[intro]Those who died as a result of the brutal bureaucracy of the Gauteng administration owe us nothing. Their families owe us nothing. What we owe them – what we owe each other – is to claim responsibility for the most vulnerable and to take that responsibility seriously.[/intro]

In South Africa, the average post-rehabilitation life expectancy for someone who survives a traumatic spinal cord injury is two years. That means that, in this country, if you break your neck, and live with a severe disability as a result, chances are you will die within two years of your injury.

The injury itself won’t kill you, but here’s what might: if you are amongst the majority of South Africans living with a disability, you will be discharged into a world that is designed to exclude you. You will find that you need a staggering amount of money (by South African standards), just to get out of bed every morning, never mind leave the house. And if you can’t get out of bed or leave the house, you won’t be able to earn that staggering amount of money, leaving you dependent on what meagre assistance the state can give you, and what your loved ones can and will do for you.

The effects of this may leave you despairing and drained. What may finally kill you, however, will come in the form of what those of us who occupy non-disabled bodies may consider relatively minor. A chesty cough. A bladder infection. A bed sore that becomes a pressure sore.

These are brutal truths to face. I acknowledge that I write about them with the relative remove of someone who has not lived them up close. But I write with some authority, based on what I have learnt in the 10 years I have been partnered with a man living with quadriplegia.

We are incredibly privileged and many of the demons I draw above do not bay as loudly at our door. But they still bay. Our relative access and leverage affords us a variety of strategies to make sure my husband lives a fulfilled life and can be the man, father, son, brother, friend and partner he is to his loved ones. This doesn’t mean he is free of the daily indignities of living in a world that tells you in countless ways, both minor and major, that it does not want you, it is not for you. He is relatively well-protected against the physical ailments that deal the final blow to many TSCI survivors, but he is by no stretch of the imagination protected from the disabling social and physical world all South Africans living with a disability face.

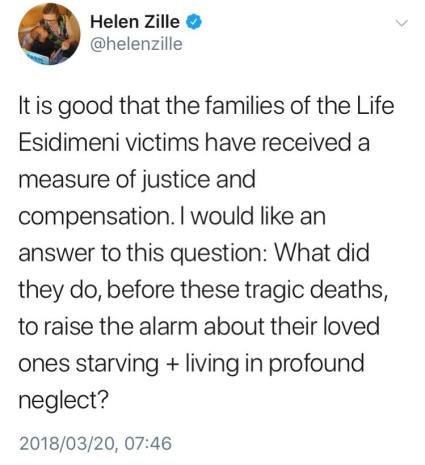

When the ruling in the Life Esidimeni hearings was handed down, acknowledging the callousness that led to the appalling deaths of over 100 people living with mental disabilities, Western Cape Premier Helen Zille thought it prudent to respond thusly:

She was resoundingly and rightly called out for the tweet. However, the attitude underlying her missive is a commonly held one.

The assumption that disabilities are, first and foremost, a personal responsibility is one that runs through our society. Take the state’s paltry disability grant, for example. That’s just what it is – an amount of money, a sum, given to individuals on a monthly basis. What we are effectively saying is that it is up to the disabled to decide how to care for themselves. The best we can do as a society is give them a bit (and I do mean a very little bit) of cash towards that.

If you’re relatively lucky and don’t rely on the state, you can expect a tax break for your troubles. That is, cash after the fact of whatever resources you might need to live an enabled life. Our approach is to throw money at the matter and hope for the best. And in many cases, what we mean by ‘the best’ are the families of those living with disabilities. We are banking on the emotional, economic and physical availability of families to fulfil what we effectively feel are personal, individual needs. If you’re relatively lucky, your family is willing and able to do this. If, like the majority of South Africans living with disabilities, you are not, your family cannot avail themselves to you in the ways you need them to.

In many of those cases, families then rely on institutional support. Loved ones are committed to the care of places like Life Esidimeni. And they are committed precisely because they are loved. Because their families realise that they cannot fulfil complex needs and cannot meet the myriad demands, and therefore find a place, a community that can. Except that’s not what those places are, as the Life Esidimeni case showed. They’re not communities of care, but merely outcrops of our broader, careless society, masquerading as community. That is how, in 2018, people can starve to death.

And that is how, knowing all we know about these shocking deaths, we can still look to grieving families and demand answers. We don’t really believe that disability is our problem. We believe it is a responsibility, rather than a symptom of a disabling society. Instead of looking at Life Esidimeni as an extreme but expected outcome of our violent disregard and deep contempt for people with disabilities, we blame the families. We gave them money, didn’t we? What did they do to ensure their loved ones didn’t die by drowning in their own blood?

The answer, Premier Zille, and dear reader, is that the families trusted society. Even as they suspected they could not, they had few other options, so they trusted. Through this act of trust, the giving over of loved ones to Life Esidimeni for care, we, as a society, had an opportunity to claim collective responsibility for people living with disabilities. Instead, we continued to shirk responsibility, violently so.

Those who died as a result of the brutal bureaucracy of the Gauteng provincial administration owe us nothing. Their families owe us nothing. What we owe them – what we owe each other – is to claim responsibility for those who are most vulnerable and to take that responsibility seriously.

This article first appeared on the blog Rumbi Writes.

Great ?V I should definitely pronounce, impressed with your site. I had no trouble navigating through all the tabs and related info ended up being truly easy to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it at all. Reasonably unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or anything, site theme . a tones way for your client to communicate. Nice task..

Hey, you used to write great, but the last several posts have been kinda boring… I miss your super writings. Past several posts are just a little out of track! come on!

I loved as much as you will receive carried out right here. The sketch is attractive, your authored subject matter stylish. nonetheless, you command get bought an edginess over that you wish be delivering the following. unwell unquestionably come more formerly again as exactly the same nearly a lot often inside case you shield this hike.

Howdy! This post could not be written any better! Reading through this post reminds me of my old room mate! He always kept chatting about this. I will forward this post to him. Fairly certain he will have a good read. Thanks for sharing!

Hello there! I could have sworn I’ve been to this site before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyhow, I’m definitely delighted I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back frequently!

I am really loving the theme/design of your site. Do you ever run into any browser compatibility problems? A number of my blog readers have complained about my website not operating correctly in Explorer but looks great in Chrome. Do you have any advice to help fix this issue?

Yeah bookmaking this wasn’t a high risk decision great post! .

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wished to say that I’ve truly enjoyed surfing around your blog posts. In any case I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you write again soon!

You got a very good website, Glad I detected it through yahoo.

I genuinely treasure your piece of work, Great post.

I like this website so much, saved to bookmarks.

Would you be keen on exchanging links?

Fantastic goods from you, man. I have take into accout your stuff previous to and you’re simply too excellent. I actually like what you have bought here, really like what you’re stating and the way in which by which you assert it. You are making it entertaining and you still care for to stay it sensible. I can’t wait to learn much more from you. This is really a great website.

I appreciate, cause I found just what I was looking for. You have ended my four day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day. Bye

I’m still learning from you, as I’m making my way to the top as well. I certainly enjoy reading all that is posted on your site.Keep the posts coming. I enjoyed it!

Heya i am for the first time here. I came across this board and I find It really helpful & it helped me out much. I’m hoping to give one thing back and aid others such as you helped me.

Just wish to say your article is as surprising. The clearness for your post is simply cool and i could suppose you are knowledgeable on this subject. Fine with your permission allow me to snatch your RSS feed to stay up to date with impending post. Thanks one million and please keep up the rewarding work.

Great site! I am loving it!! Will come back again. I am bookmarking your feeds also.

I’m really impressed along with your writing skills and also with the layout on your blog. Is that this a paid theme or did you customize it your self? Anyway keep up the nice quality writing, it’s rare to see a great weblog like this one nowadays..

Hello my loved one! I want to say that this article is amazing, nice written and come with almost all vital infos. I would like to look more posts like this .

Hello, i think that i saw you visited my blog so i came to “return the favor”.I’m attempting to find things to improve my website!I suppose its ok to use a few of your ideas!!

Good write-up, I’m regular visitor of one’s web site, maintain up the excellent operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.

You really make it seem so easy with your presentation but I find this matter to be really something that I think I would never understand. It seems too complicated and very broad for me. I am looking forward for your next post, I will try to get the hang of it!

Can I simply say what a relief to find somebody who really is aware of what theyre speaking about on the internet. You definitely know find out how to deliver an issue to gentle and make it important. More people need to read this and perceive this facet of the story. I cant consider youre not more widespread since you positively have the gift.

I’m very happy to read this. This is the type of manual that needs to be given and not the random misinformation that is at the other blogs. Appreciate your sharing this greatest doc.

I really like your writing style, excellent information, thanks for putting up : D.

I really like your writing style, good information, appreciate it for putting up :D. “If a cluttered desk is the sign of a cluttered mind, what is the significance of a clean desk” by Laurence J. Peter.

I like what you guys are usually up too. This sort of clever work and exposure! Keep up the superb works guys I’ve incorporated you guys to my own blogroll.

Heya i am for the first time here. I found this board and I find It really useful & it helped me out much. I hope to give something back and help others like you aided me.

I beloved as much as you will obtain performed proper here. The cartoon is attractive, your authored material stylish. however, you command get bought an impatience over that you wish be turning in the following. unwell surely come more until now again since precisely the same nearly very continuously within case you shield this increase.

hey there and thank you for your info – I have certainly picked up something new from right here. I did however expertise several technical issues using this web site, as I experienced to reload the website many times previous to I could get it to load properly. I had been wondering if your web hosting is OK? Not that I am complaining, but sluggish loading instances times will sometimes affect your placement in google and could damage your quality score if advertising and marketing with Adwords. Well I’m adding this RSS to my email and could look out for much more of your respective fascinating content. Ensure that you update this again soon..

I was suggested this web site by my cousin. I am not sure whether this post is written by him as no one else know such detailed about my difficulty. You’re incredible! Thanks!

I’d have to examine with you here. Which is not one thing I usually do! I take pleasure in reading a post that may make folks think. Additionally, thanks for permitting me to comment!

It’s really a cool and helpful piece of information. I’m glad that you shared this useful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

Great post, you have pointed out some wonderful points, I besides conceive this s a very good website.

Have you ever considered about including a little bit more than just your articles? I mean, what you say is fundamental and everything. But think about if you added some great graphics or video clips to give your posts more, “pop”! Your content is excellent but with pics and video clips, this website could definitely be one of the greatest in its field. Excellent blog!

Hmm is anyone else experiencing problems with the pictures on this blog loading? I’m trying to find out if its a problem on my end or if it’s the blog. Any feedback would be greatly appreciated.

I really appreciate this post. I’ve been looking all over for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You’ve made my day! Thank you again!

Super-Duper blog! I am loving it!! Will come back again. I am taking your feeds also

An impressive share, I just given this onto a colleague who was doing a little analysis on this. And he in fact bought me breakfast because I found it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the treat! But yeah Thnkx for spending the time to discuss this, I feel strongly about it and love reading more on this topic. If possible, as you become expertise, would you mind updating your blog with more details? It is highly helpful for me. Big thumb up for this blog post!

I like the efforts you have put in this, thankyou for all the great articles.

Video Marketing Explained And Why Every Business Should Use It

Very mice post, will share it on my social media network

I truly enjoy studying on this site, it has got fantastic posts. “A man of genius has been seldom ruined but by himself.” by Samuel Johnson.

Regards for this post, I am a big fan of this internet site would like to go on updated.

Backlinks generator software helping you to generate over 12 million backlinks for any link in minutes. Easy to operate and provide you with full report of all created backlinks. Ideal for personal use or start your own online business.

I am glad that I detected this site, exactly the right information that I was searching for! .

I am really impressed together with your writing abilities as smartly as with the structure for your weblog. Is this a paid subject or did you customize it your self? Either way keep up the nice quality writing, it is uncommon to look a nice weblog like this one these days..

Great – I should certainly pronounce, impressed with your website. I had no trouble navigating through all tabs and related information ended up being truly simple to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it at all. Quite unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or something, site theme . a tones way for your client to communicate. Nice task.

I just couldn’t depart your site prior to suggesting that I really enjoyed the standard info a person provide for your visitors? Is gonna be back often in order to check up on new posts

Hi my friend! I want to say that this article is awesome, great written and come with approximately all important infos. I would like to peer more posts like this .

Some genuinely choice content on this website , saved to favorites.

Hi there! Do you know if they make any plugins to protect against hackers? I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any suggestions?

I’ve been absent for a while, but now I remember why I used to love this web site. Thank you, I will try and check back more often. How frequently you update your site?

I think other web site proprietors should take this web site as an model, very clean and wonderful user genial style and design, let alone the content. You’re an expert in this topic!

Excellent blog post here and useful information. Thank you very much for sharing your experience and good luck in future blogging

Howdy! I could have sworn I’ve been to this site before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyhow, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back frequently!

Hiya! I simply would like to give an enormous thumbs up for the great information you have got right here on this post. I will be coming back to your blog for more soon.

fantastic issues altogether, you simply gained a new reader. What might you suggest in regards to your submit that you just made some days ago? Any positive?

I am not positive the place you are getting your information, but great topic. I needs to spend some time learning much more or working out more. Thank you for wonderful info I used to be looking for this information for my mission.

I have been checking out a few of your posts and i can state pretty clever stuff. I will make sure to bookmark your blog.

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive learn something like this before. So nice to search out somebody with some original thoughts on this subject. realy thanks for beginning this up. this web site is one thing that is needed on the web, somebody with a bit originality. useful job for bringing one thing new to the web!

I’ll right away grab your rss as I can not find your email subscription link or e-newsletter service. Do you have any? Please let me know so that I could subscribe. Thanks.

Outstanding post, you mentioned some great points in this article. Nice writing skills. Thank you!

Have you ever considered about adding a little bit more than just your articles? I mean, what you say is fundamental and everything. Nevertheless think about if you added some great pictures or video clips to give your posts more, “pop”! Your content is excellent but with pics and videos, this blog could certainly be one of the greatest in its niche. Fantastic blog!

Probably one of the best articles i have read in long long time. Enjoyed it. Thank you for such nice post.

Definitely a magnificent site and revealing posts, I surely will bookmark your website.Best Regards!

Some very interesting points made in this post. Glad i found it. Thanks for sharing such valuable information.

Incredible points made in this article. Outstanding arguments. Keep up the great work. LOVE your writing skills

Definitely a magnificent site and revealing posts, I surely will bookmark your website.Best Regards!

It?s really a nice and useful piece of information. I am glad that you shared this useful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

I have noticed that in unwanted cameras, specialized devices help to {focus|concentrate|maintain focus|target|a**** automatically. The sensors connected with some digital cameras change in contrast, while others employ a beam of infra-red (IR) light, especially in low lighting. Higher specs cameras often use a mixture of both techniques and will often have Face Priority AF where the camera can ‘See’ some sort of face and focus only on that. Many thanks for sharing your thinking on this blog.

Simply desire to say your article is as astounding. The clarity in your post is just nice and i can assume you’re an expert on this subject. Fine with your permission allow me to grab your RSS feed to keep up to date with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please continue the rewarding work.

Today, while I was at work, my sister stole my iphone and tested to see if it can survive a thirty foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My iPad is now broken and she has 83 views. I know this is entirely off topic but I had to share it with someone!

Thx for your post. I would really like to say that the cost of car insurance differs a lot from one policy to another, for the reason that there are so many different facets which give rise to the overall cost. By way of example, the make and model of the auto will have a significant bearing on the price tag. A reliable ancient family vehicle will have an inexpensive premium than just a flashy expensive car.

I used to be very happy to find this internet-site.I wanted to thanks for your time for this glorious learn!! I undoubtedly enjoying each little little bit of it and I’ve you bookmarked to take a look at new stuff you blog post.

https://concise.ng/tiwa-savage-opens-marriage-reconciliation-tee-billz

I appreciate, cause I discovered exactly what I was looking for. You’ve ended my four day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a nice day. Bye

Heya just wanted to give you a brief heads up and let you know a few of the images aren’t loading correctly. I’m not sure why but I think its a linking issue. I’ve tried it in two different web browsers and both show the same outcome.

It?s actually a cool and useful piece of info. I am glad that you simply shared this useful information with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

Hey! Do you know if they make any plugins to assist with Search Engine Optimization? I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good results. If you know of any please share. Appreciate it!

Thank you for another informative site. Where else could I get that type of information written in such a perfect way? I’ve a project that I’m just now working on, and I have been on the look out for such info.

Thanks for the suggestions you have discussed here. Something important I would like to say is that laptop or computer memory demands generally increase along with other innovations in the technologies. For instance, when new generations of processor chips are brought to the market, there’s usually a matching increase in the shape demands of all personal computer memory as well as hard drive room. This is because the software operated by way of these processor chips will inevitably increase in power to benefit from the new technology.

Hello, I do think your web site could possibly be having web browser compatibility problems. Whenever I look at your site in Safari, it looks fine however, when opening in I.E., it has some overlapping issues. I just wanted to provide you with a quick heads up! Besides that, excellent site.

Hey There. I found your weblog using msn. That is a very smartly written article. I will be sure to bookmark it and return to read more of your helpful info. Thanks for the post. I?ll certainly comeback.

Attractive section of content. I just stumbled upon your blog and in accession capital to assert that I acquire in fact enjoyed account your blog posts. Anyway I?ll be subscribing to your augment and even I achievement you access consistently quickly.

This is a good tip especially to those fresh to the blogosphere. Simple but very accurate information… Appreciate your sharing this one. A must read post!

One more thing I would like to convey is that instead of trying to match all your online degree courses on days that you conclude work (since the majority people are worn out when they return home), try to obtain most of your classes on the saturdays and sundays and only one or two courses in weekdays, even if it means taking some time away from your weekend. This pays off because on the week-ends, you will be far more rested plus concentrated on school work. Thanks a lot for the different recommendations I have learned from your web site.

Some genuinely fantastic blog posts on this web site, thanks for contribution. “My salad days, When I was green in judgment.” by William Shakespeare.

It’s hard to come by experienced people on this topic, however, you seem like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

But wanna remark on few general things, The website design and style is perfect, the content is very excellent. “The stars are constantly shining, but often we do not see them until the dark hours.” by Earl Riney.

Thanks for any other great article. The place else may anybody get that kind of info in such a perfect way of writing? I have a presentation next week, and I’m at the search for such information.

Thanks for all your efforts that you have put in this. very interesting information.

Good day! I could have sworn I’ve been to this website before but after reading through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyhow, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!

I just could not depart your web site before suggesting that I actually enjoyed the standard information a person provide for your visitors? Is gonna be back often in order to check up on new posts

Very interesting topic, appreciate it for posting. “The great aim of education is not knowledge but action.” by Herbert Spencer.

There’s definately a great deal to find out about this topic. I really like all the points you made.

I haven¦t checked in here for some time as I thought it was getting boring, but the last few posts are good quality so I guess I will add you back to my daily bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

I keep listening to the news broadcast lecture about getting free online grant applications so I have been looking around for the top site to get one. Could you tell me please, where could i acquire some?

You can definitely see your enthusiasm in the work you write. The world hopes for even more passionate writers like you who aren’t afraid to say how they believe. Always go after your heart.

Definitely, what a splendid blog and educative posts, I surely will bookmark your site.Have an awsome day!

Hello. impressive job. I did not anticipate this. This is a impressive story. Thanks!

Some genuinely interesting points you have written.Assisted me a lot, just what I was looking for : D.

I dugg some of you post as I cerebrated they were very helpful invaluable

so much good info on here, : D.

I am not rattling excellent with English but I come up this really easygoing to translate.

Pretty part of content. I simply stumbled upon your site and in accession capital to say that I acquire in fact loved account your weblog posts. Any way I’ll be subscribing to your feeds or even I fulfillment you get right of entry to consistently quickly.

This internet site is my intake, really superb style and design and perfect content material.

Appreciate it for all your efforts that you have put in this. very interesting info .

As a Newbie, I am constantly browsing online for articles that can benefit me. Thank you

I precisely wanted to appreciate you once more. I do not know the things that I would have tried without the actual suggestions shared by you regarding that topic. Certainly was a real distressing dilemma for me, however , being able to see a new skilled way you managed it forced me to weep for joy. I am grateful for this guidance and expect you know what a great job that you are putting in instructing most people via your webblog. Most likely you have never met any of us.

Together with everything that seems to be developing throughout this subject material, a significant percentage of perspectives tend to be very exciting. Having said that, I beg your pardon, but I do not subscribe to your entire strategy, all be it radical none the less. It looks to everybody that your opinions are generally not totally justified and in reality you are your self not even totally certain of the point. In any case I did enjoy reading it.

I have not checked in here for some time because I thought it was getting boring, but the last several posts are good quality so I guess I’ll add you back to my everyday bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

Great line up. We will be linking to this great article on our site. Keep up the good writing.

You have mentioned very interesting points! ps nice website.

As a Newbie, I am always browsing online for articles that can be of assistance to me. Thank you

Hi my friend! I wish to say that this article is awesome, nice written and include approximately all vital infos. I would like to peer more posts like this .

I’ve recently started a website, the info you provide on this web site has helped me tremendously. Thanks for all of your time & work.

Thanks for another excellent post. The place else could anybody get that type of information in such an ideal means of writing? I have a presentation next week, and I’m at the search for such info.

You are a very clever individual!

My partner and I absolutely love your blog and find nearly all of your post’s to be exactly I’m looking for. Does one offer guest writers to write content to suit your needs? I wouldn’t mind writing a post or elaborating on a number of the subjects you write concerning here. Again, awesome website!

Keep up the excellent piece of work, I read few posts on this site and I think that your web site is real interesting and has got sets of fantastic information.

Currently it looks like Movable Type is the preferred blogging platform out there right now. (from what I’ve read) Is that what you are using on your blog?

Thanks a lot for sharing this with all of us you really know what you are talking about! Bookmarked. Kindly also visit my site =). We could have a link exchange agreement between us!

I got good info from your blog

Fantastic website you have here but I was curious about if you knew of any community forums that cover the same topics discussed in this article? I’d really love to be a part of community where I can get suggestions from other experienced individuals that share the same interest. If you have any suggestions, please let me know. Many thanks!

very nice publish, i definitely love this website, keep on it

I have been absent for some time, but now I remember why I used to love this blog. Thank you, I’ll try and check back more often. How frequently you update your website?

Hi there just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The text in your article seem to be running off the screen in Firefox. I’m not sure if this is a formatting issue or something to do with web browser compatibility but I figured I’d post to let you know. The layout look great though! Hope you get the issue fixed soon. Kudos

Thanks for another fantastic post. Where else may just anybody get that kind of info in such a perfect approach of writing? I have a presentation next week, and I’m at the search for such info.

Some really nice stuff on this site, I like it.

I genuinely enjoy looking at on this site, it holds superb posts.

Utterly composed subject matter, appreciate it for information .

My spouse and i felt very fortunate Michael managed to finish off his reports while using the ideas he had in your web site. It’s not at all simplistic to just continually be handing out guidance which often men and women may have been selling. And we do know we have got the writer to give thanks to because of that. All the explanations you made, the easy blog navigation, the relationships you will make it easier to engender – it’s got most fabulous, and it is helping our son in addition to us recognize that the concept is fun, which is certainly extremely fundamental. Thanks for all the pieces!

I truly appreciate this post. I have been looking all over for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You’ve made my day! Thx again

Aw, this was a very nice post. In concept I want to put in writing like this moreover ? taking time and precise effort to make a very good article? however what can I say? I procrastinate alot and in no way seem to get something done.

F*ckin’ awesome things here. I am very glad to see your article. Thanks a lot and i’m looking forward to contact you. Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?

Hello my friend! I want to say that this post is awesome, nice written and include almost all significant infos. I’d like to see more posts like this.

When I originally commented I clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get four emails with the same comment. Is there any way you can remove me from that service? Thanks!

I’m more than happy to discover this website. I need to to thank you for ones time due to this fantastic read!! I definitely savored every little bit of it and I have you saved as a favorite to look at new things on your site.

I am impressed with this internet site, very I am a big fan .

Neat blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere?

A theme like yours with a few simple adjustements would

really make my blog jump out. Please let me know where you got your theme.

Thanks a lot

Thank you a lot for sharing this with all people you actually understand what you are speaking approximately! Bookmarked. Please additionally seek advice from my site =). We could have a link alternate arrangement among us!

I got what you intend,bookmarked, very decent web site.

wonderful publish, very informative. I’m wondering why the other specialists of this sector do not understand this. You should proceed your writing. I’m confident, you’ve a great readers’ base already!

I’d have to check with you here. Which is not something I often do! I get pleasure from studying a publish that may make people think. Also, thanks for allowing me to remark!

I’m really enjoying the theme/design of your blog. Do you ever run into any web browser compatibility issues? A couple of my blog visitors have complained about my blog not operating correctly in Explorer but looks great in Chrome. Do you have any ideas to help fix this problem?

A person necessarily assist to make significantly posts I would state. This is the very first time I frequented your website page and so far? I amazed with the research you made to create this actual publish amazing. Fantastic process!

When I originally commented I clicked the “Notify me when new comments are added” checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get four emails with the same comment. Is there any way you can remove me from that service? Bless you!

Thank you for sharing superb informations. Your site is so cool. I’m impressed by the details that you have on this web site. It reveals how nicely you perceive this subject. Bookmarked this website page, will come back for extra articles. You, my friend, ROCK! I found simply the info I already searched everywhere and just couldn’t come across. What a great website.

Merely wanna input that you have a very decent website , I like the pattern it actually stands out.

You can definitely see your expertise within the work you write. The arena hopes for more passionate writers such as you who are not afraid to mention how they believe. All the time go after your heart.

It is in reality a nice and helpful piece of info. I am happy that you simply shared this useful info with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

I would like to thank you for the efforts you’ve put in writing this website. I am hoping the same high-grade website post from you in the upcoming also. Actually your creative writing abilities has inspired me to get my own site now. Really the blogging is spreading its wings quickly. Your write up is a great example of it.

Thanks for the tips you are discussing on this blog site. Another thing I would like to say is that getting hold of duplicates of your credit report in order to inspect accuracy of each and every detail will be the first step you have to undertake in repairing credit. You are looking to cleanse your credit report from detrimental details problems that wreck your credit score.

I enjoy you because of each of your labor on this web site. My mother take interest in working on internet research and it’s easy to understand why. I hear all regarding the dynamic means you give worthwhile strategies by means of the blog and even inspire participation from other individuals on that point and our princess has always been learning a whole lot. Take advantage of the rest of the year. You’re the one doing a tremendous job.

I have been exploring for a bit for any high quality articles or blog posts on this sort of area . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this website. Reading this information So i am happy to convey that I’ve an incredibly good uncanny feeling I discovered exactly what I needed. I most certainly will make sure to do not forget this website and give it a look regularly.

Howdy very cool blog!! Man .. Excellent .. Wonderful .. I’ll bookmark your website and take the feeds also…I am satisfied to find a lot of useful information right here within the submit, we need develop more strategies in this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

Wonderful blog! I found it while searching on Yahoo News. Do you have any suggestions on how to get listed in Yahoo News? I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get there! Thank you

Delve into the Lightning Network: Bitcoins layer-2 solution enhancing speed and reducing fees. Understand its mechanics, benefits, and transformative potential.

Howdy! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after reading through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Nonetheless, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!

Hello.This post was extremely interesting, particularly since I was looking for thoughts on this topic last week.

I have been surfing on-line more than three hours as of late, but I by no means found any attention-grabbing article like yours. It is lovely price sufficient for me. In my opinion, if all website owners and bloggers made just right content material as you did, the internet will probably be much more useful than ever before.

It’s in reality a great and helpful piece of information. I am glad that you just shared this helpful info with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

Good – I should certainly pronounce, impressed with your site. I had no trouble navigating through all the tabs as well as related info ended up being truly simple to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it in the least. Reasonably unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or anything, website theme . a tones way for your client to communicate. Excellent task.

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain nice points in features also.

It?¦s in reality a great and useful piece of information. I?¦m glad that you just shared this useful information with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

What’s Happening i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve found It absolutely useful and it has aided me out loads. I hope to contribute & help other users like its helped me. Great job.

I think this internet site contains some rattling good information for everyone : D.

Hi, I think your site might be having browser compatibility issues. When I look at your website in Safari, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, fantastic blog!

Thanks for giving your ideas. I’d personally also like to state that video games have been ever before evolving. Technology advances and innovative developments have aided create realistic and fun games. Most of these entertainment games were not as sensible when the concept was being experimented with. Just like other areas of technology, video games as well have had to develop through many many years. This is testimony on the fast growth of video games.

Wonderful blog! I found it while browsing on Yahoo News. Do you have any tips on how to get listed in Yahoo News? I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get there! Many thanks

Well I definitely liked reading it. This information procured by you is very effective for proper planning.

Nice weblog here! Also your website lots up very fast! What host are you using? Can I am getting your associate hyperlink to your host? I desire my website loaded up as fast as yours lol

Howdy, i read your blog occasionally and i own a similar one and i was just wondering if you get a lot of spam comments? If so how do you prevent it, any plugin or anything you can suggest? I get so much lately it’s driving me mad so any help is very much appreciated.

There are some fascinating time limits in this article but I don’t know if I see all of them heart to heart. There is some validity but I’ll take maintain opinion till I look into it further. Good article , thanks and we would like more! Added to FeedBurner as effectively

An interesting discussion is worth comment. I think that you should write more on this topic, it might not be a taboo subject but generally people are not enough to speak on such topics. To the next. Cheers

Thanks – Enjoyed this update, is there any way I can receive an email sent to me whenever you publish a fresh article?

I think this internet site has got some really excellent information for everyone :D. “Morality, like art, means a drawing a line someplace.” by Oscar Wilde.

Thanks for all of your efforts on this web page. My daughter takes pleasure in setting aside time for investigations and it is easy to understand why. My partner and i notice all concerning the dynamic mode you convey advantageous tips and tricks via the web blog and as well encourage contribution from website visitors on this situation and our own girl is undoubtedly learning so much. Enjoy the remaining portion of the year. Your conducting a very good job.

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain nice points in features also.

What i do not realize is in fact how you’re no longer really a lot more neatly-liked than you might be now. You are so intelligent. You realize thus significantly in terms of this subject, made me individually consider it from so many various angles. Its like women and men are not interested unless it is one thing to do with Lady gaga! Your individual stuffs outstanding. Always care for it up!

Restoran ini menyediakan opsi menu yang cocok untuk semua anggota keluarga, dari anak-anak hingga orang dewasa.

https://foodparadise.network/seminyak-best-restaurants-cafes/

The service is prompt and attentive, ensuring a seamless dining experience.

1xBet Promo Code 2023: 248248 – this combination gives you an exclusive sports bonus that will add 100 to your first deposit of up to 130 €/$. Promo codes have become widespread in the gambling industry, including betting. In other words, game portals provide benefits and advantages to players under certain conditions. Such a sentence is usually encrypted in a combination consisting of numbers, letters and symbols. It is this combination that is a promo code. It is with this combination that users most often encounter when they are interested in the 1xBet bookmaker.

Great write-up, I’m normal visitor of one’s blog, maintain up the excellent operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.

I love your writing style really enjoying this internet site.

Valuable info. Lucky me I found your site by accident, and I am shocked why this accident did not happened earlier! I bookmarked it.

obviously like your web-site but you have to check the spelling on several of your posts. A number of them are rife with spelling issues and I in finding it very troublesome to tell the truth then again I will surely come again again.

Info Pekerja Bali adalah alat penting bagi siapa saja yang serius tentang membangun karier di Bali.

Fantastic website. Plenty of useful information here. I¦m sending it to some pals ans also sharing in delicious. And certainly, thank you for your effort!

This is a really good read for me, Must admit that you are one of the best bloggers I ever saw.Thanks for posting this informative article.

I think other site proprietors should take this website as an model, very clean and wonderful user genial style and design, let alone the content. You’re an expert in this topic!

I do agree with all the ideas you’ve presented in your post. They’re really convincing and will definitely work. Still, the posts are very short for novices. Could you please extend them a little from next time? Thanks for the post.

I am extremely impressed with your writing skills and also with the layout on your blog. Is this a paid theme or did you customize it yourself? Anyway keep up the nice quality writing, it is rare to see a great blog like this one these days..

What i do not understood is in truth how you’re no longer actually much more smartly-liked than you may be now. You are so intelligent. You know thus significantly in relation to this topic, produced me individually consider it from numerous various angles. Its like men and women are not interested unless it’s one thing to accomplish with Woman gaga! Your personal stuffs great. Always take care of it up!

Informasi pekerjaan yang selalu terkini, terima kasih kepada mereka.

Hi there, i read your blog from time to time and i own a similar one and i was just wondering if you get a lot of spam responses? If so how do you stop it, any plugin or anything you can recommend? I get so much lately it’s driving me crazy so any help is very much appreciated.

I like this website very much, Its a very nice position to read and obtain info . “There is no exercise better for the heart than reaching down and lifting people up.” by John Andrew Holmes.

Hiya, I am really glad I have found this information. Nowadays bloggers publish just about gossips and web and this is really frustrating. A good website with interesting content, this is what I need. Thanks for keeping this website, I’ll be visiting it. Do you do newsletters? Cant find it.

The other day, while I was at work, my cousin stole my iPad and tested to see if it can survive a thirty foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My apple ipad is now destroyed and she has 83 views. I know this is entirely off topic but I had to share it with someone!

Hello, i think that i noticed you visited my web site thus i got here to “return the favor”.I am attempting to find things to enhance my site!I assume its good enough to use some of your concepts!!

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and wanted to say that I’ve really enjoyed surfing around your blog posts. In any case I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you write again very soon!

I have been absent for a while, but now I remember why I used to love this blog. Thanks, I will try and check back more frequently. How frequently you update your web site?

Situs yang memberikan banyak dukungan bagi pencari kerja, dari awal hingga akhir.

Do you mind if I quote a few of your articles as long as I provide credit and sources back to your site? My website is in the exact same niche as yours and my visitors would truly benefit from a lot of the information you present here. Please let me know if this okay with you. Cheers!

Hallo! Benutzt du Twitter? Ich würde dir gerne folgen, wenn das okay wäre. Ich genieße definitiv Ihren Blog und freue mich auf neue Updates.

I like this post, enjoyed this one thanks for putting up.

Usually I do not learn article on blogs, but I would like to say that this write-up very compelled me to take a look at and do it! Your writing style has been amazed me. Thank you, very nice article.

Great blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere? A design like yours with a few simple adjustements would really make my blog jump out. Please let me know where you got your design. Thanks

I love the efforts you have put in this, thanks for all the great content.

I love it when people come together and share opinions, great blog, keep it up.

Thankyou for this terrific post, I am glad I detected this site on yahoo.

It’s actually a great and helpful piece of information. I’m glad that you shared this useful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

You made some good points there. I looked on the internet for the subject matter and found most persons will go along with with your blog.

Gracias por compartir información excelente. Tu sitio web es muy genial. Estoy impresionado por los detalles que tienes en este sitio web. Revela lo bien que comprendes este tema. Esta página del sitio web se agregó a favoritos y volverá para ver extra artículos. ¡Tú, mi amigo, ROCK! Encontré solo la información que ya busqué por todas partes y solo no pude encontrar. Qué un perfecto sitio.

The heart of your writing whilst appearing reasonable originally, did not really sit perfectly with me personally after some time. Someplace within the paragraphs you were able to make me a believer unfortunately only for a short while. I however have got a problem with your leaps in assumptions and one might do nicely to fill in those gaps. In the event that you actually can accomplish that, I would definitely end up being fascinated.

As I web-site possessor I believe the content matter here is rattling magnificent , appreciate it for your efforts. You should keep it up forever! Good Luck.

I’d have to examine with you here. Which is not one thing I usually do! I take pleasure in reading a post that may make folks think. Additionally, thanks for permitting me to comment!

Fantastic post however , I was wanting to know if you could write a litte more on this topic? I’d be very grateful if you could elaborate a little bit further. Cheers!

I would like to thnkx for the efforts you have put in writing this blog. I am hoping the same high-grade blog post from you in the upcoming as well. In fact your creative writing abilities has inspired me to get my own blog now. Really the blogging is spreading its wings quickly. Your write up is a good example of it.

Hey there! I know this is kinda off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could locate a captcha plugin for my comment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having problems finding one? Thanks a lot!

You should take part in a contest for one of the best blogs on the web. I will recommend this site!

Its like you read my mind! You seem to know so much about this, like you wrote the book in it or something. I think that you could do with a few pics to drive the message home a little bit, but instead of that, this is wonderful blog. An excellent read. I’ll certainly be back.

Hey there! Would you mind if I share your blog with my zynga group? There’s a lot of folks that I think would really enjoy your content. Please let me know. Cheers

Hi there, just become alert to your blog through Google, and located that it’s truly informative. I’m going to watch out for brussels. I will appreciate for those who continue this in future. Lots of other folks will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

Do you have a spam issue on this site; I also am a blogger, and I was wanting to know your situation; many of us have created some nice methods and we are looking to exchange techniques with other folks, why not shoot me an e-mail if interested.

fantastic submit, very informative. I wonder why the opposite specialists of this sector do not understand this. You should proceed your writing. I’m confident, you’ve a huge readers’ base already!

I truly enjoy looking at on this site, it has great blog posts. “Those who complain most are most to be complained of.” by Matthew Henry.

The subsequent time I read a blog, I hope that it doesnt disappoint me as much as this one. I mean, I know it was my option to read, however I really thought youd have something fascinating to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about something that you can repair should you werent too busy looking for attention.

I regard something really special in this internet site.

of course like your web-site but you need to test the spelling on quite a few of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling problems and I to find it very troublesome to inform the reality on the other hand I’ll definitely come again again.

Hiya, I am really glad I’ve found this info. Nowadays bloggers publish only about gossips and net and this is really irritating. A good blog with interesting content, this is what I need. Thanks for keeping this website, I’ll be visiting it. Do you do newsletters? Can not find it.

This design is wicked! You definitely know how to keep a reader entertained. Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Excellent job. I really enjoyed what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it. Too cool!

You have remarked very interesting points! ps decent website . “Hares can gamble over the body of a dead lion.” by Publilius Syrus.

Well I truly liked reading it. This article provided by you is very effective for proper planning.

Can I just say what a relief to find someone who actually knows what theyre talking about on the internet. You definitely know how to bring an issue to light and make it important. More people need to read this and understand this side of the story. I cant believe youre not more popular because you definitely have the gift.

Definitely, what a fantastic website and revealing posts, I will bookmark your website.Have an awsome day!

Oh my goodness! a tremendous article dude. Thanks Nevertheless I am experiencing situation with ur rss . Don’t know why Unable to subscribe to it. Is there anyone getting an identical rss downside? Anybody who knows kindly respond. Thnkx

Good day! Do you know if they make any plugins to protect against hackers?

I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any suggestions?

As a Newbie, I am permanently exploring online for articles that can be of assistance to me. Thank you

You have brought up a very fantastic details, thankyou for the post.

I always spent my half an hour to read this web site’s articles daily along with a mug of coffee.

Saya suka desain antarmuka Info Pekerja Bali yang sederhana dan mudah dipahami. Pencarian pekerjaan menjadi lebih menyenangkan.

I’m not sure why but this website is loading very slow for me. Is anyone else having this issue or is it a issue on my end? I’ll check back later and see if the problem still exists.

Great blog right here! Also your web site a lot up fast! What web host are you using?

Can I am getting your affiliate hyperlink in your host?

I want my site loaded up as fast as yours lol

Discover the essentials of Mempool in blockchain: its role, function in transaction processing, and impact on network efficiency. A concise guide for all.

There may be noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made sure nice points in features also.

You can definitely see your skills within the paintings you write. The arena hopes for even more passionate writers like you who are not afraid to say how they believe. At all times go after your heart.

Have you ever thought about creating an e-book or guest authoring on other websites?

I have a blog based upon on the same information you discuss

and would love to have you share some stories/information. I know my subscribers would enjoy your work.

If you’re even remotely interested, feel free to shoot me an email.

Hello there! This is my 1st comment here so I just wanted to give a quick shout out and tell you I really enjoy reading your articles. Can you suggest any other blogs/websites/forums that cover the same topics? Thanks for your time!

I like this blog so much, saved to my bookmarks.

This blog is definitely rather handy since I’m at the moment creating an internet floral website – although I am only starting out therefore it’s really fairly small, nothing like this site. Can link to a few of the posts here as they are quite. Thanks much. Zoey Olsen

Nice read, I just passed this onto a friend who was doing some research on that. And he actually bought me lunch because I found it for him smile Thus let me rephrase that: Thank you for lunch!

I’m typically to running a blog and i really admire your content. The article has actually peaks my interest. I’m going to bookmark your site and hold checking for brand spanking new information.

I think this is among the so much significant info for me. And i am happy reading your article. But wanna statement on few normal things, The site taste is great, the articles is actually nice : D. Just right task, cheers

Great wordpress blog here.. It’s hard to find quality writing like yours these days. I really appreciate people like you! take care

obviously like your web-site however you have to take a look

at the spelling on quite a few of your posts. A number of them are

rife with spelling issues and I in finding it very troublesome to inform the truth nevertheless I will surely come again again.

Частный дом престарелых в Тульской области. Также мы принимаем пожилых людей с Брянской, Орловской, Липецкой, Рязанской, Калужской и Московской областей. Наш пансионат для пожилых людей является…

I’m just commenting to make you understand what a terrific discovery my wife’s princess gained reading your webblog. She figured out a lot of issues, with the inclusion of how it is like to possess an incredible teaching character to make most people clearly learn specified problematic subject matter. You really did more than my desires. I appreciate you for giving these warm and helpful, dependable, informative not to mention cool guidance on your topic to Gloria.

Hiya very cool website!! Guy .. Excellent .. Wonderful .. I’ll bookmark your blog and take the feeds additionally?KI am satisfied to search out so many helpful information here in the put up, we want develop extra techniques on this regard, thank you for sharing. . . . . .

Only wanna remark on few general things, The website layout is perfect, the content is very wonderful. “The enemy is anybody who’s going to get you killed, no matter which side he’s on.” by Joseph Heller.

Magnificent site. Lots of helpful info here. I’m sending it to some pals ans additionally sharing in delicious. And obviously, thank you on your sweat!

Hi there just wanted to give you a quick heads up and let you know a few of the images aren’t loading correctly.

I’m not sure why but I think its a linking issue.

I’ve tried it in two different web browsers and both show

the same outcome.

I do agree with all of the concepts you’ve presented in your post. They’re very convincing and can certainly work. Still, the posts are very short for novices. May just you please extend them a bit from next time? Thanks for the post.

Great write-up, I am regular visitor of one’s web site, maintain up the excellent operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a long time.

Good site! I truly love how it is simple on my eyes and the data are well written. I am wondering how I could be notified when a new post has been made. I’ve subscribed to your RSS which must do the trick! Have a great day!

Hi there, simply changed into alert to your weblog through Google, and found that it’s truly informative. I’m going to watch out for brussels. I will appreciate in the event you continue this in future. Many people might be benefited out of your writing. Cheers!

obviously like your web-site however you need to test the spelling on several of your posts. Several of them are rife with spelling issues and I find it very bothersome to tell the truth on the other hand I’ll surely come again again.

After examine a number of of the blog posts on your web site now, and I truly like your way of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website record and shall be checking again soon. Pls check out my web site as effectively and let me know what you think.

Was passiert ich bin neu dabei, ich bin darüber gestolpert ich habe gefunden es positiv nützlich und es hat mir viel geholfen. Ich hoffe einen Beitrag leisten & andere Benutzer helfen wie es mir geholfen hat. Gut Arbeit.

Very interesting information!Perfect just what I was looking for!

I keep listening to the news update talk about receiving boundless online grant applications so I have been looking around for the best site to get one. Could you tell me please, where could i find some?

wonderful points altogether, you simply won a brand new reader. What could you suggest in regards to your publish that you made some days in the past? Any sure?

Hello my friend! I wish to say that this article is amazing, great written and come with almost all significant infos. I would like to peer extra posts like this .

Hello.This article was really fascinating, particularly since I was looking for thoughts on this issue last Friday.

This blog is definitely rather handy since I’m at the moment creating an internet floral website – although I am only starting out therefore it’s really fairly small, nothing like this site. Can link to a few of the posts here as they are quite. Thanks much. Zoey Olsen

Today, while I was at work, my cousin stole my iphone and tested to see if it can survive a 40 foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My apple ipad is now broken and she has 83 views. I know this is totally off topic but I had to share it with someone!

I just like the valuable information you supply in your articles. I will bookmark your weblog and test again right here regularly. I am reasonably certain I’ll learn lots of new stuff proper right here! Best of luck for the following!

Some really interesting info , well written and broadly user pleasant.

Hello.This article was really fascinating, especially because I was looking for thoughts on this subject last Tuesday.

База отдыха в Подмосковье на берегу озера с пляжем – двухэтажный коттедж, баня + бильярдная, купель, бассейн, камин. Лучшие условия и цены. Нас рекомендуют! Снять коттедж на выходные и на месяц +7(916)671-79-58

There is noticeably a bundle to identify about this. I believe you made some nice points in features also.

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain nice points in features also.

Hi, Neat post. There’s an issue together with your web site in internet explorer, may test this?K IE still is the market chief and a big element of other people will leave out your wonderful writing because of this problem.

Pretty great post. I simply stumbled upon your blog and wished to mention that I have truly loved surfing around your weblog posts. After all I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I’m hoping you write once more very soon!

I gave https://www.cornbreadhemp.com/products/full-spectrum-cbd-gummies a prove for the first habits, and I’m amazed! They tasted smashing and provided a sense of calmness and relaxation. My emphasis melted away, and I slept less ill too. These gummies are a game-changer an eye to me, and I highly endorse them to anyone seeking natural emphasis alleviation and think twice sleep.

hello!,I really like your writing very a lot! proportion we be in contact more about your article on AOL? I require an expert in this house to unravel my problem. Maybe that is you! Having a look forward to see you.

I am always looking online for tips that can aid me. Thx!

Thank you for sharing superb informations. Your website is so cool. I’m impressed by the details that you have on this website. It reveals how nicely you understand this subject. Bookmarked this web page, will come back for extra articles. You, my friend, ROCK! I found simply the info I already searched everywhere and simply couldn’t come across. What an ideal site.

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information. Your website is very useful. Thanks for sharing.

You actually make it seem really easy along with your presentation however I to find this matter to be actually one thing which I think I might by no means understand. It sort of feels too complicated and extremely vast for me. I’m having a look forward in your subsequent put up, I will try to get the hold of it!

We absolutely love your blog and find the majority of your post’s to be just what I’m looking for. can you offer guest writers to write content for yourself? I wouldn’t mind writing a post or elaborating on most of the subjects you write with regards to here. Again, awesome site!

Hi, Neat post. There is a problem with your site in internet explorer, would check this… IE still is the market leader and a huge portion of people will miss your wonderful writing because of this problem.

whoah this blog is wonderful i love reading your articles. Keep up the good work! You know, lots of people are looking around for this info, you can aid them greatly.

Having read this I thought it was very informative. I appreciate you taking the time and effort to put this article together. I once again find myself spending way to much time both reading and commenting. But so what, it was still worth it!

A formidable share, I just given this onto a colleague who was doing just a little analysis on this. And he actually purchased me breakfast as a result of I found it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the deal with! But yeah Thnkx for spending the time to debate this, I really feel strongly about it and love studying more on this topic. If attainable, as you develop into experience, would you mind updating your blog with extra particulars? It’s extremely useful for me. Large thumb up for this weblog post!

I’ve been surfing online greater than three hours lately, but I never found any interesting article like yours. It’s beautiful price sufficient for me. In my view, if all webmasters and bloggers made excellent content material as you did, the web might be a lot more useful than ever before. “No nation was ever ruined by trade.” by Benjamin Franklin.

Super-Duper website! I am loving it!! Will come back again. I am bookmarking your feeds also

I think other site proprietors should take this web site as an model, very clean and magnificent user friendly style and design, let alone the content. You are an expert in this topic!

I’m not sure why but this site is loading incredibly slow for me. Is anyone else having this problem or is it a problem on my end? I’ll check back later and see if the problem still exists.

It’s actually a great and helpful piece of info. I am happy that you simply shared this helpful info with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

I am really enjoying the theme/design of your blog. Do you ever run into any web browser compatibility problems? A handful of my blog visitors have complained about my blog not operating correctly in Explorer but looks great in Opera. Do you have any tips to help fix this problem?

certainly like your web site but you need to check the spelling on several of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling problems and I find it very bothersome to tell the truth nevertheless I’ll definitely come back again.

Heya i’m for the first time here. I found this board and I find It truly useful & it helped me out much. I hope to give something back and help others like you helped me.

I’m in dote on with the cbd products and [url=https://organicbodyessentials.com/products/organic-face-cream ]non toxic moisturizers[/url] ! The serum gave my peel a youthful rise, and the lip balm kept my lips hydrated all day. Eloquent I’m using unsullied, bona fide products makes me guess great. These are in the present climate my must-haves in support of a saucy and nourished look!

I am pleased that I observed this web site, precisely the right info that I was looking for! .

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and wanted to say that I have really enjoyed browsing your blog posts. After all I will be subscribing to your rss feed and I hope you write again very soon!

I truly appreciate this post. I have been looking everywhere for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You’ve made my day! Thank you again

Great ?V I should certainly pronounce, impressed with your site. I had no trouble navigating through all the tabs as well as related information ended up being truly easy to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it in the least. Quite unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or anything, web site theme . a tones way for your client to communicate. Nice task..

It’s laborious to search out knowledgeable people on this matter, but you sound like you realize what you’re speaking about! Thanks

I as well think therefore, perfectly indited post! .

I regard something genuinely special in this internet site.

Hi there! I could have sworn I’ve been to this site before but after reading through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back often!

Woh I like your posts, saved to favorites! .

I wanted to thank you for this great read!! I definitely enjoying every little bit of it I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you post…

Does your site have a contact page? I’m having problems locating it but, I’d like to shoot you an e-mail. I’ve got some ideas for your blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great site and I look forward to seeing it improve over time.

It¦s really a cool and useful piece of info. I am happy that you shared this useful information with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

What i do not realize is actually how you are no longer really a lot more smartly-appreciated than you may be right now. You are so intelligent. You already know therefore significantly when it comes to this subject, produced me in my opinion believe it from so many varied angles. Its like men and women aren’t involved until it is one thing to do with Girl gaga! Your own stuffs nice. All the time maintain it up!

I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you design this website yourself or did you hire someone to do it for you? Plz respond as I’m looking to design my own blog and would like to find out where u got this from. thank you

Its like you learn my thoughts! You seem to know a lot approximately this, like you wrote the guide in it or something. I feel that you could do with a few to drive the message house a little bit, however instead of that, that is wonderful blog. An excellent read. I’ll definitely be back.

It?¦s really a cool and helpful piece of information. I?¦m glad that you simply shared this useful information with us. Please stay us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

Thank you for sharing with us, I believe this website genuinely stands out : D.

My brother suggested I might like this blog. He was entirely right. This post actually made my day. You cann’t imagine just how much time I had spent for this info! Thanks!

I am glad to be one of the visitors on this great site (:, regards for putting up.

ResumeHead is a resume writing company that helps you get ahead in your career. We are a group of certified resume writers who have extensive knowledge and experience in various fields and industries. We know how to highlight your strengths, achievements, and potential in a way that attracts the attention of hiring managers and recruiters. We also offer other services such as cover letter writing, LinkedIn profile optimization, and career coaching. Whether you need a resume for a new job, a promotion, or a career change, we can help you create a resume that showcases your unique value proposition. Contact us today and let us help you get the resume you deserve.

You have noted very interesting points! ps decent web site.

Appreciate it for helping out, superb info. “Riches cover a multitude of woes.” by Menander.

There are some attention-grabbing deadlines in this article but I don’t know if I see all of them middle to heart. There’s some validity but I will take hold opinion till I look into it further. Good article , thanks and we would like more! Added to FeedBurner as well

I do agree with all of the ideas you’ve presented in your post. They are very convincing and will certainly work. Still, the posts are very short for newbies. Could you please extend them a bit from next time? Thanks for the post.

I really value your work, Great post.

I have not checked in here for a while as I thought it was getting boring, but the last several posts are great quality so I guess I?¦ll add you back to my daily bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

Thanks , I have recently been looking for information approximately this topic for ages and yours is the greatest I have discovered till now. But, what about the bottom line? Are you certain concerning the supply?

Attractive component to content. I just stumbled upon your weblog and in accession capital to say that I acquire in fact loved account your blog posts. Any way I will be subscribing to your feeds or even I achievement you get entry to consistently rapidly.

I conceive you have mentioned some very interesting details, thankyou for the post.

hello!,I love your writing very much! share we keep in touch more approximately your article on AOL? I require an expert on this house to unravel my problem. May be that’s you! Taking a look forward to look you.

Hey there! I could have sworn I’ve been to this site before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Nonetheless, I’m definitely glad I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!

I do agree with all of the ideas you have presented in your post. They are really convincing and will definitely work. Still, the posts are too short for novices. Could you please extend them a little from next time? Thanks for the post.

you are in reality a excellent webmaster. The site loading pace is amazing. It seems that you are doing any distinctive trick. In addition, The contents are masterwork. you have done a excellent job on this subject!

Very interesting points you have mentioned, thanks for posting.

I¦ve been exploring for a little bit for any high quality articles or blog posts on this kind of space . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this site. Reading this info So i am satisfied to exhibit that I have an incredibly just right uncanny feeling I came upon exactly what I needed. I such a lot unquestionably will make sure to don¦t put out of your mind this site and provides it a look on a relentless basis.

Hi there! I know this is somewhat off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could get a captcha plugin for my comment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having problems finding one? Thanks a lot!

Rattling nice style and design and good content, nothing else we need : D.

F*ckin’ remarkable issues here. I’m very glad to look your article. Thanks a lot and i am having a look ahead to contact you. Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?

You actually make it seem so easy with your presentation but I find this topic to be actually something that I think I would never understand. It seems too complex and very broad for me. I am looking forward for your next post, I’ll try to get the hang of it!

Hiya, I’m really glad I have found this information. Nowadays bloggers publish just about gossips and internet and this is actually annoying. A good site with exciting content, this is what I need. Thanks for keeping this web-site, I’ll be visiting it. Do you do newsletters? Can’t find it.

Very well written post. It will be supportive to everyone who employess it, as well as myself. Keep doing what you are doing – i will definitely read more posts.

Thank you a bunch for sharing this with all of us you actually recognize what you’re talking about! Bookmarked. Kindly also discuss with my website =). We can have a hyperlink alternate arrangement among us!

he blog was how do i say it… relevant, finally something that helped me. Thanks

I?¦ve read a few excellent stuff here. Definitely worth bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how much effort you set to make this type of excellent informative website.

I wanted to thank you for this great read!! I definitely enjoying every little bit of it I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you post…

It?¦s actually a great and useful piece of info. I?¦m happy that you simply shared this helpful information with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

The subsequent time I learn a blog, I hope that it doesnt disappoint me as much as this one. I mean, I do know it was my choice to read, however I truly thought youd have one thing interesting to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about something that you could repair in case you werent too busy searching for attention.

I think other web site proprietors should take this web site as an model, very clean and wonderful user genial style and design, as well as the content. You’re an expert in this topic!

It’s a pity you don’t have a donate button! I’d most certainly donate to this fantastic blog! I guess for now i’ll settle for bookmarking and adding your RSS feed to my Google account. I look forward to fresh updates and will talk about this website with my Facebook group. Chat soon!

Great tremendous things here. I am very satisfied to see your article. Thanks a lot and i’m taking a look ahead to touch you. Will you please drop me a mail?