Sabata-mpho Mokae

“I have been busy writing two books. One is a novel – a love story after a manner of romances; but based on historical facts. The smash up of Barolongs at Kunana by Mzilikazi. The coming of the Boers and the war of revenge which smashed up the Matabele at Coenyane by the Allies, Barolong, Boers and Griqua when Halley’s Comet appeared in 1835 – with plenty of love, superstitions and imaginations worked in between the wars. Just like the style of Rider Haggard when he writes about the Zulus.”

He added that he was looking for a publisher. Mhudi was only published ten years later, in 1930. Now, a century later since Plaatje sat down in the cold concrete jungle of London, England, to write this novel, Mhudi is as relevant now as it was back then. Many readers in many parts of the world are still finding their thoughts and feelings in Plaatje’s text, with its language so powerful yet so beautiful.

Of major interest is how Plaatje, a black man, wrote a novel in 1920 and had his central character as a woman. He has given this character, Mhudi, after whom the novel got its name, immense power and agency, and let her shatter all myths of male supremacy. In Women’s Solidarity in Sol T. Plaatje’s Mhudi, Jenny Boźena du Preez writes: ‘One of the notable aspects of Plaatje’s treatment of these themes is that he centres women’s contribution to resistance (particularly the role of the eponymous heroine of the novel) rather than erasing them. This centrality and agency of women in the work have led to it being read, from a feminist perspective, on progressive on gender issues of its time.’

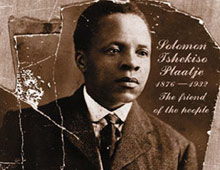

Plaatje started writing Mhudi after he had arrived in England as part of the second deputation of the South African Native National Congress in 1919. He finished writing it in 1920. The year 2020 marked a century since one of Africa’s earliest English novels by Africans was written. Due to challenges relating to publishing, Mhudi was only published in 1930.

“This book should have been published over ten years ago, but circumstances beyond the control of the writer delayed its appearance,” wrote Plaatje in the foreword.

Mhudi was the first full length English novel to be written by a black South African. Through it Plaatje carved a path on which, years later, African writers would tread on. These include Peter Abrahams who wrote Mine Boy in 1946, Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard in 1952, Mongo Beti’s The Poor Christ of Bomba in 1956 and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart in 1958.

Plaatje added that at the time when he wrote Mhudi, South African literature was “almost exclusively European”. Mhudi was what Chinua Achebe later said were “new ways to write about Africa” which he argued were also efforts of “reinvesting the continent and its people with humanity, free at last of those stock situations and stock characters, ‘never completely human,’ that had dominated European writing about Africa for hundreds of years”.

By acknowledging that South African literature was “almost exclusively European”, Plaatje took it upon himself to be the righter of that which he deemed wrong with the “almost exclusively European” South African literature, what Achebe in The Empire Fights Back said was “the colonisation of one people’s story by another”. This was the task at hand for Plaatje and other African writers of his generation and those who came after them.

What Plaatje, as well as other writers including Achebe, Tutuola, Beti, Abrahams and Thomas Mofolo did was to reimagine the African into his story, the story into which he was thrust in way he would not like to see himself, nor believe the portrayal was real, fair or affirming. These African writers re-storied Africa and the African.

One of the questions that have been keeping mainly African language and literature scholars awake at night is: Why did Plaatje, who had already made his name as modibelapuo, the one who puts up a defence for expression in mother tongue and invest time in its development, choose to write his first novel in English?

In the reasons Plaatje outlined for writing Mhudi, in the foreword, the answer to the above question has been answered: “This book has been written with two objects in view, viz. (a) to interpret to the reading public one phase of the ‘back of the Native mind’; and (b) with the readers’ money, to collect and print (for Bantu schools) Sechuana folktales which, with the spread of European ideas, are fast being forgotten. It is thus hoped to arrest this process by cultivating a love for art and literature in the vernacular.”

In Politics and Politicians of Language in African Literature, Achebe explicates the position in which Plaatje found himself with regard to the language in which he chose to write Mhudi: “No serious writer can possibly be indifferent to the fate of any language, let alone his own mother tongue. For most writers in the world, there is never any conflict – the mother tongue and the writing language are one and the same. But from time to time, and as a result of grave historical reasons, a writer may be trapped unhappily and invidiously between two imperatives.”

Zakes Mda writes On Writing Historical Fiction vs Fictionalised History that Plaatje had hoped that the envisaged commercial success of Mhudi would enable to publish books in African languages, mainly for schools. He saw African languages being under constant marginalisation due to the unrelenting spread of the use of English as a language of education, commerce and the government: This objective speaks of the author’s interest in the efficacy of the oral tradition in storing and restoring for posterity the historical memory of African societies, which he felt was fading away as a result of Westernisation.

Plaatje has also been lauded by many for his portrayal of women through the heroine of the novel, Mhudi, as visionary and way ahead of his time. DS Matjila and Karen Haire in Bringing Plaatje Home – Ga e Phetsolele Nageng: ‘Re-Storying’ the African and Batswana Sensibilities in Oeuvre, argue that Mhudi in the novel “exhibits an independence that challenges the stereotypical, traditional conception of a woman as a minor and dependent”. By so doing, they add: “Plaatje implicitly critiques African society for its exclusion of women from public decision-making and, by extension, African society’s general disregard for their potential in public life.”

Plaatje frequently shows the superior judgement of women. His elevation of women, through Mhudi in the novel, may have its genesis in his childhood and the women who lived in Pniel. Willan details this in the biography, Sol Plaatje: a life of Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje 1876 – 1942.

Plaatje’s mother was one of several women in Pniel who told him of family and tribal traditions, and from whom he learned Setswana, his first language. “The best Sechuana speakers known to me,” he observed later in life, “owe their knowledge to the teachings of a grandmother, or a mother, just as I myself … am indebted to the teachings of my mother and two aunts.”

Among these “teachings” was a fund of fables and proverbs, highly valued as repositories of the inherited wisdom of their people and passed on from generation to generation.

Another woman who left a deep impression on the young Plaatje was his paternal grandmother “Au Magritte” from whom he learnt in detail about his ancestry. It was also during his childhood that he was told about his paternal great-grandmother’s bravery.

She was gathering wood one day with some other girls in the bush near Kunana hills (so Plaatje related many years later) when they suddenly came upon a lion feasting on the carcass of a freshly killed eland. She rushed at the lion, waving her sheepskin in his face, causing him to turn tail and run off. When the girls returned home in triumph with the meat, the men would not believe their story. Only after returning to the scene where they convinced by the evidence of the spoors which revealed where the lion stood over the carcass, and how it ran away.

Mhudi can also be seen, to some extent, as a tribute to many other women who fell and rose up with Plaatje in difficult times, especially overseas while he was writing Native Life in South Africa and Mhudi.

Plaatje’s work, especially Native Life in South Africa and Mhudi, continue to draw international attention from scholars and inspire works of literature a century after it was written. The timelessness of his work is evidenced by volumes of essays in this day and age, analysing and grappling with the issues Plaatje wrote about then. His work deposits on our hands what we can use to examine life, question the centuries-old injustices and confront the assumptions that characterise life as it is at the moment long after he has ceased breathing.

- This year Jacana Media released the centenary edition of Mhudi with an introduction by Sabata-mpho Mokae. In 2020 Jacana Media also launched an edited volume titled Sol Plaatje’s Mhudi: History, Criticism, Celebration (edited by Brian Willan and Sabata-mpho Mokae).