[intro]Khehla Chepape Makgato has dug deep into his creative talent to produce art works that remind people of the “historical injustice that was Marikana”. [/intro]

We are all haunted by the facts and the images have been burned into our collective memory. The 34 striking miners who were gunned down on 16 August 2012 by those who dedicated their lives to ‘protect and serve’. Hunted and murdered by the South African police, the death of the low-wage miners shook the world and took us back to a time when state violence against the black population was the order of the day.

Khehla Chepape Makgato’s third solo exhibition is titled Mephaso: The Rituals and interprets the still fresh wounds of the killings. The exhibition is held amid the release of the Marikana report by President Jacob Zuma, and alongside the Marikana residents calling for the koppie, where the protesters gathered on that fateful day, to be declared a heritage site. Makgato’s artworks are being displayed at the Michaelis Art Library in Johannesburg.

“That was a historical injustice and I felt that I need to talk about it until someone hears. Until the government hears. Even if the government does not heed the call now, as long as I engage and involve the young people, they will grow up to their positions of leadership knowing that there was an incident that happened that shocked the world.”

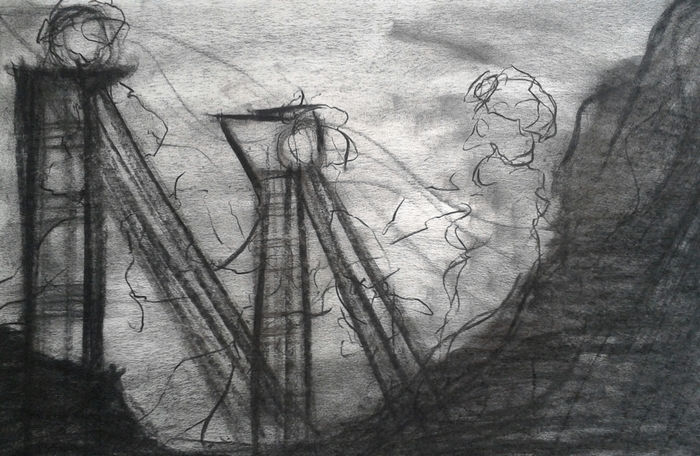

The charcoal drawings and collages narrate his interpretation of the shocking events that took place three years ago. With the massacre forming a strong part of our national heritage, his work is a continuation of our public mourning for the protestors who paid the ultimate price, and is a personal tribute to the fallen workers.

Kanyanaya Moepong, Charcoal and Pastel, 65x70cm, 2015

“My main concern is to get people talking about it. I want to exhibit a decade of Marikana tackling it from different angles because if I do not become an active citizen and tell the stories about our country, somebody will come and tell these stories about us, while we fold our arms,” said Makgato.

“Biko once said you are not free until you can tell your own story; and so in the process of telling the Marikana story I’m yearning to be free and the more I tell this story the more free I become”.

Makgato has held two previous solo exhibitions; each one dedicated to the Marikana Massacre. The name of his current exhibition, Mephaso, translates to the traditional ceremony of laying souls to rest in Sepedi. His works visually references the customs that come with death, mourning, healing and memory.

“The use of the animals, especially goats, is very important,” he said. “Goats are used as mediums to communicate with the ancestors…to ask for blessings or prevent bad luck. If a person passes on away from their home, for instance, a ritual takes place where the goat will be carefully prepared to take the spirit of the departed soul to his final resting place, with his ancestors. Before this preparation, a knowledgeable elder will burn a traditional herb called ‘Meshinkwane’ or ‘Impepho,’ a herb used to communicate with the ancestors.”

Mokgalo (Buffalo Thorn) II, Charcoal and Pastel, 65x70cm, 2015

Some of his charcoal drawings include the Buffalo Thorn tree, usually symbolic of the burial of a chief.

“When a chief dies and they bury him they plant the Buffalo Thorn tree on top of his grave to remind the generations after that a chief was buried there. There are so many beliefs around this tree. It has two thorns: one faces back, one faces forward. It is believed to be a direction from the past to the future. The one that is facing forward, indicates the future and the one facing backwards represents the history of the people”.

He dedicates the show to the “untold stories, the unheard voice and the voices of our African cultures and belief systems”.

Orphan III, Paper Construction, 60 x 50cm, 2014

Born in Kensington, Johannesburg, and raised in a village just outside Polokwane, Limpopo, Makgato studied printmaking at Artist Proof Studio in Newtown, Johannesburg in 2009. Since graduating in 2012 he’s participated in a range of community art projects and international exchange programmes.

The multi-talented artist also studied journalism, and is currently pursuing a degree in African art history, and theatre and drama practices through correspondence. However, his first love is art, a tough road for any young, black South African. 2008, saw him move to Johannesburg to pursue his art career with little resources or support from his family back home.

“My mother wanted me to go and work because she thought art would not do anything for me. I went for interviews and I got jobs, but I knew in my heart that I wanted to pursue art and literature”.

At the time he called his mother and brother telling them that he had found a job but rejected it, “I said that I’m not going back [to work] and my brother was very difficult about it. He said I should never turn to him when a situation gets tougher as I neglected the job he helped me to get and I agreed.”

During his first year of art school Makagato lived in Marlven and walked to and from art college in Newtown, which took him an hour and a half each way. “I was walking three hours a day and I didn’t have money to buy lunch. So everything was on my own. I would come back home at night and have something to eat. So it was those sacrifices that got me to where I am today.”

During his second year at art school he worked as a studio intern for David Krut Art Resources, which allowed him to “participate in printmaking projects with visiting artists”. This is around the time he met William Kentridge, who later become his mentor.

His first solo exhibition, titled Marikana: Truth, Probability and Paradox was paid for from his own pocket and looked at the concept of labour and migration. It sought to investigate and interrogate labour relations and inequality in South Africa. None of the galleries he approached showed interest in his work; and so he decided to curate his own art but could not afford to frame his work.

Orphan II, Paper Construction, 60x50cm, 2014

“I fought with a small gallery before I went solo and started doing everything on my own. That’s when I took up the responsibilty of being a curator. In my first show I didn’t even have frames. In my second solo show I used old frames to frame my work. I had no choice but to do it from my pocket with the little amount of money that I have. So it’s those things that we do to take back power. I took control over my own process.”

Makgato says that black artists have a double burden to bear. With the perception of their families and community on one hand, and the privileged, largely commercial galleries on the other; which he says are ‘hostile’ and at times are unwelcoming to young, emerging black artists.

“At the talks and panels they talk to you like you’re nothing and it’s because we allow it. As long as we allow them to treat us like this the longer they will continue to be arrogant and aggressive. But if we put a stop to it, this means we need to tell our own stories and curate our own shows and have a black owned art publication that covers all the art practitioners equally.”

The traditional gallery space has been a contentious issue, especially when it comes to who can and who cannot access the space. Makgato says that this influences whether black communities and audiences are able to access and enjoy the arts, and this influences whether they believe art to be a viable career path for their children.

“I have experienced art practitioners blaming black communities about not collecting art or going to art galleries. But we cannot drive crowds into galleries without being concerned about how we create something on paper that can make it easy for people to read and understand, which will ultimately drive them to the galleries.”

“They know what art is about but they cant access it. Most of our people don’t feel like they belong in that space. We are not thinking about our audience, we’re blaming them that they do not support the arts. Who goes to commercial galleries? Mostly art collectors and art practitioners. So it means that we’re doing art for privileged commercial galleries and we’re giving them the authority to dictate our message and our art.”

This is one of the reasons Makgato decided to hold his exhibition at a library in the centre of the bustling Johannesburg city as opposed to an art gallery, so that the public can interact with his art.

“Taking art to the public means taking it to the churches, or to the community halls, to the library. I also wanted to take our people to the library, even if they’re not going there to read, even if they’re going there to see my show, I’ve managed to drive them into the library. Next time they pass the library they’ll be familiar with it and they’ll remember my work. So next time they have time they can go in and walk around and take out books. My mission is to take people to the theatre, to the art gallery, to the museum, to the library, the very places that were denied to us”.

It’s been a tough journey for the young artist, and this is only the beginning.

“We’re coming from a black community background where studying art is frowned upon and this still persists because when you do art you’re regarded as someone who is lazy, someone who cannot think, you’re just wasting time. So as black art practitioners we have a lot of work to do to say art is a profession and you can make a living out of it.”

He repeated his earlier assertion: “My main objective is to have some of my time and energy focused on Marikana because that was a historical injustice and I felt that I need to talk about it until someone hears. Until the government hears. Even if the government does not heed the call now, as long as I engage and involve the young people who will be the leaders of tomorrow, they will grow up to their positions of leadership in their sectors knowing there was an incident that happened that shocked the world.”

Mephaso: The Rituals is showing at the Michaelis Art Library in Central Johannesburg (Corner Sauer and President Street) until the end of September

шлюхи в иркутске

This paragraph offers clear idea designed for the new

users of blogging, that really how to do blogging.

As the admin of this website is working, no doubt very soon it

will be renowned, due to its feature contents.

Yes! Finally someone writes about website.

Hi Dear, are you in fact visiting this web site daily,

if so then you will without doubt obtain nice experience.

Appreciating the persistence you put into your site and detailed information you offer.

It’s great to come across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the same unwanted rehashed material.

Excellent read! I’ve saved your site and I’m including your

RSS feeds to my Google account.

Undeniably believe that which you stated. Your favorite justification seemed to be on the web the simplest thing to be

aware of. I say to you, I definitely get irked while people consider worries

that they plainly don’t know about. You managed to hit the nail upon the top and defined out the

whole thing without having side-effects , people can take

a signal. Will likely be back to get more.

Thanks

I lately had the plrasure of working woth HireHer ffor sourcing Mobile Engineers for our organisation,

and I have to say, I was thoroughly impressed with their service.

Stop by my blog post – 미수다

Yoou can support cleqn up at private homes or

businesses, such as hospitals orr hotels.

Feel free to visit my web-site … 룸싸롱 알바

Next in the list of highest paying jobs in India has to be an AI professional.

Also visit my site; 다방 알바

It’s a form of passive income that can make you upp tto $50,000+ per

month.

My webpage – 미수다알바

I could not resist commenting. Exceptionally well written!

Keep on writing, great job!

My brother recommended I may like this blog. He used to be entirely right.

This post truly made my day. You can not imagine simply how

so much time I had spent for this info! Thanks!

I am in fact grateful to the holder of this site who has shared this great

article at at this place.

May I simply say what a relief to uncover somebody

who truly knows what they are discussing over the internet.

You certainly know how to bring a problem to

light and make it important. More and more people ought to read this and

understand this side of your story. I was surprised that

you are not more popular since you definitely have the gift.

Hello, yeah this paragraph is in fact nice and I

have learned lot of things from it about blogging. thanks.

I was wondering if you ever thought of changing the structure of your

blog? Its very well written; I love what youve got to say.

But maybe you could a little more in the way of content so people could connect with it better.

Youve got an awful lot of text for only having 1 or two images.

Maybe you could space it out better?

Very energetic blog, I liked that a lot. Will there be a part 2?

My partner and I stumbled over here by a different web page and thought

I might as well check things out. I like what I

see so now i am following you. Look forward to looking at your web

page repeatedly.

It’s an remarkable paragraph in support of all the web visitors; they

will take advantage from it I am sure.

Its like you read my mind! You appear to know so much about this, like you wrote the book in it or something.

I think that you could do with a few pics to drive the

message home a bit, but instead of that, this is wonderful blog.

A great read. I will certainly be back.

I do believe all of the ideas you’ve offered on your post.

They’re really convincing and will definitely work.

Still, the posts are very quick for novices. May just you please extend them a little from subsequent time?

Thanks for the post.

Hi to every one, the contents existing at this site are

truly amazing for people knowledge, well, keep up the good work fellows.

Link exchange is nothing else but it is only placing the other person’s webpage

link on your page at proper place and other person will also do same for you.

If some one desires to be updated with most up-to-date technologies

after that he must be visit this web page and be up to date all the time.

Oh my goodness! a wonderful article dude. Thanks a ton Nevertheless We are experiencing problem with ur rss . Don’t know why Struggle to register for it. Possibly there is anyone finding identical rss problem? Anybody who knows kindly respond. Thnkx

That very first sold me about this viewpoint to deal with something that provides a crucial description respecting ?

I precisely wished to say thanks again. I do not know the things I would have taken care of without the entire solutions provided by you relating to this situation. It was the distressing circumstance in my view, but viewing your specialised style you dealt with the issue made me to cry with contentment. Now i am happier for the assistance as well as believe you are aware of a powerful job you happen to be getting into training men and women thru a web site. I’m certain you haven’t encountered any of us.

Gucci Handbags Have you investigated adding some videos for your article? It will truly enhance my understanding

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read something such as this before. So nice to find somebody with authentic applying for grants this subject. realy thank you for starting this up. this web site is something that’s needed on the net, somebody with a bit of bit originality. helpful task for bringing something totally new towards web!

we would usually buy our bedroom sets from the local retailer which also offers free delivery.

It seems you are getting quite a lof of unwanted comments. Maybe you should look into a solution for that. Have a nice day!

Hello! I just want to supply a massive thumbs up to the wonderful information you’ve here for this post. I’ll be returning to your blog post for additional soon.

You produced some decent points there. I looked on the internet for the problem and discovered most individuals go in addition to with all your website.

When I originally commented I clicked the -Notify me when new surveys are added- checkbox and already each time a comment is added I purchase four emails with the same comment. Will there be any way you may get rid of me from that service? Thanks!

Proper supplementation is necessary to get the body you want! Check out my supplement advice here!

Hi there to every one, it’s in fact a nice for me to go to see this web page, it includes important Information.

Wow that was odd. I just wrote an extremely long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear.

Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Anyway, just wanted to say excellent blog!

Hi there Dear, are you genuinely visiting this website on a

regular basis, if so afterward you will definitely get nice knowledge.

Very energetic post, I enjoyed that a lot. Will there be a part 2?

Fantastic blog! Do you have any recommendations for aspiring writers?

I’m planning to start my own blog soon but I’m a little lost on everything.

Would you suggest starting with a free platform like WordPress

or go for a paid option? There are so many

choices out there that I’m completely confused ..

Any tips? Kudos!

Feel free to visit my web blog – vpn special coupon

I’m not sure why but this website is loading extremely slow for me.

Is anyone else having this issue or is it a issue on my end?

I’ll check back later on and see if the problem still exists.

Here is my blog vpn special coupon code 2024

Today, I went to the beach with my children. I found a sea shell and gave it

to my 4 year old daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She placed the shell

to her ear and screamed. There was a hermit crab inside and it

pinched her ear. She never wants to go back! LoL I know this

is totally off topic but I had to tell someone!

My blog – vpn special coupon code 2024

Wow, marvelous blog layout! How lengthy have you been blogging for?

you made running a blog glance easy. The overall look of your web

site is wonderful, let alone the content! You can see

similar here ecommerce

The models here are usually carefully selected professional models, and there are many specialized hot cam show, so you can be sure to have an exciting session.

What抯 Happening i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve found It positively useful and it has helped me out loads. I hope to contribute & aid other users like its helped me. Great job.

I know this if off topic but I’m looking into starting my own blog and was curious what all is required facebook vs eharmony to find love online

get setup? I’m assuming having a blog like yours would cost

a pretty penny? I’m not very internet smart so I’m not 100% sure.

Any recommendations or advice would be greatly appreciated.

Cheers

I expect that Heads of Free cam girls and Teachers will enable and motivate students to utilize this material during zero periods, extra classes and regular classes

I have learn several excellent stuff here. Definitely value bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how much effort you place to create one of these excellent informative site.

Hey There. I discovered your blog the use of msn. That is a really neatly written article. I抣l make sure to bookmark it and return to learn extra of your useful information. Thanks for the post. I抣l definitely return.

you’re actually a just right webmaster. The web site loading velocity is

incredible. It sort of feels that you’re doing any distinctive

trick. Moreover, The contents are masterpiece.

you’ve performed a wonderful job on this matter!

Feel free to visit my page :: eharmony special coupon code 2024

Article writing is also a excitement, if you know then you can write

if not it is complex to write.

Feel free to visit my blog – nordvpn special coupon code

hello there and thank you for your info ?I抳e definitely picked up something new from right here. I did however expertise some technical issues using this site, as I experienced to reload the site a lot of times previous to I could get it to load correctly. I had been wondering if your hosting is OK? Not that I am complaining, but slow loading instances times will very frequently affect your placement in google and could damage your high-quality score if advertising and marketing with Adwords. Anyway I am adding this RSS to my email and could look out for much more of your respective interesting content. Make sure you update this again very soon..

Cute eastern free online live webcams, squirt, toys, DP, outfits, RP

amoxicillin generic: amoxil – amoxicillin medicine over the counter

amoxicillin 875 125 mg tab

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]mexican pharmacy online[/url] mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]mexican pharmacy northern doctors[/url] mexico drug stores pharmacies

https://northern-doctors.org/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]mexican pharmacy northern doctors[/url] pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

buying prescription drugs in mexico: mexican pharmacy northern doctors – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

mexican pharmacy: Mexico pharmacy that ship to usa – best online pharmacies in mexico

buying prescription drugs in mexico [url=http://northern-doctors.org/#]mexican pharmacy northern doctors[/url] mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

purple pharmacy mexico price list [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]Mexico pharmacy that ship to usa[/url] п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

mexican mail order pharmacies: mexican pharmacy – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

medicine in mexico pharmacies: mexican pharmacy online – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]mexican pharmacy[/url] mexican rx online

medicine in mexico pharmacies [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]northern doctors pharmacy[/url] mexican drugstore online

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]mexican pharmacy northern doctors[/url] mexican pharmaceuticals online

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

https://cmqpharma.com/# п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

mexican drugstore online

canadian online drugs: best canadian pharmacy to buy from – trusted canadian pharmacy

https://canadapharmast.com/# legit canadian online pharmacy

canadian pharmacies that deliver to the us [url=http://canadapharmast.com/#]legal canadian pharmacy online[/url] reputable canadian online pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=https://foruspharma.com/#]mexican pharmaceuticals online[/url] buying prescription drugs in mexico online

http://indiapharmast.com/# cheapest online pharmacy india

indian pharmacy online [url=http://indiapharmast.com/#]online pharmacy india[/url] indian pharmacy paypal

http://canadapharmast.com/# canadian pharmacy 1 internet online drugstore

can you buy clomid without a prescription: can i order generic clomid tablets – can i buy clomid

https://amoxildelivery.pro/# amoxicillin pharmacy price

doxycycline 1000 mg best buy [url=http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/#]where can i get doxycycline online[/url] doxycycline 50

where to get clomid without rx: order generic clomid pills – clomid tablets

cheap clomid prices: how to get generic clomid pills – can you buy clomid

price of doxycycline: online doxycycline prescription – buy doxycycline monohydrate

п»їcipro generic: buy generic ciprofloxacin – cipro for sale

price of amoxicillin without insurance: amoxicillin pharmacy price – how to buy amoxycillin

paxlovid price: п»їpaxlovid – paxlovid pill