[intro]Sharpeville is one of the oldest townships in Southern Gauteng’s Vaal Triangle. This weekend it is exactly 55 years since the name of this small place reverberated around the world.

On 21 March 1960 the police shot and killed 69 people because they stood up for their human rights. Tim Knight was working on a Johannesburg-based weekly newspaper at the time.The legendary Peter Magubane was a young courageous photographer who captured the funeral image that shocked the world.[/intro]

I’m a twenty-two year-old reporter on the Sunday Express, Johannesburg, when police slaughter sixty-nine unarmed black protesters at Sharpeville.

And South Africa changes forever.

Peter Magubane photo of Sharpeville funeral

The funeral for the Sharpeville sixty-nine is scheduled for a few days after the massacre. The paranoid apartheid government, of course, wants no public record of it.

So no reporters.

Police and soldiers cordon off the entire area with barbed wire, armoured cars and an iron curtain of guns.

But Sharpeville is a huge international story. The funeral must be covered.

ANC friends who know the area offer to smuggle Sunday Express chief photographer James Soullier and me by a back ravine through police lines.

We meet our guides very early on the morning. It’s close to noon by the time we get around the men with the uniforms and the guns and get to the funeral.

The picture haunts me to this day. A line of open graves cut out of the red clay stretches as far as I can see. Next to each grave lies an identical wooden coffin.

An enormous crowd of black mourners weeps, sings hymns, chants black power slogans.

James and I seem to be the only whites in this very black, very angry world.

We’re certainly the only white journalists.

Neither of us have any illusions about what can happen. The crowd has every reason to turn on us — take revenge for the sixty-nine Sharpeville murders and the sheer, bloody, racist brutality of this white-supremacist state.

No-one will ever know who slashes the first panga or smashes the last knobkerrie.

No-one will ever know. And anyway, in the long run it simply won’t matter.

But instead of violence, we’re welcomed as honoured guests and given an unofficial bodyguard — just in case. But no bodyguard is needed.

I interview people and James takes his pictures. No problem. No one even curses us.

And it’s possible that our story in the Sunday Express about the Sharpeville funeral helps — in its own, very small way — to eventually end the evil that was apartheid.

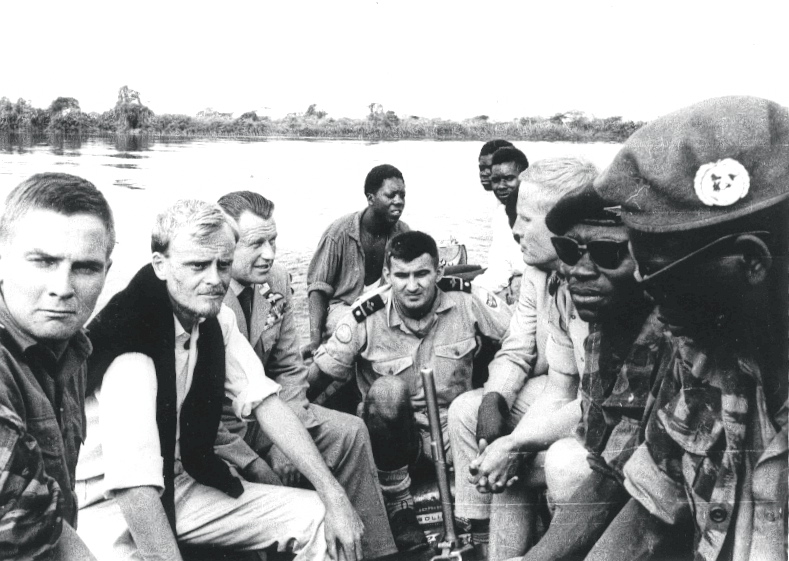

Tim Knight (second from left) was Foreign correspondent for UPI in 1964 when he joined a UN reconnaissance team seeking the rebel headquarters in the Congo. They were captured by Katangese rebels, beaten and interrogated for hours before being released.

It’s three years later on a hell-hot night in Elisabethville (now Lubumbashi), capital of the Congo’s breakaway province, Katanga.

I’m foreign correspondent for United Press International. Outside my apartment, United Nations and Congolese troops patrol the streets.

The last Congo war has ended and the next hasn’t started yet.

Occasional gunshots shatter the night. In this neighbourhood, we ignore shooting. Anyway, there’s nowhere to run to.

A Katangese friend arrives at my door with two very nervous, very tired white men. I recognise them immediately from newspaper photographs.

They’re the world’s two most famous wanted men — Arthur Goldreich and Harold Wolpe.

Until recently, they’re senior advisers with the banned ANC and its armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK).

They’re the men who secretly rent Liliesleaf, a farm near Johannesburg, as a base for MK strategy sessions. It’s Liliesleaf where Nelson Mandela poses as a farm labourer to hide from police while plotting to bring down the state.

When police raid the farm they capture nineteen top ANC leaders. Soon after, Wolpe is arrested too. He ends up in the notorious Marshall Square prison in Johannesburg. Goldreich is already there.

The two men are charged with treason and face possible death sentences. But instead of waiting for trial, they bribe their way out of Marshall Square and disappear.

The apartheid government is humiliated. It posts a huge reward for their capture. Wherever they are.

This night, every bounty hunter in the world wants to catch Godlreich and Wolpe, sell them back to the South African government, and collect the reward.

And every journalist in the world is looking for them, wants to write their story.

I invite them in. My wife Helen opens cold beers and we talk late into the evening.

We talk of Mandela who sits in jail facing a death sentence. We talk of the horrors of apartheid, of increasing South African police brutality.

Goldreich explains why the police massacre of sixty-nine unarmed protesters at Sharpeville is the final reason the ANC — frustrated that all lawful means of ending apartheid are exhausted — reluctantly picks up the gun.

And it’s Sharpeville that persuades him, a very respectable, wealthy white artist, to join Mandela and Umkhonto we Sizwe to fight violence with violence.

I mention shyly that I’m the only white reporter able to get through police lines to report on the Sharpeville funeral.

I recall how safe I feel among the crowd of angry, chanting, black mourners.

How protective and generous they are towards me, in spite of my colour.

How humble that makes me feel. And how deeply that generosity still affects me.

Neither Goldreich nor Wolpe are even slightly surprised. That’s how Africans treat guests.

When Goldreich and Wolpe are finally collected by the British consul around midnight, I feel honoured by the visit — if only for an accidental evening — by two extraordinarily brave and honourable men.

The whole world is looking for them. And here they are, sitting in my apartment in Elisabethville, drinking my beer.

Even so, I can’t write the story. Not until they’re out of Africa and safe from South African agents and the hungry legions of bounty hunters.

It’s nearly a week before Arthur Goldreich and Harold Wolpe surface safely in London.

By that time, sadly, my world scoop for United Press International is nothing more than an interesting footnote to The Struggle.

In the many years since all that happened, I’ve covered thousands of stories in a dozen countries.

But nothing can compare with that funeral fifty-five years ago — the single most significant, most important, event I’ve ever reported.

That’s because the Sharpeville massacre and funeral were the beginning of the end of a fascist, racist government.

And the start of a new non-racial, democratic South Africa.

Parts of this column are adapted from previous reports by Tim Knight on Sharpeville and the Congo wars.

Knight is a Cape Town-based Emmy and Sigma Delta Chi-winning journalist and communications coach. He’s author of Storytelling and the Anima Factor, now in its second edition, and can be reached at www.TimKnight.org.

Peter Magubane has won many awards in his lifetime including the Order for Meritorious Service Class II from President Nelson Mandela.

Thanks for your ideas. One thing really noticed is that banks as well as financial institutions really know the spending habits of consumers and as well understand that most of the people max out their credit cards around the vacations. They smartly take advantage of that fact and then start flooding your inbox along with snail-mail box using hundreds of no interest APR credit card offers just after the holiday season finishes. Knowing that should you be like 98 of all American community, you’ll soar at the opportunity to consolidate credit card debt and shift balances for 0 annual percentage rates credit cards.

I am not sure where you’re getting your info, but good topic. I needs to spend some time learning much more or understanding more. Thanks for fantastic info I was looking for this information for my mission.

I respect the logic in this essay, but I would like to see further work on this from you soon.

I’m not sure exactly why but this website is loading very slow for me. Is anyone else having this issue or is it a issue on my end? I’ll check back later on and see if the problem still exists.

Please tell me more about this. May I ask you a question?

Thank you for your articles. I find them very helpful. Could you help me with something?

Thanks for your help and for writing this post. It’s been great.

Your articles are extremely helpful to me. Please provide more information!

Can you write more about it? Your articles are always helpful to me. Thank you!

Thanks for posting. I really enjoyed reading it, especially because it addressed my problem. It helped me a lot and I hope it will help others too.

Thank you for your articles. I find them very helpful. Could you help me with something?

You’ve been great to me. Thank you!

Please tell me more about your excellent articles

Great information. Lucky me I came across your site by accident (stumbleupon). I’ve saved it for later!

hemplitude delta 8 gummies reddit

Wonderful advice! Have you ever thought if you’ve integrated your system with freenlacer.com?

I’m so in love with this. You did a great job!!

Whos is the author of this article?

whats the difference between delta 8 and thco

You detail some logical statements.

I’ve had success in connecting with local service providers through the classifieds section.

The option to share ads directly with friends and contacts via email or messaging is a convenient way to spread the word.

I like the valuable information you provide for your articles. I will bookmark your blog and take a look at once more here regularly. I’m reasonably sure I will be told many new stuff right here! Best of luck for the next!

Hey there, You’ve done a fantastic job. I抣l certainly digg it and for my part suggest to my friends. I’m sure they will be benefited from this website.

Hello there, just became alert to your blog through Google, and found that it is really informative. I am gonna watch out for brussels. I抣l appreciate if you continue this in future. Lots of people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

A powerful share, I simply given this onto a colleague who was doing a bit evaluation on this. And he in truth purchased me breakfast as a result of I found it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the treat! But yeah Thnkx for spending the time to debate this, I feel strongly about it and love studying more on this topic. If attainable, as you become experience, would you thoughts updating your blog with more details? It is extremely helpful for me. Big thumb up for this blog post!

You made some first rate points there. I regarded on the internet for the issue and found most people will go along with with your website.

Я хотел бы выразить свою благодарность автору за его глубокие исследования и ясное изложение. Он сумел объединить сложные концепции и представить их в доступной форме. Это действительно ценный ресурс для всех, кто интересуется этой темой.

Я бы хотел выразить свою благодарность автору этой статьи за его профессионализм и преданность точности. Он предоставил достоверные факты и аргументированные выводы, что делает эту статью надежным источником информации.

Автор не высказывает собственных предпочтений, что позволяет читателям самостоятельно сформировать свое мнение.

Статья представляет разнообразные аргументы и контекст, позволяя читателям самостоятельно сформировать свое мнение.

Статья представляет обобщенный взгляд на проблему, учитывая ее многогранные аспекты.

Автор предлагает практические рекомендации, которые могут быть полезны в реальной жизни.

Очень хорошо структурированная статья! Я оцениваю ясность и последовательность изложения. Благодаря этому, я смог легко следовать за логикой и усвоить представленную информацию. Большое спасибо автору за такой удобный формат!

The author provides alternative solutions to the problems discussed.

Статья содержит сбалансированный подход к теме и учитывает различные точки зрения.

Очень хорошо организованная статья! Автор умело структурировал информацию, что помогло мне легко следовать за ней. Я ценю его усилия в создании такого четкого и информативного материала.

Очень понятная и информативная статья! Автор сумел объяснить сложные понятия простым и доступным языком, что помогло мне лучше усвоить материал. Огромное спасибо за такое ясное изложение!

Мне понравилось разнообразие информации в статье, которое позволяет рассмотреть проблему с разных сторон.

Удобно, что многие доски объявлений предлагают возможность фильтрации результатов по расстоянию или ценовому диапазону.

Вместо этого, вы можете указать произвольный адрес электронной почты., и отправитель будет указан как “CandyMail.org”.

CandyMail.org is an innovative platform that provides users with a secure and anonymous way to send and receive electronic mail. With the increasing concern over online privacy and data security, CandyMail.org has emerged as a reliable solution for individuals seeking confidentiality in their email communications. In this article, we will explore the unique features and benefits of CandyMail.org, as well as its impact on protecting user privacy.

Читателям предоставляется возможность самостоятельно изучить представленные факты и сделать информированный вывод.

Я не могу не отметить качество исследования, представленного в этой статье. Автор использовал надежные источники и предоставил нам актуальную информацию. Большое спасибо за такой надежный и информативный материал!

The author provides a balanced overview of the current state of research.

The article offers practical recommendations based on the findings.

Надеюсь, эти комментарии добавят вашу положительную отзывчивость к информационной статье!

The information in this article is presented in a manner that promotes understanding.

Автор статьи предоставляет различные точки зрения и экспертные мнения, не принимая сторону.

Статья является исчерпывающим и объективным рассмотрением темы.

Я оцениваю фактическую базу, представленную в статье.

Я не могу не отметить стиль и ясность изложения в этой статье. Автор использовал простой и понятный язык, что помогло мне легко усвоить материал. Огромное спасибо за такой доступный подход!

Это способствует более глубокому пониманию темы и формированию информированного мнения.

Автор хорошо подготовился к теме и представил разнообразные факты.

Статья представляет объективную оценку проблемы, учитывая мнение разных экспертов и специалистов.

Мне понравился объективный подход автора, который не пытается убедить читателя в своей точке зрения.

Автор старается представить материал нейтрально, оставляя пространство для собственного рассмотрения и анализа.

Хорошая статья, в которой автор предлагает различные точки зрения и аргументы.

Я хотел бы выразить свою благодарность автору за его глубокие исследования и ясное изложение. Он сумел объединить сложные концепции и представить их в доступной форме. Это действительно ценный ресурс для всех, кто интересуется этой темой.

Автор предлагает практические рекомендации, которые могут быть полезны в реальной жизни.

Автор приводит разные аргументы и факты, позволяя читателям сделать собственные выводы.

Мне понравилась объективность автора и его способность представить информацию без предвзятости.

Я просто восхищен этой статьей! Автор предоставил глубокий анализ темы и подкрепил его примерами и исследованиями. Это помогло мне лучше понять предмет и расширить свои знания. Браво!

Читателям предоставляется возможность рассмотреть разные аспекты темы и сделать собственные выводы на основе предоставленных данных. Это сообщение отправлено с сайта https://ru.gototop.ee/

Автор статьи представляет различные точки зрения на тему, предоставляя аргументы и контекст.

Очень интересная исследовательская работа! Статья содержит актуальные факты, аргументированные доказательствами. Это отличный источник информации для всех, кто хочет поглубже изучить данную тему.

Очень понятная и информативная статья! Автор сумел объяснить сложные понятия простым и доступным языком, что помогло мне лучше усвоить материал. Огромное спасибо за такое ясное изложение! Это сообщение отправлено с сайта https://ru.gototop.ee/

Автор старается не вмешиваться в оценку информации, чтобы читатели могли сами проанализировать и сделать выводы.

Статья содержит актуальную информацию по данной теме.

Статья предоставляет объективную информацию о теме, подкрепленную различными источниками.

Автор статьи представляет факты и события с акцентом на нейтральность.

Автор предлагает логические выводы на основе представленных фактов и аргументов.

Do you have any video of that? I’d want to find out some additional information.

I visited several blogs however the audio feature for audio songs present at this site is truly marvelous.

I’m really enjoying the design and layout

of your site. It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more pleasant for me

to come here and visit more often. Did you hire out a developer to create your theme?

Fantastic work!

Wow that was odd. I just wrote an extremely long comment

but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear. Grrrr…

well I’m not writing all that over again. Anyhow, just wanted to say

fantastic blog!

You really make it appear really easy together with your presentation however I to find this topic to be really something that I feel

I’d by no means understand. It sort of feels too complicated and

extremely broad for me. I am taking a look forward to your next publish, I will try to

get the hang of it!

I am now not sure the place you’re getting your info, but great topic.

I needs to spend some time finding out much more or understanding

more. Thanks for great information I used to be

in search of this information for my mission.

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It if truth be told was a amusement

account it. Look complex to more introduced agreeable from you!

However, how can we communicate?

Hi my friend! I want to say that this article is amazing, nice written and include almost all

significant infos. I would like to peer extra posts

like this .

I’ve been surfing on-line more than three hours lately, yet I by no means discovered any attention-grabbing article like yours.

It is beautiful value sufficient for me. Personally, if all webmasters

and bloggers made good content as you did, the web will be a lot more useful than ever before.

My partner and I stumbled over here from a different web page and

thought I may as well check things out. I like what I see so i am

just following you. Look forward to looking over your web page for a second time.

Every weekend i used to pay a visit this web site, because i

wish for enjoyment, as this this site conations actually nice funny stuff too.

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found that it is really informative.

I am gonna watch out for brussels. I’ll be grateful if you continue this in future.

Numerous people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

What you published was actually very reasonable.

However, what about this? suppose you added a

little content? I mean, I don’t want to tell you how to run your website, but what if

you added a title that grabbed folk’s attention? I

mean Sharpeville 1960: A Journalist Remembers

| The Journalist is kinda boring. You ought to peek at Yahoo’s front page and

see how they create post headlines to grab people to open the links.

You might try adding a video or a related pic or two to grab people interested

about what you’ve got to say. Just my opinion, it could make your posts a little livelier.

Hi, I check your new stuff daily. Your story-telling

style is awesome, keep doing what you’re doing!

Suspicious deaths of Russian businesspeople (2022–2023) – Wikipedia https://linkdirectory.at/detail/suspicious-deaths-of-russian-businesspeople-2022-2023-wikipedia

What’s up i am kavin, its my first time to commenting anyplace, when i

read this post i thought i could also make comment due to this good piece of writing.

Hello, just wanted to tell you, I liked this article. It was funny.

Keep on posting!

If you would like to improve your knowledge only keep visiting this

site and be updated with the most recent information posted here.

I do agree with all the concepts you’ve introduced on your

post. They are very convincing and will definitely work.

Still, the posts are too short for novices. Could you please prolong them a little from subsequent time?

Thank you for the post.

A list of public SLPDB instances for Bitcoin Cash SLP – https://wiki.electroncash.de/wiki/List_of_public_SLPDB_instances

We’re a bunch of volunteers and starting a brand new scheme

in our community. Your website provided us with useful information to

work on. You have done a formidable process and our

entire community shall be grateful to you.

Nice blog here! Also your web site loads up very fast!

What host are you using? Can I get your affiliate hyperlink for your host?

I desire my site loaded up as fast as yours

lol

Great blog here! Also your web site lots up fast! What web host are you the use of?

Can I get your associate hyperlink on your host? I desire my site loaded

up as quickly as yours lol

Attractive section of content. I just stumbled upon your blog and in accession capital to assert that I acquire actually enjoyed account your

blog posts. Anyway I will be subscribing to your feeds and even I

achievement you access consistently quickly.

Awesome post.

I am truly thankful to the owner of this web page who has shared this fantastic post at at this time.

Miss B Nasty, Ivy The Character, Im xXx Dark Only Fans Leaks Mega Folder Link ( https://picturesporno.com )

Mulan Hernandez, Puerto Rican Dime Only Fans Mega Link Leaks( https://PicturesPorno.com )

Alexis Skyy Nudes Only Fans Leaks( https://picturesporno.com )

Hi! Would you mind if I share your blog with my twitter group? There’s a lot of people that I think would really appreciate your content. Please let me know. Thanks

This is a topic which is near to my heart… Best wishes! Exactly where are your contact details though?

Thank you for another informative blog. Where else could I get that kind of info written in such an ideal way? I have a project that I am just now working on, and I’ve been on the look out for such info.

Awesome Site, Stick to the excellent work. thnx. [url=http://www.ww.ww.concerthouse.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=204627]lamisil bez recepty medycznej w Wrocławiu[/url]

Статья содержит полезные факты и аргументы, которые помогают разобраться в сложной теме.

Я оцениваю объективность автора и его стремление представить разные точки зрения на проблему.

Discuss the importance of environmental values and how they shape attitudes toward sustainability, conservation, and ecological responsibility.

Download Exactly E Nude Only Fans Leaks – https://Leaks.Zone/Emonneeyy_Mega

I抳e recently started a web site, the info you offer on this site has helped me greatly. Thank you for all of your time & work.

Excellent blog here! Also your web site loads up very fast! What web host are you using? Can I get your affiliate link to your host? I wish my website loaded up as quickly as yours lol

When I initially commented I clicked the “Notify me when new comments are added” checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get several e-mails with the same comment. Is there any way you can remove people from that service? Many thanks!

Наша бригада квалифицированных мастеров подготовлена предлагать вам современные средства, которые не только обеспечивают надежную безопасность от прохлады, но и подарят вашему зданию стильный вид.

Мы функционируем с новейшими строительными материалами, обеспечивая долгосрочный запас службы и прекрасные эффекты. Изолирование внешнего слоя – это не только экономия тепла на обогреве, но и трепет о окружающей природе. Экологичные технологические решения, какие мы производим, способствуют не только личному, но и сохранению природных богатств.

Самое основополагающее: [url=https://ppu-prof.ru/]Утепление дома цена за квадратный[/url] у нас составляет всего от 1250 рублей за квадратный метр! Это доступное решение, которое изменит ваш дом в подлинный тепловой угол с минимальными издержками.

Наши произведения – это не единственно изолирование, это формирование помещения, в где всякий элемент отразит ваш собственный образ действия. Мы возьмем во внимание все ваши пожелания, чтобы преобразить ваш дом еще более удобным и привлекательным.

Подробнее на [url=https://ppu-prof.ru/]http://ppu-prof.ru/[/url]

Не откладывайте занятия о своем корпусе на потом! Обращайтесь к мастерам, и мы сделаем ваш жилище не только более теплым, но и модернизированным. Заинтересовались? Подробнее о наших проектах вы можете узнать на интернет-портале. Добро пожаловать в мир благополучия и высоких стандартов.

Your place is valueble for me. Thanks!?

CBD exceeded my expectations in every way thanks. I’ve struggled with insomnia looking for years, and after infuriating CBD like https://www.cornbreadhemp.com/products/cbd-sleep-gummies for the first once upon a time, I finally trained a loaded evening of calm sleep. It was like a weight had been lifted mad my shoulders. The calming effects were calm despite it sage, allowing me to drift afar obviously without sensibilities woozy the next morning. I also noticed a reduction in my daytime apprehension, which was an unexpected but allowed bonus. The cultivation was a bit rough, but nothing intolerable. Comprehensive, CBD has been a game-changer inasmuch as my siesta and anxiety issues, and I’m appreciative to have discovered its benefits.

Mood changes can include euphoria and extreme depression and may blonde cam girls the way

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on meta_keyword. Regards

Информационная статья представляет различные аргументы и контекст в отношении обсуждаемой темы.

Я восхищен этой статьей! Она не только предоставляет информацию, но и вызывает у меня эмоциональный отклик. Автор умело передал свою страсть и вдохновение, что делает эту статью поистине превосходной.

Автор статьи предоставляет информацию, подкрепленную надежными источниками, что делает ее достоверной и нейтральной.

Надеюсь, вам понравятся и эти комментарии!

I’m truly impressed by your deep insights and stellar writing style. The knowledge you share is evident in every piece you write. It’s obvious that you invest a great deal of effort into researching your topics, and this effort is well-appreciated. Thanks for providing such valuable insights. Continue the excellent job! https://www.elevenviral.com

Надеюсь, вам понравятся и эти комментарии! Это сообщение отправлено с сайта GoToTop.ee

Это позволяет читателям самостоятельно оценить и проанализировать информацию.

Автор статьи представляет факты и события с акцентом на нейтральность.

Читателям предоставляется возможность самостоятельно рассмотреть и проанализировать информацию.

Great article.

Автор статьи предоставляет информацию в понятной форме, избегая субъективных оценок.

Hi there, this weekend is nice in favor of me, for the reason that this point in time i am reading this enormous educational paragraph here at my house.

Автор умело структурирует информацию, что помогает сохранить интерес читателя на протяжении всей статьи.

Я бы хотел отметить актуальность и релевантность этой статьи. Автор предоставил нам свежую и интересную информацию, которая помогает понять современные тенденции и развитие в данной области. Большое спасибо за такой информативный материал!

Howdy are using WordPress for your blog platform? I’m new to the blog world but I’m trying to get started and create my own. Do you need any coding expertise to make your own blog? Any help would be really appreciated!

Автор статьи представляет информацию, подкрепленную различными источниками, что способствует достоверности представленных фактов. Это сообщение отправлено с сайта https://ru.gototop.ee/

Heya exceptional website! Does running a blog similar to this take a great deal of work? I have absolutely no knowledge of coding but I had been hoping to start my own blog soon. Anyways, should you have any ideas or techniques for new blog owners please share. I know this is off subject nevertheless I just needed to ask. Appreciate it!

Автор приводит примеры из различных источников, что позволяет получить более полное представление о теме. Статья является нейтральным и информативным ресурсом для тех, кто интересуется данной проблематикой.

Hi to all, how is the whole thing, I think every one is getting more from this web site, and your views are good in support of new users.

Автор предоставляет анализ последствий проблемы и возможных путей ее решения.

Я оцениваю объективность и сбалансированность подхода автора к представлению информации.

Автор предлагает разнообразные точки зрения на проблему, что помогает читателю получить обширное понимание ситуации.

Автор предлагает читателю дополнительные материалы для глубокого изучения темы.

Эта статья является настоящим источником вдохновения и мотивации. Она не только предоставляет информацию, но и стимулирует к дальнейшему изучению темы. Большое спасибо автору за его старания в создании такого мотивирующего контента!

Статья предлагает глубокий анализ темы и рассматривает ее со всех сторон.

Автор статьи предоставляет информацию, подкрепленную исследованиями и доказательствами, без выражения личных предпочтений. Это сообщение отправлено с сайта https://ru.gototop.ee/

I just like the valuable info you supply in your articles. I will bookmark your weblog and test once more right here frequently. I am slightly sure I’ll be informed many new stuff right here! Best of luck for the following!

Hi to all, how is all, I think every one is getting more from this website, and your views are fastidious for new people.

Автор предлагает систематический анализ проблемы, учитывая разные точки зрения.

Статья хорошо структурирована, что облегчает чтение и понимание.

Эта статья – настоящий кладезь информации! Я оцениваю ее полноту и разнообразие представленных фактов. Автор сделал тщательное исследование и предоставил нам ценный ресурс для изучения темы. Большое спасибо за такое ценное содержание!

Спасибо за эту статью! Она превзошла мои ожидания. Информация была представлена кратко и ясно, и я оставил эту статью с более глубоким пониманием темы. Отличная работа!

Надеюсь, что эти комментарии добавят ещё больше позитива и поддержки к информационной статье! Это сообщение отправлено с сайта GoToTop.ee

Это помогает читателям получить полное представление о сложности и многообразии данного вопроса.

Статья помогает читателю разобраться в сложной проблеме, предлагая разные подходы к ее решению.

Hi, I do think this is an excellent site. I stumbledupon it 😉 I may revisit once again since i have book marked it. Money and freedom is the greatest way to change, may you be rich and continue to help others.

Спасибо за эту статью! Она превзошла мои ожидания. Информация была представлена кратко и ясно, и я оставил эту статью с более глубоким пониманием темы. Отличная работа!

Howdy! Would you mind if I share your blog with my twitter group? There’s a lot of folks that I think would really enjoy your content. Please let me know. Many thanks

Я оцениваю объективность автора и его способность представить информацию без предвзятости и смещений.

Хорошая статья, в которой автор предлагает различные точки зрения и аргументы.

Very good info. Lucky me I discovered your site by accident (stumbleupon). I’ve saved it for later!

I have to thank you for the efforts you’ve put in penning this site. I am hoping to check out the same high-grade content by you later on as well. In fact, your creative writing abilities has motivated me to get my own, personal site now 😉

Статья содержит актуальную статистику, что помогает более точно оценить ситуацию.

Автор статьи хорошо структурировал информацию и представил ее в понятной форме.

Greate pieces. Keep posting such kind of info on your page. Im really impressed by it.

I’m extremely inspired together with your writing skills and also with the format in your weblog. Is that this a paid theme or did you modify it yourself? Anyway keep up the nice quality writing, it’s rare to look a nice weblog like this one these days..

Автор умело структурирует информацию, что помогает сохранить интерес читателя на протяжении всей статьи.

Автор предлагает дополнительные ресурсы, которые помогут читателю углубиться в тему и расширить свои знания.

Я бы хотел выразить свою благодарность автору этой статьи за его профессионализм и преданность точности. Он предоставил достоверные факты и аргументированные выводы, что делает эту статью надежным источником информации.

Автор представил широкий спектр мнений на эту проблему, что позволяет читателям самостоятельно сформировать свое собственное мнение. Полезное чтение для тех, кто интересуется данной темой.

Это помогает читателям самостоятельно разобраться в сложной теме и сформировать собственное мнение.

Статья помогла мне лучше понять сложные концепции, связанные с темой.

Отличная статья! Я бы хотел отметить ясность и логичность, с которыми автор представил информацию. Это помогло мне легко понять сложные концепции. Большое спасибо за столь прекрасную работу!

Эта статья оказалась исключительно информативной и понятной. Автор представил сложные концепции и теории в простой и доступной форме. Я нашел ее очень полезной и вдохновляющей!

Статья содержит анализ причин и последствий проблемы, что позволяет лучше понять ее важность и сложность.

Позиция автора остается нейтральной, что позволяет читателям сформировать свое мнение.

Автор предоставляет разнообразные источники для более глубокого изучения темы.

Автор старается оставаться нейтральным, что помогает читателям получить полную картину и рассмотреть разные аспекты темы.

Автор старается предоставить достоверную информацию, не влияя на оценку читателей. Это сообщение отправлено с сайта https://ru.gototop.ee/

Write more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seems as though you relied on the video to make your point. You definitely know what youre talking about, why throw away your intelligence on just posting videos to your blog when you could be giving us something enlightening to read?

Я оцениваю объективный и непредвзятый подход автора к теме.

Статья предлагает конкретные примеры, чтобы проиллюстрировать свои аргументы.

Hi there just wanted to give you a quick heads up and let you know a few of the images aren’t loading properly. I’m not sure why but I think its a linking issue. I’ve tried it in two different web browsers and both show the same outcome.

WOW just what I was searching for. Came here by searching for keyword

If you want to obtain much from this post then you have to apply these techniques to your won blog.

Эта статья является настоящим сокровищем информации. Я был приятно удивлен ее глубиной и разнообразием подходов к рассматриваемой теме. Спасибо автору за такой тщательный анализ и интересные факты!

Статья содержит систематическую аналитику темы, учитывая разные аспекты проблемы.

Hi there I am so happy I found your blog, I really found you by mistake, while I was researching on Digg for something else, Nonetheless I am here now and would just like to say kudos for a fantastic post and a all round thrilling blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to read it all at the minute but I have book-marked it and also included your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read a great deal more, Please do keep up the excellent work.

If some one wishes to be updated with most recent technologies afterward he must be go to see this web site and be up to date every day.

I gotta favorite this site it seems very beneficial handy

My website: анилингус порно

Автор старается оставаться нейтральным, чтобы читатели могли самостоятельно рассмотреть различные точки зрения и сформировать собственное мнение. Это сообщение отправлено с сайта https://ru.gototop.ee/

Muchos Gracias for your blogReally looking forward to read more Much obliged