and be their God. And God will wipe away every tear from their eyes; there shall be no more death, nor sorrow, nor crying. There shall be no more pain, for the former things have passed away.’

Then He who sat on the throne said, ‘Behold, I make all things new.’ And He said to me, ‘Write, for these words are true and faithful.’

And He said to me, ‘It is done! I am the Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End. I will give of the fountain of the water of life freely to him who thirsts. He who overcomes shall inherit all things, and I will be his God and he shall be My son. But the cowardly, unbelieving, abominable, murderers, sexually immoral, sorcerers, idolaters, and all liars shall have their part in the lake which burns with fire and brimstone, which is the second death.'” (Revelation 21:1-8).

Please tell me more about this. May I ask you a question?

Please provide me with more details on the topic

A very awesome blog post. We are really grateful for your blog post. You will find a lot of approaches after visiting your post.

okbet philippines

I was very pleased to find this web-site.I wanted to thanks for your time for this wonderful read!! I definitely enjoying every little bit of it and I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you blog post.

F*ckin’ remarkable issues here. I’m very satisfied to look your article. Thank you so much and i’m taking a look ahead to touch you. Will you please drop me a mail?

Loving the info on this web site, you have done outstanding job on the articles.

Very interesting subject, thank you for posting.

After study a few of the blog posts on your website now, and I truly like your way of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website list and will be checking back soon. Pls check out my web site as well and let me know what you think.

I was just seeking this info for some time. After 6 hours of continuous Googleing, at last I got it in your website. I wonder what’s the lack of Google strategy that don’t rank this type of informative sites in top of the list. Usually the top sites are full of garbage.

Hey! This post couldn’t be written any better! Reading through this post reminds me of my old room mate! He always kept talking about this. I will forward this write-up to him. Fairly certain he will have a good read. Thanks for sharing!

I like this web blog so much, bookmarked.

Write more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seems as though you relied on the video to make your point. You definitely know what youre talking about, why throw away your intelligence on just posting videos to your weblog when you could be giving us something enlightening to read?

Very interesting topic, thanks for posting.

I think this website holds some very great information for everyone. “The best friend is the man who in wishing me well wishes it for my sake.” by Aristotle.

Greetings! I’ve been reading your website for a long time now and finally got the bravery to go ahead and give you a shout out from Lubbock Tx! Just wanted to say keep up the fantastic work!

You are my aspiration, I possess few web logs and very sporadically run out from to brand.

What i do not understood is in fact how you’re now not actually much more neatly-liked than you might be now. You are so intelligent. You realize therefore considerably on the subject of this subject, made me in my opinion believe it from numerous numerous angles. Its like men and women are not interested unless it¦s something to do with Lady gaga! Your own stuffs outstanding. All the time maintain it up!

I have been exploring for a bit for any high-quality articles or blog posts in this kind of space . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this website. Reading this information So i am glad to exhibit that I have a very just right uncanny feeling I found out exactly what I needed. I so much indubitably will make certain to don’t overlook this website and give it a glance on a relentless basis.

Great write-up, I am regular visitor of one?¦s web site, maintain up the nice operate, and It is going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.

I am typically to blogging and i really respect your content. The article has actually peaks my interest. I am going to bookmark your website and hold checking for brand spanking new information.

you may have an amazing blog right here! would you like to make some invite posts on my blog?

Its such as you read my thoughts! You seem to grasp a lot approximately this, like you wrote the e book in it or something. I think that you just can do with some percent to drive the message home a little bit, however instead of that, this is wonderful blog. A great read. I will certainly be back.

Good day very cool web site!! Guy .. Beautiful .. Superb .. I’ll bookmark your blog and take the feeds alsoKI’m glad to search out numerous helpful information right here in the submit, we’d like develop more techniques on this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

You are a very clever person!

Thank you, I have just been searching for info about this subject for ages and yours is the best I have discovered so far. But, what about the bottom line? Are you certain about the supply?

I love it when people come together and share opinions, great blog, keep it up.

I have been browsing online greater than three hours these days, yet I never found any fascinating article like yours. It is beautiful worth enough for me. In my view, if all site owners and bloggers made good content as you did, the web might be a lot more helpful than ever before. “Dignity is not negotiable. Dignity is the honor of the family.” by Vartan Gregorian.

Respect to post author, some fantastic entropy.

I conceive this site has got very good composed content posts.

I have been exploring for a bit for any high-quality articles or weblog posts in this sort of space . Exploring in Yahoo I finally stumbled upon this website. Reading this information So i am glad to show that I’ve an incredibly just right uncanny feeling I found out exactly what I needed. I most certainly will make certain to do not omit this site and provides it a glance on a relentless basis.

What’s Happening i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve found It absolutely helpful and it has helped me out loads. I hope to contribute & aid other users like its helped me. Good job.

An attention-grabbing discussion is value comment. I think that you must write extra on this topic, it might not be a taboo topic but generally people are not enough to talk on such topics. To the next. Cheers

Yay google is my world beater helped me to find this outstanding site! .

Thanks, I have just been searching for information approximately this subject for ages and yours is the best I have found out so far. But, what about the conclusion? Are you positive in regards to the source?

Have you ever thought about publishing an e-book or guest authoring on other websites? I have a blog based on the same subjects you discuss and would love to have you share some stories/information. I know my visitors would appreciate your work. If you’re even remotely interested, feel free to send me an e-mail.

I have been exploring for a little for any high quality articles or blog posts on this sort of area . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this web site. Reading this info So i’m happy to convey that I’ve an incredibly good uncanny feeling I discovered exactly what I needed. I most certainly will make certain to don’t forget this web site and give it a look regularly.

Excellent read, I just passed this onto a friend who was doing some research on that. And he just bought me lunch since I found it for him smile So let me rephrase that: Thank you for lunch!

You have brought up a very great details , regards for the post.

I’m especially interested in the content of these articles, they’re great. Keep going, I’m rooting for you in your next work.

my homepage : okbet review

This web site is really a walk-through for all of the info you wanted about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse here, and you’ll definitely discover it.

Nice post. I learn something more challenging on different blogs everyday. It will always be stimulating to read content from other writers and practice a little something from their store. I’d prefer to use some with the content on my blog whether you don’t mind. Natually I’ll give you a link on your web blog. Thanks for sharing.

Hello there, I discovered your site by way of Google while looking for a related matter, your website came up, it appears to be like good. I have bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

I got what you intend, thanks for putting up.Woh I am lucky to find this website through google.

What i don’t realize is in reality how you’re not actually much more neatly-appreciated than you might be right now. You are so intelligent. You know therefore significantly on the subject of this topic, produced me in my opinion imagine it from numerous various angles. Its like women and men don’t seem to be fascinated except it is one thing to do with Woman gaga! Your own stuffs nice. Always deal with it up!

Very great information can be found on website.

What’s Happening i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve found It absolutely useful and it has helped me out loads. I hope to contribute & aid other users like its aided me. Great job.

신림노래방알바

신림노래방알바

Рингобет (RibgoBet) – официальный сайт букмекерской конторы в Казахстане. Вход и регистрация у букмекера. Ставки на БК Рингобет – футбол, хоккей, теннис.

강남하이퍼블릭

강남하이퍼블릭

Thank you for your good blog종로노래방알바

Thank you for your good blog종로노래방알바

Saved as a favorite, I really like your blog!

What’s Going down i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve found It absolutely useful and it has helped me out loads. I’m hoping to contribute & assist different users like its aided me. Good job.

Hello there, I found your web site by way of Google at the same time as looking for a comparable subject, your site came up, it seems to be good. I’ve bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

I don’t even know how I ended up here, but I thought this post was good. I don’t know who you are but definitely you’re going to a famous blogger if you aren’t already 😉 Cheers!

Fantastic beat ! I wish to apprentice at the same time as you amend your web site, how could i subscribe for a weblog website? The account helped me a appropriate deal. I had been a little bit familiar of this your broadcast provided bright transparent idea

You are my aspiration, I have few web logs and often run out from to post .

I wanted to post you one little bit of remark to be able to say thank you again relating to the remarkable secrets you’ve shared on this website. It was certainly incredibly generous with you to provide publicly just what many people could possibly have sold as an e book to get some money for themselves, principally considering the fact that you could have done it in the event you decided. Those guidelines in addition served as a great way to comprehend other individuals have the identical eagerness similar to my very own to know way more on the topic of this issue. I’m certain there are some more fun moments up front for folks who looked at your blog.

I?¦ve recently started a blog, the information you provide on this website has helped me greatly. Thanks for all of your time & work.

Hey! This post could not be written any better! Reading this post reminds me of my old room mate! He always kept chatting about this. I will forward this write-up to him. Pretty sure he will have a good read. Thank you for sharing!

Sweet internet site, super design and style, rattling clean and utilize genial.

I have been examinating out some of your articles and i must say pretty good stuff. I will make sure to bookmark your website.

Great goods from you, man. I have understand your stuff previous to and you are just too wonderful. I actually like what you have acquired here, certainly like what you are stating and the way in which you say it. You make it entertaining and you still care for to keep it sensible. I cant wait to read much more from you. This is really a great website.

Thanks for your write-up on the vacation industry. I’d personally also like contribute that if you are a senior thinking about traveling, its absolutely important to buy travel cover for seniors. When traveling, older persons are at biggest risk being in need of a healthcare emergency. Obtaining right insurance plan package in your age group can safeguard your health and provide you with peace of mind.

The platform’s user reviews have helped me make informed decisions when considering a purchase.

Many internet sabong tips and suggestions are available, but this is the most original and traditional advice you will ever read!!! Want to know more about the site? visit here —>> Online Sabong Tips: How to Increase your Winnings Online

We are a group of volunteers and starting a new scheme in our community. Your website offered us with valuable info to work on. You’ve done an impressive job and our whole community will be grateful to you.

hello!,I really like your writing so much! share we communicate extra approximately your article on AOL? I require an expert on this space to unravel my problem. May be that’s you! Having a look forward to peer you.

WONDERFUL Post.thanks for share..extra wait .. ?

Thanks a lot for sharing this with all of us you really know what you’re talking about! Bookmarked. Please also visit my web site =). We could have a link exchange contract between us!

hello!,I like your writing so much! share we communicate more about your post on AOL? I need an expert on this area to solve my problem. Maybe that’s you! Looking forward to see you.

A powerful share, I simply given this onto a colleague who was doing a bit of analysis on this. And he actually purchased me breakfast because I discovered it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the treat! However yeah Thnkx for spending the time to discuss this, I really feel strongly about it and love studying more on this topic. If attainable, as you become expertise, would you mind updating your weblog with extra details? It is highly helpful for me. Big thumb up for this blog publish!

I do agree with all the ideas you’ve presented in your post. They are very convincing and will definitely work. Still, the posts are too short for newbies. Could you please extend them a little from next time? Thanks for the post.

I believe one of your advertisements caused my web browser to resize, you might want to put that on your blacklist.

The article acknowledges potential biases and limitations in the data.

What i do not realize is actually how you are not actually much more well-liked than you might be now. You’re very intelligent. You realize therefore significantly relating to this subject, produced me personally consider it from so many varied angles. Its like men and women aren’t fascinated unless it?s one thing to accomplish with Lady gaga! Your own stuffs great. Always maintain it up!

It is in point of fact a nice and useful piece of info. I am happy that you simply shared this helpful info with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.|

I always used to read post in news papers but now as I am a user of net so from now I am using net for posts, thanks to web.|

My partner and I stumbled over here by a different page and thought I might check things out. I like what I see so i am just following you. Look forward to looking over your web page for a second time.|

Your style is unique compared to other folks I’ve read stuff from. Thank you for posting when you have the opportunity, Guess I’ll just bookmark this blog.|

Amazing issues here. I’m very glad to look your post. Thank you so much and I’m having a look ahead to touch you. Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?|

Excellent goods from you, man. I’ve understand your stuff previous to and you’re just extremely great. I really like what you’ve acquired here, certainly like what you’re stating and the way in which you say it. You make it entertaining and you still care for to keep it smart. I can’t wait to read much more from you. This is really a tremendous website.|

I have to thank you for the efforts you’ve put in penning this blog. I really hope to see the same high-grade content by you in the future as well. In truth, your creative writing abilities has inspired me to get my own, personal site now ;)|

Howdy just wanted to give you a quick heads up and let you know a few of the images aren’t loading correctly. I’m not sure why but I think its a linking issue. I’ve tried it in two different web browsers and both show the same outcome.|

Terrific work! That is the type of information that should be shared around the internet. Shame on Google for no longer positioning this publish upper! Come on over and visit my website . Thank you =)|

Since the admin of this web site is working, no doubt very rapidly it will be well-known, due to its quality contents.|

Heya superb website! Does running a blog similar to this require a lot of work? I have virtually no expertise in coding but I was hoping to start my own blog soon. Anyhow, should you have any suggestions or tips for new blog owners please share. I understand this is off subject but I just wanted to ask. Thanks!|

Greetings! Very useful advice in this particular post! It’s the little changes that make the biggest changes. Many thanks for sharing!|

great issues altogether, you just received a emblem new reader. What might you suggest in regards to your put up that you made a few days in the past? Any certain?|

Definitely believe that that you stated. Your favorite justification seemed to be at the net the simplest factor to keep in mind of. I say to you, I certainly get annoyed whilst people think about worries that they plainly don’t recognise about. You managed to hit the nail upon the top and also outlined out the whole thing with no need side effect , other people can take a signal. Will likely be again to get more. Thank you|

Hello there, You’ve done a great job. I’ll definitely digg it and personally recommend to my friends. I’m sure they’ll be benefited from this web site.|

I’m curious to find out what blog platform you have been working with? I’m having some small security issues with my latest blog and I’d like to find something more safe. Do you have any solutions?|

I always spent my half an hour to read this weblog’s articles everyday along with a cup of coffee.|

Every weekend i used to visit this website, as i wish for enjoyment, since this this website conations truly pleasant funny data too.|

Thanks for finally talking about > blog_title < Loved it!|

Hi, after reading this amazing paragraph i am also delighted to share my experience here with colleagues.|

What’s up to every one, it’s in fact a nice for me to pay a quick visit this web page, it includes helpful Information.|

Hi there! I know this is kinda off topic nevertheless I’d figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in exchanging links or maybe guest writing a blog article or vice-versa? My blog addresses a lot of the same subjects as yours and I think we could greatly benefit from each other. If you happen to be interested feel free to shoot me an e-mail. I look forward to hearing from you! Excellent blog by the way!|

Hello Dear, are you really visiting this website daily, if so after that you will absolutely get good know-how.|

Fantastic beat ! I wish to apprentice while you amend your site, how can i subscribe for a blog site? The account aided me a acceptable deal. I had been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast provided bright clear concept|

Excellent pieces. Keep posting such kind of info on your site. Im really impressed by it.

Wow, that’s what I was seeking for, what a material! present here at this website, thanks admin of this web site.|

I hardly create remarks, but i did a few searching and wound up here BLOG_TITLE. And I actually do have 2 questions for you if you don’t mind. Is it simply me or does it look as if like some of these responses appear as if they are left by brain dead people? 😛 And, if you are writing at other online social sites, I would like to follow everything fresh you have to post. Could you list of the complete urls of your shared pages like your linkedin profile, Facebook page or twitter feed?|

Howdy! I could have sworn I’ve been to this site before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyhow, I’m definitely delighted I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back often!|

Great delivery. Solid arguments. Keep up the great work.|

Hurrah, that’s what I was searching for, what a material! present here at this web site, thanks admin of this website.|

It’s hard to come by well-informed people for this subject, however, you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks|

There is certainly a great deal to find out about this topic. I like all of the points you have made.|

I almost never leave a response, however I read some of the remarks here BLOG_TITLE. I do have a couple of questions for you if it’s allright. Is it simply me or do a few of the remarks come across as if they are left by brain dead people? 😛 And, if you are writing at additional social sites, I’d like to follow everything fresh you have to post. Would you make a list of every one of all your social pages like your twitter feed, Facebook page or linkedin profile?|

Thank you for the good writeup. It actually used to be a entertainment account it. Look advanced to more added agreeable from you! By the way, how can we communicate?|

Hello! Do you use Twitter? I’d like to follow you if that would be okay. I’m undoubtedly enjoying your blog and look forward to new posts.|

After looking at a handful of the articles on your web site, I honestly like your technique of writing a blog. I saved it to my bookmark webpage list and will be checking back in the near future. Please check out my web site too and let me know what you think.|

What i do not realize is in reality how you’re not actually much more well-liked than you might be right now. You’re so intelligent. You understand therefore considerably in terms of this subject, made me personally believe it from numerous numerous angles. Its like women and men are not involved until it is one thing to accomplish with Girl gaga! Your personal stuffs outstanding. Always handle it up!|

I have been exploring for a little bit for any high quality articles or blog posts in this sort of space . Exploring in Yahoo I finally stumbled upon this web site. Reading this information So i am happy to exhibit that I’ve a very excellent uncanny feeling I came upon just what I needed. I so much undoubtedly will make certain to don?t disregard this site and provides it a look regularly.|

Everyone loves it whenever people get together and share ideas. Great blog, keep it up!|

Heya! I’m at work surfing around your blog from my new iphone 3gs! Just wanted to say I love reading through your blog and look forward to all your posts! Keep up the excellent work!|

I do accept as true with all the concepts you’ve offered in your post. They’re really convincing and will certainly work. Nonetheless, the posts are very short for newbies. May you please lengthen them a bit from next time? Thank you for the post.

This piece of writing gives clear idea designed for the new people of blogging, that really how to do blogging.|

My brother suggested I may like this website. He was once totally right. This post truly made my day. You cann’t believe just how much time I had spent for this info! Thanks!|

No matter if some one searches for his required thing, so he/she needs to be available that in detail, so that thing is maintained over here.|

It’s an remarkable post for all the online people; they will get advantage from it I am sure.|

Just want to say your article is as astounding. The clarity in your post is just excellent and i could assume you’re an expert on this subject. Well with your permission let me to grab your feed to keep updated with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please continue the rewarding work.|

Excellent post however , I was wondering if you could write a litte more on this topic? I’d be very grateful if you could elaborate a little bit more. Appreciate it!|

You actually make it seem so easy with your presentation but I find this topic to be really something that I think I would never understand. It seems too complex and extremely broad for me. I’m looking forward for your next post, I will try to get the hang of it!|

This is the perfect webpage for anybody who hopes to understand this topic. You understand a whole lot its almost tough to argue with you (not that I really would want to…HaHa). You certainly put a fresh spin on a topic which has been written about for many years. Excellent stuff, just wonderful!|

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found that it is really informative. I’m gonna watch out for brussels. I’ll be grateful if you continue this in future. Numerous people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!|

Its like you read my mind! You appear to know a lot about this, like you wrote the book in it or something. I think that you can do with a few pics to drive the message home a little bit, but instead of that, this is wonderful blog. A great read. I will certainly be back.|

You’re so awesome! I don’t think I have read through anything like that before. So wonderful to discover somebody with original thoughts on this topic. Seriously.. many thanks for starting this up. This website is something that is required on the internet, someone with a bit of originality!|

you are actually a good webmaster. The website loading pace is amazing. It seems that you’re doing any distinctive trick. Furthermore, The contents are masterpiece. you have performed a wonderful task on this matter!|

Greetings from Los angeles! I’m bored to tears at work so I decided to browse your site on my iphone during lunch break. I love the information you present here and can’t wait to take a look when I get home. I’m amazed at how fast your blog loaded on my cell phone .. I’m not even using WIFI, just 3G .. Anyhow, excellent blog!|

Hi my friend! I wish to say that this post is awesome, great written and come with almost all important infos. I would like to peer extra posts like this .|

Wonderful paintings! That is the kind of info that should be shared across the web. Disgrace on the seek engines for no longer positioning this submit higher! Come on over and consult with my website . Thank you =)

Way cool! Some very valid points! I appreciate you penning this article and the rest of the site is really good. OKBET

I like it when individuals come together and share ideas. Great blog, continue the good work! OKBET

It’s very simple to find out any topic on web as compared to textbooks, as I found this post at this website. OKBET

Hi, I do think this is an excellent site. I stumbledupon it 😉 I am going to return once again since i have bookmarked it. Money and freedom is the greatest way to change, may you be rich and continue to help others. OKBET Casino

It’s appropriate time to make some plans for the future and it’s time to be happy. I have read this post and if I could I wish to suggest you some interesting things or suggestions. Perhaps you can write next articles referring to this article. I want to read more things about it! OKBET

Wow, this piece of writing is good, my sister is analyzing such things, so I am going to convey her. OKBET

This is a topic that is close to my heart… Take care! Exactly where are your contact details though? OKBET

I have been browsing online greater than 3 hours nowadays, yet I never found any fascinating article like yours. It is lovely worth sufficient for me. Personally, if all site owners and bloggers made good content material as you did, the net can be a lot more helpful than ever before. OKBET

These are genuinely wonderful ideas in about blogging. You have touched some nice points here. Any way keep up wrinting. OKBET Casino

Howdy just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The words in your article seem to be running off the screen in Firefox. I’m not sure if this is a formatting issue or something to do with browser compatibility but I thought I’d post to let you know. The design and style look great though! Hope you get the issue fixed soon. Kudos OKBET

Hi, I do think this is an excellent website. I stumbledupon it 😉 I am going to revisit yet again since i have saved as a favorite it. Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and continue to help others. OKBET Casino

Hello would you mind letting me know which webhost you’re utilizing? I’ve loaded your blog in 3 different browsers and I must say this blog loads a lot faster then most. Can you recommend a good internet hosting provider at a honest price? Kudos, I appreciate it! OKBET

Woah! I’m really digging the template/theme of this site. It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s very difficult to get that “perfect balance” between user friendliness and visual appeal. I must say you have done a excellent job with this. In addition, the blog loads extremely fast for me on Safari. Excellent Blog! OKBET Casino

Woah! I’m really digging the template/theme of this website. It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s tough to get that “perfect balance” between superb usability and appearance. I must say that you’ve done a great job with this. Also, the blog loads extremely fast for me on Chrome. Excellent Blog! OKBET Casino

Woah! I’m really digging the template/theme of this website. It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s difficult to get that “perfect balance” between usability and visual appearance. I must say you’ve done a superb job with this. Additionally, the blog loads super fast for me on Safari. Excellent Blog! OKBET Casino

Hey! Someone in my Facebook group shared this site with us so I came to look it over. I’m definitely loving the information. I’m bookmarking and will be tweeting this to my followers! Fantastic blog and excellent style and design. OKBET Casino

Ahaa, its pleasant conversation concerning this post here at this blog, I have read all that, so at this time me also commenting at this place. OKBET

I love what you guys tend to be up too. This sort of clever work and exposure! Keep up the good works guys I’ve incorporated you guys to blogroll. OKBET Casino

Saved as a favorite, I like your site! OKBET

It’s very straightforward to find out any topic on net as compared to textbooks, as I found this post at this website. OKBET

I could not refrain from commenting. Very well written! OKBET

Woah! I’m really enjoying the template/theme of this blog. It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s very hard to get that “perfect balance” between usability and visual appeal. I must say that you’ve done a awesome job with this. In addition, the blog loads super fast for me on Opera. Excellent Blog! OKBET Casino

Way cool! Some extremely valid points! I appreciate you writing this article and also the rest of the website is really good. OKBET

Does your blog have a contact page? I’m having a tough time locating it but, I’d like to shoot you an email. I’ve got some ideas for your blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great site and I look forward to seeing it expand over time. OKBET Casino

I will immediately grasp your rss as I can not in finding your email subscription hyperlink or newsletter service. Do you have any? Please permit me realize in order that I may just subscribe. Thanks. OKBET

bookmarked!!, I really like your site! OKBET

It is the best time to make some plans for the future and it’s time to be happy. I have read this post and if I could I wish to suggest you some interesting things or advice. Perhaps you can write next articles referring to this article. I desire to read even more things about it! OKBET

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It in fact was a amusement account it. Look advanced to far added agreeable from you! By the way, how can we communicate? OKBET

It’s the best time to make some plans for the longer term and it is time to be happy. I’ve read this put up and if I may just I want to suggest you some interesting things or advice. Maybe you can write next articles relating to this article. I want to read more things approximately it! OKBET

Hi, I do believe this is a great site. I stumbledupon it 😉 I will return yet again since I book-marked it. Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and continue to help others. OKBET Casino

Everyone loves what you guys tend to be up too. This sort of clever work and coverage! Keep up the great works guys I’ve incorporated you guys to my blogroll. OKBET Casino

I could not resist commenting. Perfectly written! OKBET

I like it when folks come together and share thoughts. Great blog, stick with it! OKBET

Hi, I do believe this is an excellent blog. I stumbledupon it 😉 I will come back once again since I book-marked it. Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and continue to help other people. OKBET Casino

Everyone loves what you guys are up too. This sort of clever work and reporting! Keep up the amazing works guys I’ve added you guys to my blogroll. OKBET Casino

Howdy just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The text in your article seem to be running off the screen in Opera. I’m not sure if this is a formatting issue or something to do with internet browser compatibility but I thought I’d post to let you know. The layout look great though! Hope you get the issue fixed soon. Kudos OKBET

I enjoy what you guys are up too. This sort of clever work and reporting! Keep up the wonderful works guys I’ve incorporated you guys to blogroll. OKBET Casino

Does your blog have a contact page? I’m having a tough time locating it but, I’d like to shoot you an e-mail. I’ve got some ideas for your blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great site and I look forward to seeing it grow over time. OKBET Casino

Does your website have a contact page? I’m having problems locating it but, I’d like to shoot you an e-mail. I’ve got some recommendations for your blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great blog and I look forward to seeing it grow over time. OKBET Casino

Way cool! Some extremely valid points! I appreciate you penning this post plus the rest of the site is extremely good. OKBET

It’s perfect time to make a few plans for the long run and it’s time to be happy. I have learn this publish and if I may I desire to suggest you some interesting issues or tips. Maybe you can write next articles referring to this article. I wish to read even more issues approximately it! OKBET

Hey just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The words in your post seem to be running off the screen in Chrome. I’m not sure if this is a formatting issue or something to do with browser compatibility but I figured I’d post to let you know. The layout look great though! Hope you get the issue resolved soon. Thanks OKBET

Saved as a favorite, I really like your website! OKBET

It’s the best time to make some plans for the future and it’s time to be happy. I have read this post and if I could I desire to suggest you some interesting things or tips. Maybe you can write next articles referring to this article. I desire to read more things about it! OKBET

https://themesvillage.com/10-top-rated-news-wordpress-themes-for-2020/

certainly like your website however you need to test the spelling on several of your posts. Several of them are rife with spelling problems and I to find it very bothersome to inform the truth however I will definitely come back again.

Saved as a favorite, I like your web site! OKBET

Hello just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The text in your content seem to be running off the screen in Ie. I’m not sure if this is a format issue or something to do with web browser compatibility but I thought I’d post to let you know. The style and design look great though! Hope you get the problem fixed soon. Thanks OKBET

I am sure this piece of writing has touched all the internet people, its really really good piece of writing on building up new web site. OKBET

Everyone loves it whenever people come together and share thoughts. Great website, continue the good work! OKBET

I’ve been surfing on-line more than 3 hours nowadays, yet I never discovered any attention-grabbing article like yours. It’s lovely price enough for me. In my opinion, if all web owners and bloggers made just right content as you probably did, the net will likely be a lot more helpful than ever before. OKBET

I really like it when people get together and share views. Great site, keep it up! OKBET

It’s the best time to make some plans for the longer term and it is time to be happy. I have learn this post and if I may I want to suggest you few attention-grabbing issues or advice. Perhaps you can write next articles referring to this article. I desire to read even more things approximately it! OKBET

I like what you guys are usually up too. This sort of clever work and exposure! Keep up the wonderful works guys I’ve you guys to my blogroll. OKBET Casino

I have been browsing online more than 2 hours today, yet I never found any interesting article like yours. It is pretty worth enough for me. In my view, if all site owners and bloggers made good content as you did, the internet will be much more useful than ever before. OKBET

I am sure this post has touched all the internet people, its really really good post on building up new blog. OKBET

Hi, I do think this is a great website. I stumbledupon it 😉 I may return yet again since I bookmarked it. Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and continue to help other people. OKBET Casino

Does your blog have a contact page? I’m having a tough time locating it but, I’d like to send you an email. I’ve got some recommendations for your blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great blog and I look forward to seeing it develop over time. OKBET Casino

Hey there just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The words in your content seem to be running off the screen in Chrome. I’m not sure if this is a format issue or something to do with internet browser compatibility but I figured I’d post to let you know. The design look great though! Hope you get the issue solved soon. Cheers OKBET

Does your website have a contact page? I’m having a tough time locating it but, I’d like to shoot you an email. I’ve got some ideas for your blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great site and I look forward to seeing it improve over time.OKBET Sports

I’ll immediately clutch your rss as I can not to find your email subscription hyperlink or e-newsletter service. Do you have any? Kindly permit me recognise so that I may subscribe. Thanks.OKBET

I have been browsing online more than 3 hours today, yet I never found any interesting article like yours. It is pretty worth enough for me. Personally, if all webmasters and bloggers made good content as you did, the net will be much more useful than ever before.OKBET

Its like you learn my mind! You appear to grasp a lot about this, like you wrote the ebook in it or something. I think that you simply could do with some percent to power the message home a little bit, but instead of that, this is wonderful blog. A fantastic read. I will definitely be back. OKBET Casino

It is appropriate time to make some plans for the future and it is time to be happy. I’ve read this post and if I could I wish to suggest you some interesting things or advice. Perhaps you could write next articles referring to this article. I wish to read even more things about it!OKBET

Ahaa, its fastidious conversation on the topic of this piece of writing at this place at this website, I have read all that, so now me also commenting at this place.OKBET

Hi would you mind letting me know which web host you’re using? I’ve loaded your blog in 3 completely different web browsers and I must say this blog loads a lot quicker then most. Can you suggest a good hosting provider at a fair price? Thanks a lot, I appreciate it!OKBET

Hello there, just became alert to your blog through Google, and found that it is truly informative. I am gonna watch out for brussels. I?ll be grateful if you continue this in future. A lot of people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

Статья содержит информацию, подкрепленную надежными источниками, представленную без предвзятости.

Would you please share which blogging platform you use? I’m planning to start my own blog in the near future but I’m having a difficult time making a decision between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal. Your design and style seem different from most blogs, and I’m searching for something unique. P.S. Sorry to be off-topic, but I just had to ask.

Would you please share which blogging platform you use? I’m planning to start my own blog in the near future but I’m having a difficult time making a decision between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal. Your design and style seem different from most blogs, and I’m searching for something unique. P.S. Sorry to be off-topic, but I just had to ask.

Would you please share which blogging platform you use? I’m planning to start my own blog in the near future but I’m having a difficult time making a decision between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal. Your design and style seem different from most blogs, and I’m searching for something unique. P.S. Sorry to be off-topic, but I just had to ask.

Great post. I used to be checking continuously this blog and I’m inspired! Very helpful info specifically the closing phase 🙂 I care for such information much. I was seeking this particular info for a very lengthy time. Thanks and good luck.

Hello.This post was extremely motivating, particularly since I was looking for thoughts on this issue last Tuesday.

Thanks for the concepts you are revealing on this web site. Another thing I’d really like to say is that getting hold of duplicates of your credit profile in order to examine accuracy of each and every detail will be the first activity you have to conduct in repairing credit. You are looking to clear your credit report from destructive details errors that wreck your credit score.

hi!,I like your writing very much! share we communicate more about your article on AOL? I require an expert on this area to solve my problem. Maybe that’s you! Looking forward to see you.

When I originally left a comment I appear to have clicked on the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a comment is added I receive four emails with the exact same comment. Perhaps there is a way you are able to remove me from that service? Thank you.

Valuable info. Lucky me I found your web site by accident, and I am shocked why this accident did not happened earlier! I bookmarked it.

Hey There. I found your blog using msn. This is a very well written article. I?ll make sure to bookmark it and return to read more of your useful info. Thanks for the post. I?ll definitely comeback.

Я чувствую, что эта статья является настоящим источником вдохновения. Она предлагает новые идеи и вызывает желание узнать больше. Большое спасибо автору за его творческий и информативный подход!

I found this article to be incredibly well-researched and thoughtfully written. It presents a balanced view of the topic and offers practical advice. I appreciate the effort that went into creating such a comprehensive resource.

One other thing I would like to convey is that rather than trying to accommodate all your online degree tutorials on days and nights that you finish off work (because most people are fatigued when they return home), try to arrange most of your instructional classes on the week-ends and only one or two courses for weekdays, even if it means taking some time off your end of the week. This is fantastic because on the weekends, you will be extra rested along with concentrated on school work. Thanks alot : ) for the different recommendations I have learned from your site.

Статья содержит практические советы, которые можно применить в реальной жизни.

Автор старается сохранить нейтральность, чтобы читатели могли основываться на объективной информации при формировании своего мнения. Это сообщение отправлено с сайта https://ru.gototop.ee/

Я оцениваю широкий охват темы в статье.

Yesterday, while I was at work, my cousin stole my iPad and tested to see if it can survive a 30 foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My iPad is now destroyed and she has 83 views. I know this is completely off topic but I had to share it with someone!

Автор представляет разнообразные точки зрения на проблему, что помогает читателю получить обширное представление о ней.

After checking out a number of the articles on your web page, I truly appreciate your technique of writing a blog. I book marked it to my bookmark site list and will be checking back soon. Please check out my website as well and tell me how you feel.

Generally I don’t read post on blogs, but I wish to say that this write-up very forced me to try and do so! Your writing style has been amazed me. Thanks, very nice post.

Hey would you mind sharing which blog platform you’re using? I’m going to start my own blog soon but I’m having a tough time making a decision between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal. The reason I ask is because your layout seems different then most blogs and I’m looking for something completely unique. P.S My apologies for getting off-topic but I had to ask!

Great blog right here! Additionally your site so much up fast! What host are you using? Can I am getting your affiliate link for your host? I want my web site loaded up as fast as yours lol

What’s up, yup this article is genuinely nice and I have learned lot of things from it concerning blogging.

thanks.

That is a really good tip especially to those new to the blogosphere. Brief but very accurate information… Many thanks for sharing this one. A must read post!

Your style is so unique compared to many other people. Thank you for publishing when you have the opportunity,Guess I will just make this bookmarked.2

Hello there! This article couldn’t be written much better!

Looking through this article reminds me of my previous roommate!

He continually kept preaching about this. I’ll send this post to him.

Pretty sure he’ll have a very good read. Thank you for sharing!

of course like your web site however you have to check the spelling on quite a few of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling problems and I to find it very bothersome to inform the reality nevertheless I will certainly come back again.

I carry on listening to the news talk about receiving boundless online grant applications so I have been looking around for the finest site to get one. Could you tell me please, where could i find some?

Hello.This post was really remarkable, particularly because I was looking for thoughts on this topic last Wednesday.

Hello.This article was extremely interesting, particularly because I was investigating for thoughts on this subject last couple of days.

I wanted to thank you for this great read!! I definitely enjoying every little bit of it I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you post…

I have been absent for some time, but now I remember why I used to love this website. Thank you, I’ll try and check back more often. How frequently you update your website?

F*ckin’ tremendous things here. I’m very glad to see your post. Thanks so much and i am looking ahead to contact you. Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?

Good blog! I really love how it is simple on my eyes and the data are well written. I am wondering how I might be notified when a new post has been made. I’ve subscribed to your feed which must do the trick! Have a nice day!

Hello there! I know this is kind of off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could find a captcha plugin for my comment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having problems finding one? Thanks a lot!

Definitely believe that which you said. Your favorite reason seemed to be on the internet the simplest thing to be aware of. I say to you, I certainly get annoyed while people think about worries that they plainly do not know about. You managed to hit the nail upon the top and also defined out the whole thing without having side-effects , people can take a signal. Will likely be back to get more. Thanks

Wow, incredible blog layout! How lengthy have you been blogging for? you make blogging glance easy. The overall glance of your website is magnificent, let alone the content material!

Thanks for this insightful information. It really helped me understand the topic better. Nice!

This info is priceless. How can I find out more?

I am often to blogging and i really appreciate your content. The article has really peaks my interest. I am going to bookmark your site and keep checking for new information.

Thanks , I’ve recently been searching for info about this subject for ages and yours is the greatest I’ve discovered so far. But, what about the bottom line? Are you sure about the source?

Your style is so unique compared to many other people. Thank you for publishing when you have the opportunity,Guess I will just make this bookmarked.2

This web site definitely has all of the info I wanted about this subject and didn’t know who to ask.

Hi there very nice site!! Man .. Beautiful .. Amazing .. I’ll bookmark your blog and take the feeds also…I am happy to seek out a lot of helpful info here in the publish, we’d like work out extra strategies in this regard, thank you for sharing. . . . . .

Sweet blog! I found it while browsing on Yahoo News. Do you have any tips on how to get listed in Yahoo News? I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get there! Appreciate it

It’s the best time to make some plans for the future and it’s time to be happy. I have read this post and if I could I wish to suggest you few interesting things or advice. Maybe you can write next articles referring to this article. I desire to read more things about it!

I will right away grab your rss feed as I can not find your e-mail subscription link or e-newsletter service. Do you have any? Please let me know so that I could subscribe. Thanks.

F*ckin’ amazing things here. I’m very glad to peer your post. Thanks a lot and i’m taking a look ahead to touch you. Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?

Attractive section of content. I just stumbled upon your web site and in accession capital to assert that I get actually enjoyed account your blog posts. Anyway I’ll be subscribing to your feeds and even I achievement you access consistently rapidly.

Usually I don’t read post on blogs, but I would like to say that this write-up very forced me to try and do it! Your writing style has been amazed me. Thanks, very nice post.

This text is invaluable. When can I find out more?

I really glad to find this internet site on bing, just what I was looking for : D besides saved to fav.

An interesting discussion is worth comment. I think that you should write more on this topic, it might not be a taboo subject but generally people are not enough to speak on such topics. To the next. Cheers

The subsequent time I learn a weblog, I hope that it doesnt disappoint me as much as this one. I mean, I do know it was my option to learn, but I actually thought youd have something attention-grabbing to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about something that you can repair when you werent too busy searching for attention.

Great blog! Do you have any recommendations for aspiring writers?

I’m planning to start my own site soon but I’m a little lost on everything.

Would you recommend starting with a free platform like WordPress

or go for a paid option? There are so many options out

there that I’m completely overwhelmed .. Any ideas?

Cheers!

bookmarked!!, I really like your web site.

Thanks a lot for sharing this with all of us you really know what you are talking about! Bookmarked. Kindly also visit my site =). We could have a link exchange agreement between us!

Hey there! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a group of volunteers and starting a

new project in a community in the same niche. Your blog

provided us valuable information to work on. You have done a extraordinary job!

Enjoyed reading through this, very good stuff, thankyou.

Greetings I am so excited I found your webpage, I really found you by error, while I was searching on Yahoo for something else, Anyways I am here now and would just like to say kudos for a marvelous post and a all round thrilling blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to read it all at the minute but I have saved it and also added in your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read a great deal more, Please do keep up the excellent job.

Hmm it seems like your site ate my first comment (it was super long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I had written and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I as well am an aspiring blog blogger but I’m still new to the whole thing. Do you have any helpful hints for inexperienced blog writers? I’d really appreciate it.

delta 8 arkansas 2021

It is really a great and useful piece of information. I am glad that you shared this useful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

Definitely, what a splendid website and educative posts, I definitely will bookmark your website.Have an awsome day!

It’s a pity you don’t have a donate button! I’d definitely donate to this outstanding blog! I guess for now i’ll settle for bookmarking and adding your RSS feed to my Google account. I look forward to new updates and will share this blog with my Facebook group. Chat soon!

Thanks for the strategies you have provided here. Moreover, I believe there are many factors which really keep your auto insurance premium all the way down. One is, to bear in mind buying cars that are from the good report on car insurance providers. Cars which have been expensive are more at risk of being snatched. Aside from that insurance coverage is also using the value of your truck, so the costlier it is, then higher the actual premium you have to pay.

Hi my friend! I wish to say that this post is amazing, nice written and include approximately all important infos. I would like to see more posts like this.

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!

Thanks for another informative blog. Where else could I get that type of info written in such an ideal way? I’ve a project that I am just now working on, and I’ve been on the look out for such information.

I really appreciate this post. I’ve been looking everywhere for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You’ve made my day! Thx again

I just added this blog to my google reader, excellent stuff. Can not get enough!

I have read a few just right stuff here. Definitely price bookmarking for revisiting. I surprise how much effort you set to create any such magnificent informative site.

Hi would you mind letting me know which web host you’re utilizing? I’ve loaded your blog in 3 different browsers and I must say this blog loads a lot quicker then most. Can you suggest a good web hosting provider at a fair price? Kudos, I appreciate it!

Thanks, I have just been looking for info approximately this subject for a long time and yours is the best I’ve came upon so far. But, what about the bottom line? Are you positive about the supply?

Sweet internet site, super design and style, very clean and utilise genial.

Some genuinely nice stuff on this internet site, I enjoy it.

The next time I learn a weblog, I hope that it doesnt disappoint me as a lot as this one. I mean, I do know it was my choice to read, however I truly thought youd have something interesting to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about one thing that you can repair when you werent too busy in search of attention.

After I originally commented I clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get 4 emails with the identical comment. Is there any approach you may remove me from that service? Thanks!

We’re a group of volunteers and opening a brand new scheme in our community.

Your website offered us with helpful information to work on. You have

performed an impressive job and our whole community can be grateful to you.

Lovely just what I was searching for.Thanks to the author for taking his time on this one.

Good day I am so happy I found your site, I really found you by accident, while I was looking on Aol for something else, Anyways I am here now and would just like to say thanks for a incredible post and a all round entertaining blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to look over it all at the moment but I have saved it and also added in your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read much more, Please do keep up the superb job.

Sweet web site, super style and design, real clean and employ friendly.

Please let me know if you’re looking for a author for your blog. You have some really great posts and I feel I would be a good asset. If you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d love to write some material for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine. Please blast me an e-mail if interested. Cheers!

I haven’t checked in here for a while as I thought it was getting boring, but the last few posts are good quality so I guess I’ll add you back to my daily bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

I’d have to check with you here. Which isn’t something I normally do! I take pleasure in reading a post that will make people think. Also, thanks for allowing me to remark!

I have recently started a website, the info you provide on this site has helped me tremendously. Thanks for all of your time & work.

I can’t express how much I admire the effort the author has put into writing this remarkable piece of content. The clarity of the writing, the depth of analysis, and the abundance of information presented are simply remarkable. Her zeal for the subject is evident, and it has undoubtedly struck a chord with me. Thank you, author, for sharing your knowledge and enriching our lives with this extraordinary article!

Pretty! This was a really wonderful post. Thank you for your provided information.