Thapelo Mokoatsi

The man is a voluminous writer. He is dramatist, essayist, critic, novelist, historian humorist, biographer, translator and poet at the same time. I put “Poet” last in the list not that poetry is the least of his accomplishments but for emphasis’ sake as that is what the man really is. Every day of his life the public is thrilled by his sublime productions through the press, through his books and other publications.

At a time when Africa’s rich oral tradition was battling to keep pace with modernity, a remarkable 20th Century poet rescued a swathe of our cultural legacy from obscurity.

As a schoolboy, the late Nelson Mandela had the honor of meeting the striking S E K Mqhayi. Madiba recounts the experience:

“The sight of a black man in tribal dress coming through that door was electrifying. It is hard to explain the impact it had on us. It seemed to turn the universe upside down. He raised his assegai into the air for emphasis, and accidentally hit the curtain above him. He faced us, and newly energised, exclaimed that this incident – the assegai striking the wire – symbolized the clash between the culture of Africa and that of Europe.

His voice rose and he said: ‘…the assegai stands for what is glorious and true in African history; it is a symbol of the African as warrior and the African as artist.”

The Young Mandela by David James Smith, Weidenfeld & Nicolson

True to the curtain encounter, Mqhayi wielded his artistry as a formidable weapon. He was a pioneer of indigenous languages. As a linguist and key thinker of the early 1900s, he embarked on the arduous project of standardising the grammar of isiXhosa. As a storyteller and provocative journalist, he established himself as a raconteur of our fears, our histories and our aspirations.

Mqhayi’s poetry and prose was his hallmark as a most unusual Imbongi, praise singer, poet and keeper of history. He explored the complex nature of history, morality, justice, truth and, of course, love. But his artistry delved much deeper.

Customarily, the role of Imbongi focused mainly on the local tribe and community, praising or criticising the power structures to promote the welfare and morality of everyone. But he did not limit himself to these traditional issues or to only chronicling history. He also expressed his opposition to the settlers, colonialism and its attendant injustices.

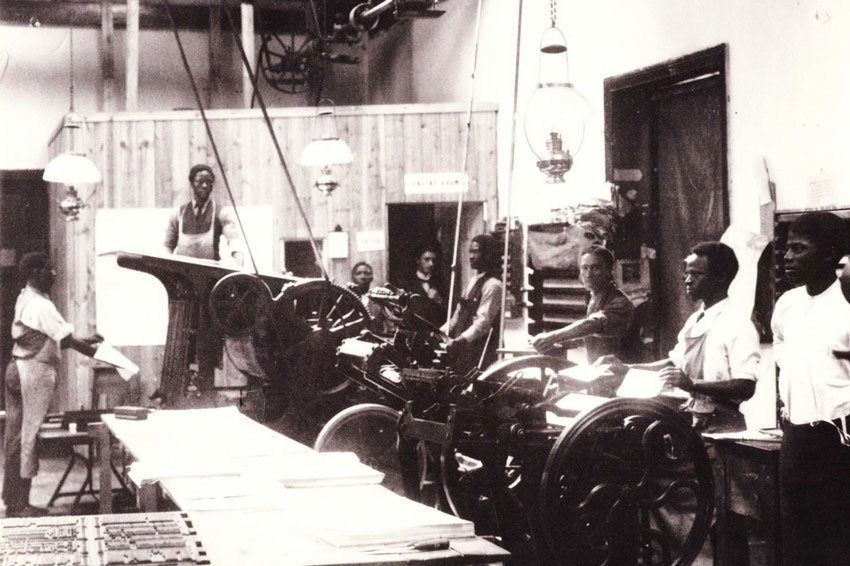

For Mqhayi to do this effectively, the use of the emergent print industry was essential. So in 1897 Mqhayi, Allan Kirkland, Tiyo Soga and others launched their own newspaper, Izwi Labantu (Voice of the People). The paper was a direct competitor of John Tengo Jabavu’s Imvo Zabantsundu.

Mainstreaming African Languages

Mqhayi and his contemporaries accused Jabavu’s publication of adopting a “reactionary political line”. In addition, Mqhayi argued for the primacy of isiXhosa. Jabavu believed that English was central for his newspaper to assert a notion of modernity.

This was the beginning of Mqhayi’s commitment to promoting African languages, not only for literary expression, but also as an integral element of an emergent political consciousness that opposed colonial values.

For Mqhayi, the survival of African languages in modernity was important to dislodge the hegemony of English. Izwi Labantu was filled with provocative writing on language and culture. The paper, and Mqhayi’s work in general, helped to ensure that isiXhosa survived and thrived, beyond it’s mother tongue status. Izwi Labantu was an act of political and cultural resistance.

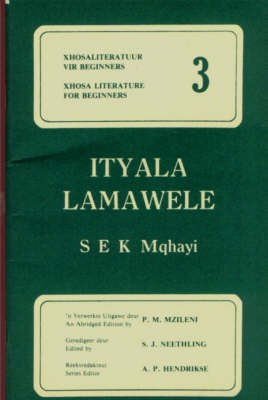

Ityala Lamawela (The Lawsuit of the Twins) often described as a defense of traditional pre-conditional law, was Mqhayi’s first novel.

In one of his seminal works of prose in Izwi, Mqhayi observed:

“Ukuhamba behlolela iinkosi zabo ezibahlawulayo umhlaba. Bahamba nalo ilizwi ukuba lihamba liba yingcambane yokulawula izikhumbani nesizwe, yathi imfuno yayinto nje eyenzelwe ukuba kuviwane ngentetho.”

Translation:

Human movement in search of land grabbing land from chiefs. Using the word of God as a tool and instrument to rule kings and nations. An education so inferior became an institution to prepare slaves for new masters.

Translation by Mncedisi Qanqubi (2012)

Before Mqhayi’s birth, his father Ziwani Krune Mqhayi and mother Qashani Bedle prayed diligently for a baby boy. Their prayers were answered and they named him “Samuel”. It is Hebrew for “asked of God”. The name expressed their gratitude for answered prayers.

Both Ziwani and Qashani Mqhayi had a common wish for their son, Samuel. They hoped that he would “train for holy orders” and become a priest. Little did they know that Mqhayi’s life would take a very different turn.

The Eastern Cape region was home to intellectual greats like Tiyo Soga, Tengo Jabavu, Mpilo Walter and Benson Rubusana. Mqhayi learned from them and carved a niche for himself as poet and intellectual. Together they were the pioneers of a milieu that had a profound impact on our cultural life. They were a counter force for the aggressive attempts of the settlers and foreign missionaries to obliterate African traditions.

Oral tradition & modernity

Mqhayi developed his passion for poetry and storytelling through the fireside tradition of amabali –- tales of long ago. As a young boy growing up in the village of Gcumashe, on the banks of the Thyume River, Mqhayi listened intently as the elders shared stories about the struggles and triumphs of Xhosa greats like Hintsa kaKhawuta and Gcaleka kaPhalo.

It was the rich indigenous history of amaXhosa that inspired Mqhayi to discover and hone his passion for the oral tradition as a medium of storytelling. His influence on storytelling and the oral tradition continues to inspire us today. In 2010, Mqhayi was given the Chairpersons’ award posthumously by the South African Literary Awards for his life work. Mqhayi, known as Imbongi Yesizwe Jikelele (The Poet of the Nation All Over), was being honoured for his ability to chronicle stories of South Africa’s diverse people and even beyond our borders. In his work, Mqhayi persistently called for African people to be united.

Mqhayi is recorded as the first Imbongi with a published literary collection. A monument stands in his honour just outside Berlin, East London. It reminds us the Mqhayi was no ordinary Pioneer.

He kept piercing the curtains so that we never ever lost sight of our past and it’s rich traditions.

Picture this – 3 am in the morning, I had a line of fiends stretched around the corner of my block. It was in the freezing middle of January but they had camped out all night, jumping-ready to buy like there was a sale on Jordans. If you were 16 years old, in my shoes, you’d do anything to survive, right? I got good news though; I MADE IT OUT OF THE HOOD, with nothing but a laptop and an internet connection. I’m not special or lucky in any way. If I, as a convicted felon that used to scream “Free Harlem” around my block until my throat was sore, could find a way to generate a stable, consistent, reliable income online, ANYONE can! If you’re interested in legitimate, stress-free side hustles that can bring in $3,500/week, I set up a site you can use: https://incomecommunity.com

Great post. I was checking continuously this blog and I’m impressed! Very helpful information specially the last part 🙂 I care for such info a lot. I was looking for this certain information for a long time. Thank you and good luck.

I respect your piece of work, appreciate it for all the useful posts.

It¦s actually a nice and useful piece of information. I am satisfied that you simply shared this useful information with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

I simply wanted to say thanks yet again. I am not sure the things that I would’ve made to happen in the absence of the type of basics revealed by you directly on that concern. Completely was an absolute horrifying setting in my circumstances, nevertheless taking note of the very well-written style you dealt with it made me to weep with contentment. I am just grateful for the support and even wish you are aware of an amazing job you were providing educating many people using your web blog. I am sure you’ve never met all of us.

But wanna say that this is invaluable, Thanks for taking your time to write this.

I really like your writing style, excellent info, regards for posting :D. “Nothing sets a person so much out of the devil’s reach as humility.” by Johathan Edwards.

I am extremely impressed with your writing skills and also with the layout on your weblog. Is this a paid theme or did you modify it yourself? Either way keep up the nice quality writing, it is rare to see a nice blog like this one these days..

Oh my goodness! a tremendous article dude. Thanks However I am experiencing subject with ur rss . Don’t know why Unable to subscribe to it. Is there anybody getting identical rss downside? Anybody who is aware of kindly respond. Thnkx

Do you mind if I quote a couple of your posts as long as I provide credit and sources back to your website? My blog is in the exact same niche as yours and my visitors would genuinely benefit from a lot of the information you provide here. Please let me know if this okay with you. Regards!

Excellent post. I was checking constantly this blog and I’m impressed! Extremely useful information specially the last part 🙂 I care for such information much. I was looking for this certain info for a long time. Thank you and good luck.

I always was interested in this subject and stock still am, appreciate it for putting up.

Get-X – онлайн игра с реальным выводом средств. В неё входят азартные игры, где можно делать ставки, например, Краш.

Nice post. I learn one thing tougher on different blogs everyday. It would at all times be stimulating to learn content from different writers and apply slightly one thing from their store. I’d desire to use some with the content on my blog whether you don’t mind. Natually I’ll offer you a link on your web blog. Thanks for sharing.

You have brought up a very wonderful points, thanks for the post.

Hi there, I discovered your blog by means of Google even as searching for a similar matter, your web site got here up, it appears to be like good. I have bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

Hey very cool site!! Man .. Excellent .. Amazing .. I will bookmark your blog and take the feeds also…I’m happy to find so many useful information here in the post, we need work out more strategies in this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

Great website. Plenty of helpful info here. I am sending it to a few pals ans also sharing in delicious. And certainly, thank you on your effort!

good post.Never knew this, regards for letting me know.

You have remarked very interesting details ! ps decent site.

Magnificent site. Lots of useful information here. I’m sending it to a few friends ans also sharing in delicious. And obviously, thank you to your sweat!

You can certainly see your skills in the paintings you write. The sector hopes for even more passionate writers such as you who are not afraid to mention how they believe. Always go after your heart. “He never is alone that is accompanied with noble thoughts.” by Fletcher.

whoah this weblog is magnificent i like studying your articles. Stay up the great paintings! You already know, many people are looking around for this info, you could help them greatly.

You have mentioned very interesting details! ps nice internet site.

Do you mind if I quote a few of your articles as long as I provide credit and sources back to your webpage? My blog site is in the very same niche as yours and my users would certainly benefit from some of the information you present here. Please let me know if this ok with you. Thanks!

After study a few of the blog posts on your website now, and I truly like your way of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website list and will be checking back soon. Pls check out my web site as well and let me know what you think.

I like this post, enjoyed this one regards for posting.

You are my aspiration, I have few web logs and sometimes run out from to brand.

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across. It extremely helps make reading your blog significantly easier.

Simply want to say your article is as amazing. The clarity in your post is just cool and i can assume you are an expert on this subject. Well with your permission let me to grab your feed to keep updated with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please carry on the gratifying work.

But wanna remark that you have a very nice web site, I like the design and style it really stands out.

I simply wanted to thank you so much again. I am not sure the things that I could possibly have gone through in the absence of these tips revealed by you concerning this industry. It had become an absolute horrifying concern for me, nevertheless witnessing the specialised way you treated it took me to cry for fulfillment. I am just grateful for the information and thus wish you realize what a great job you were undertaking training other individuals with the aid of your blog post. Most likely you’ve never met any of us.

Appreciate it for all your efforts that you have put in this. very interesting information.

Good post and straight to the point. I am not sure if this is really the best place to ask but do you folks have any thoughts on where to employ some professional writers? Thanks in advance 🙂

Nice read, I just passed this onto a colleague who was doing a little research on that. And he just bought me lunch because I found it for him smile Thus let me rephrase that: Thanks for lunch!

I have read a few good stuff here. Definitely worth bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how much effort you put to create such a wonderful informative web site.

I’m usually to running a blog and i really admire your content. The article has really peaks my interest. I am going to bookmark your website and preserve checking for brand new information.

You can definitely see your enthusiasm in the work you write. The sector hopes for more passionate writers such as you who are not afraid to say how they believe. At all times go after your heart.

Thanks for your entire work on this blog. Ellie really loves doing research and it is easy to understand why. Most of us learn all regarding the powerful tactic you give worthwhile things by means of your website and in addition increase response from others on that topic while our favorite princess is without a doubt discovering a lot of things. Take advantage of the remaining portion of the year. You are doing a terrific job.

Thank you for some other informative site. Where else may just I get that kind of info written in such an ideal method? I have a undertaking that I am just now operating on, and I’ve been at the look out for such info.

Loving the info on this site, you have done great job on the content.

Magnificent goods from you, man. I have understand your stuff previous to and you are just extremely fantastic. I really like what you’ve acquired here, certainly like what you’re stating and the way in which you say it. You make it entertaining and you still take care of to keep it smart. I can not wait to read far more from you. This is actually a great web site.

Your article was a superb read. I enjoyed the way you organized the information and the illustrations you used were incredibly informative. Your prose is clear, and I learned the article to be straightforward. Thank you for sharing such an educational article.

I got what you intend,saved to favorites, very nice web site.

I’m not sure where you are getting your info, but great topic. I must spend some time learning much more or figuring out more. Thanks for wonderful info I used to be looking for this information for my mission.

Write more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seems as though you relied on the video to make your point. You clearly know what youre talking about, why waste your intelligence on just posting videos to your blog when you could be giving us something enlightening to read?

Im now not certain the place you are getting your info, but great topic. I needs to spend some time finding out much more or figuring out more. Thanks for great info I used to be looking for this information for my mission.

What’s Going down i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve found It absolutely helpful and it has helped me out loads. I hope to give a contribution & assist different customers like its aided me. Great job.

It¦s really a great and useful piece of information. I¦m satisfied that you simply shared this helpful information with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

I would like to thank you for the efforts you have put in writing this site. I’m hoping the same high-grade web site post from you in the upcoming also. In fact your creative writing skills has inspired me to get my own website now. Really the blogging is spreading its wings rapidly. Your write up is a great example of it.

Greetings I am so thrilled I found your blog page, I really found you by accident, while I was searching on Digg for something else, Anyhow I am here now and would just like to say kudos for a incredible post and a all round interesting blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to read through it all at the minute but I have book-marked it and also added in your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read much more, Please do keep up the awesome work.

Hey, you used to write wonderful, but the last several posts have been kinda boring… I miss your great writings. Past several posts are just a little out of track! come on!

You made some first rate factors there. I appeared on the web for the difficulty and located most people will associate with together with your website.

I have recently started a web site, the information you offer on this website has helped me greatly. Thank you for all of your time & work.

You really make it seem so easy with your presentation but I find this matter to be actually something which I think I would never understand. It seems too complicated and extremely broad for me. I am looking forward for your next post, I will try to get the hang of it!

I was curious if you ever thought of changing the layout of your website? Its very well written; I love what youve got to say. But maybe you could a little more in the way of content so people could connect with it better. Youve got an awful lot of text for only having 1 or 2 images. Maybe you could space it out better?

Really fantastic info can be found on blog. “Politics is applesauce.” by Will Rogers.

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across. It extremely helps make reading your blog significantly easier.

Hi there! I could have sworn I’ve been to this website before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyhow, I’m definitely delighted I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back frequently!

I regard something really interesting about your weblog so I bookmarked.

I gotta bookmark this site it seems very beneficial handy

great post, very informative. I wonder why the other specialists of this sector don’t notice this. You must continue your writing. I’m confident, you have a huge readers’ base already!

Just wanna tell that this is invaluable, Thanks for taking your time to write this.

Thanks a lot for providing individuals with an extremely memorable chance to check tips from this site. It’s always so good plus jam-packed with a great time for me personally and my office co-workers to visit your site nearly 3 times in one week to read through the newest items you have got. And indeed, I’m just at all times amazed for the good techniques served by you. Certain 1 facts in this post are easily the simplest we’ve ever had.

whoah this weblog is excellent i like reading your articles. Keep up the great work! You recognize, lots of individuals are looking around for this information, you could help them greatly.

I think you have noted some very interesting points, appreciate it for the post.

Would you be inquisitive about exchanging hyperlinks?

Some truly nice and useful info on this web site, as well I think the style and design has excellent features.

I have been checking out some of your articles and i must say pretty clever stuff. I will definitely bookmark your website.

Hey, I think your site might be having browser compatibility issues. When I look at your website in Firefox, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, amazing blog!

Keep up the fantastic piece of work, I read few posts on this internet site and I conceive that your web blog is very interesting and holds circles of excellent information.

I went over this web site and I conceive you have a lot of superb info, bookmarked (:.

Definitely imagine that that you stated. Your favourite justification appeared to be at the internet the simplest factor to bear in mind of. I say to you, I certainly get irked whilst other people think about worries that they just don’t understand about. You controlled to hit the nail upon the top and also defined out the entire thing without having side-effects , other people could take a signal. Will likely be again to get more. Thanks

I really like your writing style, good information, thank you for putting up :D. “You can complain because roses have thorns, or you can rejoice because thorns have roses.” by Ziggy.

You are my breathing in, I have few web logs and sometimes run out from post :). “Fiat justitia et pereat mundus.Let justice be done, though the world perish.” by Ferdinand I.

I just could not depart your website before suggesting that I actually enjoyed the standard information a person provide for your visitors? Is going to be back often in order to check up on new posts

I have been exploring for a little for any high-quality articles or blog posts on this sort of area . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this web site. Reading this info So i am happy to convey that I have a very good uncanny feeling I discovered exactly what I needed. I most certainly will make certain to do not forget this web site and give it a look on a constant basis.

What’s Taking place i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I have found It absolutely helpful and it has aided me out loads. I am hoping to contribute & aid different customers like its aided me. Good job.

Some genuinely interesting info , well written and generally user genial.

Hi there! This post couldn’t be written any better! Reading through this post reminds me of my previous room mate! He always kept talking about this. I will forward this article to him. Pretty sure he will have a good read. Thank you for sharing!

That is the correct blog for anybody who desires to find out about this topic. You realize a lot its almost hard to argue with you (not that I really would need…HaHa). You positively put a brand new spin on a topic thats been written about for years. Nice stuff, simply great!

I simply wanted to compose a message in order to appreciate you for those precious hints you are giving at this site. My time intensive internet look up has finally been compensated with beneficial ideas to write about with my friends. I would believe that most of us visitors are truly lucky to dwell in a decent community with so many awesome individuals with interesting principles. I feel pretty fortunate to have discovered the website and look forward to plenty of more pleasurable times reading here. Thanks once again for a lot of things.

Some genuinely superb blog posts on this website, appreciate it for contribution. “An alcoholic is someone you don’t like who drinks as much as you do.” by Dylan Thomas.

Its like you learn my mind! You seem to know so much about this, like you wrote the e-book in it or something. I feel that you simply could do with some percent to force the message home a little bit, however other than that, this is wonderful blog. A fantastic read. I’ll certainly be back.

magnificent post, very informative. I wonder why the other specialists of this sector don’t notice this. You must continue your writing. I’m confident, you have a huge readers’ base already!

Good post. I study one thing tougher on different blogs everyday. It is going to always be stimulating to read content material from other writers and follow a little bit something from their store. I’d choose to use some with the content material on my blog whether you don’t mind. Natually I’ll offer you a hyperlink in your web blog. Thanks for sharing.

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read anything like this before. So nice to seek out anyone with some authentic thoughts on this subject. realy thank you for starting this up. this web site is something that is wanted on the net, somebody with slightly originality. helpful job for bringing something new to the internet!

Deference to author, some good information .

I?¦ve recently started a site, the information you provide on this site has helped me greatly. Thanks for all of your time & work.

Hello my loved one! I wish to say that this post is awesome, great written and come with approximately all significant infos. I’d like to peer extra posts like this.

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information. Your website is very useful. Thanks for sharing.

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain nice points in features also.

Your style is so unique compared to many other people. Thank you for publishing when you have the opportunity,Guess I will just make this bookmarked.2

I like what you guys are up also. Such clever work and reporting! Carry on the superb works guys I have incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it’ll improve the value of my website 🙂

But wanna comment that you have a very decent internet site, I love the design and style it actually stands out.

What i don’t realize is if truth be told how you’re not really a lot more neatly-preferred than you might be now. You’re very intelligent. You recognize thus significantly in relation to this matter, produced me in my opinion believe it from numerous numerous angles. Its like women and men aren’t interested except it is one thing to do with Girl gaga! Your individual stuffs great. At all times handle it up!

Its superb as your other content : D, regards for posting. “If Christ were here now there is one thing he would not be–a christian.” by Mark Twain.

Hey there, You’ve done a fantastic job. I will certainly digg it and personally recommend to my friends. I am confident they’ll be benefited from this web site.

Hmm is anyone else experiencing problems with the pictures on this blog loading? I’m trying to find out if its a problem on my end or if it’s the blog. Any suggestions would be greatly appreciated.

I am constantly invstigating online for ideas that can facilitate me. Thanks!

Thank you a lot for giving everyone remarkably special chance to discover important secrets from this blog. It is usually very excellent plus stuffed with amusement for me personally and my office fellow workers to search the blog really thrice every week to read the latest secrets you have. Of course, we’re certainly impressed for the staggering techniques you give. Some 4 facts in this post are certainly the finest we have all had.

Very great post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wished to mention that I have truly enjoyed surfing around your weblog posts. After all I will be subscribing in your rss feed and I hope you write once more very soon!

Nice blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere? A theme like yours with a few simple tweeks would really make my blog jump out. Please let me know where you got your design. Thanks

so much excellent info on here, : D.

You actually make it seem so easy with your presentation but I find this matter to be actually something which I think I would never understand. It seems too complicated and very broad for me. I’m looking forward for your next post, I will try to get the hang of it!

Wonderful website. Lots of useful info here. I am sending it to some pals ans additionally sharing in delicious. And obviously, thanks in your sweat!

WONDERFUL Post.thanks for share..extra wait .. …

Pretty great post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and wanted to mention that I’ve truly enjoyed surfing around your weblog posts. In any case I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I’m hoping you write again very soon!

fantastic post.Ne’er knew this, thanks for letting me know.

An interesting discussion is worth comment. I think that you should write more on this topic, it might not be a taboo subject but generally people are not enough to speak on such topics. To the next. Cheers

Your place is valueble for me. Thanks!…

Some really interesting info , well written and loosely user pleasant.

Hi! I just wanted to ask if you ever have any issues with hackers? My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing months of hard work due to no data backup. Do you have any methods to prevent hackers?

Good day! I know this is kinda off topic however , I’d figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in exchanging links or maybe guest authoring a blog article or vice-versa? My site discusses a lot of the same subjects as yours and I feel we could greatly benefit from each other. If you happen to be interested feel free to shoot me an e-mail. I look forward to hearing from you! Excellent blog by the way!

Best Porn Site Ever: Vagina

Best Porn Site Ever: Porno

Best Porn Site Ever: Wetback

Best Porn Site Ever: Gay Sex

Best Porn Site Ever: Pre Teen

Best Porn Site Ever: Goodpoop

Best Porn Site Ever: Kike

Best Porn Site Ever: Wartenberg Wheel

Best Porn Site Ever: One Cup Two Girls

Best Porn Site Ever: Carol Queen

Best Porn Site Ever: Zoccole

Best Porn Site Ever: Paris Hilton

Best Porn Site Ever: Ass

Best Porn Site Ever: Rusty Trombone

Best Porn Site Ever: Clit

Best Porn Site Ever: Cunnilingus

Best Porn Site Ever: Dolcett

Best Porn Site Ever: Coprophilia

Best Porn Site Ever: Butt

Best Porn Site Ever: Sexo

Best Porn Site Ever: Hot Chick

Best Porn Site Ever: Jiggerboo

Just wanna input on few general things, The website style and design is perfect, the written content is real superb : D.

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Freeones

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: R@Ygold

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ejaculation

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tubgirl

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ball Sucking

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shanna Katz

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dick

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Vivid

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dirty Sanchez

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bisexual

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Amateur

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ducky Doolittle

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sadie Lune

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Doggiestyle

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Betty Dodson

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Poopchute

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sleazy D

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Threesome

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Slanteye

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Squirt

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jizz

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Kike

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Scissoring

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Chocolate Rosebuds

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Goregasm

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Clitoris

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sucks

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sex

you might have an excellent blog right here! would you wish to make some invite posts on my blog?

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nigga

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Girls Gone Wild

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shauna Grant

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dommes

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Immagini di Cazzo

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nimphomania

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Swastika

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sultry Women

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Zoophilia

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gay Dog

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Lesbian

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Menage A Trois

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bastinado

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Booty Call

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sexy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gringo

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Busty

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dirty Pillows

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shrimping

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Stormfront

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: 2G1C

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Zoccole

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Yiffy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Camel Toe

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ball Gravy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ducky Doolittle

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Lsd

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nimphomania

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Doggystyle

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Asshole

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Wartenberg Pinwheel

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bitch

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Eunuch

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sasha Grey

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Semen

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Voyeur

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: One Cup Two Girls

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Juggs

I was examining some of your content on this site and I believe this website is rattling instructive! Keep on posting.

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bollocks

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Double Dong

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Grope

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Upskirt

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Kinkster

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Figging

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Handjob

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Poopchute

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Boob

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Preteen

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Linda Lovelace

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Kinkster

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Kinkster

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Buttcheeks

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cock

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Yellow Showers

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Clit

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fudge Packer

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fisting

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cunt

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Carpetmuncher

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: A2M

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Huge Fat

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fessa

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pthc

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Slanteye

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Mdma

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tranny

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dog Style

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Meats

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Mr Hands

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Boner

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rape

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Madison Young

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: How To Murder

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rosy Palm

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bitch

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: How To Kill

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Acrotomophilia

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Panty

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Golden Shower

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Masturbate

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Twinkie

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hot Chick

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hand Job

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Miki Sawaguchi

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Murder

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Foot Fetish

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Big Black

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Wank

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jordan Capri

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Chastity Belt

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Leather Restraint

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Babeland

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sesso a pagamento

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Omorashi

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Swinger

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Scat

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tranny

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tit

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shanna Katz

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Puttane

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hot Chick

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Poop Chute

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Voyeur

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shaved Beaver

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: New Pornographers

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Porno

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bulldyke

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Motherfucker

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jackie Strano

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dommes

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Meats

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Panty

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Voyeur

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jiggerboo

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pubes

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Naughty

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Carol Queen

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ball Gravy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pleasure Chest

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cocks

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Big Tits

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Philip Kindred Dick

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Genitals

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rectum

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Serviture

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Golden Shower

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fessa

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Vivid

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Panty

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Are Idiots

As soon as I noticed this site I went on reddit to share some of the love with them.

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Queaf

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bangbros

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Knobbing

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Erotism

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Swinger

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cleveland Steamer

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Get My Sister

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dommes

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Suck

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nymphomania

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hookup

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bisexual

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Deep Throat

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shota

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rosy Palm And Her 5 Sisters

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Leather Restraint

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Lovemaking

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Homoerotic

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shar Rednaur

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Latina

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: One Cup Two Girls

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Vorarephilia

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Girl On

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Prince Albert Piercing

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Amateur

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Humping

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Courtney Trouble

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bisexual

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Kinky

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Style Doggy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Futanari

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Style Doggy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Prolapsed

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Orgy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pedobear

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dommes

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fantasies

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: How To Kill

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cumming

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Schlong

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fudge Packer

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Schoolgirl

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Strapon

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Anal

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Butthole

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jizz

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Creampie

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ass

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dog Style

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Lovers

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: I Hate

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Twat

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Yiffy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hedop

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rapping Women

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Domination

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Submissive

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Date Rape

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Female Squirting

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fudge Packer

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Twinkie

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tainted Love

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Orgasm

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gay Sex

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Paris Hilton

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Preteen

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Amateur

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fudge Packer

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nambla

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sadie Lune

Bet365 Зеркало – ставки на спорт в междунарожной букмекерской конторе. Вход и регистрация на русском языке.

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nigger

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Blonde Action

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jacobs Ladder Piercing

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gay

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sex

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: How To Murder

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Piss Pig

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Honkey

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bastardo

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Spic

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jizz

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nina Hartley

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nsfw Images

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fudge Packer

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Twat

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gay Men

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cazzo nella Vagina

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Aryan

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Leather Straight Jacket

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Panty

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bisexual

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pisspig

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cock

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Goatcx

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Raping

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pissing

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tainted Love

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Murder

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sexy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Leather Restraint

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pubes

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Are Idiots

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Lsd

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pubes

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pussy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Big Knockers

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Foto Gay

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rectum

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tranny

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tainted Love

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Wartenberg Pinwheel

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dommes

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Amateur

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sesso a pagamento

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Scopate

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hairy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Preteen

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Vibrator

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Philip Kindred Dick

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Happy Slapping Video

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Carpetmuncher

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sasha Grey

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fuck

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Penis

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Vibrator

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jailbait

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nig Nog

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Adult

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Babeland

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shaved Beaver

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Beaver Lips

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Deepthroat

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jesse Jane

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pole Smoker

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Twink

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Donne Nude

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Autoerotic

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Futanari

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Yellow Showers

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cream Pie

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Traci Lords

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fudge Packer

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Raghead

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Goregasm

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Spunky Teens

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shar Rednaur

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gringo

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Doggystyle

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fapserver

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Prince Albert Piercing

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Spooge

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Penis

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tentacle

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Blonde Action

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Xx

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Suck

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Twink

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bastinado

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Deepthroat

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Camel Toe

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shaved Beaver

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Yellow Showers

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sultry Women

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Carpetmuncher

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Freeones

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ball Sucking

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Titties

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dildo

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Seduced

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Incest

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hand Job

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: R@Ygold

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Kinkster

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bestiality

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cunt

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Male Squirting

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ball Licking

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: New Pornographers

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ecchi

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Smells Like Teen Spirit

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Twink

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dommes

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Babes In Toyland

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Wet Dream

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shaved Beaver

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Guro

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Babeland

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Blonde Action

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fudge Packer

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hooker

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Carpetmuncher

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Autoerotic

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Genitals

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Strapon

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Spic

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Two Girls

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ecchi

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Smells Like Teen Spirit

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gang Bang

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Savage Love

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gay Man

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Anus

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gay

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Donne Nude

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Feltch

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Babeland

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Black Cock

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Homoerotic

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Webcam

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tongue In A

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Naked

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ass

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Seduced

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Happy Slapping Video

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Throating

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tranny

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bangbros

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jackie Strano

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Stickam Girl

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Poof

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cumming

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shrimping

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Two Girls

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Serviture

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Violet Wand

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Redtube

That is really fascinating, You’re an overly professional blogger. I have joined your feed and sit up for in the hunt for extra of your magnificent post. Also, I have shared your website in my social networks!

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Violet Wand

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Two Girls One Cup

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Undressing

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Brown Showers

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cazzo in culo

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Kinkster

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Paedophile

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cleveland Steamer

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Raghead

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: 4Chan

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Poof

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bbw

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Smells Like Teen Spirit

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pegging

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Lesbian

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Anus

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Snowballing

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Boob

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hardcore

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Transexual

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tushy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Busty

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bestiality

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Yiffy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hate

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bianca Beauchamp

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: New Pornographers

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bulldyke

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Missionary Position

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Strip Club

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Kama

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jenna Jameson

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Madison Young

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rectum

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rosy Palm And Her 5 Sisters

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shanna Katz

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pussy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Kinkster

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Coprophilia

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Booty Call

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Blow Your L

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rapist

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Acrotomophilia

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nympho

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jackie Strano

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Electrotorture

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Strap On

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Orgasm

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Wank

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Naughty

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hate

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Blue Waffle

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rapping Women

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sultry Women

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Smells Like Teen Spirit

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fapserver

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Swastika

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Wet Dream

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Happy Slapping Video

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fuck

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bimbos

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cumming

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Barenaked Ladies

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Arsehole

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Motherfucker

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Foto Gay

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fuck Buttons

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Seduced

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Interracial

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Assmunch

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bulldyke

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Slit

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Paedophile

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Chocolate Rosebuds

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Squirt

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Spunky Teens

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jordan Capri

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Naughty

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Group Sex

There are some interesting cut-off dates on this article however I don’t know if I see all of them heart to heart. There’s some validity however I’ll take maintain opinion till I look into it further. Good article , thanks and we want more! Added to FeedBurner as effectively

I dugg some of you post as I cogitated they were handy extremely helpful

I would like to thank you for the efforts you’ve put in writing this website. I am hoping the same high-grade web site post from you in the upcoming also. In fact your creative writing skills has inspired me to get my own blog now. Really the blogging is spreading its wings fast. Your write up is a good example of it.

An interesting discussion is worth comment. I think that you should write more on this topic, it might not be a taboo subject but generally people are not enough to speak on such topics. To the next. Cheers

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Femdom

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ducky Doolittle

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Betty Dodson

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Domination

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Paris Hilton

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Honkey

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tea Bagging

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Mr Hands

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Naughty

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Goodvibes

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cuckold

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Camel Toe

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Linda Lovelace

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Raging Boner

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Juggs

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jesse Jane

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bestiality

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bung Hole

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Porno

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Webcam

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Titties

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ball Kicking

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Faggot

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Asshole

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Taste My

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Figging

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nymphomania

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nymphomania

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rosy Palm And Her 5 Sisters

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Muffdiving

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bunghole

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tentacle

Very good written article. It will be valuable to anyone who usess it, including me. Keep doing what you are doing – can’r wait to read more posts.

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dirty Sanchez

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Muff Diver

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hand Job

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Blow J

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pole Smoker

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Goodpoop

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Muff Diver

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shar Rednaur

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Double Penetration

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sodomy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fetish

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Kama

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fuck Buttons

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ball Kicking

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Redtube

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bianca Beauchamp

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Barenaked Ladies

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Anal

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pisspig

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Poopchute

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Seduced

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Poopchute

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Suicide Girls

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Figging

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rectum

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Black Cock

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nambla

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Webcam

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: 4Chan

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dirty Sanchez

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jackie Strano

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Blow J

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Blonde Action

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Submissive

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Yaoi

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Girls Gone Wild

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nonconsent

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Reverse Cowgirl

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Baby Batter

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nambla

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tub Girl

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Violet Wand

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bangbros

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hate

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Female Squirting

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cunnilingus

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gay Sex

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Beaver Cleaver

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rapist

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Incest

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Assmunch

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Linda Lovelace

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Electrotorture

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dirty Sanchez

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Undressing

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Poopchute

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: John Holmes

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Penis

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bisexual

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gay Sex

I like your writing style truly loving this web site.

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Grope

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Stormfront

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nipples

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Redtube

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Kike

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Carol Queen

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Vibrator

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ragazze Nude

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Paedophile

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sadie Lune

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Lovemaking

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tubgirl

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Titty

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Babeland

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jizz

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gang Bang

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Reverse Cowgirl

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Camgirl

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ass

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Urethra Play

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bbw

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Snowballing

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Leather Restraint

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Coprophilia

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jailbait

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Humping

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Donne Nude

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Women Rapping

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shrimping

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gringo

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Vibrator

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Leather Restraint

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Blow Your L

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hentai

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Raping

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Playboy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shar Rednaur

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shibari

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Male Squirting

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bondage

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Giant Cock

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bollocks

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ponyplay

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hairy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Women Rapping

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sexy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Mdma

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Anal

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: One Cup Two Girls

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sucks

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Arsehole

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nympho

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Butt

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Blonde Action

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Beaver Cleaver

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fuck

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Frotting

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tied Up

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Vulva

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Clover Clamps

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shaved Beaver

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Wank

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Vibrator

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ball Gravy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Schoolgirl

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Guro

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Queaf

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fingering

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Madison Young

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: New Pornographers

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Piece Of Shit

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Slut

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fuck

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Clover Clamps

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Smells Like Teen Spirit

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tubgirl

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Lsd

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ass

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: How To Murder

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Savage Love

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Schlong

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Boob

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pre Teen

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jack Off

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bianca Beauchamp

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Foto Porno

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Kinkster

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Girls Gone Wild

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Towelhead

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tentacle

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gay Sex

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Urethra Play

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hookup

I’m not that much of a online reader to be honest but your blogs really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your site to come back down the road. Many thanks

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Wartenberg Wheel

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Strappado

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Coprophilia

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: S&M

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Panties

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Paris Hilton

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Mr Hands

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: White Power

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gay

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Murder

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Chastity Belt

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Spank

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sesso a pagamento

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Barenaked Ladies

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Twat

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pedobear

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Threesome

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Motherfucker

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Wrapping Men

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Group Sex

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sultry Women

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hedop

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: G-Spot

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Lesbian

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sultry Women

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jigaboo

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Big Black

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rosy Palm

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Consensual Intercourse

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bollocks

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tit

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Juggs

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Foto Gay

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Stileproject

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Paris Hilton

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Teen

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shanna Katz

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rapping Women

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Piece Of Shit

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Omorashi

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Amateur

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Electrotorture

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Two Girls One Cup

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cum

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Crossdresser

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bianca Beauchamp

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tosser

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jail Bait

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fetish

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Penis

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Schoolgirl

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Immagini Porno

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cream Pie

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Coprolagnia

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Clitoris

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sexy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Butt

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Camel Toe

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Make Me Come

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tit

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Busty

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Figging

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Reverse Cowgirl

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fuck Buttons

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cum

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Spunky Teens

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hot Chick

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rusty Trombone

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ball Gag

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Swastika

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hand Job

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Blow Your L

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dirty Sanchez

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fantasies

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Tight White

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Clit

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Swastika

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gay Boy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rapping Women

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Kama

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ragazze Nude

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Swinger

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Femdom

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Porn

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fudge Packer

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Erotic

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shota

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Autoerotic

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cocks

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jesse Jane

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Omorashi

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Two Girls

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Faggot

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Suicide Girls

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Female Squirting

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Buttcheeks

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Trans

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Two Girls One Cup

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Goregasm

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Snowballing

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bestiality

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Xx

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Felch

Howdy! I know this is kind of off topic but I was wondering which blog platform are you using for this website? I’m getting tired of WordPress because I’ve had problems with hackers and I’m looking at options for another platform. I would be fantastic if you could point me in the direction of a good platform.

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: G-Spot

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Spic

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hate

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rectum

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Chrissie Wunna

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bulldyke

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sexo

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ponyplay

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Deep Throat

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Squirt

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shaved Pussy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nympho

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: White Power

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Goatcx

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Reverse Cowgirl

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Doggie Style

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Foot Fetish

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nina Hartley

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dominatrix

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Vibrator

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Mr Hands

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sexy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Circlejerk

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Poop Chute

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Xx

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bareback

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Strapon

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Freeones

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: A2M

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Knobbing

I’m not sure why but this web site is loading very slow for me. Is anyone else having this problem or is it a issue on my end? I’ll check back later on and see if the problem still exists.

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: 4Chan

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ragazze Nude

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Baby Batter

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Asshole

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pedophile

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Doggy Style

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Redtube

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Autoerotic

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jordan Capri

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ponyplay

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Redtube

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Boner

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gay Man

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Panties

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rape

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Doggystyle

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Juggs

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Urethra Play

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Submissive

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Betty Dodson

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Babeland

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Barenaked Ladies

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Neonazi

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Carpetmuncher

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ball Kicking

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Sodomy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Kama

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shaved Pussy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Lingerie

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Lsd

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Xx

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Foto di Puttane

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pussy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rectum

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jigaboo

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Deepthroat

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bimbos

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nambla

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Snowballing

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Blonde On Blonde Action

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Kike

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Rimjob

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Dirty Pillows

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Phone Sex

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Transexual

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Puttane

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Urophilia

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Slut

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: A2M

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Get My Sister

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Amateur

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Upskirt

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Blonde On Blonde Action

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ball Gravy

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: 4Chan

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Wartenberg Pinwheel

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Jenna Jameson

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pubes

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Hate

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Anilingus

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Gang Bang

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Shibari

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Poopchute

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Threesome

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Mound Of Venus

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pamela Anderson

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Bi Curious

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Golden Shower

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Swastika

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Violet Wand

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Pubes

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Scopate

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Butthole

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Panties

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Nsfw Images

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Domination

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Fudge Packer

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Feltch

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Transexual

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Prince Albert Piercing

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Missionary Position

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: How To Murder

I simply desired to thank you so much again. I am not sure the things I could possibly have created in the absence of the entire advice discussed by you on that subject matter. It actually was a difficult situation for me personally, however , considering a skilled approach you handled that made me to jump with happiness. I’m just grateful for this support and thus pray you realize what a great job you have been accomplishing teaching people today thru your web page. I am sure you haven’t encountered all of us.

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Lolita

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Blonde On Blonde Action

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Cleveland Steamer

Mi piace troppo la sborra in bocca: Ball Sucking