We reflect on the life and times of legendary editor Percy Qoboza who transformed The World newspaper from a sensationalist rag to one more in tune with the aspirations of Black South Africans suffering under apartheid.

Percy Qoboza was The World and The World was Percy Qoboza. The destiny of this newspaper was inextricably bound to the will and life experiences of its legendary editor.

A fellow journalist at the time, Thami Mazwai, describes how Qoboza impacted on the destiny of the paper. Mazwai recalls, before Qoboza took over the editorship of The World, ‘parents use to hide it from their children and the black community hated the publication with its stories of rape, murder, divorce and soccer’.

Qoboza, The World & Me

Allow me to share my own personal experience of these times. I bear witness to the courage of the journalism and of the writers of The World. As a teenager at secondary school in Port Elizabeth, I made it my pre- occupation to collect all the editions of the insert Learning World between 1976 and right up to the very last edition in 1977, when the apartheid government banned the paper. Through those pages I educated myself about the Soweto Student Representative Council (SSRC) and its leaders – Tsietsie Mashinini, Dan Sechaba Montsitsi, Murphison Morobe, Tsofomo Sono, Khotso Seatlholo – as well as about science and African history. Sadly I was to lose this collection to one of those many police raids in the early hours of the morning in which everything was turned upside down by men who had no respect for privacy and dignity.

Early Life in Sophiatown

So who was Percy Qoboza? Percy Peter Tshidiso Qoboza was born on 17 January 1938 in Sophiatown, also known as Sof’town or Kofifi. His mother Flora and father Joseph lived in this sprawling freehold township where black people could own property. Qoboza grew up in this ‘close-knit, vibrant and lively community’ where ‘cooking, singing, washing, talking, learning, fighting, partying took place in communal yards and streets’. Life in Kofifi was hard but dominated by ‘cinemas, shebeens, jazz dens, political meetings and tsotsis or gangsters.’ Perhaps it was his experience of the harsh life of Kofifi coupled with ‘growing up in a devout Catholic household’ that made the young man ‘believe from an early age he was destined to become a priest’.

School and Responsibility

He began his schooling at St Cyprian’s Anglican School in Sophiatown. Then he went on to Pax Training College in Pietersburg (now Polokwane) in the then Northern Transvaal (now Limpopo). He then proceeded to Roma University Seminary in Lesotho to study priesthood. And by this time, he was already involved with the Young Christian Workers (YCW) where, according to Van der Walt, ‘he regularly attended religious camps and often touched on the social and political problems of black communities’.

Like many young black men of his age in the black community, he had to abandon his studies after only two years to get back home to take care of his father, who had suffered a stroke, and to look after his sisters.

Municipal Journalist

And so in 1958 he found a job as a clerk with the Johannesburg City Council working at the municipal offices in Soweto. As time went on, he began to have an interest in politics and in 1960 he left his job to join the then all-white Progressive Party as a full-time organiser. This was kept a secret, as black people were not allowed to join whites-only parties. According to Van der Walt, ‘he was opposed to this secrecy and over the years he became known as an honest, courageous and articulate commentator on black oppression’.

It was at a YCW camp in 1962 that he met his future wife, Anne. They were both militants of this young Christian movement started by a Belgian priest Father Joseph Cadijn. His love for this young woman and his need to inform his community and encourage them to improve their situation changed the course of his life, says Van der Walt.

In 1963 Qoboza resigned as party organiser and went to work as a municipal reporter for The World.

Editor of The World

This was a white-owned daily newspaper targeting black readers. Although the paper had a black editor – a former teacher by the name of M.T. Moerane – white editorial directors – Derrick Gill and later Charles Still took editorial decisions. Both Gill and Still were put in place by the Argus Newspaper Group.

In 1967 Qoboza became acting news editor. And in 1974 he was appointed editor of the paper. One of the first things he did was to ask for the removal of the paternalistic editorial director. And he won.

Nieman Fellowship

Then the following year, he was awarded a Nieman Fellowship in Journalism. With his family, he spent a year at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts in the United States. This was to prove a turning point in his life. Of his time at Harvard, he writes:

“For the first time in my life, I could distinguish between what is right and what is wrong. The thing that scared me most was the fact that I had accepted injustice and discrimination as part of our traditional way of life. After my year, the things I had accepted made me angry. It is because of this that the character of my newspaper has changed tremendously.”

The 1970s

And the character of the times changed too. Inside the country, the black students were in the streets refusing to be taught in the medium of Afrikaans, Steve Biko was banned and restricted to Ginsberg in King Williams Town, the Afro hairstyle was the in-thing, as was wearing dashiki shirts while listening to Nina Simone’s “To be young, gifted and black”.

The trial of nine Black People’s Convention (BPC) and South African Students Organisation (SASO) leaders was on in the Pretoria Supreme Court. Mozambique and Angola became independent and the name Samora Machel was on the lips of every serious black youngster.

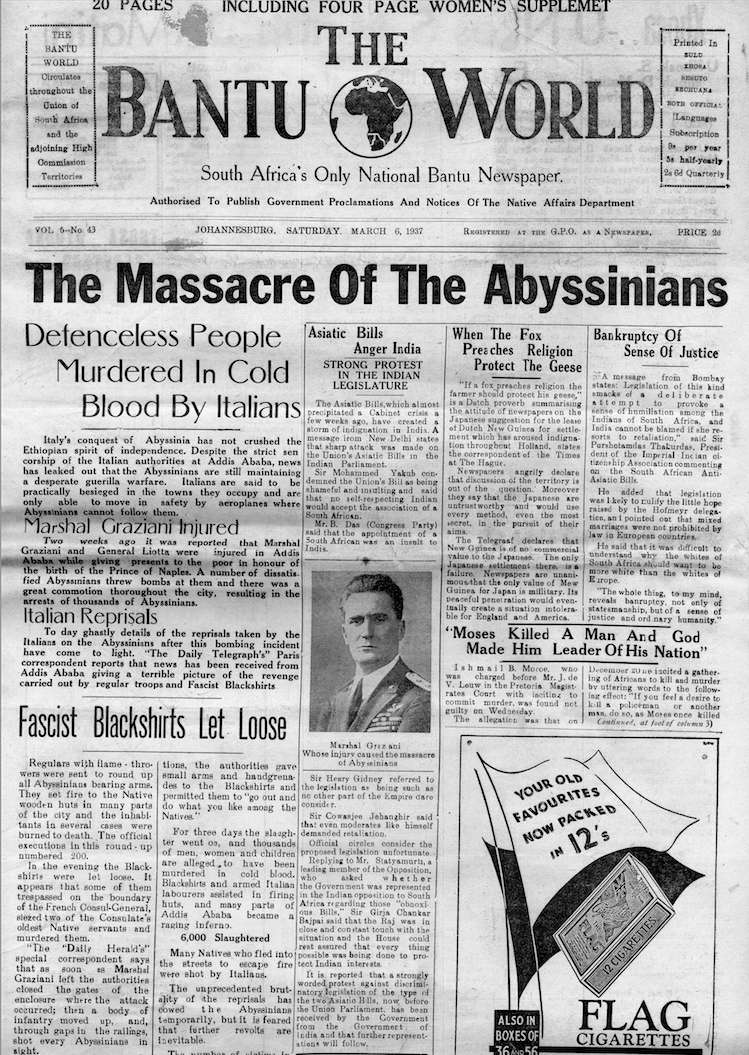

The Bantu World founded in 1932, a forerunner of the paper Percy Qoboza transformed that was banned in 1977.

Transforming The World

Joe Thloloe, a fellow journalist, says Qoboza ‘changed the newspaper from being a soccer, witchcraft and crime sheet crafted out of a white perspective of what black people wanted, into a genuine voice for the black population’. He began to distribute educational supplements in his papers to help black learners overcome the deprivations of ‘Bantu Education’, and promote dialogue between black and white leaders. His office was always open for all who cared about the present and the future of the country. Here the Soweto Committee of Ten, led by Dr Nthato Motlana, was born.

As a Joe Thloloe recalls, Qoboza would send his driver to go and buy iskopo (sheep’s head) and he would sit and eat it there. He also loved his drink – neat brandy. Thloloe says on Sundays, Qoboza liked to send his handwritten leader for the Monday paper with his driver.

The change he brought about in the newsroom has been described as ‘a revolution’. And this changed The World as a newspaper. As Mazwai recalls, ‘within months [he] had changed it into something the black community became proud of.’

About The World in those days, Qoboza says, ‘we were an angry newspaper. For this reason we have made some formidable enemies, and my own personal life is not worth a cent. But I see my role and the role of those people who share my views as articulating, without fear or favour, the aspirations of our people. It is a very hard thing to do.’

Banning & Detention

On a certain Wednesday 19 October 1977, South Africa woke up to be greeted by the headlines “The World is banned!” Seventeen Black Consciousness organisations, including the South African Students Organisation (SASO) and the South African Student’s Movement (SASM) were also banned. The Union of Black Journalists (UBJ) also joined the list of banned organisations. And so, within three years of assuming editorship of the paper, Percy Qoboza was detained at Modderbee Prison in Benoni. There he languished together with fellow journalists Aggrey Klaaste, Willie Bokaba, Godwin Mohlomi, Moffat Zungu, ZB Molefe and Duma ka Ndlovu. Joe Thloloe, Peter Magubane and Gabu Tugwana joined them later. They were held for five and a half months and were only released as a result of international pressure. Many like Mathatha Tsedu, Joe Thloloe and Don Materra were banned upon release.

As soon as he came out of detention, Qoboza was appointed editor of Post and Sunday Post, which had replaced The World and Weekend World. These two were forced to close down in 1980. And in 1981, Qoboza once more left for the United States where he spent time as a guest editor of the Washington Star. A book he wrote titled Comrade Pinkie, was banned in this country but published in the United States. In addition to the Nieman Fellowship, Qoboza received the Pringle Award of the South African Society of Journalists, the Golden Pen of Freedom of the International Publishers Association, and two Honorary Doctorates in Human Letters.

Although he could have chosen to go into exile, he returned to South Africa to continue the fight for freedom. On his return, he worked as an associate editor of the City Press, owned by the publisher of Drum magazine, Jim Bailey. The paper was then sold to the Afrikaans publishing company, Nasionale Pers. In 1986, Qoboza was appointed editor of City Press.

On his fiftieth birthday, 17 January 1988, Percy Peter Tshidiso Qoboza died in hospital after succumbing to cardio-respiratory failure. Thousands came out to honour this soldier of the pen ‘in a four-hour, police-restricted funeral in Soweto’s Regina Mundi Catholic Church.

An award for courageous and outstanding journalism bears his name. He had left a legacy of courage in journalism and the pursuit of the truth that has yet to be recognized and acknowledged.

I have observed that of all sorts of insurance, health insurance is the most debatable because of the issue between the insurance company’s duty to remain profitable and the user’s need to have insurance plan. Insurance companies’ earnings on well being plans are certainly low, hence some providers struggle to gain profits. Thanks for the thoughts you share through this website.

Good post, I like reading about your holiday experience. The vacation amenities and comfort details were informative. Tips for making the most of a holiday will come in handy for my next trip. posts, include more information about the flight itinerary and the destinations visited. Keep up the good work, your post is informative and engaging.

Thank you for writing this post!

Impressive, this was such an informative article! I appreciated how you analyzed the topic and presented it in such concise manner. Your prose is captivating, and the case studies you used were extremely helpful. Thank you for publishing such a insightful article.

好吧,我真诚 享受 阅读它.您offered的这篇tip对于correct规划非常constructive.

I love reading a post that can make people think. Also, thanks for allowing me to comment!

Не теряйте времени и присоединяйтесь к нам уже сегодня.

I like that the website has

Очень полезно узнать о различных способах связи с потенциальными покупателями на доске объявлений.

I appreciate the option to filter ads based on distance, allowing me to find items within a specific radius of my location.

I like that the ads are sorted by date, so I can easily see the most recent listings.

great issues altogether, you simply gained a emblem new reader.

What might you suggest in regards to your put up that you just

made some days in the past? Any sure?

You actually make it seem so easy with your presentation but I find this

matter to be really something that I think I would never understand.

It seems too complex and very broad for me. I am looking forward

for your next post, I will try to get the hang of it!

Я рад, что наткнулся на эту статью. Она содержит уникальные идеи и интересные точки зрения, которые позволяют глубже понять рассматриваемую тему. Очень познавательно и вдохновляюще!

I know this if off topic but I’m looking into starting my own weblog

and was curious what all is needed to get setup? I’m assuming having a blog like

yours would cost a pretty penny? I’m not very internet

smart so I’m not 100% sure. Any tips or advice would be greatly appreciated.

Thank you

Appreciate the recommendation. Will try it out.

User-Friendly Interface: One of the standout features of CandyMail.org is its user-friendly interface. The platform is designed to be intuitive and easy to navigate, ensuring that users can seamlessly send and receive emails without any technical expertise. Whether you are a tech-savvy individual or a beginner, CandyMail.org caters to users of all levels of proficiency.

Очень понятная и информативная статья! Автор сумел объяснить сложные понятия простым и доступным языком, что помогло мне лучше усвоить материал. Огромное спасибо за такое ясное изложение!

Я хотел бы отметить глубину исследования, представленную в этой статье. Автор не только предоставил факты, но и провел анализ их влияния и последствий. Это действительно ценный и информативный материал!

Good 写了,I am website 的normal 访问者,维持 excellent 操作,It is 将成为 long 时间的常客.

Я впечатлен этой статьей! Она не только информативна, но и вдохновляющая. Мне понравился подход автора к обсуждению темы, и я узнал много нового. Огромное спасибо за такую интересную и полезную статью!

Очень интересная статья! Я был поражен ее актуальностью и глубиной исследования. Автор сумел объединить различные точки зрения и представить полную картину темы. Браво за такой информативный материал!

Я хотел бы выразить признательность автору этой статьи за его объективный подход к теме. Он представил разные точки зрения и аргументы, что позволило мне получить полное представление о рассматриваемой проблеме. Очень впечатляюще!

Статья представляет информацию о текущих событиях, описывая различные аспекты ситуации.

My programmer is trying to persuade me to move to .net from PHP.

I have always disliked the idea because of the expenses.

But he’s tryiong none the less. I’ve been using WordPress on a number of websites for about a

year and am concerned about switching to another platform.

I have heard fantastic things about blogengine.net.

Is there a way I can transfer all my wordpress content into

it? Any kind of help would be really appreciated!

Я прочитал эту статью с огромным интересом! Автор умело объединил факты, статистику и персональные истории, что делает ее настоящей находкой. Я получил много новых знаний и вдохновения. Браво!

This article is a goldmine of information. The author has covered all the important aspects of the topic and provided valuable insights that are hard to find elsewhere. I appreciate the clarity of explanations and the practical examples that make the content relatable. Well done!

The author explores potential areas for future research and investigation.

The information in this article is presented in a balanced and impartial manner.

Статья содержит разнообразные точки зрения, представленные в равной мере.

Автор старается сохранить нейтральность, чтобы читатели могли основываться на объективной информации при формировании своего мнения. Это сообщение отправлено с сайта https://ru.gototop.ee/

Автор статьи представляет информацию без предвзятости, предоставляя различные точки зрения и факты.

Автор статьи предоставляет разнообразные источники и мнения экспертов, не принимая определенную позицию.

Статья предлагает читателю возможность самостоятельно сформировать свое мнение на основе представленных аргументов.

Статья содержит анализ преимуществ и недостатков разных решений проблемы, помогая читателю принять информированное решение.

Статья охватывает различные аспекты обсуждаемой темы и представляет аргументы с обеих сторон.

Автор предлагает читателю дополнительные ресурсы для глубокого погружения в тему.

Эта статья – источник ценной информации! Я оцениваю глубину исследования и разнообразие рассматриваемых аспектов. Она действительно расширила мои знания и помогла мне лучше понять тему. Большое спасибо автору за такую качественную работу!

Статья содержит сбалансированный подход к теме и учитывает различные точки зрения.

Статья содержит актуальную статистику, что помогает оценить масштаб проблемы.

Статья содержит анализ причин и последствий проблемы, что позволяет лучше понять ее важность и сложность.

Автор предлагает разнообразные точки зрения на проблему, что помогает читателю получить обширное понимание ситуации.

Статья предлагает читателям широкий спектр информации, основанной на разных источниках.

The article is well-structured and flows smoothly.

Автор статьи представляет факты и аргументы, обеспечивая читателей нейтральной информацией для дальнейшего обсуждения и рассмотрения.

Я бы хотел выразить свою благодарность автору этой статьи за его профессионализм и преданность точности. Он предоставил достоверные факты и аргументированные выводы, что делает эту статью надежным источником информации.

Я благодарен автору этой статьи за его тщательное и глубокое исследование. Он представил информацию с большой детализацией и аргументацией, что делает эту статью надежным источником знаний. Очень впечатляющая работа!

This design is wicked! You definitely know how to keep a reader entertained. Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Great job. I really enjoyed what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it. Too cool!

I pay a visit every day some sites and websites to read articles, except this web site presents quality based content.

You have made some good points there. I looked

on the web for more information about the issue and found most people

will go along with your views on this site.

Hey there! I know this is somewhat off-topic but I

needed to ask. Does operating a well-established blog like yours take a massive amount

work? I’m completely new to operating a blog however I do write in my journal on a daily basis.

I’d like to start a blog so I can share my experience and thoughts online.

Please let me know if you have any kind of recommendations or tips

for new aspiring bloggers. Appreciate it!

It’s very straightforward to find out any matter on web as compared to books, as I found

this paragraph at this web page.

I’m now not certain where you’re getting your info, however good topic.

I must spend some time learning much more or figuring out more.

Thank you for wonderful info I was in search of this info for my mission.

I used to be able to find good info from your blog articles.

Prepare to be amazed by the digital products on this site. Take a sneak peek at https://nezacdigital.com/shop/

Level up while tipping girls in chat rooms and enjoy the BEST new live cam site experience https://cupidocam.com/content/tags/blonde

Thank you for sharing your info. I truly appreciate your efforts and I am waiting for your further post thank you

once again.

I’m extremely impressed together with your writing talents as neatly as with the layout in your

blog. Is this a paid subject matter or did you customize it your self?

Either way stay up the nice high quality writing, it is

uncommon to see a nice blog like this one nowadays..

Tremendous issues here. I am very happy to see your article.

Thanks so much and I am looking ahead to contact

you. Will you kindly drop me a mail?

Imaginary.cash – https://wiki.electroncash.de/wiki/Imaginary.cash

Good way of describing, and good piece of writing to take information on the topic of my presentation subject matter, which i am going to convey in university.

I am sure this post has touched all the internet users, its really really pleasant paragraph on building

up new website.

Sweet blog! I found it while surfing around on Yahoo News.

Do you have any tips on how to get listed in Yahoo News?

I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem

to get there! Cheers

I know this web site provides quality dependent

articles or reviews and other data, is there any other site

which presents such information in quality?

Hey I know this is off topic but I was wondering if you

knew of any widgets I could add to my blog that

automatically tweet my newest twitter updates.

I’ve been looking for a plug-in like this for quite some time and was hoping maybe you would have some experience with something like this.

Please let me know if you run into anything. I truly

enjoy reading your blog and I look forward to your

new updates.

Thanks a lot for sharing this with all folks you actually know

what you are talking about! Bookmarked. Please additionally seek advice from my website =).

We may have a link exchange arrangement between us

I simply could not depart your site prior to suggesting that

I extremely enjoyed the standard info a person supply on your visitors?

Is going to be back frequently to check up on new posts

I love what you guys are up too. Such clever work and coverage!

Keep up the awesome works guys I’ve added you guys to my own blogroll.

Greetings from Florida! I’m bored to tears at work so I decided to check out your site on my

iphone during lunch break. I enjoy the information you present here and can’t wait to

take a look when I get home. I’m surprised at how fast

your blog loaded on my cell phone .. I’m not even using WIFI, just 3G ..

Anyhow, good blog!

Interesting blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download

it from somewhere? A theme like yours with a few simple tweeks would really make my blog stand out.

Please let me know where you got your design. Appreciate it

magnificent publish, very informative. I ponder why the opposite specialists of this sector don’t understand this.

You should proceed your writing. I am sure,

you’ve a great readers’ base already!

Have you ever considered publishing an ebook or guest authoring on other blogs?

I have a blog centered on the same topics you discuss and would really like to have you share some stories/information. I

know my readers would enjoy your work. If you’re even remotely interested, feel free to send me an e mail.

This is really interesting, You’re a very skilled blogger.

I’ve joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your

excellent post. Also, I’ve shared your website in my social networks!

Do you have any video of that? I’d care to find out more details.

I was curious if you ever thought of changing the layout

of your site? Its very well written; I love what youve got to

say. But maybe you could a little more in the way of content so people could connect with it better.

Youve got an awful lot of text for only having one or 2 pictures.

Maybe you could space it out better?

Hi there! Someone in my Myspace group shared this site

with us so I came to check it out. I’m definitely enjoying the information. I’m

bookmarking and will be tweeting this to my followers!

Great blog and brilliant design and style.

I am no longer sure the place you are getting your information, however good topic.

I must spend a while studying much more or figuring out more.

Thanks for magnificent information I was looking for this information for my mission.

Useful info. Fortunate me I discovered your website by chance, and I’m shocked why this twist of fate didn’t took place earlier!

I bookmarked it.

Hello, this weekend is good designed for me, since this time i am reading this wonderful educational paragraph

here at my home.

Hi would you mind stating which blog platform

you’re working with? I’m looking to start my own blog in the near future but I’m having a tough

time selecting between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal.

The reason I ask is because your design and style seems different then most blogs and I’m

looking for something unique. P.S Sorry for getting off-topic but I had

to ask!

I constantly emailed this website post page to all my

contacts, since if like to read it then my contacts will too.

I don’t even know the way I ended up here, however I believed

this put up used to be good. I don’t recognise who you are however certainly you

are going to a famous blogger if you happen to are not already.

Cheers!

You’ve made some good points there. I checked on the

net for more info about the issue and found most people will go along with your views on this website.

What’s up, this weekend is pleasant in favor of me, since

this point in time i am reading this wonderful educational paragraph here at my

residence.

Excellent blog here! Also your site loads up fast! What host are you using?

Can I get your affiliate link to your host?

I wish my web site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

Hey would you mind letting me know which webhost

you’re working with? I’ve loaded your blog in 3 completely different web browsers and

I must say this blog loads a lot faster then most. Can you recommend a good internet hosting provider at a honest price?

Many thanks, I appreciate it!

I every time used to study piece of writing in news papers but now as I am a user of

web therefore from now I am using net for articles or reviews, thanks to web.

Cool blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it

from somewhere? A design like yours with a few simple tweeks would really make my

blog stand out. Please let me know where you got your theme.

Bless you

You really make it seem so easy along with your presentation but

I to find this topic to be actually something that I believe I might never understand.

It sort of feels too complicated and very extensive for me.

I am taking a look ahead to your next post, I’ll try

to get the cling of it!

Currently it looks like Drupal is the best blogging

platform out there right now. (from what I’ve read) Is that what you are using on your blog?

May I just say what a relief to discover someone

who truly knows what they’re discussing on the internet.

You actually realize how to bring a problem to light and make it important.

More and more people really need to check this out and understand this side of your story.

I was surprised that you are not more popular because you surely have the gift.

Yes! Finally something about Understanding male pattern baldness.

Hi! This post couldn’t be written any better! Reading this post reminds me

of my previous room mate! He always kept chatting about this.

I will forward this page to him. Pretty sure he will

have a good read. Many thanks for sharing!

Awesome post.

Nice weblog here! Also your web site so much up very fast! What web host are you the use of? Can I get your affiliate link on your host? I desire my website loaded up as quickly as yours lol my web page: Depi.lt

If some one needs to be updated with newest technologies then he must be pay a visit

this site and be up to date everyday.

Great information. Lucky me I came across your website by chance (stumbleupon).

I’ve book-marked it for later!

I pay a visit every day some web pages and blogs to read posts, except

this web site provides quality based articles.

Ms Sethi, Ayisha Diaz, The Fan Van ONLY FANS LEAKS ( https://picturesporno.com )

Nice weblog here! A big thank you for your blog article. Want more

Leighton Meester, Kristen Stewart, Emma Watson Nudes Leaks Only Fans ( https://UrbanCrocSpot.org/ )

Thanks on your marvelous posting! I actually enjoyed

reading it, you will be a great author.I will ensure

that I bookmark your blog and will often come back sometime soon. I want

to encourage continue your great writing,

have a nice evening!

Thank you for sharing your thoughts. I truly appreciate your efforts and I am waiting

for your further post thanks once again.

Hello Dear, are you actually visiting this web site daily, if so afterward you will absolutely

get pleasant know-how.

Your blog is a haven of positivity in a sometimes chaotic online world.

Hi there, all the time i used to check blog posts here in the early hours in the dawn, because i enjoy to learn more and more.

You’ve got incredible stuff listed here. [url=http://pr.lgubiz.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=1636055]decadron do kupienia w Krakowie[/url]

Simply just wished to emphasize I am relieved I stumbled in your website page. [url=http://aurasystem.kr/shp/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=353581]achat clonidine en Sénégal[/url]

Its like you read my mind! You seem to know so much about this, like you wrote the book in it or something. I think that you could do with some pics to drive the message home a bit, but other than that, this is great blog. A great read. I’ll definitely be back.

Terrific paintings! This is the type of information that are supposed to be shared around the net. Disgrace on Google for not positioning this post higher! Come on over and visit my site . Thank you =)

Open minded natural cam girls looking for her knight ! are you?

Exactly Feet Free Only Fans Leaks Mega Folder Link – https://crocspot.fun

Hi there this is somewhat of off topic but I was wondering if blogs use WYSIWYG editors or if you have to manually code with HTML.

I’m starting a blog soon but have no coding experience so I wanted to get guidance from someone with

experience. Any help would be enormously appreciated!

Автор предлагает читателю дополнительные материалы для глубокого изучения темы.

I have been exploring for a little for any high quality articles or blog posts in this kind of space . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this site. Studying this information So i抦 glad to show that I’ve a very just right uncanny feeling I found out just what I needed. I such a lot no doubt will make sure to do not disregard this site and provides it a glance regularly.

ven y disfruta de un momento agradable free live sex cams en tu tiempo libre

Thanks for the tips shared in your blog. Something also important I would like to say is that fat loss is not supposed to be about going on a dietary fads and trying to shed as much weight that you can in a couple of days. The most effective way to shed weight is by acquiring it slowly and using some basic recommendations which can provide help to make the most from the attempt to lose fat. You may be aware and already be following many of these tips, but reinforcing information never affects.

Hello there, simply turned into alert to your weblog through Google, and located that it is truly informative. I am going to be careful for brussels. I will be grateful should you proceed this in future. A lot of other folks will be benefited out of your writing. Cheers!

Hello there! This is kind of off topic but I need some guidance from an established blog. Is it very hard to set up your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out pretty quick. I’m thinking about setting up my own but I’m not sure where to start. Do you have any points or suggestions? Cheers

I have realized that over the course of creating a relationship with real estate proprietors, you’ll be able to come to understand that, in every real estate deal, a commission rate is paid. In the long run, FSBO sellers tend not to “save” the commission payment. Rather, they fight to earn the commission by means of doing the agent’s occupation. In doing so, they commit their money and time to perform, as best they will, the assignments of an broker. Those obligations include getting known the home by way of marketing, representing the home to willing buyers, creating a sense of buyer emergency in order to trigger an offer, scheduling home inspections, managing qualification inspections with the loan company, supervising repairs, and assisting the closing.

Great beat ! I would like to apprentice while you amend your site, how can i subscribe for a blog site? The account aided me a acceptable deal. I had been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast offered bright clear concept

Your webpage does not display correctly on my droid – you might wanna try and repair that

Another thing I’ve noticed is that often for many people, low credit score is the reaction of circumstances beyond their control. For example they may are already saddled by having an illness and as a consequence they have higher bills going to collections. It may be due to a occupation loss or maybe the inability to do the job. Sometimes divorce proceedings can really send the finances in the undesired direction. Thanks for sharing your ideas on this web site.

Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe: kamagra livraison 24h – vente de mГ©dicament en ligne

Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable https://kamagraenligne.com/# pharmacie en ligne fiable

pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance: pharmacie en ligne pas cher – pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es

I’m thoroughly captivated by your keen analysis and excellent ability to convey information. Your depth of knowledge shines through in every sentence. It’s obvious that you put a lot of effort into researching your topics, and that effort is well-appreciated. We appreciate your efforts in sharing such valuable insights. Keep up the great work! https://www.elevenviral.com

I’ve learned some important things through your post. I’d also like to say that there is a situation where you will apply for a loan and never need a co-signer such as a Federal government Student Aid Loan. In case you are getting that loan through a common banker then you need to be willing to have a co-signer ready to allow you to. The lenders will base their very own decision using a few variables but the main one will be your credit standing. There are some loan merchants that will as well look at your job history and decide based on that but in most cases it will depend on your scores.

doxycycline 25mg tablets [url=http://azithromycinca.com/#]buy tetracycline antibiotics[/url] price of doxycycline

get cheap clomid for sale: Clomiphene – can i order cheap clomid

prednisone: Steroid – cheapest prednisone no prescription

where to buy doxycycline online [url=https://azithromycinca.shop/#]doxycycline best price[/url] doxycycline prescription cost uk

can you buy zithromax online [url=https://amoxicillinca.shop/#]buy zithromax online[/url] zithromax online australia

buy prednisone from india: Deltasone – where to buy prednisone uk

amoxicillin 500mg capsule cost [url=https://doxycyclineca.com/#]cheapest amoxicillin[/url] cost of amoxicillin 30 capsules

prednisone 30: prednisone clomidca – how can i order prednisone

generic prednisone pills [url=http://clomidca.com/#]prednisone clomidca[/url] prednisone 50 mg coupon

zithromax generic price: zithromax – zithromax antibiotic

prednisone cost us [url=http://clomidca.com/#]clomidca[/url] prednisone best price

amoxicillin 500 mg price: buy cheapest antibiotics – azithromycin amoxicillin

average cost of generic zithromax [url=https://amoxicillinca.shop/#]buy zithromax amoxicillinca[/url] zithromax online paypal

where to buy doxycycline in australia: azithromycinca – doxycycline in usa

ampicillin amoxicillin [url=http://doxycyclineca.com/#]cheapest amoxicillin[/url] order amoxicillin online

how much is zithromax 250 mg: cheapest Azithromycin – zithromax 250 mg pill

zithromax capsules australia [url=https://amoxicillinca.com/#]cheapest Azithromycin[/url] how much is zithromax 250 mg

prednisone 40mg [url=https://clomidca.com/#]prednisone clomidca[/url] buying prednisone from canada

prednisone online pharmacy: clomidca – can i buy prednisone online without a prescription

cheap clomid no prescription [url=https://prednisonerxa.com/#]clomid[/url] where can i get generic clomid now

prednisone without rx: buy online – prednisone in india

can you buy generic clomid for sale [url=https://prednisonerxa.shop/#]cheap fertility drug[/url] can i order cheap clomid for sale

amoxicillin 500 mg brand name: amoxicillin – where can i buy amoxicillin over the counter

where to get generic clomid without rx [url=https://prednisonerxa.com/#]prednisonerxa.com[/url] buy clomid

where to buy amoxicillin pharmacy: amoxil best price – amoxicillin 500mg capsule

zithromax z-pak: zithromax – buy zithromax 1000mg online

clomid generic [url=https://prednisonerxa.com/#]clomid Prednisonerxa[/url] buying generic clomid no prescription

can you get clomid without insurance [url=https://prednisonerxa.com/#]Prednisonerxa[/url] how to buy cheap clomid prices

prednisone 10 mg over the counter: prednisone – buy prednisone without rx

buy amoxil [url=https://doxycyclineca.com/#]amoxil doxycyclineca[/url] amoxicillin 500mg price canada

buy 40 mg doxycycline: buy tetracycline antibiotics – buy doxycycline online australia

buy prednisone canada [url=https://clomidca.shop/#]Steroid[/url] prednisone 10mg

zithromax generic price: buy zithromax online – where to get zithromax

buying prednisone without prescription [url=http://clomidca.com/#]Steroid[/url] prednisone without prescription

doxycycline 100mg online uk: doxycycline – doxycycline price uk

can you get cheap clomid: clomid – where can i get cheap clomid without dr prescription

60 mg prednisone daily [url=https://clomidca.com/#]clomidca.com[/url] where to buy prednisone in canada

prednisone 40 mg rx [url=https://clomidca.shop/#]clomidca.com[/url] prednisone in canada

zithromax online: cheapest Azithromycin – buy zithromax without prescription online

buy generic zithromax no prescription [url=https://amoxicillinca.com/#]cheapest Azithromycin[/url] order zithromax over the counter

how to get clomid without insurance: Clomiphene – can i order generic clomid

buy amoxicillin 500mg capsules uk: amoxicillin – can you buy amoxicillin over the counter

prednisone 20 mg purchase: buy online – prednisone 20 tablet

zithromax azithromycin: Azithromycin – buy zithromax online cheap

buy doxycycline australia: doxycycline azithromycinca – where can i buy doxycycline in singapore

buy prednisone 5mg canada: prednisone clomidca – buying prednisone on line

prednisone 54: clomidca.shop – 200 mg prednisone daily

amoxicillin 500mg price: doxycyclineca – amoxicillin 500 mg capsule

amoxicillin medicine

Today, I went to the beach front with my children. I found a sea shell and gave it to my 4 year old daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She placed the shell to her ear and screamed. There was a hermit crab inside and it pinched her ear. She never wants to go back! LoL I know this is completely off topic but I had to tell someone!

I feel that is one of the most important info for me. And i’m glad reading your article. However wanna remark on some common issues, The web site style is perfect, the articles is truly excellent : D. Excellent job, cheers

https://autoinforme.com.br/banco-renault-lanca-cdb-para-pessoa-fisica/?replytocom=341326

I?ll immediately take hold of your rss feed as I can not to find your e-mail subscription link or newsletter service. Do you have any? Kindly let me recognize in order that I may just subscribe. Thanks.

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]northern doctors[/url] reputable mexican pharmacies online

purple pharmacy mexico price list [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]Mexico pharmacy that ship to usa[/url] mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

My partner and I stumbled over here different web address and thought I might check things out. I like what I see so i am just following you. Look forward to looking into your web page again.

buying prescription drugs in mexico online [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]Mexico pharmacy that ship to usa[/url] п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

When I initially commented I clicked the “Notify me when new comments are added” checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get several e-mails with the same comment. Is there any way you can remove me from that service? Thanks!

https://northern-doctors.org/# mexican mail order pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]mexican pharmacy[/url] mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]Mexico pharmacy that ship to usa[/url] buying prescription drugs in mexico online

buying prescription drugs in mexico online [url=http://northern-doctors.org/#]mexican pharmacy online[/url] reputable mexican pharmacies online

buying prescription drugs in mexico online [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]mexican northern doctors[/url] mexican rx online

https://northern-doctors.org/# mexican rx online

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]northern doctors pharmacy[/url] reputable mexican pharmacies online

I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you create this website yourself or did you hire someone to do it for you? Plz reply as I’m looking to construct my own blog and would like to know where u got this from. kudos

What’s up to all, how is everything, I think every one is getting more from this web page, and your views are nice designed for new visitors.

Magnificent goods from you, man. I’ve understand your stuff previous to and you are just too excellent. I actually like what you’ve acquired here, really like what you’re saying and the way in which you say it. You make it entertaining and you still care for to keep it wise. I cant wait to read much more from you. This is really a wonderful website.

reputable mexican pharmacies online

http://cmqpharma.com/# purple pharmacy mexico price list

purple pharmacy mexico price list

Информационная статья представляет различные аргументы и контекст в отношении обсуждаемой темы.

Hey there, You have done an incredible job. I will definitely digg it and personally recommend to my friends. I am confident they will be benefited from this site.

This info is worth everyone’s attention. How can I find out more?

It’s going to be end of mine day, except before end I am reading this fantastic article to improve my know-how.

This design is incredible! You certainly know how to keep a reader amused. Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Excellent job. I really enjoyed what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it. Too cool!

A person essentially help to make seriously posts I would state. This is the first time I frequented your website page and thus far? I amazed with the research you made to make this particular publish amazing. Magnificent job!

Thank you for the good writeup. It in fact was a amusement account it. Look advanced to more added agreeable from you! By the way, how could we communicate?

I all the time emailed this webpage post page to all my associates, because if like to read it then my friends will too.

An impressive share, I simply given this onto a colleague who was doing a little evaluation on this. And he the truth is purchased me breakfast as a result of I found it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the deal with! But yeah Thnkx for spending the time to discuss this, I feel strongly about it and love reading extra on this topic. If potential, as you turn out to be expertise, would you thoughts updating your blog with extra details? It’s highly useful for me. Huge thumb up for this weblog submit!

I discovered your blog website on google and check just a few of your early posts. Proceed to maintain up the superb operate. I simply further up your RSS feed to my MSN Information Reader. Searching for ahead to reading more from you afterward!?

My brother recommended I would possibly like this web site. He was once totally right. This post actually made my day. You can not believe just how a lot time I had spent for this information! Thank you!

At this time it seems like WordPress is the top blogging platform available right now. (from what I’ve read) Is that what you are using on your blog?

Автор статьи представляет информацию с акцентом на факты и статистику, не высказывая предпочтений.

Hey there just wanted to give you a brief heads up and let you know a few of the pictures aren’t loading correctly. I’m not sure why but I think its a linking issue. I’ve tried it in two different internet browsers and both show the same results.

Thanks for your valuable post. Over time, I have come to understand that the actual symptoms of mesothelioma are caused by the actual build up connected fluid between the lining of the lung and the torso cavity. The condition may start within the chest area and distribute to other areas of the body. Other symptoms of pleural mesothelioma include losing weight, severe inhaling trouble, throwing up, difficulty swallowing, and puffiness of the face and neck areas. It should be noted that some people living with the disease never experience almost any serious signs or symptoms at all.

Thanks, I have recently been hunting for facts about this subject matter for ages and yours is the best I’ve found so far.

Hi there, just was alert to your weblog thru Google, and located that it’s truly informative. I am gonna watch out for brussels. I will appreciate for those who continue this in future. A lot of other folks will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

Wow! This blog looks exactly like my old one! It’s on a entirely different subject but it has pretty much the same layout and design. Outstanding choice of colors!

Я просто не могу пройти мимо этой статьи без оставления положительного комментария. Она является настоящим примером качественной журналистики и глубокого исследования. Очень впечатляюще!

It?s really a cool and helpful piece of info. I?m glad that you simply shared this useful information with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

Полезная информация для тех, кто стремится получить всестороннее представление.

Hi there, I discovered your website by means of Google whilst looking for a comparable subject, your site got here up, it looks great. I have bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

Автор старается быть нейтральным, чтобы читатели могли самостоятельно рассмотреть различные аспекты темы.

Thanks on your marvelous posting! I actually enjoyed reading it, you may be a great author. I will be sure to bookmark your blog and will often come back later in life. I want to encourage that you continue your great work, have a nice weekend!

I have learned some new items from your internet site about computer systems. Another thing I’ve always imagined is that laptop computers have become a product that each family must have for many people reasons. They provide convenient ways in which to organize homes, pay bills, go shopping, study, tune in to music and in many cases watch shows. An innovative method to complete all of these tasks is with a laptop. These computers are mobile, small, strong and convenient.

Статья предлагает широкий обзор событий и фактов, связанных с обсуждаемой темой.

One other thing I would like to mention is that rather than trying to fit all your online degree classes on days of the week that you finish off work (because most people are tired when they get back), try to obtain most of your sessions on the week-ends and only a couple of courses on weekdays, even if it means a little time away from your saturday and sunday. This pays off because on the saturdays and sundays, you will be more rested and concentrated on school work. Many thanks for the different recommendations I have realized from your web site.

Greate article. Keep writing such kind of information on your site. Im really impressed by it.

Porn site

Porn site

Porn site

Pornstar

Porn site

Scam

Viagra

Porn

Статья содержит ясные и убедительные аргументы, подкрепленные конкретными примерами.

Viagra

Buy Drugs

Viagra

Buy Drugs

Porn

Porn

Porn

Sex

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies [url=http://foruspharma.com/#]п»їbest mexican online pharmacies[/url] medication from mexico pharmacy

https://indiapharmast.com/# online shopping pharmacy india

Sex

india pharmacy [url=http://indiapharmast.com/#]buy prescription drugs from india[/url] п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

http://indiapharmast.com/# best online pharmacy india

Buy Drugs

Sex

Мне понравился четкий и структурированный стиль изложения в статье.

I’m amazed by the quality of this content! The author has obviously put a huge amount of effort into exploring and arranging the information. It’s refreshing to come across an article that not only offers helpful information but also keeps the readers engaged from start to finish. Great job to her for making such a remarkable piece!

buying from online mexican pharmacy [url=https://foruspharma.com/#]mexican pharmacy[/url] mexican pharmacy

Buy Drugs

Porn site

Статья представляет обширный обзор темы и учитывает ее исторический контекст.

paxlovid for sale: paxlovid buy – paxlovid price

http://ciprodelivery.pro/# ciprofloxacin over the counter

Scam

Мне понравился объективный подход автора, который не пытается убедить читателя в своей точке зрения.

Porn

buy ciprofloxacin over the counter: buy cipro without rx – antibiotics cipro

Buy Drugs

Buy Drugs

Thanks for the helpful write-up. It is also my belief that mesothelioma has an incredibly long latency interval, which means that signs of the disease would possibly not emerge till 30 to 50 years after the preliminary exposure to mesothelioma. Pleural mesothelioma, and that is the most common sort and has an effect on the area about the lungs, could potentially cause shortness of breath, torso pains, including a persistent coughing, which may cause coughing up bloodstream.

Scam

http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline india cost

Sex

buy clomid without rx: can i buy cheap clomid online – clomid without dr prescription

Scam

Viagra

buy paxlovid online: paxlovid india – paxlovid generic

Buy Drugs

Porn

Pornstar

amoxicillin 775 mg: buying amoxicillin online – amoxicillin from canada

Scam

Это помогает создать обстановку для объективного обсуждения.

Эта статья является настоящим сокровищем информации. Я был приятно удивлен ее глубиной и разнообразием подходов к рассматриваемой теме. Спасибо автору за такой тщательный анализ и интересные факты!

Thanks for sharing your info. I really appreciate your efforts and I am waiting for your next write ups thank you once again.

Wohh precisely what I was searching for, regards for putting up.

My website: анал порно

Porn site