Go in with something to say and say it — irrespective of the question. You can always say ‘that’s not the real question’ and then ask the one you want to ask.

Anima n. (Jung’s psychol.) A figure symbolizing the feminine aspect of the human psyche

Animus n. animosity, hostility, (Jung’s psychol.) a figure symbolizing the masculine aspect of the human psyche

Any reasonably experienced and competent journalist can interview. Right?

All you have to do is find the interviewee, shove a microphone in the face, ask some questions roughly on the subject matter and get the hell out.

Off to the next interview.

It’s easy. After all, you have huge built-in advantages:

- If you and the interviewee agree on nothing else in all of life, you’re soul-mates on the fact that you both want to do the best interview that’s humanly possible. You both want to look good. So you and the interviewee are on the same side.

- You’re in charge of the interview. It’s your territory, your camera and your microphone.

- The interviewee has agreed to take part in the interview.

- The interviewee is talking about the most fascinating subject in all the world — her or himself.

- Most of us really want to talk about things that matter to us.

- All of us want to persuade others of our most insightful truths.

So interviewing should be easy.

Animus Interviewing

Animus-interviewing is easy. You create two distinct, diametrically opposed, sides. The interviewer and the interviewee. Two solitudes. From the dominant solitude (after all, it’s your territory, your camera, your microphone), you as the interviewer interrogate the interviewee.

But interrogating produces lousy interviews. (Unless it’s that rare 60 Minutes kind of interview which climaxes when you pull out the pictures and ask “Can you deny that this is you with the Bulgarian stripper triplets on the nude beach in Jamaica?”)

Interrogating makes people rationalize. Makes them justify their behavior. And when people justify they close up, drop the portcullis down, fill the moat with crocodiles and pour boiling oil on visitors.

They automatically rationalize that whatever they’re being questioned about was the right thing for them to do, under the circumstances, at the time.

They go into protection-mode. Like tortoises. They’ll answer, but they won’t explore, won’t search inside. They won’t give anything of themselves. Certainly, they almost never confess.

They might be technically accurate in their answers. But they certainly won’t be open and honest.

So nothing happens in your average Animus-interview except avoidance. No light. No bringing of understanding. No human emotion. No exploring the human condition. No click of recognition for the viewer.

You’ve seen ten thousand Animus-interviews like this. It’s the norm. It’s the way it’s done.

The Animus-interviewer — the unhuman interrogator — usually chooses, quite deliberately, a like-minded, unhuman Animus-interviewee. Almost always it’s a bureaucratic spokesman (almost always male), a representative of some institution or organization who, because of his position, is supposed to be an expert.

(In John le Carré’s book The Russia House, Professor Yakov Savelyev warns about such people:

“Experts are addicts. They solve nothing. They are servants of whatever system hires them. They perpetuate it. When we are tortured, we shall be tortured by experts. When we are hanged, experts will hang us. When the world is destroyed, it will be destroyed not by its madmen but by the sanity of its experts and the superior ignorance of its bureaucrats.”)

No Click of Recognition

Animus-interviewers cherish experts and bureaucrats and spokesmen and representatives of institutions and organizations. They keep their names and coordinates on their smartphones at all times.

That’s because experts and bureaucrats and spokesmen and representatives of institutions and organizations give reasonable, rational, sensible answers in 10-second segments at the drop of a lens cap.

They know what’s wanted. They know how to behave. They don’t confuse emotion with fact or the other way round. They don’t get mad when interrupted by the interviewer. As Sir Humphrey would say, they’re sound. Very sound. Or, his highest compliment, “they’re one of us”.

There’s a small problem, however. If you interview experts and bureaucrats and spokesmen and representatives of institutions and organizations it’s hard to get answers with any real and human meaning.

By the very nature of their profession, these people have nothing to say to touch the viewer. Nothing to bring that click of recognition that says “we share a common humanity.” Nothing to illuminate the exciting and dangerous world of human emotion.

That’s because experts and bureaucrats and spokesmen and representatives of institutions and organizations have nothing to be human or emotional about. Except pleasing whoever signs the cheques.

They’re observers. They don’t represent themselves. They represent other people.

They aren’t participants. They don’t take part.

All they can do is tell you what other people pay them to say.

Doesn’t have to be true, of course.

You can interrogate them as much as you want. But, mostly, nothing happens to — or for — the viewer. From the Animus-interviewer’s point of view, however, they give great, safe, lucid, professional interview. So everyone looks good.

Sometimes Animus-interviewers go so far as to turn perfectly legitimate participants — human beings — into experts and spokespeople and representatives of institutions and organizations.

Which is a terrible thing to do.

And should be severely punished.

Jock Journalism

Ron Lancaster the famous Canadian quarterback.

Sports interviewing is worst of all.But, in fact, it’s merely the average news interview taken to extreme.

I’m running an interview workshop for sports reporters. At the end of the workshop I go out for a beer with Ron Lancaster, one of Canadian football’s most famous quarterbacks.

I ask Lancaster how many times he’s been interviewed.

“Thousands of times.”

“How many times have you been interviewed well?

He thinks. “Only once.”

He explains that he learned very early in his career that he can say anything he wants in an interview. Reporters have no interest in the truth. Or him as a human being. Mostly, the reporters just want to make statements about the game and/or the team and have him agree. So they — the reporters — look good.

The typical reporter’s question went something like (as I recall it today) “… so the turning point for the team came half-way in the third quarter … you dropped back … couldn’t complete the Running-Dog Reverse Red Inaudible … you considered, just for a moment the Lonesome Polecat … or even the Hail Mary … but that wouldn’t work … so you scrambled, lateralled to the nose guard and broke the game wide open …”

Lancaster grins. “What the hell am I expected to say to that sort of question? It just seemed easier to agree. So I agreed.”

Then what was his one good interview about?

“It came from a reporter who’d done his homework. He asked me a question about the one thing I care most about. Not football. My family. He asked me how my family — particularly my young son — handled seeing me beaten up by monsters every weekend. So I told him. It wasn’t easy and I got very emotional about it. It was the only good interview I ever gave.”

It was, of course, an Anima-interview. Not necessarily because of its subject matter. But because the reporter bothered to ask a human being a human question.

Seek And Ye Shall Find (Sometimes)

It’s occasionally possible to turn experts and spokespeople into participants in the story. To get them to talk on the personal, rather than the institutional level.

Sometimes, somewhere, lurking hidden under even the most institutional of experts and spokespeople, it’s occasionally possible to find a human being.

For instance. You’re interviewing the Minister of Agriculture about a proposed new farm bill. You ask the conventional Animus-reporter’s question like:

“How will the proposed new bill effect the socio-economic status of the agricultural sector — which is already petitioning against having quota exports to the European Community halved by the end of this quarter and has seen net profits fall by 22% over the trimester?”

No. No. No.

An interviewee almost always answers in the same language as the question is asked.

If you ask institutional, coded, power-speak questions you get institutional, coded power-speak answers.

Try this instead:

“I talked to this farmer, Fred Nurk, who works 500 acres of corn outside Maritzburg. Good farmer. He reckons the new bill could push him right over the edge. Might even have to sell the farm. What can you tell Fred about the new bill?”

There’s a chance — just a chance — that you might get a human answer. It doesn’t always work, of course. But when it does, you get an answer that means something. Even enlightens the viewer.

Of course, it’s an Anima-question.

Anima Interviewing

One of the differences between Animus-interviewing and Anima-interviewing is that the Animus-interview relies on confrontation and conflict to get answers, while the Anima-interview uses cooperation and collaboration.

In fact, in the Anima-interview the roles of the interviewer and interviewee are pretty much complementary.

Which means you have to work a lot harder.

In the Anima-interview:

- The interviewer’s job is to persuade, guide and help the interviewee to tell what happened — and what it means — from the emotional as well as the factual point of view of a player in the drama.

- The interviewee’s job is to tell what happened — and what it means — from the point of view of a player, a participant, in the drama. It can be very personal and painful.

Getting Down to Details

You’re a reporter. You go out on a story. You interview one of the people involved. You go back to the newsroom and screen the footage. Along with the editor, you make notes. And decisions. What part of the interview to use? What to leave out?

You’re an anchor. Mostly, the interviewee comes to you. The interview is taped. You screen it afterwards. Along with the producer and editor, you make notes. And decisions. What part of the interview to use? What to leave out?

Automatically, in both cases, you use the most human, most emotional parts of the interview. Because that’s the part which you sense provides the real meaning. That’s the part which communicates the best. That’s — almost certainly — the most honest part.

The part of any interview most likely to bring understanding to the viewer — and, not incidentally, make the best and most powerful TV — is always the most human and most emotional part.

So leave the unemotional, institutional, unhuman stuff back on the tape. Don’t waste time. Go for the human and emotional stuff from the very beginning.

(Not incidentally, the word emotional, in the sense I use it here, doesn’t necessarily mean extremes of emotion. Like crying and laughing. It does mean having and showing strong feelings — wonder, regret, fear, sorrow, shame, bewilderment etc. In an interview, emotional simply means speaking from the heart rather than the head.)

Anima Interviewing is Hard.

Anima interviewing calls for absolute minimum of experts, spokespeople or representatives of institutions and organizations.

Nothing laid on by the ubiquitous Public Relations people,

The Anima-interviewer wants to talk to people who were there. Participants. People who can speak for themselves and express their own feelings. From the heart. From the gut. Real people.

Which brings up a problem. Sure, real people give the best interview. But real people often need help to express their feelings publicly.

Just like experts and spokespeople and representatives of institutions and organizations, most would much rather just stick to the hard facts of the situation and be done with it. It’s a lot safer.

So how does the Anima-interviewer handle that?

First, the Anima-interviewer must understand that the interviewee is, like all of us, three people in one:

- The Public Person — the person all of us hide behind. The person we want to be seen as. The person we put forward for public view. The person of the résumé.

In control. Very protective of the outward and visible persona. Representative of the tribe, its class, rules and culture, at its public best. Cool. Gives lousy interview. - The Personal Person — the “off-duty” person. The person of likes, dislikes, even some passions. Outwardly at least, open and giving. Willing to show delicate, tribally acceptable emotion if pressed.

More interesting and outgoing than the private person. But not by much. Warm. Gives ok interview. - The Private Person — the real person, behind the masks, beyond the wall. The person of fears, wants, desires, prejudices, strengths, weaknesses. Both hero and coward. Saint and sinner.

This is the raw, intimate, dangerous area of our psyches, our spirits, our souls. This is where our deepest passions, needs and hungers lie. Here is where both the heart of darkness and the splendour of light live. Here is where the Anima and Animus that is part of all of us lives. Hot. Handle with great care.

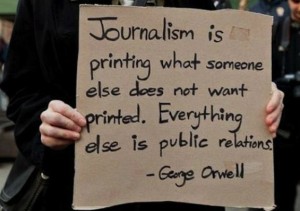

A famous Journalism quote by George Orwell.

Getting Back to the Interview

The Anima-interviewer starts the interview at the very moment of meeting the interviewee.

That’s when you start the giving.

Of yourself.

That’s the time to show real warmth, real interest, real respect.

(If you can’t, you’re not interested in other people and shouldn’t be interviewing people in the first place.)

That’s when you set the caring, respectful tone for the rest of the interview. That’s when you start the seduction.

That’s when you start the cocoon.

This stranger you’re meeting is still the Public Person. But you’re not interested in interviewing the Public Person.

So in the pre-interview you work to turn the stranger into someone you know, someone you respect. Someone who, with any luck, respects you.

By giving generously of yourself, you work to turn the Public Person into the Personal Person.

That’s when the taping starts.

Now comes the hard part — turning the Personal Person into the Private Person.

The best interviews — journeys giving the deepest insights and the harshest truths — come, of course, from the Private Person. So how do you get to the Private Person in an interview?

Gently.

Carefully.

Respectfully.

The place of the Private Person is a dangerous and delicate place to go. So decide at the beginning how far, how deep, you can legitimately probe.

How far you’re prepared to intrude.

How much you’re prepared to give as well as how much you want to get.

Know from the beginning that if you decide you’re going for the Private Person:

- It’s to find truth, not sensation.

- It’s to bring understanding, not titillation.

- It’s not to exploit, but to serve — both the interviewee and the viewer.

It’s a matter of journalistic ethics.

Only if your cause is just are you entitled to go there.

Even then, you may go there only with the permission of the interviewee.

Another Case Study

I’m working on interviewing with a CBC anchor in Calgary. I’ve asked her to bring in someone to interview.

The anchor does the interview. It’s on some fairly sensitive matter, probably sex. We play it back and I analyze it. My main criticism is that the anchor hasn’t gone far enough. Almost everything in the interview is in the area of the Public and Personal person.

The anchor hasn’t even tried to touch the Private Person.

She rationalizes that she doesn’t want to embarrass or intrude on the interviewee. She’s looking after her. Protecting her. Doesn’t want to push her into places that could be dangerous or painful for her.

The interviewee (who, by chance, is a psychiatrist) has her turn to say what happened in the interview. She says the anchor’s rationalization is pure bullshit. The anchor isn’t protecting the interviewee, she’s protecting herself. She doesn’t want to embarrass herself. She’s looking after herself.

The psychiatrist says a lot of interviewers do that. Then claim virtue for doing it.

The psychiatrist says most people really like, want and need to talk. Not just on the surface, but in depth, about matters they really care about. Even sensitive, touchy matters. Like the soul. And sex. And beliefs.

A self-censoring interviewer, she says, prevents the interviewee from giving the interview she actually wants to give — an interview that’s personal, meaningful, deep. And frequently cathartic.

So, when you interview, don’t censor yourself. Let the interviewee set any boundaries.

Not you.

View From Another Shrink

I work with another psychiatrist, Dr. Irvin Wolkoff, who has an interview program on Canadian TV.

Wolkoff talks of the “three-legged stool” school of interviewing. (All legs are vital if the stool is to stand).

Journalists who interview should find his ideas interesting.

Leg #1 — Accurate Empathy. Understand — and show you understand — the interviewee’s point of view. This doesn’t mean you take sides or make moral judgments. It does mean you find ways to accurately reflect the interviewee back to him/herself. It means you show the interviewee that the behavior under question is, at least, understandable in human terms.

Leg #2 — Unconditional Positive Regard. Show respect for the interviewee. Regardless of what she/he may or may not have done. Make clear that you understand the difference between the person and the person’s actions. That you value the other person as a fellow human being.

Leg #3 — Emotional Congruence. Never lie. Instead (always remembering that there, but for the grace of God, go you) try to find common ground. So you’re shocked by the other person’s actions? Show it. In the politest possible way, of course. But don’t judge it. You don’t have that right. Tell the truth. Don’t lie.

Being a shrink, Dr. Wolkoff feels the need to add a fourth leg to the three-legged stool.

Leg #4 — Be Innocent. Don’t be afraid to be seen as under-informed, even a bit ignorant at times. You don’t know everything. In fact, you can’t know as much about the subject in question as your interviewee. So make the interviewee teach you.

This technique (if truth can be a technique) will catch the other person off-guard, can even lead to simple, un-institutional language and human answers.

Frequently it even leads — lord help us all — to the truth.

Stop Being Strangers

Ok, so you’ve made the decision. You’re going to interview someone in depth, at the Private Person level, for all the right reasons.

You’re not exploiting. You’re not taking advantage. You’re genuinely trying to bring understanding.

The interviewee has agreed to talk. Even so, you can’t just dive into the other person’s soul, thrash around in the psyche until you get good quotes, and quit. However good your intentions.

For one thing, people won’t let you. Even when people agree to be interviewed, they’re naturally still reluctant to talk of things that matter, reveal emotions, to a stranger.

And you’re a stranger when you meet.

So you both need permission to stop being strangers.

All of us, one way or another, come from a particular tribal culture. So the interviewee needs permission from the tribe’s culture to talk to you (the stranger) from the heart, the soul.

You, (the stranger) need permission from the interviewee to even approach the heart, the soul.

How do either of you get those permissions within this relationship?

Here’s how.

- You, the stranger, take charge of the relationship and find a way to stop being a stranger. So it’s permissible for the interviewee to talk to you. From the heart. From the soul.

- It’s an Anima-thing. It’s called building a cocoon. In the field, it goes like this:

- Do thorough research and focus the interview before you meet the crew. Write the focus down. Share the focus with the crew. Readily accept suggested changes if they’re improvements.

- Make a contract with the crew that they will unobtrusively check size, coloring, and voice-level of the interviewee at first meeting. That way they won’t need to do video and audio checks just before the taped — the crucial — part of the interview.

- Include in the contract the stipulation that once introductions are over, the interviewee — body and soul — belongs to you, and you alone. Nobody else is included in the relationship. No-one may intrude. You have to build a cocoon with the interviewee. And it doesn’t include the crew.

- Meet the interviewee. This is the moment the interview starts. Introduce crew. Together, decide on interview location and form.

- Help the interviewee put on microphone if necessary. Put on your own. Put sockets in pockets, to be connected only when the taped part of interview is about to start.

- Casually ask the crew for the minimum time they’ll need to set up for the interview. Part of the contract is that you won’t bring the interviewee to the shooting location until the crew has everything ready. You want to go straight into taping the interview.

- You started the cocoon right after introducing the crew. Now you take the interviewee away to some other part of the building or outside if there’s a suitable and appropriate place. You’ve met each other but you’re still strangers. You’re an interviewer so you’re a threat. Here’s where you start to stop being strangers. Here’s where you start to stop being a threat. Here’s where you start to cocoon.

- Talk nonsense. All our tribes, to different degrees, demand that we talk nonsense at first meeting. Even with friends. For strangers, though, it’s a way for us to judge people, decide whether we like them or not, trust them or not. Before we make any other commitment.

- The apparently useless question “how are you?” for instance isn’t designed to get a real answer. The last thing you want to know is the state of the interviewee’s health! In fact, what it does is give the other person a chance to talk, unbend, unwind, work out status and, usually, tell a story. Weather and sport do nicely as nonsense-talk (particularly since we can do little about either). Religion, politics and sex, however, are not appropriate subjects at this stage. Not even if the interview is to be about religion, politics or sex.

- Explain what you want. Define parameters. Make certain the interviewee knows the purpose of the interview. Knows what role he or she is expected to play. If necessary, politely offer guidelines to behavior such as “simple, everyday language is the best” and “if you want to tell a story or two it’ll be great. But please keep stories short.”

- It doesn’t help to instruct people to talk from the heart, the Private Person. That comes — or doesn’t come — from your own cocooning.

- Be generous. This is the time to show you’re not just taking. Before you ask the interviewee to give anything to you, give the interviewer something of yourself. As much as you can. If appropriate, touch the interviewee. Use all your personality, charm, even charisma and humility if you have them.

- You’re focused on preparing the interviewee for the interview and the most important part of that preparation, for both of you, is that, somehow, you stop being strangers. So you, the interviewer, build a cocoon for the two of you.

- Probe, test, search. Find out what the interviewee thinks and feels about the subject matter. Find out how far into the Private Person you might be able to go. But this isn’t the time for interview-detail. Not yet. You don’t want to leave the interview back in this pre-interview. Move methodically towards the subject matter.

- Focus the interviewee closer and closer to the part of the interview which will be on tape. So when you get to taping it will be a natural progression, rather than an abrupt and artificial jump.

- When you’re ready and the crew’s setup time is over, escort the interviewee back to the shooting location, staying deep in two-way conversation. The crew are invisible and don’t react to your arrival. Instead, they do crew-things and neither look at nor talk to either of you. They’re ready to shoot.

- You take your seats. Microphones are plugged in, the crew make last-minute adjustments to lights and camera. There’s no talk with crew or producer or anyone else. No voice check. No loud call for silence. No countdown. No fixing hair. No wiping sweat.

- No moving chairs. You and the interviewee continue talking.

- You’ve worked out a series of visual and/or physical signals beforehand in case the camera runs out of tape, the soundperson dies and stops taping or the world ends. Continue the interview under all other circumstances.

- This is the hardest part. You have to keep discussing the subject matter but keep it away from the specific area you’ll be working in the actual interview.

- Hold the interviewee’s attention. Keep the cocoon around the two of you, Keep chatting until you get a visual or physical (not voice) signal that the camera is rolling and at speed. Don’t acknowledge the signal.

- Whichever of you is speaking finishes the sentence. Then you say casually, in the same voice you’ve been using all along, without pause, without change of manner or tone, some version of “Ok, we’re taping now.” And ask the first question in the same voice. (You need to give the warning for both ethical and legal reasons. In that order.)

- Nothing interrupts the interview. The cocoon lives.

- When it’s all over, help the interviewee come down, back to real life. It’s called afterplay and it’s just as important as foreplay.

The first in a two-part Master Class. Next week Studio Anima Interviews are tougher. But you can — you must — still try to cocoon.

This column is adapted from Tim Knight’s book Everything you’ve always wanted to know about how to be a TV Journalist in the 21st. Century but didn’t know who to ask or STORYTELLING AND THE ANIMA FACTOR, now in its second edition. It’s available on Lulu and Amazon.

Tim Knight executive produced, co-directed, wrote and narrated the 3-hour wildlife documentary trilogy Inside Noah’s Ark, shot in South Africa and broadcast on Discovery Channel, Animal Planet, PBS and 15 European networks.

CBD exceeded my expectations in every way thanks. I’ve struggled with insomnia in the interest years, and after tiring CBD like https://www.cornbreadhemp.com/products/cbd-sleep-gummies because of the first mores, I lastly practised a complete eventide of pacific sleep. It was like a arrange had been lifted off my shoulders. The calming effects were indulgent after all profound, allowing me to meaning free obviously without feeling confused the next morning. I also noticed a reduction in my daytime angst, which was an unexpected but receive bonus. The taste was a fraction rough, but nothing intolerable. Comprehensive, CBD has been a game-changer quest of my siesta and solicitude issues, and I’m thankful to procure discovered its benefits.

pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance: pharmacie en ligne – pharmacie en ligne

acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance: pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance – acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance

cost of amoxicillin prescription: amoxil – amoxicillin 800 mg price

cost of amoxicillin 875 mg

purple pharmacy mexico price list: northern doctors pharmacy – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican mail order pharmacies: northern doctors pharmacy – buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexican pharmacy northern doctors – buying from online mexican pharmacy

buying prescription drugs in mexico online [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]reputable mexican pharmacies online[/url] mexican mail order pharmacies

mexico pharmacy: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

mexico drug stores pharmacies

http://cmqpharma.com/# reputable mexican pharmacies online

purple pharmacy mexico price list

indianpharmacy com [url=https://indiapharmast.com/#]reputable indian online pharmacy[/url] indian pharmacy

https://canadapharmast.com/# rate canadian pharmacies

mail order pharmacy india: indian pharmacy paypal – pharmacy website india

online pharmacy india [url=https://indiapharmast.com/#]pharmacy website india[/url] top 10 online pharmacy in india

http://foruspharma.com/# buying from online mexican pharmacy

legal to buy prescription drugs from canada [url=http://canadapharmast.com/#]adderall canadian pharmacy[/url] canadianpharmacy com

canadian pharmacy com: canadian online pharmacy reviews – canadian pharmacy prices

https://indiapharmast.com/# world pharmacy india

https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline online india

how to get amoxicillin: buying amoxicillin in mexico – how to buy amoxycillin

https://clomiddelivery.pro/# order generic clomid no prescription

https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# order doxycycline capsules online

price for amoxicillin 875 mg: can i buy amoxicillin online – amoxicillin medicine

https://clomiddelivery.pro/# where to buy cheap clomid no prescription

https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline 150 mg price

cost generic clomid pills [url=http://clomiddelivery.pro/#]can you buy cheap clomid now[/url] can i get generic clomid without prescription

amoxicillin order online no prescription: buy amoxicillin canada – can i buy amoxicillin over the counter in australia

https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline 300 mg daily

https://ciprodelivery.pro/# buy cipro online without prescription

can you get clomid without a prescription [url=http://clomiddelivery.pro/#]can i get generic clomid prices[/url] where buy cheap clomid now

https://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid pharmacy

get cheap clomid without dr prescription: can i get clomid without prescription – can you buy generic clomid without a prescription

http://ciprodelivery.pro/# buy generic ciprofloxacin

buy cipro without rx: where can i buy cipro online – п»їcipro generic

https://amoxildelivery.pro/# amoxicillin 500mg price

paxlovid cost without insurance: paxlovid pharmacy – paxlovid buy

buy cipro without rx: ciprofloxacin mail online – buy cipro online canada