Thapelo Mokoatsi

The Secrecy Bill, first surfaced in South Africa in the 1820s in the Cape Colony, under the authoritarian British colonial Governor, Lord Charles Somerset, whose sole purpose was to clamp down on Freedom of the Press.

Somerset’s targeted efforts to strictly regulate press and protests were directed at Scots settler duo journalists and newspaper men – Thomas Pringle and John Fairbairn. During one of his numerous meetings with Pringle, he responded to an editorial published in the colony’s English-language periodical, the South African Journal. Interpreting it as a personal attack, he said to Pringle:

“‘So, sir!’ he began – you are one of those who dare to insult me, and oppose my government!”

– Colonial Office, May 18, 1824.

By this time Pringle and Fairbairn, who were joined at the hip had founded and edited the first English-language magazine South African Journal and newspaper South African Commercial Advertiser. Pringle, in the journal, had carried content that opened up discussions on Free Press in South Africa. He had called for an open discussion of different means of a Free Press, its liberty (not licentiousness) in the South African Journal, 7 April, 1824. Just a month before he was invited to the un-ceremonial meeting at the Colonial Office, to appear before Somerset and the Chief Justice, Sir John Truter, to justify publishing an article that lamented the conditions of the settlers.

In it he had criticised Somerset’s treatment of Albany settlers and his ‘commando’ raids across the eastern frontier. In defiance of being regulated Pringle chose to close down the South African Journal rather than submit to what he deemed official censorship but continued to work with Fairbairn at the South African Commercial Advertiser, a position he would also give up due to pressure from Somerset. He did however leave a legacy.

The formative years of Pringle

Pringle was born into a farming family in Scotland in 1789, and sustained an injury when he was accidentally dropped by his nanny when he was only three months old. The injury meant that he could not follow the family tradition of farming, so his father sent him to Kelso Grammar School and Edinburgh University where he developed an interest in writing.

Thomas Pringle

Image courtesy of sahistory.org.za

He did however leave Edinburgh without obtaining a degree, but left with a talent to write poetry which won him acclaim in high places. He immigrated to South Africa with his family in 1820, to make home in Glen Lynden, located in the upper valley of South Africa’s Baviaans River. It took two years for Pringle, his father, and the rest of the family to establish the family homestead, which eventually comprised 20 000 acres of land.

As he had done prior to the family’s travelling to South Africa, Pringle served as the family spokesperson and conferred with government and military officials. His influence helped the family succeed in South Africa whereas many other immigrants did not. After his family was settled Pringle himself moved to Cape Town, where he worked in the newly created South African Public Library, a job Governor Somerset helped secure for him. He also continued to pursue his writing career. Realising that his small income from the library needed to be supplemented, he persuaded his fellow Scotsman, John Fairbairn to join him in Cape Town in 1822, promising a literary and teaching career in the recently annexed Cape Colony. Fairbairn arrived in Table Bay on 11 October 1823 aboard the brig Mary. With Pringle, they opened a school and established two publications – South Africa Journal and South African Commercial Advertiser, southern Africa’s first independent newspaper.

The struggles of Free Press Advocacy

Fairbairn, had an impeccable background himself, he had attended the University of Edinburgh where he studied Medicine “acquiring at the same time a more than passing knowledge of classical languages and mathematics.” In 1818, however, he turned to education, and for more than five years taught at Bruce’s Academy in Newcastle upon Tyne, where he joined the Literary and Philosophical Society. He couldn’t have made a better choice to partner with Pringle, as the duo, through their publications began what would become years of struggle with the authorities for a free press. Their editorship of the South African Journal and The South African Commercial Advertiser, led to clashes with authorities as they published material that was not approved by authorities. Pringle rejected the idea of free press as a privilege in the power of governments, and his claim was unequivocal that it is a natural right of a free man. He was willing to risk personal prospects, and obstinately resisted authority which included his decision to close the Journal. Although the Governor continued to invite him to recommence the journal, he refused saying it would not be republished unless legal protection was granted to the press. This would result in his resignation as a sub-librarian. He left South Africa and returned to Britain in 1826. His efforts and those of his fellow Scotsman were to be the foundation upon which English and Afrikaans newspapers, then unborn, were to be built. He just never lived to see it succeed.

Fairbairn held on to their shared belief that to collaborate with a controlled press would compromise the liberties of people. He however expressed a priest-like, colonial missionary moral stance, dedicating his contribution to God and his country, writing in September 1825:

“…we are indebted to two of the most illustrious inventions with which God has been pleased to reward the ingenuity and perseverance of man, and for which our gratitude should only be second in degree to our thankfulness for the Revelation of Christ and the hopes of immortality.”

He later wrote in the same year:

“We are responsible to God and our Country for everything we permit to pass into our pages …”

Fruits of obstinacy

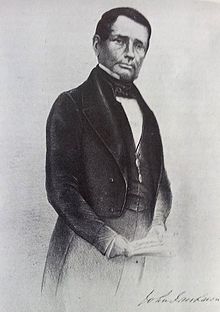

John Fairbairn

Fairbairn continued to fight for Press freedom. His efforts paid off when in April/May 1829 the Cape Colonial government gave an undertaking to guarantee the freedom of the press. This change of heart hadn’t organically happened. Fairbairn had had to appeal to the British government to gain the right to publish without hindrance.

This led to what became known as the “Magna Carta” of press freedom in South Africa, and concerned the proclamation of Ordinance No 60, the so-called “Press Ordinance”. It is not clear when it was promulgated but it took effect on May 15. Though it had limitations – Fairbairn accepted, and is today one of the honoured names in the history of press freedom in our country. Pringle had at that time moved on from being a poet, educator and newspaperman to being an abolitionist.

Their last days

Pringle drowning in debt had returned and settled in London. An anti-slavery article which he had written in South Africa before he left was published in the New Monthly Magazine, and brought him to the attention of Buxton, Zachary Macaulay and others, which led to his being appointed Secretary of the Anti-Slavery Society. He began working for the Committee of the Anti-Slavery Society in March 1827, and continued for seven years. He also published African Sketches and books of poems, such as Ephemerides.

As Secretary of the Anti-Slavery Society he helped steer the organisation towards its eventual success; in 1834, with a widening of the electoral franchise. The Reformed British Parliament passed legislation to bring an end to slavery in the British dominions – the aim of Pringle’s Society. Pringle signed the Society’s notice to set aside 1 August 1834 as a religious thanksgiving for the passing of the Act. However, the legislation did not come into effect until August 1838, and Pringle was unable to witness this moment; he had died from tuberculosis in December 1834 at the age of 45. Fairbairn continued to work and would die suddenly in Cape Town in 1864 at which time, his and Pringle’s efforts had opened doors for many aspirant publishers. By 1831 newspapers were springing up away from the mother city. The Eastern Cape saw its first English newspaper – the Grahamstown Journal (1831). Today, some of the old and celebrated publications that still exist were initiated during this era – Eastern Cape Herald (1845); Natal Witness (1846); Natal Mercury (1852); The Argus (1857) and many others. In the end separating Pringle from Fairbairn stories was impossible as theirs were interwoven lives that formed a story of legacy building.

I’ve learned many important things via your post. I’d personally also like to say that there might be situation in which you will apply for a loan and don’t need a cosigner such as a National Student Aid Loan. When you are getting a borrowing arrangement through a regular bank then you need to be prepared to have a co-signer ready to make it easier for you. The lenders will probably base their own decision using a few aspects but the main one will be your credit score. There are some loan providers that will also look at your job history and decide based on that but in many cases it will hinge on your score.

Great ?I should certainly pronounce, impressed with your site. I had no trouble navigating through all the tabs and related info ended up being truly easy to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it at all. Reasonably unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or anything, site theme . a tones way for your client to communicate. Excellent task..

Along with almost everything which seems to be developing within this subject matter, a significant percentage of perspectives tend to be rather refreshing. However, I am sorry, but I can not subscribe to your entire suggestion, all be it exciting none the less. It appears to everybody that your comments are not totally justified and in reality you are your self not even fully confident of your argument. In any event I did appreciate reading through it.

Would you please add some more detail? It’s a very eloquent post though, so bless you!

I have realized that over the course of constructing a relationship with real estate owners, you’ll be able to come to understand that, in each and every real estate contract, a percentage is paid. In the end, FSBO sellers really don’t “save” the commission rate. Rather, they struggle to win the commission through doing an agent’s work. In completing this task, they devote their money as well as time to conduct, as best they’re able to, the obligations of an broker. Those tasks include revealing the home via marketing, offering the home to willing buyers, constructing a sense of buyer desperation in order to induce an offer, scheduling home inspections, dealing with qualification assessments with the financial institution, supervising maintenance, and aiding the closing of the deal.

My coder is trying to convince me to move to .net from PHP. I have always disliked the idea because of the costs. But he’s tryiong none the less. I’ve been using Movable-type on various websites for about a year and am nervous about switching to another platform. I have heard excellent things about blogengine.net. Is there a way I can import all my wordpress content into it? Any help would be really appreciated!

Hello, you used to write excellent, but the last few posts have been kinda boring?I miss your super writings. Past several posts are just a little out of track! come on!

Today, with all the fast life style that everyone is having, credit cards have a big demand throughout the market. Persons out of every field are using the credit card and people who not using the card have arranged to apply for just one. Thanks for expressing your ideas on credit cards.

Thanks for your information on this blog. One particular thing I would want to say is purchasing electronic products items from the Internet is certainly not new. In fact, in the past several years alone, the market for online electronic devices has grown considerably. Today, you can find practically virtually any electronic gadget and other gadgets on the Internet, ranging from cameras and camcorders to computer parts and game playing consoles.

Through my research, shopping for electronic products online can for sure be expensive, but there are some principles that you can use to help you get the best things. There are often ways to come across discount discounts that could help make one to buy the best technology products at the cheapest prices. Great blog post.

Please provide me with more details on the topic

Thanks for posting. I really enjoyed reading it, especially because it addressed my problem. It helped me a lot and I hope it will help others too.

Thank you for your articles. They are very helpful to me. Can you help me with something?

May I request that you elaborate on that? Your posts have been extremely helpful to me. Thank you!

You helped me a lot by posting this article and I love what I’m learning.

You’ve the most impressive websites.

Thank you for your post. I really enjoyed reading it, especially because it addressed my issue. It helped me a lot and I hope it will also help others.

Great content! Super high-quality! Keep it up!

Admiring the commitment you put into your site and detailed information you offer. It’s good to come across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the same outdated rehashed material. Wonderful read! I’ve bookmarked your site and I’m including your RSS feeds to my Google account.

Thank you for sharing this article with me. It helped me a lot and I love it.

May I request more information on the subject? All of your articles are extremely useful to me. Thank you!

Can you write more about it? Your articles are always helpful to me. Thank you!

Please tell me more about this. May I ask you a question?

Please tell me more about this. May I ask you a question?

Great beat ! I would like to apprentice while you amend your web site, how could i subscribe for a blog site? The account helped me a acceptable deal. I had been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast provided bright clear concept

Thanks for posting. I really enjoyed reading it, especially because it addressed my problem. It helped me a lot and I hope it will help others too.

Thank you for writing this article. I appreciate the subject too.

Thank you for your post. I really enjoyed reading it, especially because it addressed my issue. It helped me a lot and I hope it will also help others.

Good V I should definitely pronounce, impressed with your site. I had no trouble navigating through all tabs and related info ended up being truly simple to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it at all. Quite unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or something, website theme . a tones way for your customer to communicate. Excellent task..

May I request more information on the subject? All of your articles are extremely useful to me. Thank you!

Thanks, I have recently been looking for information approximately this subject for ages and yours is the best I have discovered so far. However, what about the bottom line? Are you positive about the supply?

Greetings! Very helpful advice on this article! It is the little changes that make the biggest changes. Thanks a lot for sharing!

you will have an amazing weblog right here! would you prefer to make some invite posts on my weblog?

You really make it seem so easy with your presentation but I find this matter to be really something which I think I would never understand. It seems too complex and extremely broad for me. I am looking forward for your next post, I will try to get the hang of it!

I?¦ve recently started a website, the information you provide on this site has helped me tremendously. Thanks for all of your time & work.

Thanks for sharing superb informations. Your website is very cool. I’m impressed by the details that you’ve on this web site. It reveals how nicely you understand this subject. Bookmarked this web page, will come back for extra articles. You, my pal, ROCK! I found just the information I already searched everywhere and just couldn’t come across. What a perfect web-site.

I like what you guys are up also. Such clever work and reporting! Carry on the excellent works guys I’ve incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it’ll improve the value of my site :).

Dead written content material, Really enjoyed examining.

You have mentioned very interesting points! ps decent internet site.

I truly appreciate this post. I have been looking all over for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You’ve made my day! Thanks again!

I like this website very much, Its a really nice post to read and find information.

Pretty great post. I simply stumbled upon your weblog and wanted to say that I have really loved browsing your blog posts. After all I’ll be subscribing for your feed and I am hoping you write once more very soon!

Nice read, I just passed this onto a friend who was doing some research on that. And he just bought me lunch since I found it for him smile Thus let me rephrase that: Thank you for lunch! “How beautiful maleness is, if it finds its right expression.” by D. H. Lawrence.

Lovely site! I am loving it!! Will come back again. I am taking your feeds also

Hello.This article was really fascinating, especially because I was searching for thoughts on this matter last couple of days.

Your articles are extremely helpful to me. Please provide more information!

Appreciate it for this terrific post, I am glad I found this website on yahoo.

May I have information on the topic of your article?

I would like to thnkx for the efforts you’ve put in writing this website. I am hoping the same high-grade blog post from you in the upcoming also. Actually your creative writing abilities has encouraged me to get my own blog now. Really the blogging is spreading its wings fast. Your write up is a great example of it.

Please tell me more about your excellent articles

I like the valuable information you provide in your articles. I’ll bookmark your weblog and check again here frequently. I’m quite sure I will learn many new stuff right here! Best of luck for the next!

Thank you for your articles. They are very helpful to me. Can you help me with something?

Great beat ! I would like to apprentice while you amend your web site, how could i subscribe for a blog site? The account helped me a acceptable deal. I had been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast provided bright clear concept

You really make it seem really easy with your presentation but I in finding this topic to be actually one thing which I believe I would by no means understand. It kind of feels too complex and extremely broad for me. I am looking ahead on your subsequent submit, I¦ll attempt to get the cling of it!

You can definitely see your expertise in the work you write. The world hopes for more passionate writers like you who aren’t afraid to say how they believe. Always go after your heart.

Great content! Super high-quality! Keep it up!

It is truly a great and helpful piece of information. I¦m glad that you shared this useful information with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

Your articles are very helpful to me. May I request more information?

I don’t ordinarily comment but I gotta state thankyou for the post on this special one : D.

With havin so much written content do you ever run into any problems of plagorism or copyright violation? My blog has a lot of exclusive content I’ve either written myself or outsourced but it seems a lot of it is popping it up all over the web without my permission. Do you know any ways to help prevent content from being stolen? I’d really appreciate it.

The articles you write help me a lot and I like the topic

hello there and thank you for your info – I’ve definitely picked up anything new from right here. I did however expertise several technical points using this site, as I experienced to reload the website lots of times previous to I could get it to load properly. I had been wondering if your web host is OK? Not that I am complaining, but sluggish loading instances times will often affect your placement in google and could damage your high-quality score if advertising and marketing with Adwords. Anyway I am adding this RSS to my email and can look out for much more of your respective fascinating content. Ensure that you update this again very soon..

I don’t even know how I finished up here, but I thought this put up was great. I do not know who you might be however certainly you are going to a well-known blogger if you are not already 😉 Cheers!

May I request more information on the subject? All of your articles are extremely useful to me. Thank you!

Simply a smiling visitor here to share the love (:, btw great design and style.

You have observed very interesting points! ps decent website .

I do love the way you have presented this situation and it really does supply me a lot of fodder for thought. Nevertheless, through what precisely I have experienced, I basically hope when the reviews pile on that individuals stay on point and in no way embark on a tirade involving some other news of the day. Still, thank you for this superb piece and though I can not concur with this in totality, I value your perspective.

superb post.Ne’er knew this, appreciate it for letting me know.

I haven?¦t checked in here for some time since I thought it was getting boring, but the last several posts are great quality so I guess I will add you back to my daily bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

Valuable info. Lucky me I found your web site by accident, and I am shocked why this accident didn’t happened earlier! I bookmarked it.

Get-X – онлайн игра с реальным выводом средств. В неё входят азартные игры, где можно делать ставки, например, Краш.

Great post. I am facing a couple of these problems.

Hi there very nice blog!! Man .. Beautiful .. Amazing .. I will bookmark your web site and take the feeds additionally?KI am happy to find a lot of helpful information here in the submit, we want work out more strategies on this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

I have been exploring for a little for any high-quality articles or weblog posts on this kind of area . Exploring in Yahoo I finally stumbled upon this web site. Studying this information So i?¦m happy to convey that I have a very excellent uncanny feeling I found out exactly what I needed. I most no doubt will make sure to do not put out of your mind this web site and give it a look regularly.

Thank you for your articles. They are very helpful to me. May I ask you a question?

May I have information on the topic of your article?

I am glad to be one of many visitants on this great web site (:, appreciate it for putting up.

May I have information on the topic of your article?

Aw, this was a very nice post. In idea I want to put in writing like this moreover – taking time and actual effort to make a very good article… but what can I say… I procrastinate alot and certainly not seem to get something done.

I visited a lot of website but I believe this one has something extra in it in it

Only wanna admit that this is very beneficial, Thanks for taking your time to write this.

I went over this web site and I conceive you have a lot of fantastic info, saved to my bookmarks (:.

Howdy! This post could not be written any better! Reading this post reminds me of my previous room mate! He always kept chatting about this. I will forward this article to him. Pretty sure he will have a good read. Many thanks for sharing!

I have learn some just right stuff here. Definitely price bookmarking for revisiting. I surprise how a lot effort you place to create this sort of great informative website.

hi!,I really like your writing so a lot! proportion we be in contact extra approximately your article on AOL? I require a specialist on this space to resolve my problem. Maybe that is you! Having a look forward to look you.

Along with every thing which appears to be building within this subject material, many of your points of view are actually fairly radical. Even so, I am sorry, because I do not subscribe to your whole idea, all be it exhilarating none the less. It would seem to us that your remarks are actually not entirely justified and in actuality you are yourself not completely certain of your point. In any case I did take pleasure in looking at it.

I just could not depart your site prior to suggesting that I really loved the standard information a person provide in your guests? Is gonna be back frequently to check out new posts.

I’m still learning from you, as I’m improving myself. I absolutely liked reading all that is written on your site.Keep the information coming. I liked it!

Currently it appears like Movable Type is the preferred blogging platform out there right now. (from what I’ve read) Is that what you are using on your blog?

Hi there, simply was aware of your weblog via Google, and located that it is truly informative. I’m going to be careful for brussels. I will be grateful for those who continue this in future. Many folks can be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

Perfect piece of work you have done, this site is really cool with wonderful info .

Someone essentially help to make seriously articles I would state. This is the first time I frequented your web page and thus far? I amazed with the research you made to create this particular publish amazing. Wonderful job!

I am glad to be one of many visitants on this outstanding internet site (:, thankyou for putting up.

I love your great takeaways. Do you think that I can integrate it alongside quicktrafficsoftware.com

I’m really enjoying the design and layout of your blog. It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more pleasant for me to come here and visit more often. Did you hire out a designer to create your theme? Fantastic work!

I have been examinating out many of your articles and i can claim pretty good stuff. I will definitely bookmark your website.

I love the efforts you have put in this, thanks for all the great articles.

What i don’t understood is if truth be told how you’re now not really a lot more neatly-appreciated than you might be right now. You’re so intelligent. You already know therefore considerably with regards to this matter, produced me for my part believe it from numerous numerous angles. Its like men and women aren’t interested unless it is one thing to accomplish with Girl gaga! Your individual stuffs nice. All the time take care of it up!

I haven¦t checked in here for a while as I thought it was getting boring, but the last few posts are great quality so I guess I will add you back to my daily bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

Very interesting details you have remarked, thanks for putting up. “The surest way to get rid of a bore is to lend money to him.” by Paul Louis Courier.

Hmm it looks like your website ate my first comment (it was extremely long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I submitted and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I as well am an aspiring blog writer but I’m still new to the whole thing. Do you have any tips and hints for beginner blog writers? I’d certainly appreciate it.

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

Thanks for the sensible critique. Me and my neighbor were just preparing to do some research about this. We got a grab a book from our local library but I think I learned more from this post. I’m very glad to see such excellent information being shared freely out there.

Hey! Check this site full of deals!

https://www.amazoniadeals.com

Nice post. I learn something more challenging on different blogs everyday. It will always be stimulating to read content from other writers and practice a little something from their store. I’d prefer to use some with the content on my blog whether you don’t mind. Natually I’ll give you a link on your web blog. Thanks for sharing.

I do not even know how I ended up here, but I thought this post was good. I don’t know who you are but definitely you’re going to a famous blogger if you aren’t already 😉 Cheers!

I¦ve learn a few just right stuff here. Certainly value bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how so much effort you set to create such a excellent informative website.

Great beat ! I would like to apprentice while you amend your web site, how could i subscribe for a blog site? The account helped me a acceptable deal. I had been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast provided bright clear concept

An impressive share, I just given this onto a colleague who was doing a little analysis on this. And he in fact bought me breakfast because I found it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the treat! But yeah Thnkx for spending the time to discuss this, I feel strongly about it and love reading more on this topic. If possible, as you become expertise, would you mind updating your blog with more details? It is highly helpful for me. Big thumb up for this blog post!

Very clean website , thankyou for this post.

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information. Your website is very useful. Thanks for sharing.

Beli 4D Online | Magnum | Sport Toto | Da ma cai | Singapore Lotto | Grand Dragon Lotto | Sandakan 4D | CashSweep | Sabah 88 | 9 Lotto | Buy 4d online | 4D Nombor di https://bit.ly/cm4d-web

I must show some thanks to this writer just for rescuing me from this type of instance. Just after exploring through the world wide web and getting ideas which were not productive, I thought my entire life was done. Living devoid of the strategies to the problems you have sorted out by way of your good short post is a crucial case, as well as those which may have in a negative way damaged my entire career if I had not discovered your blog. Your main training and kindness in maneuvering all the things was important. I don’t know what I would’ve done if I hadn’t encountered such a step like this. I can at this point relish my future. Thanks so much for the specialized and results-oriented help. I won’t think twice to suggest the sites to anybody who should receive care about this subject matter.

It’s really a cool and helpful piece of info. I’m glad that you shared this helpful information with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

Simply desire to say your article is as astonishing. The clearness for your submit is simply nice and that i can think you are a professional on this subject. Well with your permission allow me to take hold of your RSS feed to keep up to date with drawing close post. Thank you one million and please carry on the gratifying work.

Some genuinely prime blog posts on this website , saved to bookmarks.

hello there and thanks for your information – I’ve certainly picked up something new from right here. I did then again expertise some technical points using this website, since I experienced to reload the web site lots of instances previous to I may just get it to load properly. I were wondering if your web hosting is OK? No longer that I am complaining, but sluggish loading cases occasions will very frequently have an effect on your placement in google and can injury your high quality rating if advertising and ***********|advertising|advertising|advertising and *********** with Adwords. Well I’m adding this RSS to my email and can glance out for a lot extra of your respective intriguing content. Make sure you replace this once more soon..

Wonderful beat ! I wish to apprentice while you amend your website, how could i subscribe for a blog web site? The account aided me a appropriate deal. I had been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast provided bright transparent idea

I view something genuinely special in this internet site.

You could certainly see your skills in the work you write. The world hopes for even more passionate writers like you who aren’t afraid to say how they believe. Always follow your heart.

WONDERFUL Post.thanks for share..extra wait .. …

Thanks, I have recently been searching for information about this subject for a long time and yours is the best I have discovered till now. But, what concerning the conclusion? Are you certain in regards to the source?

I’ve read a few excellent stuff here. Certainly price bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how a lot effort you set to create one of these excellent informative web site.

Good day I am so grateful I found your webpage, I really found you by accident, while I was looking on Askjeeve for something else, Anyways I am here now and would just like to say many thanks for a incredible post and a all round entertaining blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to browse it all at the minute but I have book-marked it and also included your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read much more, Please do keep up the excellent job.

Thank you for your articles. They are very helpful to me. Can you help me with something?

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain nice points in features also.

4D Online | Magnum | Sport Toto | Da ma cai | Singapore Lotto | Grand Dragon Lotto | Sandakan 4D | CashSweep | Sabah

whoah this blog is fantastic i like reading your articles. Stay up the good paintings! You recognize, many persons are hunting round for this info, you could aid them greatly.

Your articles are extremely helpful to me. Please provide more information!

Attractive section of content. I just stumbled upon your blog and in accession capital to assert that I acquire in fact enjoyed account your blog posts. Any way I’ll be subscribing to your augment and even I achievement you access consistently fast.

You have brought up a very fantastic points, regards for the post.

Hello. Great job. I did not imagine this. This is a excellent story. Thanks!

Can I just say what a relief to find someone who actually knows what theyre talking about on the internet. You definitely know how to bring an issue to light and make it important. More people need to read this and understand this side of the story. I cant believe youre not more popular because you definitely have the gift.

You are a very bright person!

Regards for all your efforts that you have put in this. very interesting information.

Thank you for helping out, good info. “The laws of probability, so true in general, so fallacious in particular.” by Edward Gibbon.

I love the efforts you have put in this, thank you for all the great blog posts.

Your blog is always so well-written and engaging, thank you.

You are my breathing in, I own few web logs and occasionally run out from post :). “No opera plot can be sensible, for people do not sing when they are feeling sensible.” by W. H. Auden.

Thank you for being εφαρμογή για περπατημα στα ελληνικά δωρεάν a reliable source of information.

Your blog is always so informative and interesting, thank you.

Spot on with this write-up, I actually assume this web site wants far more consideration. I’ll in all probability be again to learn much more, thanks for that info.

Thank you for being such a great storyteller through your blog.

I think other website owners should take this web site as an model, very clean and wonderful user genial style.

I have read several excellent stuff here. Certainly price bookmarking for revisiting. I surprise how a lot effort you put to create this sort of magnificent informative website.

Hey, you used to write wonderful, but the last few posts have been kinda boringK I miss your great writings. Past few posts are just a little out of track! come on!

Good V I should certainly pronounce, impressed with your website. I had no trouble navigating through all tabs as well as related info ended up being truly easy to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it in the least. Quite unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or anything, website theme . a tones way for your customer to communicate. Excellent task..

It’s exhausting to find educated people on this matter, but you sound like you recognize what you’re talking about! Thanks

Utterly composed written content, regards for selective information.

great put up, very informative. I’m wondering why the other experts of

this sector do not notice this. You must proceed your writing.

I am confident, you’ve a great readers’ base already!

This post gave me a new perspective on [insert topic]. Thanks for broadening my horizons.

Your style is so unique compared to many other people. Thank you for publishing when you have the opportunity,Guess I will just make this bookmarked.2

This post gave me a new perspective on [insert topic]. Thanks for broadening my horizons.

It’s really a nice and useful piece of info. I’m glad that you shared this helpful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

Great post! You really hit the nail on the head with this one.

I appreciate the time and effort you put into creating this content. It’s very informative.

I just wanted to drop by and say how much I enjoy your blog. Keep up the great work!

Hi , I do believe this is an excellent blog. I stumbled upon it on Yahoo , i will come back once again. Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and help other people.

I really wanted to write down a quick comment in order to appreciate you for those fantastic solutions you are giving at this site. My time intensive internet search has finally been paid with incredibly good facts to share with my good friends. I would express that many of us visitors actually are very blessed to exist in a useful community with many outstanding individuals with valuable solutions. I feel truly grateful to have come across the site and look forward to plenty of more entertaining times reading here. Thanks a lot once more for all the details.

I wanted to thank you for this great read!! I definitely enjoying every little bit of it I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you post…

I appreciate, cause I found just what I was looking for. You’ve ended my 4 day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a nice day. Bye

I’d have to verify with you here. Which is not one thing I usually do! I take pleasure in studying a submit that can make people think. Also, thanks for allowing me to remark!

Good day I am so glad I found your webpage, I really found you by accident, while I was researching on Askjeeve for something else, Regardless I am here now and would just like to say thanks a lot for a remarkable post and a all round entertaining blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to read it all at the minute but I have book-marked it and also included your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read more, Please do keep up the great work.

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It if truth be told was a leisure account it. Look complex to more added agreeable from you! By the way, how could we communicate?

I’m not sure the place you are getting your info, however great topic. I needs to spend a while finding out much more or working out more. Thank you for great info I used to be in search of this info for my mission.

Hello. Great job. I did not imagine this. This is a remarkable story. Thanks!

ラブドール tpe これがフォーマットの問題なのか、インターネットブラウザの互換性と関係があるのかはわかりませんが、投稿してお知らせしたいと思います。

After examine a number of of the weblog posts in your website now, and I actually like your means of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website listing and can be checking again soon. Pls try my website as effectively and let me know what you think.

Hi, i think that i saw you visited my website thus i came to “go back the want”.I am trying to to find things to enhance my web site!I suppose its adequate to make use of some of your ideas!!

I am not certain the place you’re getting your information, however great topic. I must spend a while finding out more or working out more. Thanks for fantastic information I used to be searching for this info for my mission.

This post gave me a new perspective on [insert topic]. Thanks for broadening my horizons.

This is exactly what I was looking for. Thanks for providing such valuable information.

Very great post. I simply stumbled upon your blog and wished to mention that I’ve really enjoyed surfing around your weblog posts. After all I will be subscribing for your feed and I am hoping you write again soon!

This post gave me a new perspective on [insert topic]. Thanks for broadening my horizons.

I likewise believe so , perfectly written post! .

I needed to put you a bit of word in order to say thanks a lot as before over the unique guidelines you have shown on this page. It’s quite strangely generous with people like you to supply freely precisely what a number of us could have supplied for an e book to make some dough for their own end, most notably considering that you might have tried it in case you desired. The suggestions additionally served to become fantastic way to recognize that someone else have similar fervor like mine to know the truth great deal more pertaining to this problem. I believe there are lots of more fun times up front for those who see your website.

Hmm it looks like your website ate my first comment (it was extremely long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I wrote and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I as well am an aspiring blog writer but I’m still new to the whole thing. Do you have any helpful hints for newbie blog writers? I’d really appreciate it.

Your blog has quickly become one of my favorites. I look forward to reading more.

Aw, this was a very nice post. In thought I would like to put in writing like this additionally – taking time and precise effort to make an excellent article… however what can I say… I procrastinate alot and not at all seem to get something done.

I just wanted to drop by and say how much I enjoy your blog. Keep up the great work!

I like this weblog so much, saved to my bookmarks. “Respect for the fragility and importance of an individual life is still the mark of an educated man.” by Norman Cousins.

Thanks for expressing your ideas listed here. The other point is that each time a problem develops with a personal computer motherboard, people should not have some risk associated with repairing the item themselves because if it is not done right it can lead to irreparable damage to the complete laptop. It will always be safe just to approach any dealer of a laptop for any repair of its motherboard. They have technicians that have an competence in dealing with laptop computer motherboard difficulties and can carry out the right analysis and undertake repairs.

You really make it seem really easy together with your presentation but I to find this matter to be actually something which I think I would by no means understand. It sort of feels too complex and very wide for me. I’m taking a look forward for your subsequent post, I?¦ll try to get the hang of it!

I appreciate the time and effort you put into creating this content. It’s very informative.

Your writing style is engaging and easy to follow. I always enjoy reading your articles.

I am impressed with this internet site, real I am a big fan .

Hi there, You have done a great job. I will definitely digg it and personally recommend to my friends. I am sure they’ll be benefited from this web site.

Thanks for the new things you have uncovered in your short article. One thing I want to reply to is that FSBO connections are built eventually. By bringing out yourself to owners the first few days their FSBO can be announced, ahead of the masses start calling on Wednesday, you generate a good network. By giving them methods, educational materials, free records, and forms, you become a great ally. By subtracting a personal interest in them and also their circumstances, you build a solid relationship that, many times, pays off as soon as the owners decide to go with a realtor they know and trust — preferably you.

Thanks for sharing excellent informations. Your website is so cool. I’m impressed by the details that you’ve on this blog. It reveals how nicely you understand this subject. Bookmarked this web page, will come back for extra articles. You, my pal, ROCK! I found just the info I already searched all over the place and just could not come across. What a great site.

Hmm is anyone else having problems with the images on this blog loading? I’m trying to figure out if its a problem on my end or if it’s the blog. Any responses would be greatly appreciated.

I reckon something really special in this internet site.

Hey, you used to write magnificent, but the last several posts have been kinda boring?K I miss your tremendous writings. Past few posts are just a bit out of track! come on!

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It in fact was a amusement account it. Look advanced to more added agreeable from you! By the way, how could we communicate?

I do enjoy the way you have framed this concern and it really does give me personally some fodder for thought. Nonetheless, from everything that I have experienced, I basically trust as the actual opinions pack on that folks stay on issue and not get started on a tirade regarding the news du jour. Yet, thank you for this exceptional piece and even though I do not necessarily go along with the idea in totality, I regard the point of view.

I?¦m not sure where you’re getting your information, however good topic. I must spend a while studying more or understanding more. Thanks for excellent information I used to be searching for this info for my mission.

Are you even real? briansclub

I love your writing style really enjoying this web site.

What’s Going down i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I have discovered It absolutely useful and it has helped me out loads. I hope to contribute & help other users like its helped me. Great job.

It抯 really a great and useful piece of info. I am glad that you shared this helpful info with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

Very interesting topic, regards for putting up.

Keep working ,splendid job!

I got what you mean , appreciate it for posting.Woh I am pleased to find this website through google.

What¦s Going down i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I have found It positively useful and it has helped me out loads. I am hoping to give a contribution & assist other customers like its helped me. Great job.

Some really wonderful work on behalf of the owner of this site, perfectly outstanding subject matter.

Hello, you used to write excellent, but the last few posts have been kinda boring… I miss your great writings. Past several posts are just a little out of track! come on!

I’m typically to blogging and i actually admire your content. The article has actually peaks my interest. I’m going to bookmark your web site and keep checking for brand new information.

Hello, you used to write wonderful, but the last few posts have been kinda boringK I miss your great writings. Past few posts are just a little out of track! come on!

Very great post. I simply stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I have really loved browsing your blog posts. After all I抣l be subscribing to your feed and I’m hoping you write once more soon!

Thanks for the helpful posting. It is also my belief that mesothelioma cancer has an incredibly long latency phase, which means that signs and symptoms of the disease might not emerge right up until 30 to 50 years after the original exposure to asbestos fiber. Pleural mesothelioma, that’s the most common sort and influences the area across the lungs, may cause shortness of breath, chest muscles pains, as well as a persistent cough, which may cause coughing up blood vessels.

Good site! I truly love how it is easy on my eyes and the data are well written. I’m wondering how I might be notified whenever a new post has been made. I have subscribed to your RSS which must do the trick! Have a nice day!

Would love to always get updated outstanding web site! .

hello there and thank you on your information – I’ve definitely picked up anything new from right here. I did then again experience some technical issues using this website, since I skilled to reload the site many times previous to I may just get it to load properly. I had been brooding about if your web hosting is OK? No longer that I’m complaining, however slow loading cases times will sometimes impact your placement in google and could damage your high quality ranking if advertising and ***********|advertising|advertising|advertising and *********** with Adwords. Well I’m including this RSS to my email and can glance out for a lot more of your respective exciting content. Make sure you update this once more soon..

Great post, you have pointed out some good points, I also believe this s a very fantastic website.

I think this site holds very good indited subject matter articles.

Saved as a favorite, I really like your blog!

Its great as your other posts : D, thanks for putting up. “Say not, ‘I have found the truth,’ but rather, ‘I have found a truth.'” by Kahlil Gibran.

I think this is one of the most vital information for me. And i’m glad reading your article. But should remark on some general things, The website style is great, the articles is really great : D. Good job, cheers

I have noticed that over the course of building a relationship with real estate owners, you’ll be able to get them to understand that, in each and every real estate transaction, a payment is paid. Finally, FSBO sellers do not “save” the percentage. Rather, they struggle to win the commission through doing a agent’s job. In accomplishing this, they shell out their money in addition to time to conduct, as best they might, the responsibilities of an adviser. Those duties include revealing the home by means of marketing, introducing the home to buyers, creating a sense of buyer urgency in order to prompt an offer, organizing home inspections, managing qualification check ups with the mortgage lender, supervising fixes, and aiding the closing of the deal.

Hello There. I found your blog using msn. This is a very well written article. I will make sure to bookmark it and come back to read more of your useful information. Thanks for the post. I’ll definitely return.

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wished to mention that I’ve truly loved surfing around your blog posts. In any case I’ll be subscribing on your rss feed and I’m hoping you write once more soon!

Thank you for sharing with us, I believe this website genuinely stands out : D.

hey there and thank you for your info – I have definitely picked up anything new from right here. I did however expertise some technical issues using this site, since I experienced to reload the website lots of times previous to I could get it to load properly. I had been wondering if your hosting is OK? Not that I am complaining, but slow loading instances times will very frequently affect your placement in google and could damage your quality score if advertising and marketing with Adwords. Anyway I am adding this RSS to my email and can look out for much more of your respective intriguing content. Ensure that you update this again soon..

Thanks , I have just been looking for info about this subject for ages and yours is the best I have discovered till now. But, what about the bottom line? Are you sure about the source?

Thank you for another informative web site. Where else may just I am getting that type of information written in such an ideal method? I have a challenge that I’m simply now operating on, and I’ve been at the glance out for such info.

Real great information can be found on site. “I am not merry but I do beguile The thing I am, by seeming otherwise.” by William Shakespeare.

Perfect piece of work you have done, this internet site is really cool with good info .

It’s actually a nice and helpful piece of info. I am happy that you shared this helpful information with us. Please stay us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

Hi there, i read your blog occasionally and i own a similar one and i was just curious if you get a lot of spam feedback? If so how do you prevent it, any plugin or anything you can suggest? I get so much lately it’s driving me insane so any assistance is very much appreciated.

Some times its a pain in the ass to read what blog owners wrote but this website is real user pleasant! .

I have been checking out some of your posts and i can state clever stuff. I will definitely bookmark your blog.

I really enjoy examining on this web site, it contains fantastic blog posts. “Sometime they’ll give a war and nobody will come.” by Carl Sandburg.

I feel this is among the so much important info for me. And i am happy reading your article. But wanna commentary on some common issues, The site taste is perfect, the articles is actually nice : D. Good task, cheers

An added important aspect is that if you are a senior citizen, travel insurance regarding pensioners is something that is important to really look at. The older you are, the greater at risk you’re for having something negative happen to you while abroad. If you are certainly not covered by quite a few comprehensive insurance, you could have a number of serious complications. Thanks for revealing your advice on this weblog.

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wished to say that I have truly enjoyed surfing around your blog posts. After all I will be subscribing to your rss feed and I hope you write again soon!

You can certainly see your expertise in the work you write. The world hopes for even more passionate writers like you who aren’t afraid to say how they believe. Always follow your heart.

WONDERFUL Post.thanks for share..more wait .. …

As I website owner I think the subject matter here is rattling fantastic, appreciate it for your efforts.

I have been exploring for a bit for any high-quality articles or blog posts on this kind of area . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this site. Reading this info So i am happy to convey that I have a very good uncanny feeling I discovered exactly what I needed. I most certainly will make certain to don’t forget this website and give it a look regularly.

It is appropriate time to make some plans for the longer term and it’s time to be happy. I have read this submit and if I could I want to counsel you some attention-grabbing issues or advice. Perhaps you could write subsequent articles relating to this article. I wish to read more things about it!

It’s hard to find knowledgeable people on this topic, but you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

I抣l right away grab your rss as I can not find your email subscription link or e-newsletter service. Do you have any? Please let me know so that I could subscribe. Thanks.

Nice post. I study something tougher on completely different blogs everyday. It would all the time be stimulating to read content material from other writers and follow a bit of something from their store. I抎 prefer to make use of some with the content material on my weblog whether you don抰 mind. Natually I抣l offer you a link in your web blog. Thanks for sharing.

hey there and thank you on your info – I have certainly picked up something new from right here. I did then again experience some technical points using this web site, as I experienced to reload the web site many instances previous to I could get it to load correctly. I were brooding about if your web hosting is OK? Now not that I am complaining, however sluggish loading circumstances times will often affect your placement in google and could damage your high-quality score if ads and ***********|advertising|advertising|advertising and *********** with Adwords. Anyway I am including this RSS to my email and could glance out for much more of your respective intriguing content. Make sure you update this again very soon..

Thank you for sharing excellent informations. Your web-site is very cool. I’m impressed by the details that you’ve on this website. It reveals how nicely you perceive this subject. Bookmarked this website page, will come back for more articles. You, my pal, ROCK! I found simply the info I already searched all over the place and just could not come across. What a perfect site.

Hello. remarkable job. I did not anticipate this. This is a splendid story. Thanks!

Hello There. I discovered your weblog the usage of msn. That is a really smartly written article. I will make sure to bookmark it and come back to read more of your useful information. Thank you for the post. I will certainly return.

Woh I like your posts, saved to bookmarks! .

We stumbled over here by a different website and thought I might as well check things out. I like what I see so now i’m following you. Look forward to checking out your web page repeatedly.

hello!,I like your writing very much! share we communicate more about your article on AOL? I require a specialist on this area to solve my problem. May be that’s you! Looking forward to see you.

Some genuinely superb articles on this site, thanks for contribution.

Hi there would you mind sharing which blog platform you’re working with? I’m planning to start my own blog in the near future but I’m having a hard time making a decision between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal. The reason I ask is because your design and style seems different then most blogs and I’m looking for something completely unique. P.S My apologies for being off-topic but I had to ask!

With havin so much content and articles do you ever run into any issues of plagorism or copyright infringement? My site has a lot of exclusive content I’ve either created myself or outsourced but it looks like a lot of it is popping it up all over the internet without my agreement. Do you know any solutions to help protect against content from being stolen? I’d certainly appreciate it.

Sweet blog! I found it while browsing on Yahoo News. Do you have any suggestions on how to get listed in Yahoo News? I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get there! Cheers

As I web-site possessor I believe the content material here is rattling excellent , appreciate it for your hard work. You should keep it up forever! Best of luck.

The subsequent time I read a weblog, I hope that it doesnt disappoint me as much as this one. I mean, I know it was my option to read, however I actually thought youd have something fascinating to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about something that you could fix for those who werent too busy looking for attention.

I’m still learning from you, while I’m trying to reach my goals. I definitely liked reading everything that is written on your blog.Keep the information coming. I loved it!

I have been exploring for a bit for any high-quality articles or weblog posts in this sort of area . Exploring in Yahoo I finally stumbled upon this website. Studying this information So i¦m glad to show that I have a very excellent uncanny feeling I discovered exactly what I needed. I so much no doubt will make sure to do not forget this site and provides it a look regularly.

It’s hard to find knowledgeable people on this topic, but you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

Very good written story. It will be useful to anyone who utilizes it, including me. Keep doing what you are doing – for sure i will check out more posts.

Hey There. I found your blog using msn. This is an extremely well written article. I will be sure to bookmark it and return to read more of your useful information. Thanks for the post. I will definitely return.

Its great as your other blog posts : D, thanks for putting up.

very nice put up, i certainly love this website, keep on it

Hello. fantastic job. I did not anticipate this. This is a splendid story. Thanks!

Good – I should certainly pronounce, impressed with your website. I had no trouble navigating through all the tabs and related information ended up being truly easy to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it in the least. Reasonably unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or anything, site theme . a tones way for your client to communicate. Nice task..

Hi there just wanted to give you a brief heads up and let you know a few of the images aren’t loading correctly. I’m not sure why but I think its a linking issue. I’ve tried it in two different browsers and both show the same results.

Simply wanna remark on few general things, The website style and design is perfect, the articles is very wonderful : D.

I just could not depart your website before suggesting that I extremely enjoyed the standard info a person provide for your visitors? Is gonna be back often to check up on new posts

Regards for all your efforts that you have put in this. very interesting info .

Hey would you mind letting me know which web host you’re using? I’ve loaded your blog in 3 completely different internet browsers and I must say this blog loads a lot faster then most. Can you suggest a good web hosting provider at a fair price? Thank you, I appreciate it!

This is the right blog for anyone who wants to find out about this topic. You realize so much its almost hard to argue with you (not that I actually would want…HaHa). You definitely put a new spin on a topic thats been written about for years. Great stuff, just great!

Great blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere? A theme like yours with a few simple adjustements would really make my blog stand out. Please let me know where you got your theme. Bless you

I like your writing style truly enjoying this internet site.

We are a group of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our community. Your website offered us with valuable information to work on. You have done an impressive job and our entire community will be thankful to you.

Hey very cool site!! Guy .. Beautiful .. Amazing .. I’ll bookmark your blog and take the feeds also…I am happy to search out a lot of useful info here within the put up, we need work out more techniques in this regard, thank you for sharing.

Simply desire to say your article is as astounding. The clearness for your put up is just great and i could suppose you’re a professional on this subject. Fine with your permission allow me to grasp your feed to keep updated with forthcoming post. Thank you 1,000,000 and please carry on the rewarding work.

I real thankful to find this web site on bing, just what I was searching for : D too saved to favorites.

We’re a group of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our community. Your site offered us with valuable info to work on. You’ve done a formidable job and our whole community will be grateful to you.

This is exactly what I was looking for. Thanks for providing such valuable information.

I just couldn’t depart your website prior to suggesting that I actually enjoyed the standard information a person provide for your visitors? Is gonna be back often in order to check up on new posts

You are my inspiration , I have few blogs and often run out from to brand.

Thanks for every other informative web site. Where else may I get that kind of info written in such an ideal method? I have a project that I am simply now operating on, and I have been at the look out for such info.

Would you be eager about exchanging links?

What i don’t realize is actually how you are now not really much more neatly-liked than you may be right now. You’re very intelligent. You already know therefore significantly in relation to this subject, produced me in my opinion imagine it from a lot of various angles. Its like men and women don’t seem to be interested except it is something to do with Lady gaga! Your own stuffs outstanding. All the time handle it up!

Hi there! This post couldn’t be written any better! Reading through this post reminds me of my previous room mate! He always kept talking about this. I will forward this article to him. Pretty sure he will have a good read. Thank you for sharing!

Howdy, i read your blog from time to time and i own a similar one and i was just curious if you get a lot of spam remarks? If so how do you prevent it, any plugin or anything you can suggest? I get so much lately it’s driving me crazy so any help is very much appreciated.

Someone essentially help to make severely articles I would state. This is the very first time I frequented your website page and thus far? I surprised with the analysis you made to create this actual post extraordinary. Great process!

Very great post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wished to mention that I have really enjoyed surfing around your weblog posts. After all I will be subscribing for your rss feed and I am hoping you write again very soon!

Wonderful site. Plenty of helpful information here. I¦m sending it to a few pals ans additionally sharing in delicious. And obviously, thanks to your sweat!

“If you’re looking for a digital agency in , Briansclub I highly recommend [Company Name]

I view something really special in this web site.

Best view i have ever seen !

This web site is really a walk-through for all of the info you wanted about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse here, and you’ll definitely discover it.

I like this website its a master peace ! Glad I discovered this on google .

Almost all of the things you say is supprisingly precise and that makes me wonder the reason why I had not looked at this in this light before. This particular article really did switch the light on for me personally as far as this topic goes. But there is one issue I am not necessarily too comfy with and whilst I attempt to reconcile that with the core theme of your position, let me observe exactly what the rest of the readers have to say.Very well done.

Thanks again for the blog.

fantastic points altogether, you simply gained a new reader. What would you recommend about your post that you made a few days ago? Any positive?

F*ckin’ amazing things here. I am very satisfied to look your post. Thank you so much and i am having a look forward to touch you. Will you please drop me a e-mail?

I conceive you have remarked some very interesting details , thankyou for the post.

I am no longer positive the place you are getting your info, but good topic. I must spend a while finding out much more or working out more. Thank you for magnificent info I used to be searching for this information for my mission.

My brother recommended I may like this blog. He was totally right. This submit actually made my day. You can not believe just how much time I had spent for this information! Thank you!

Howdy very nice site!! Guy .. Excellent .. Superb .. I’ll bookmark your website and take the feeds additionally…I am glad to find numerous useful information right here within the publish, we want develop more techniques in this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

This is a very good tips especially to those new to blogosphere, brief and accurate information… Thanks for sharing this one. A must read article.

Write more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seems as though you relied on the video to make your point. You obviously know what youre talking about, why throw away your intelligence on just posting videos to your site when you could be giving us something informative to read?

Whenever I go on my computer after a few minutes (I’d say about 5) it just restarts for some reason. I’ve tried to restore my computer but can’t because it will restart before it finishes. How can i stop the restarting or reatore my computer when this is happening Someone please help.

Whats Happening i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve found It positively helpful and it has aided me out loads. I am hoping to contribute & aid other customers like its aided me. Great job.

Enjoyed studying this, very good stuff, thanks.

Hiya! Quick question that’s entirely off topic. Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly? My weblog looks weird when browsing from my iphone4. I’m trying to find a template or plugin that might be able to fix this problem. If you have any suggestions, please share. Appreciate it!

It is in reality a great and helpful piece of info. I am happy that you shared this helpful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

Do you mind if I quote a few of your articles as long as I provide credit and sources back to your blog? My website is in the very same niche as yours and my visitors would certainly benefit from a lot of the information you provide here. Please let me know if this okay with you. Regards!

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!

Hi, Neat post. There is a problem with your website in internet explorer, would check this… IE still is the market leader and a good portion of people will miss your great writing due to this problem.

It is the best time to make a few plans for the longer term and it’s time to be happy. I’ve learn this submit and if I may I want to counsel you some interesting issues or tips. Maybe you could write next articles relating to this article. I desire to learn more issues approximately it!

I do not even know the way I ended up here, however I assumed this put up used to be good. I do not know who you’re but definitely you are going to a famous blogger should you are not already 😉 Cheers!

Hi my friend! I wish to say that this article is awesome, nice written and include approximately all significant infos. I would like to see more posts like this.

Hello. remarkable job. I did not expect this. This is a impressive story. Thanks!

As soon as I observed this site I went on reddit to share some of the love with them.

F*ckin’ remarkable things here. I am very glad to see your post. Thanks a lot and i am looking forward to contact you. Will you please drop me a e-mail?

Good web site! I really love how it is easy on my eyes and the data are well written. I am wondering how I could be notified whenever a new post has been made. I have subscribed to your RSS feed which must do the trick! Have a nice day!

I always was interested in this subject and still am, appreciate it for putting up.

Hello there, I discovered your blog by means of Google while looking for a comparable subject, your site came up, it appears to be like great. I’ve bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

Would you be all for exchanging links?

I like what you guys tend to be up too. This kind of clever work and exposure! Keep up the fantastic works guys I’ve included you guys to our blogroll.

I will immediately snatch your rss as I can not find your email subscription link or e-newsletter service. Do you have any? Kindly allow me recognise in order that I could subscribe. Thanks.

Virtually all of the things you say is supprisingly appropriate and it makes me wonder why I had not looked at this with this light previously. This particular piece truly did turn the light on for me as far as this particular subject goes. However at this time there is actually one particular position I am not really too comfy with and whilst I make an effort to reconcile that with the actual central idea of your point, permit me see just what the rest of your readers have to point out.Nicely done.

I precisely wanted to thank you so much again. I am not sure the things that I could possibly have taken care of without the actual aspects revealed by you over that area of interest. It seemed to be a real troublesome issue in my position, however , considering the professional form you dealt with that forced me to cry with gladness. I am happy for your work and then sincerely hope you really know what an amazing job you have been doing instructing people today using your web blog. Most probably you’ve never encountered all of us.

I conceive you have observed some very interesting details , appreciate it for the post.

hi!,I like your writing very much! share we communicate more about your article on AOL? I require an expert on this area to solve my problem. Maybe that’s you! Looking forward to see you.

Well I truly enjoyed studying it. This information provided by you is very effective for proper planning.

Hello There. I discovered your blog the use of msn. That is a really well written article. I will be sure to bookmark it and return to learn extra of your helpful info. Thank you for the post. I will certainly comeback.

I was just searching for this info for some time. After six hours of continuous Googleing, at last I got it in your site. I wonder what’s the lack of Google strategy that do not rank this kind of informative web sites in top of the list. Usually the top websites are full of garbage.

I have read some good stuff here. Certainly worth bookmarking for revisiting. I surprise how much effort you put to create such a great informative website.

very good post, i definitely love this website, keep on it

Nice weblog here! Also your site a lot up fast! What host are you the usage of? Can I get your associate link for your host? I desire my website loaded up as fast as yours lol

I always was interested in this subject and still am, appreciate it for putting up.

hi!,I love your writing very much! share we keep in touch more approximately your article on AOL? I need an expert on this area to solve my problem. Maybe that is you! Looking ahead to look you.

I discovered your weblog web site on google and verify just a few of your early posts. Continue to keep up the superb operate. I simply further up your RSS feed to my MSN News Reader. Seeking forward to reading extra from you later on!…

Nice post. I was checking constantly this blog and I am impressed! Very useful info particularly the last part 🙂 I care for such info much. I was looking for this certain information for a long time. Thank you and good luck.

Heya! I’m at work browsing your blog from my new iphone! Just wanted to say I love reading your blog and look forward to all your posts! Keep up the great work!

8 regions of phi delta chi

What¦s Happening i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I have discovered It absolutely useful and it has aided me out loads. I am hoping to give a contribution & assist other users like its helped me. Good job.

I just couldn’t go away your site prior to suggesting that I actually enjoyed the standard info an individual provide in your visitors? Is going to be back ceaselessly to check out new posts

Thanks for all your efforts that you have put in this. very interesting information.

Wow! Thank you! I continuously wanted to write on my site something like that. Can I implement a fragment of your post to my blog?

Im not sure the place you’re getting your info, but good topic. I must spend a while finding out much more or figuring out more. Thank you for fantastic information I used to be looking for this info for my mission.

Hello. excellent job. I did not anticipate this. This is a fantastic story. Thanks!

I conceive this web site holds some very fantastic information for everyone : D.

Usually I don’t read article on blogs, but I would like to say that this write-up very forced me to try and do so! Your writing style has been surprised me. Thanks, quite nice article.

Regards for this marvellous post, I am glad I noticed this site on yahoo.

You could certainly see your enthusiasm within the work you write. The world hopes for more passionate writers like you who are not afraid to mention how they believe. Always go after your heart. “The point of quotations is that one can use another’s words to be insulting.” by Amanda Cross.

It’s onerous to seek out educated individuals on this topic, however you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

I’d have to examine with you here. Which is not one thing I usually do! I take pleasure in reading a post that may make folks think. Additionally, thanks for permitting me to comment!

I precisely needed to thank you so much once again. I’m not certain the things that I would’ve achieved in the absence of the type of basics shared by you concerning such a area. It had been a challenging scenario in my circumstances, nevertheless being able to see a new specialized way you resolved it took me to jump for happiness. Extremely grateful for your assistance and thus sincerely hope you comprehend what a great job you were carrying out teaching most people all through your website. More than likely you’ve never met all of us.

I think other site proprietors should take this web site as an model, very clean and fantastic user genial style and design, as well as the content. You’re an expert in this topic!

I got what you mean , thankyou for putting up.Woh I am glad to find this website through google.

When I originally commented I clicked the “Notify me when new comments are added” checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get four emails with the same comment. Is there any way you can remove me from that service? Cheers!

Thank you for sharing with us, I think this website really stands out : D.

Well I definitely enjoyed studying it. This information offered by you is very constructive for proper planning.

Hello, you used to write great, but the last several posts have been kinda boring… I miss your super writings. Past few posts are just a little out of track! come on!

As a Newbie, I am constantly browsing online for articles that can be of assistance to me. Thank you