Leonard Gentle

In South Africa, the predicted surge in Covid 19 infections and deaths is now happening. After the government caved into the business lobby to lift the lockdown despite the healthcare system not being ready, public hospitals are becoming overwhelmed and the demand for oxygen, ventilators, ICU beds and PPE is exceeding supply. The pressure from activists on the SA government to bring the private healthcare system into the public and to make more resources available is growing.

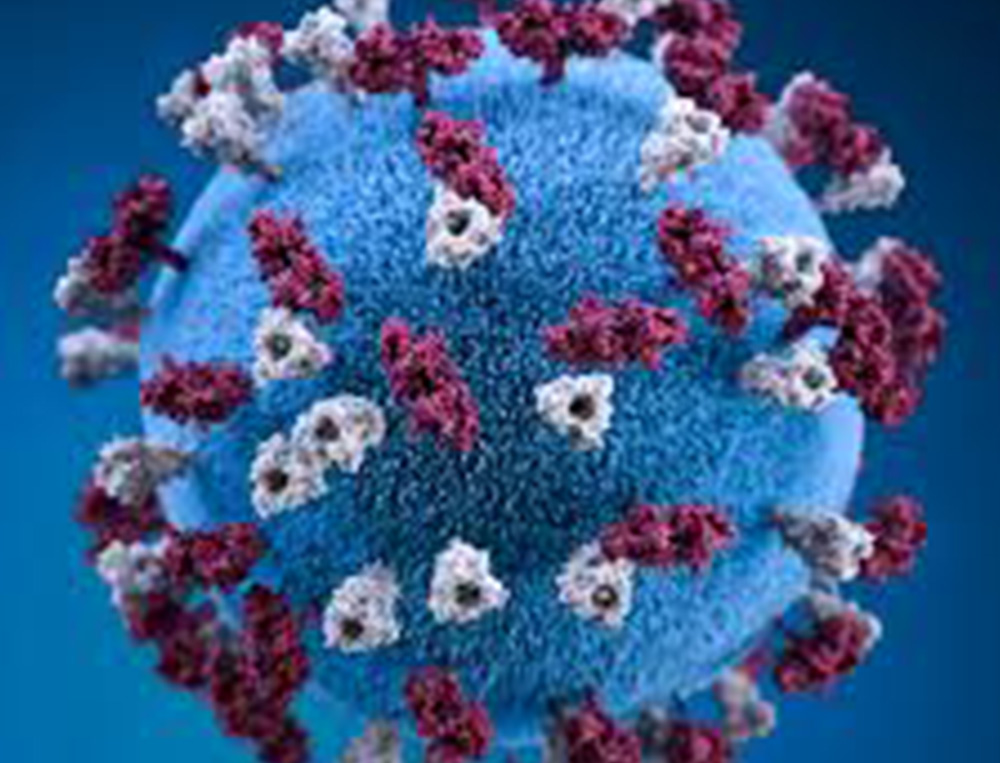

The Covid 19 pandemic has been the biggest public health crisis in the world since the Spanish flu of 1918. It has brought disease and death to many of our families and communities – and to health workers. Unless a vaccine is found and made freely available to all, Covid 19 may be with us for an extended period.

The Spanish flu came at the end of World War 1 – called “The war to end all wars” by many. But WW1 didn’t end all wars. Barely 20 years later there was World War 2. And since WW2 there has not been a single year without a major war. With Covid 19 some people, similarly, have made claims that “Covid has changed everything” and have started speculating what a “post-Covid world” may look like.

But if we are to make sense of what Covid 19 means we have to see that while it isn’t a cause of all our problems, it is, like other plagues and pathogens before – bubonic plague, small pox, Spanish Flu, Ebola, HIV – a register of the state of world. And if we are to understand what a “post Covid world” may look like we should look at what the world is like today and what the major forces shaping our world are. And what activists today can do to shape the world differently.

Meanwhile, the lessons learnt by the health scientists in dealing with Covid 19 globally are well known. From the best practices undertaken by countries like China and South Korea we know the following. Governments need to ensure public understanding and support; put in place public hygiene practices and public education; provide mass testing and tracking of all sources of the virus; institute lockdowns and social distancing, provide PPE; massively expand public healthcare (including staff, beds and ventilators) and drugs which ameliorate co-morbidities.

And, because lockdowns will destabilise livelihoods, governments must budget for programmes of wage and income compensation and food security.

All of these require massive state investment in public services and regulation of private investment so that the public good may be served. And they require global cooperation in the health sciences, on social distancing and tracking and in the search for ameliorative drugs and a vaccine.

The problem is that the governments of almost all countries in the world have been moving in the opposite direction for the last 30 years – instead of state investment in public services and jobs they have been cutting state budgets, deregulating private capital and privatising services; and instead of international co-operation there has been more global conflict.

This has meant that when the pandemic spread governments have been tardy, health services have been poorly-prepared and the quest for a vaccine is undermined by years of neglect in what the pharmaceutical industry did not deem a profitable investment and is now caught up in patent rights and national rivalry. And ordinary people simply do not trust governments and have had to be forced to comply with social distancing.

To see our way to understanding why most governments have been doing the opposite, and being so poorly prepared for Covid, we should realise that there have been three major trends going on over the last 30 years …

1. Firstly, there is, since the early 1970s, an ongoing crisis of capitalism stuck in a long wave of stagnation – in terms of outputs, growth, employment and profit rates. The series of political and economic measures taken by almost all governments to address this problem – deregulating finance markets, the securitisation of debt, the commercialisation and privatisation of what were once public services, cross-border systems of production and the financialisation of economic life – unleashed the era of neo-liberalism.

But, far from neo-liberalism solving the crisis, it led to its own chapter – the 2008 “financial crisis”.

In response the major states all cut interest rates to near zero, pumped more than $10 trillion into private banks through Quantitative Easing, bailed out the corporations deemed to be “too big to fail” and even partially nationalised some companies.

While the epi-centre of this crisis was the private sector in the USA, the re-packaging of money into arcane financial vehicles and the globalised system of financialisation saw European governments bear the brunt of the costs of these bail outs as a “public debt” crisis.

Their populations experienced this as a new obsession by European countries with austerity. The most ruthless cuts in public services – including health services – since the first emergence of the welfare state after WW2.

It was no accident that once global travel brought COVID 19 to European countries such as Italy, Spain, and France, they were simply incapable of coping.

2. The second global upheaval is the geo-political war between the USA and its old Cold War adversaries – China and Russia. Today, this is not a war based on ideology, but is simply a product of US aggression against any competing power.

At the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 US corporations and other Western TNCs stood ready to conquer the old Eastern Bloc and find new sources for accumulation, whilst the US extended NATO up to the crumbling remains of Russia. In response Putin’s Russia launched a nationalist project however, uniting and disciplining its recently privatised energy sector to establish itself as rival power to the USA.

China is clearly intent on challenging US and the current uni-polarity of the world order. It has two strings in its bow – the Renminbi is challenging the US dollar as the world’s trade currency and, more importantly, as the world’s reserve currency and, via its Belt-and Road project, it is hoovering up allies all over the developing world.

And with the Covid 19 pandemic it has become the world’s exemplar. But with the West fighting China they were not going to copy its best practice.

Meanwhile, together with regional allies, the US steps up its vindictive economic and political wars against Iran and Venezuela- countries hard-hit by Covid 19. Instead of co-operation Trump’s USA is hell-bent on destroying the WHO.

3. The Third global upheaval, which has been exposed by the pandemic, is a political crisis. Whilst China and Russia have authoritarian regimes whose power is currently unassailable, none of the countries in the West has a government with any political authority to do anything decisive. And many of the countries in the global south share some of the same features of lack of legitimacy.

A common denominator in the USA and Europe is that the sources of this lack of legitimacy lie in the consequences of the actions pursued by the governing elite in responding to the 2008 Financial Crisis. Briefly, the strategy of bailing out the rich and foisting austerity on the poor, has caused so much public anger that the cosy Centre-Right-Centre-Left two-Party “gentlemanly” sharing of electoral cycles has been shattered. In France, in Germany, in Spain, in Ireland, in Italy. None of the post WW2 political party arrangements have survived. Those that have – like in the USA – have seen the hollowing out of the centre of these parties.

It is this political crisis which is a factor as much as the pandemic that is making governments act as they do…

The first of the European countries to implement a lock-down was Italy.

But Italy hasn’t had a functioning government since the EU decided to appoint their own functionary as Prime Minister after Italy had become the epi-centre of Europe’s debt crisis in 2008/2009.

Italy is ruled by a coalition with little public credibility. Infection rates rose and death rates because of this lack of credibility made lock-downs initially impossible to implement.

Spain was the heartbeat of the 2010/2011 phase of public occupations of central squares in the aftermath of the Arab Spring. The Indignados of Madrid were the inspiration for the formation of a new political movement, Podemos, which has challenged Spain’s post-Franco duopoly of the Socialist, PSOE (on the centre-Left) and the Partido Popular (on the Right).

Spain has had three inconclusive elections over 2018 and 2019, none of which has delivered a majority for any party to form a workable government.

Then there is the ongoing issue of the Catalan independence movement, which threatens to dismember Spain’s richest area. The leaders of an initiative to hold a Catalan independence referendum in 2018 have just been jailed for treason.

Spain’s Covid 19 crisis and its response is at least partly to do with this political vacuum.

France’s Macron won the 2018 Presidential elections in the second round after getting less than 25% of the popular vote in the first round. He claims to be an outsider of France’s main political parties and is a hugely unpopular figure in that country.

He has been confronted with the largest ongoing social movement – the Gilets Jaunes (Yellow Vests) – which brought much of France to a standstill as they occupied public spaces for over a year. Then his attempts at pushing through pension “reforms” saw France’s labour movement mount waves of strikes and were at a deadlock when the Covid 19 hit France.

Then there is Boris Johnstone’s Britain. Johnstone won the 2019 elections with the promise to “get Brexit done”. But Brexit was an outcome of a referendum in 2015 in which the voters thumbed their noses at the whole political class, the economists and the commentariat who warned that Brexit would be a disaster for all.

Johnstone’s promises have split his own party and he is left with having to appease an electorate who wanted Brexit but who hate the austerity imposed on them since the 2008 crisis.

And then there is Trump. The world’s richest country is also the one with the worst and most expensive healthcare system of any of the “developed” nations.

The 2016 elections saw the surprise election of a real estate ignoramus over the ultimate Washington insider, Hilary Clinton.

Since then Trump has faced internal rebellions within the US state and even the threat of impeachment. And now there is the Black Lives Matter movement. And 2020 is an election year.

The USA exemplifies the political crisis of our times. The disjunct between the power of the USA and the quality of its political leadership has never been more glaring.

Which brings us to Africa …

State authority has been destroyed in Libya and Somalia. Sudan and Algeria have had insurrections through 1918 and 1919 and there is still no effective authority. The Nigeria government only has full authority over its Southern states.

Covid 19 was a difficult moment for the South African government. Alongside so many countries in the West they dithered while the news came out of China and the WTO that a new corona virus was on the way. Our 2020 budget still had as its centre-piece cuts in the health budget, despite the fact that the virus was on its way.

But to its credit government did respond in March with the lock downs and social distancing. The logic of the lock downs was that they were necessary to flatten the growth of Covid infections so that the healthcare system could be prepared.

Prior to the Covid 19 pandemic there had been a consensus amongst both the health science community and government that South Africa’s healthcare system was not fit for purpose. It was a dual system whereby 80% of the people rely on the public sector while the 20%, the wealthy and the middle classes – who have one or other medical aid – relied on the private sector.

Over the last 5 years Government had unveiled its commitment to universal healthcare via the National Health Insurance (NHI) policy. But when Covid 19 struck government’s commitment to the healthcare reforms to make universal healthcare possible, simply dissipated.

And when the clamour came from business and other lobbying groups for an immediate opening up of “the economy” it was left to defensive voices amongst the poor – community organisations and trade unions – to raise the battle for testing and PPE.

In a situation where government is practising the diseased politics of doing whatever to appease the markets rather than to dealing with the threats posed to the poor majority, the key will be not to merely stay at home under lock down and leave all the big decisions to government. The key will be how do we continue to find means of social mobilisation even under the shadow of the pandemic.