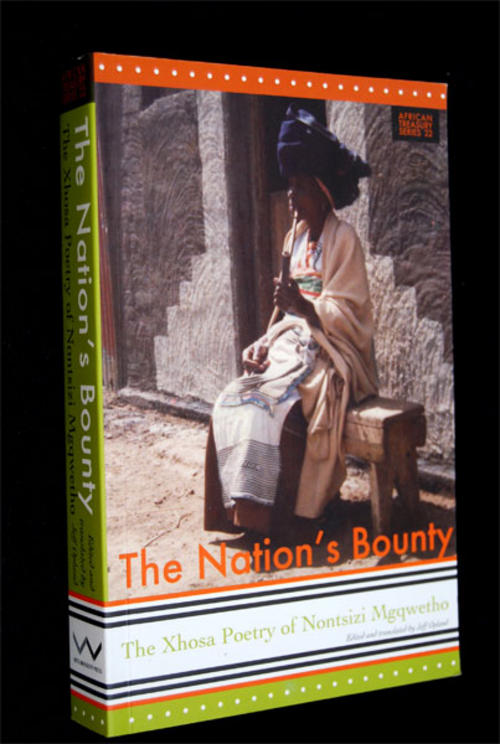

The Nation’s Bounty – The Xhosa Poetry of Nontsizi Mgqwetho edited by Jeff Opland

Thapelo Mokoatsi

Nontsizi Mgqwetho was a renegade and in many ways far ahead of her time. As a poet, Imbongi (praise singer) and political commentator Mgqwetho shattered all the moulds confining black women in South Africa in the 1920s.

We consider the praise singers or Imbongi to be the precursors of our modern journalists. Historically the Imbongi was respected and given the task of both praising and criticising the chief and other leaders. Mgqwetho spoke out fearlessly and her lyrical verse was also published in local newspapers.

In a profile prepared for South African History Online, academic, Jeff Opland writes that Mgqwetho had published 97 poems and three articles for the Johannesburg based newspaper, Umteteli wa Bantu, between 1920 and 1929. Opland describes Mgwetho as the first and only female poet to produce a significant body of work in Xhosa.

According to Opland, Mgqwetho first published her poetry in 1920 with the Johannesburg based weekly newspaper, Umteteleli wa Bantu (Mouthpiece of the People). During the 1920s – after the passing of the Native (Black) Affairs Act, and many other similar laws – there were dynamic debates about the future of South Africa, the need for unity in the face of racial oppression and the fragmentation of black people.

The significance of a black female voice — adding substance to these debates during that era — cannot be understated. In a piece published in Poetry International Rotterdam Isabel Hofmeyr, professor of Literature at Wits University, notes that while these debates were often dominated by males – especially those active in political formations, like the Congress movement, and professionals – Mgqwetho played a decisive role in opening up issues. This was at a time when many female voices were stifled by not having access to education and society’s strong gender bias.

Amplifying Her Voice

Hofmeyr notes that by using isiXhosa imaginatively, Mgqwetho was able to not only convey her views but also to amplify her voice.

Looking at the life and creative work of this remarkable woman I was reminded of these words by Pumla Gqola in her book, A Renegade Called Simphiwe:

“There is an idealized model of (Black) femininity in post-apartheid South Africa. On the surface, she embodies the transformational promise of a new South Africa: a radical departure from apartheid stereotypes, she is an articulate, independent, ambitious woman with increasing control over her public and financial life.”

Although Gqola refers to Simphiwe Dana here, it is my opinion the latter part of this description could easily have applied to Nontsizi Mgqwetho.

While her work speaks volumes, very little is known of the Mgqwetho’s personal life. Jeff Opland, who is also the editor of the book The Nation’s Bounty: The Xhosa Poetry of Nontsizi Mgqwetho (2007), tries to uncover the mysteries of Mgqwetho’s life by following the footprints she leaves in her poetry.

In the South African History Online profile, he writes:

“In a poem published on 2 December 1922, lamenting the death of her mother, she gives her mother’s name as Emmah Jane Mgqwetho, the daughter of Zingelwa of the Cwerha clan, and associates her with the Hewu district near Queenstown.

Although Xhosa personal praises often employ hyperbole and caricature, some information about Mgqwetho can be gleaned from a poem about herself published in Umteleli on 12 January 1924. She seems to have been arrested, probably for political activity, if we may take literally the lines:

‘What a fool I was sucking up to the whites! / Next thing I knew the cops had the cuffs on me.’ She describes herself as physically unappealing, a bulky woman with ‘matchstick legs’, and may possibly have been unmarried,”

In a classical 1920s polemic, Mgqwetho displays her critical stance when she takes issue with L T Mvabaza, editor of the ANC-founded newspaper Abantu Bantu. Mvabaza accused Umteteli wa Bantu, the paper that published Mgqwetho’s work, of dividing the African people. Mgqwetho responds with this poem published in Umteteli wa Bantu in1920:

Mvabaza, I have long had my eye on you.

Umteteli wa Bantu long saw through you.

You are a sack without water, left to breed tadpoles.

Mvabaza, you are a shifty opportunist carried along on a plate.

When you arrived in Johannesburg, you suddenly became a leader. We have made a bad start.

We seek a ford to cross over.

We are suffering high casualties because of reckless rabble-rousers. Aha! I told you! Agent provocateurs of Jeppe

Who command us to charge

While they stay in the trench.

Africa is perishing because of reckless leaders.

In a piece published on the website for Poetry International Rotterdam, Opland describes Nontsizi as an anguished voice of an urban woman, “confronting male dominance, ineffective leadership, black apathy, white malice and indifference, economic exploitation and a tragic history of nineteenth century territorial and cultural dispossession.”

In the same piece Opland describes how Mgqwetho defied the traditional typecast of the rural male Imbongi by appropriating the role. Opland observes that as a woman Mgqwetho would not have been allowed to do public performances for a Chief. According to Opland, Mgqwetho overcame this limitation by using the newspaper as a platform. Opland writes:

“The newspaper licensed her poetry and afforded her access to a public that tradition denied her. She was free to appropriate the voice of an imbongi, and claimed the imbongi’s right to criticise leaders. Like an imbongi, she drew attention to social ills, and sought to shape attitudes and mobilise action”.

Attractive component of content. I simply stumbled upon your website and in accession capital to claim that I acquire in fact enjoyed account your weblog posts. Anyway I抣l be subscribing to your feeds and even I achievement you get admission to persistently rapidly.

Wow! This could be one particular of the most beneficial blogs We’ve ever arrive across on this subject. Actually Excellent. I am also an expert in this topic so I can understand your hard work.

Heya i am for the first time here. I came across this board and I find It really useful & it helped me out a lot. I hope to give something back and aid others like you aided me.

You made some clear points there. I looked on the internet for the issue and found most individuals will agree with your site.

This really answered my problem, thank you!

Nice post. I learn something more difficult on different blogs everyday. It should all the time be stimulating to learn content from other writers and observe slightly one thing from their store. I’d want to use some with the content material on my weblog whether you don’t mind. Natually I’ll offer you a hyperlink in your web blog. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks for another informative website. Where else could I get that kind of information written in such an ideal way? I have a project that I’m just now working on, and I have been on the look out for such information.

Thank you for sharing superb informations. Your web-site is very cool. I’m impressed by the details that you’ve on this web site. It reveals how nicely you perceive this subject. Bookmarked this web page, will come back for extra articles. You, my friend, ROCK! I found just the information I already searched all over the place and just couldn’t come across. What an ideal website.

Thanks a lot for giving everyone an extremely breathtaking opportunity to read in detail from this site. It’s always so kind plus jam-packed with a good time for me and my office friends to visit your blog on the least thrice in one week to see the fresh tips you have got. And definitely, I’m actually amazed with your amazing information you serve. Some 1 areas in this posting are without a doubt the most suitable we’ve had.

I have fun with, cause I found exactly what I was looking for. You’ve ended my 4 day lengthy hunt! God Bless you man. Have a nice day. Bye

Hey very cool site!! Man .. Beautiful .. Amazing .. I’ll bookmark your web site and take the feeds also…I am happy to find numerous useful information here in the post, we need work out more techniques in this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

I got good info from your blog

Hmm is anyone else encountering problems with the images on this blog loading? I’m trying to determine if its a problem on my end or if it’s the blog. Any responses would be greatly appreciated.

Wow! This could be one particular of the most helpful blogs We have ever arrive across on this subject. Basically Fantastic. I am also a specialist in this topic so I can understand your hard work.

Incredible! This blog looks exactly like my old one! It’s on a entirely different subject but it has pretty much the same page layout and design. Wonderful choice of colors!

You have remarked very interesting points! ps decent internet site. “I just wish we knew a little less about his urethra and a little more about his arms sales to Iran.” by Andrew A. Rooney.

Very interesting subject, thankyou for putting up. “He who seizes the right moment is the right man.” by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

You are a very bright person!

404 DICK NOT FOUND: Tub Girl

You are my inspiration , I possess few web logs and sometimes run out from to post : (.

But wanna remark on few general things, The website design is perfect, the subject matter is really wonderful. “Good judgment comes from experience, and experience comes from bad judgment.” by Barry LePatner.

You really make it seem so easy with your presentation but I find this topic to be actually something which I think I would never understand. It seems too complicated and extremely broad for me. I’m looking forward for your next post, I’ll try to get the hang of it!

Very interesting info!Perfect just what I was looking for!

Wonderful beat ! I wish to apprentice while you amend your web site, how could i subscribe for a blog web site? The account helped me a acceptable deal. I had been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast provided bright clear concept

Cum on my mouth: Twat

Cum inside my ass: Voyeur

See more porn: Blumpkin

I wish to express appreciation to this writer for bailing me out of such a problem. Right after searching throughout the the net and coming across things which are not productive, I believed my entire life was gone. Existing without the answers to the problems you have sorted out all through this blog post is a serious case, and the kind which might have adversely damaged my career if I had not come across your blog. Your own capability and kindness in touching all the details was helpful. I am not sure what I would have done if I hadn’t encountered such a thing like this. I am able to at this moment look forward to my future. Thanks a lot so much for the specialized and amazing help. I won’t be reluctant to endorse your web site to anybody who desires assistance about this topic.

I genuinely enjoy studying on this internet site, it has got superb blog posts.

Good ?V I should definitely pronounce, impressed with your site. I had no trouble navigating through all the tabs as well as related information ended up being truly easy to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it in the least. Quite unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or anything, website theme . a tones way for your client to communicate. Nice task..

I have been browsing online more than 3 hours nowadays, yet I by no means found any attention-grabbing article like yours. It’s pretty value enough for me. Personally, if all website owners and bloggers made good content material as you probably did, the internet might be a lot more helpful than ever before. “Wherever they burn books, they will also, in the end, burn people.” by Heinrich Heine.

F*ckin’ awesome things here. I am very glad to see your article. Thanks a lot and i am looking forward to contact you. Will you please drop me a e-mail?

Valuable information. Lucky me I found your website by accident, and I am shocked why this accident did not happened earlier! I bookmarked it.

Simply desire to say your article is as astounding. The clearness in your publish is just nice and that i can suppose you are knowledgeable on this subject. Fine along with your permission let me to grasp your RSS feed to keep up to date with drawing close post. Thank you one million and please carry on the enjoyable work.

I just couldn’t depart your site before suggesting that I extremely enjoyed the standard information a person provide for your visitors? Is going to be back often to check up on new posts

I am always looking online for tips that can help me. Thanks!

Pretty nice post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and wanted to say that I’ve truly enjoyed surfing around your blog posts. In any case I will be subscribing to your rss feed and I hope you write again soon!

But a smiling visitor here to share the love (:, btw outstanding design and style. “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not one bit simpler.” by Albert Einstein.

Pretty section of content. I simply stumbled upon your weblog and in accession capital to claim that I acquire in fact enjoyed account your weblog posts. Any way I’ll be subscribing to your feeds and even I fulfillment you get entry to consistently rapidly.

You really make it seem so easy with your presentation but I find this topic to be actually something which I think I would never understand. It seems too complex and very broad for me. I am looking forward for your next post, I will try to get the hang of it!

An interesting discussion is worth comment. I think that it’s best to write more on this matter, it may not be a taboo topic but typically individuals are not sufficient to talk on such topics. To the next. Cheers

Hey there, You have done a fantastic job. I’ll definitely digg it and in my opinion suggest to my friends. I am sure they will be benefited from this website.

Wonderful work! This is the type of info that are supposed to be shared across the net. Shame on Google for no longer positioning this submit higher! Come on over and seek advice from my site . Thank you =)

Wohh exactly what I was looking for, thanks for posting.

Hello there, You’ve done a fantastic job. I’ll certainly digg it and in my opinion recommend to my friends. I am confident they will be benefited from this web site.

Nice post. I was checking continuously this weblog and I’m impressed! Extremely helpful info specifically the ultimate phase 🙂 I handle such info a lot. I used to be looking for this particular information for a long time. Thanks and best of luck.

I have been reading out some of your posts and i must say nice stuff. I will definitely bookmark your site.

I have been exploring for a little bit for any high quality articles or blog posts in this sort of space . Exploring in Yahoo I finally stumbled upon this site. Reading this information So i am happy to exhibit that I have a very good uncanny feeling I came upon exactly what I needed. I such a lot definitely will make certain to don’t fail to remember this website and provides it a glance regularly.

Hello there, You have done an excellent job. I will definitely digg it and personally recommend to my friends. I’m sure they will be benefited from this website.

Nice post. I was checking constantly this blog and I am impressed! Very useful info particularly the last part 🙂 I care for such info a lot. I was looking for this certain information for a very long time. Thank you and best of luck.

I am forever thought about this, appreciate it for putting up.

I have not checked in here for some time as I thought it was getting boring, but the last several posts are great quality so I guess I will add you back to my everyday bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

Just what I was looking for, appreciate it for posting.

I think this is among the most vital info for me. And i’m happy reading your article. But wanna observation on few normal things, The web site taste is great, the articles is really nice : D. Just right process, cheers

I am really impressed along with your writing abilities and also with the format on your blog. Is that this a paid topic or did you modify it yourself? Either way keep up the nice quality writing, it is uncommon to see a nice weblog like this one today..

You actually make it appear really easy along with your presentation but I find this topic to be really something which I feel I might never understand. It sort of feels too complicated and very extensive for me. I am taking a look forward to your subsequent publish, I will try to get the grasp of it!

Thank you for sharing your unique perspective on things through your blog.

Thank you for sharing δωρεαν παιχνιδια στο κινητοyour valuable insights with us.

I like this blog very much, Its a real nice situation to read and receive info . “Never hold discussions with the monkey when the organ grinder is in the room.” by Sir Winston Churchill.

Your blog has been suchδωρεαν παιχνιδια στο κινητοa helpful resource, thank you.

Your blog has helped me to learn new things and expand my horizons, thank you.

Terrific paintings! That is the kind of information that should be shared around the web. Shame on the seek engines for now not positioning this post higher! Come on over and visit my site . Thanks =)

Your blog has been a great resource for me to turn to, thank you.

I’d have to examine with you here. Which is not one thing I usually do! I take pleasure in reading a post that may make folks think. Additionally, thanks for permitting me to comment!

Hi there! Someone in my Facebook group shared this website with us so I came to give it a look. I’m definitely enjoying the information. I’m bookmarking and will be tweeting this to my followers! Great blog and fantastic style and design.

I’ve been absent for some time, but now I remember why I used to love this website. Thanks, I’ll try and check back more frequently. How frequently you update your web site?

Hi there! I know this is somewhat off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could get a captcha plugin for my comment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having trouble finding one? Thanks a lot!

I just wanted to drop by and say how much I enjoy your blog. Keep up the great work!

Your writing style is engaging and easy to follow. I always enjoy reading your articles.

Your blog is a fantastic resource for [insert topic]. Keep up the good work!

I just wanted to drop by and say how much I enjoy your blog. Keep up the great work!

Thanks for the informative content, it’s been really helpful!

You are my aspiration, I possess few blogs and very sporadically run out from to brand.

It’s appropriate time to make some plans for the future and it’s time to be happy. I have read this post and if I could I want to suggest you some interesting things or suggestions. Perhaps you could write next articles referring to this article. I wish to read more things about it!

I have learn several good stuff here. Certainly price bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how so much effort you place to make such a great informative web site.

Hi , I do believe this is an excellent blog. I stumbled upon it on Yahoo , i will come back once again. Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and help other people.

Hi , I do believe this is an excellent blog. I stumbled upon it on Yahoo , i will come back once again. Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and help other people.

Your writing style is engaging and easy to follow. I always enjoy reading your articles.

This post gave me a new perspective on [insert topic]. Thanks for broadening my horizons.

I learned so much from this post. Thank you for sharing your knowledge with us.

Thanks for sharing your expertise with us. Your insights are always helpful.

Hi there, I found your blog via Google while looking for a related topic, your website came up, it looks great. I have bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

F*ckin’ awesome things here. I’m very glad to see your article. Thanks a lot and i’m looking forward to contact you. Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?

I learned so much from this post. Thank you for sharing your knowledge with us.

Wow, wonderful weblog layout! How lengthy have you been running a blog for? you made blogging look easy. The total glance of your website is magnificent, let alone the content!

You have noted very interesting details ! ps nice internet site.

This post gave me a new perspective on [insert topic]. Thanks for broadening my horizons.

You can definitely see your enthusiasm within the work you write. The sector hopes for even more passionate writers like you who are not afraid to say how they believe. All the time go after your heart.

Great write-up, I’m regular visitor of one’s site, maintain up the nice operate, and It is going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.

Your blog has quickly become one of my favorites. I look forward to reading more.

I learned so much from this post. Thank you for sharing your knowledge with us.

You are my intake, I possess few web logs and infrequently run out from to brand.

Dead composed subject matter, thanks for entropy.

Hiya, I’m really glad I have found this info. Today bloggers publish only about gossips and internet and this is actually frustrating. A good site with exciting content, that is what I need. Thank you for keeping this web site, I will be visiting it. Do you do newsletters? Can not find it.

I will right away seize your rss as I can’t to find your email subscription link or newsletter service. Do you have any? Please permit me realize so that I could subscribe. Thanks.

You could definitely see your expertise within the work you write. The arena hopes for even more passionate writers like you who aren’t afraid to say how they believe. All the time follow your heart.

Really fantastic info can be found on web site. “The greatest mistake is trying to be more agreeable than you can be.” by Walter Bagehot.

Thank you for sharing superb informations. Your website is so cool. I am impressed by the details that you have on this website. It reveals how nicely you perceive this subject. Bookmarked this web page, will come back for extra articles. You, my pal, ROCK! I found just the info I already searched everywhere and just could not come across. What a great website.

Today, I went to the beachfront with my kids. I found a sea shell and gave it to my 4 year old daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She placed the shell to her ear and screamed. There was a hermit crab inside and it pinched her ear. She never wants to go back! LoL I know this is entirely off topic but I had to tell someone!

Hi, Neat post. There is an issue together with your site in internet explorer, could check this?K IE still is the market leader and a huge element of other people will pass over your wonderful writing due to this problem.

I was wondering if you ever considered changing the page layout of your blog? Its very well written; I love what youve got to say. But maybe you could a little more in the way of content so people could connect with it better. Youve got an awful lot of text for only having 1 or two pictures. Maybe you could space it out better?

It’s best to take part in a contest for among the best blogs on the web. I’ll recommend this web site!

Loving the information on this internet site, you have done outstanding job on the articles.

This really answered my downside, thanks!

I am now not certain the place you’re getting your information, however good topic. I needs to spend some time studying much more or figuring out more. Thank you for magnificent info I was on the lookout for this information for my mission.

Simply desire to say your article is as astounding. The clarity in your post is simply great and i can assume you are an expert on this subject. Fine with your permission allow me to grab your feed to keep updated with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please keep up the rewarding work.

Good write-up, I am regular visitor of one?¦s website, maintain up the nice operate, and It is going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.

Nice post. I was checking continuously this blog and I am impressed! Extremely helpful information particularly the last part 🙂 I care for such information a lot. I was looking for this certain info for a long time. Thank you and best of luck.

I like the efforts you have put in this, thankyou for all the great posts.

I loved as much as you will receive carried out right here. The sketch is attractive, your authored subject matter stylish. nonetheless, you command get got an edginess over that you wish be delivering the following. unwell unquestionably come more formerly again since exactly the same nearly very often inside case you shield this hike.

Way cool, some valid points! I appreciate you making this article available, the rest of the site is also high quality. Have a fun.

Hello there I am so thrilled I found your webpage, I really found you by accident, while I was looking on Digg for something else, Anyhow I am here now and would just like to say thanks for a fantastic post and a all round exciting blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to browse it all at the minute but I have book-marked it and also included your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read more, Please do keep up the excellent work.

I don’t unremarkably comment but I gotta state thanks for the post on this one : D.

Do you have a spam issue on this website; I also am a blogger, and I was wanting to know your situation; many of us have developed some nice procedures and we are looking to swap techniques with other folks, please shoot me an e-mail if interested.

You are my breathing in, I possess few web logs and rarely run out from brand :). “Follow your inclinations with due regard to the policeman round the corner.” by W. Somerset Maugham.

Very interesting points you have observed, thanks for putting up. “Curiosity is the key to creativity.” by Akio Morita.

Usually I don’t read article on blogs, but I would like to say that this write-up very forced me to try and do so! Your writing style has been amazed me. Thanks, quite nice article.

It?¦s really a cool and helpful piece of information. I am glad that you shared this useful information with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

Having read this I thought it was very informative. I appreciate you taking the time and effort to put this article together. I once again find myself spending way to much time both reading and commenting. But so what, it was still worth it!

Hmm it seems like your site ate my first comment (it was extremely long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I submitted and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I as well am an aspiring blog writer but I’m still new to everything. Do you have any tips for novice blog writers? I’d certainly appreciate it.

I got what you intend,saved to my bookmarks, very nice site.

Wow, fantastic blog structure! How lengthy have you been running a blog for? you make running a blog glance easy. The entire glance of your web site is magnificent, as smartly as the content material!

I’m still learning from you, but I’m trying to reach my goals. I absolutely liked reading everything that is written on your site.Keep the stories coming. I loved it!

Very interesting information!Perfect just what I was searching for! “The medium is the message.” by Marshall McLuhan.

I think this site contains very excellent pent subject matter posts.

You made certain good points there. I did a search on the matter and found mainly people will have the same opinion with your blog.

Lovely blog! I am loving it!! Will be back later to read some more. I am taking your feeds also

Heya i’m for the first time here. I came across this board and I find It really useful & it helped me out a lot. I hope to give something back and help others like you helped me.

I went over this site and I conceive you have a lot of wonderful information, saved to my bookmarks (:.

Excellent website. Lots of useful information here. I’m sending it to several pals ans additionally sharing in delicious. And of course, thank you for your effort!

Amazing! This blog looks just like my old one! It’s on a completely different subject but it has pretty much the same page layout and design. Outstanding choice of colors!

The next time I read a blog, I hope that it doesnt disappoint me as much as this one. I mean, I know it was my choice to read, but I actually thought youd have something interesting to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about something that you could fix if you werent too busy looking for attention.

Yay google is my world beater helped me to find this great site! .

I got what you intend, regards for posting.Woh I am glad to find this website through google.

I really appreciate this post. I have been looking all over for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You have made my day! Thx again!

I used to be very pleased to search out this internet-site.I wished to thanks to your time for this glorious learn!! I definitely enjoying every little bit of it and I have you bookmarked to take a look at new stuff you blog post.

Of course, what a splendid blog and illuminating posts, I will bookmark your website.Have an awsome day!

Your writing style is engaging and easy to follow. I always enjoy reading your articles.

Appreciate it for this post, I am a big big fan of this internet site would like to go on updated.

Great goods from you, man. I have understand your stuff previous to and you’re just too fantastic. I actually like what you have acquired here, really like what you’re saying and the way in which you say it. You make it enjoyable and you still take care of to keep it wise. I cant wait to read far more from you. This is actually a great site.

Hmm it looks like your site ate my first comment (it was super long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I wrote and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I as well am an aspiring blog writer but I’m still new to the whole thing. Do you have any tips and hints for first-time blog writers? I’d definitely appreciate it.

Hi my loved one! I want to say that this article is amazing, great written and come with almost all vital infos. I’d like to peer more posts like this.

I have been absent for a while, but now I remember why I used to love this web site. Thanks , I will try and check back more often. How frequently you update your website?

This web site is really a walk-through for all of the info you wanted about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse here, and you’ll definitely discover it.

Wow! Thank you! I constantly wanted to write on my blog something like that. Can I take a portion of your post to my blog?

I really lucky to find this website on bing, just what I was looking for : D besides bookmarked.

An impressive share, I just given this onto a colleague who was doing a little analysis on this. And he in fact bought me breakfast because I found it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the treat! But yeah Thnkx for spending the time to discuss this, I feel strongly about it and love reading more on this topic. If possible, as you become expertise, would you mind updating your blog with more details? It is highly helpful for me. Big thumb up for this blog post!

This is really attention-grabbing, You’re a very skilled blogger. I’ve joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your excellent post. Also, I’ve shared your website in my social networks!

What i don’t understood is actually how you’re not actually much more well-liked than you might be now. You’re very intelligent. You realize therefore considerably relating to this subject, produced me personally consider it from numerous varied angles. Its like men and women aren’t fascinated unless it’s one thing to do with Lady gaga! Your own stuffs great. Always maintain it up!

I discovered your blog site on google and check a few of your early posts. Continue to keep up the very good operate. I just additional up your RSS feed to my MSN News Reader. Seeking forward to reading more from you later on!…

Hiya, I’m really glad I’ve found this information. Today bloggers publish only about gossips and internet and this is really irritating. A good blog with exciting content, that’s what I need. Thank you for keeping this web site, I’ll be visiting it. Do you do newsletters? Cant find it.

But a smiling visitor here to share the love (:, btw outstanding pattern. “The price one pays for pursuing a profession, or calling, is an intimate knowledge of its ugly side.” by James Arthur Baldwin.

I’m really enjoying the theme/design of your web site. Do you ever run into any browser compatibility issues? A number of my blog audience have complained about my blog not operating correctly in Explorer but looks great in Firefox. Do you have any tips to help fix this problem?

Its excellent as your other articles : D, thanks for posting.

Thank you for sharing superb informations. Your site is very cool. I’m impressed by the details that you have on this website. It reveals how nicely you perceive this subject. Bookmarked this website page, will come back for more articles. You, my friend, ROCK! I found simply the information I already searched all over the place and simply couldn’t come across. What an ideal site.

I have been exploring for a bit for any high quality articles or weblog posts in this sort of space . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this website. Studying this info So i¦m satisfied to exhibit that I have a very just right uncanny feeling I came upon exactly what I needed. I most surely will make certain to don¦t forget this website and give it a glance regularly.

It’s hard to find knowledgeable people on this topic, but you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

I got what you intend,saved to my bookmarks, very decent website .

Wonderful beat ! I wish to apprentice whilst you amend your website, how can i subscribe for a blog web site? The account aided me a acceptable deal. I have been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast provided vivid clear concept

Fantastic article post.Much thanks again. Cool.

I was suggested this blog by my cousin. I’m not sure whether this post is written by him as nobody else know such detailed about my problem. You are wonderful! Thanks!

My husband and i have been quite joyful Albert managed to deal with his basic research from the ideas he was given out of the weblog. It’s not at all simplistic to simply choose to be handing out hints that many people might have been selling. We do understand we’ve got the website owner to give thanks to because of that. Most of the explanations you made, the straightforward site menu, the relationships you can assist to foster – it’s all fantastic, and it’s really helping our son in addition to us reason why the topic is fun, which is truly important. Thanks for the whole thing!

I visited a lot of website but I conceive this one holds something special in it in it

Merely wanna remark that you have a very decent site, I like the style it really stands out.

I loved as much as you’ll receive carried out right here. The sketch is tasteful, your authored material stylish. nonetheless, you command get bought an shakiness over that you wish be delivering the following. unwell unquestionably come further formerly again since exactly the same nearly very often inside case you shield this hike.

Enjoyed examining this, very good stuff, regards. “Success doesn’t come to you…you go to it.” by Marva Collins.

Good post and right to the point. I am not sure if this is actually the best place to ask but do you folks have any thoughts on where to employ some professional writers? Thank you 🙂

I like this post, enjoyed this one appreciate it for putting up.

F*ckin¦ amazing issues here. I am very satisfied to see your post. Thanks a lot and i am looking ahead to contact you. Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?

I appreciate, cause I found exactly what I was looking for. You have ended my four day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a nice day. Bye

I’m impressed, I must say. Really rarely do I encounter a weblog that’s both educative and entertaining, and let me inform you, you’ve hit the nail on the head. Your concept is excellent; the issue is something that not sufficient people are speaking intelligently about. I’m very comfortable that I stumbled throughout this in my search for one thing relating to this.

Lovely just what I was looking for.Thanks to the author for taking his time on this one.

You should take part in a contest for among the best blogs on the web. I’ll suggest this website!

Hello there, You’ve done a fantastic job. I will definitely digg it and personally suggest to my friends. I am sure they’ll be benefited from this web site.

Howdy very cool web site!! Man .. Beautiful .. Superb .. I’ll bookmark your blog and take the feeds additionallyKI am satisfied to find numerous useful information right here within the post, we need develop extra techniques in this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

Very interesting points you have observed, thankyou for posting.

I have been reading out a few of your posts and i must say nice stuff. I will surely bookmark your blog.

Some genuinely wondrous work on behalf of the owner of this website , dead great content material.

What’s Happening i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I have found It absolutely useful and it has helped me out loads. I hope to contribute & help other users like its aided me. Good job.

hello!,I like your writing very much! share we communicate more about your post on AOL? I need a specialist on this area to solve my problem. May be that’s you! Looking forward to see you.

Excellent goods from you, man. I’ve understand your stuff previous to and you’re just too excellent. I really like what you’ve acquired here, really like what you’re stating and the way in which you say it. You make it enjoyable and you still care for to keep it sensible. I cant wait to read far more from you. This is actually a great site.

Appreciating the dedication you put into your site and in depth information you present. It’s great to come across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the same out of date rehashed material. Wonderful read! I’ve bookmarked your site and I’m adding your RSS feeds to my Google account.

fantastic post, very informative. I wonder why the other specialists of this sector do not notice this. You must continue your writing. I am confident, you’ve a huge readers’ base already!

I reckon something genuinely special in this web site.

Very well written story. It will be useful to anyone who utilizes it, including me. Keep doing what you are doing – can’r wait to read more posts.

I couldn’t resist commenting

Regards for helping out, great info. “The four stages of man are infancy, childhood, adolescence, and obsolescence.” by Bruce Barton.

I think other website proprietors should take this web site as an model, very clean and great user genial style and design, as well as the content. You’re an expert in this topic!

Wow, fantastic blog layout! How long have you been blogging for? you make blogging look easy. The overall look of your site is wonderful, as well as the content!

Great write-up, I¦m normal visitor of one¦s blog, maintain up the excellent operate, and It is going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.

You completed several fine points there. I did a search on the subject and found the majority of persons will go along with with your blog.

I dugg some of you post as I thought they were very beneficial very beneficial

Some genuinely nice stuff on this website , I like it.

Keep working ,terrific job!

I’d perpetually want to be update on new blog posts on this web site, saved to bookmarks! .

he blog was how do i say it… relevant, finally something that helped me. Thanks

I have read some good stuff here. Certainly worth bookmarking for revisiting. I surprise how much effort you put to make such a magnificent informative website.

I like what you guys are up too. Such smart work and reporting! Keep up the excellent works guys I have incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it’ll improve the value of my site 🙂

Hmm is anyone else experiencing problems with the pictures on this blog loading? I’m trying to figure out if its a problem on my end or if it’s the blog. Any feed-back would be greatly appreciated.

I really like your writing style, wonderful info , appreciate it for posting : D.

I am often to blogging and i really appreciate your content. The article has really peaks my interest. I am going to bookmark your site and keep checking for new information.

Hiya, I am really glad I’ve found this information. Today bloggers publish just about gossips and web and this is actually annoying. A good blog with interesting content, that’s what I need. Thanks for keeping this site, I’ll be visiting it. Do you do newsletters? Can not find it.

Hey very cool website!! Man .. Beautiful .. Amazing .. I’ll bookmark your website and take the feeds also…I am happy to find a lot of useful information here in the post, we need work out more strategies in this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

Some really wonderful info , Gladiola I found this.

I will right away snatch your rss as I can’t to find your email subscription hyperlink or e-newsletter service. Do you have any? Please permit me understand in order that I may subscribe. Thanks.

Thanks for another informative web site. Where else could I get that type of info written in such an ideal way? I’ve a project that I’m just now working on, and I have been on the look out for such info.

There is noticeably a lot to identify about this. I feel you made some good points in features also.

Good write-up, I am normal visitor of one?¦s site, maintain up the excellent operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a long time.

Very interesting topic, thanks for posting.

Of course, what a magnificent site and illuminating posts, I definitely will bookmark your website.Have an awsome day!

Some really grand work on behalf of the owner of this website , perfectly outstanding subject material.

of course like your website but you have to check the spelling on quite a few of your posts. A number of them are rife with spelling problems and I in finding it very troublesome to tell the reality however I?¦ll definitely come back again.

Thanks , I’ve just been searching for information approximately this topic for a long time and yours is the best I’ve discovered till now. However, what about the conclusion? Are you positive in regards to the source?

you have a great blog here! would you like to make some invite posts on my blog?

It is really a nice and helpful piece of info. I’m glad that you shared this helpful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

Thank you for sharing excellent informations. Your website is very cool. I am impressed by the details that you’ve on this website. It reveals how nicely you understand this subject. Bookmarked this web page, will come back for more articles. You, my friend, ROCK! I found simply the information I already searched all over the place and simply could not come across. What a perfect website.

I genuinely enjoy reading through on this website, it has got great blog posts. “The living is a species of the dead and not a very attractive one.” by Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche.

What’s Happening i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I have found It absolutely helpful and it has helped me out loads. I hope to contribute & help other users like its aided me. Great job.

Great website! I am loving it!! Will come back again. I am bookmarking your feeds also

I am pleased that I detected this site, precisely the right information that I was looking for! .

Awsome article and straight to the point. I am not sure if this is really the best place to ask but do you guys have any ideea where to hire some professional writers? Thanks in advance 🙂

Good day very cool website!! Man .. Excellent .. Superb .. I will bookmark your website and take the feeds additionally?KI am happy to seek out numerous useful info here within the publish, we’d like work out more techniques in this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

I like this post, enjoyed this one appreciate it for posting. “To affect the quality of the day that is the art of life.” by Henry David Thoreau.

I think other website proprietors should take this website as an model, very clean and excellent user genial style and design, as well as the content. You are an expert in this topic!

Hey there! Quick question that’s entirely off topic. Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly? My blog looks weird when browsing from my iphone4. I’m trying to find a theme or plugin that might be able to fix this problem. If you have any suggestions, please share. Cheers!

Thanks a lot for sharing this with all of us you really know what you’re talking about! Bookmarked. Kindly also visit my web site =). We could have a link exchange agreement between us!

Greetings! I’ve been following your weblog for a long time now and finally got the courage to go ahead and give you a shout out from New Caney Tx! Just wanted to tell you keep up the good work!

Hey there! Someone in my Facebook group shared this site with us so I came to look it over. I’m definitely loving the information. I’m bookmarking and will be tweeting this to my followers! Superb blog and superb design.

Deference to op, some superb information .

Great ?V I should definitely pronounce, impressed with your site. I had no trouble navigating through all tabs as well as related info ended up being truly simple to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it in the least. Quite unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or anything, web site theme . a tones way for your customer to communicate. Excellent task..

This is very interesting, You are a very skilled blogger. I have joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your great post. Also, I have shared your website in my social networks!

I don’t even know how I stopped up here, but I thought this submit was great. I do not know who you are however definitely you’re going to a well-known blogger when you are not already 😉 Cheers!

It’s in point of fact a nice and useful piece of information. I am satisfied that you just shared this useful information with us. Please stay us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

Great post, I conceive people should learn a lot from this weblog its rattling user friendly.

Some genuinely choice posts on this site, saved to bookmarks.

you have a great blog here! would you like to make some invite posts on my blog?

I’m not that much of a internet reader to be honest but your sites really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your website to come back in the future. Cheers

I have been absent for some time, but now I remember why I used to love this web site. Thanks, I will try and check back more often. How frequently you update your web site?

This is the right blog for anyone who wants to find out about this topic. You realize so much its almost hard to argue with you (not that I actually would want…HaHa). You definitely put a new spin on a topic thats been written about for years. Great stuff, just great!

Thank you for sharing excellent informations. Your site is so cool. I’m impressed by the details that you have on this blog. It reveals how nicely you perceive this subject. Bookmarked this website page, will come back for extra articles. You, my pal, ROCK! I found simply the information I already searched everywhere and just couldn’t come across. What a great web site.

Hi , I do believe this is an excellent blog. I stumbled upon it on Yahoo , i will come back once again. Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and help other people.

It’s actually a cool and helpful piece of information. I’m glad that you simply shared this useful information with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

I truly enjoy looking through on this website , it holds excellent blog posts. “It is easy to be nice, even to an enemy – from lack of character.” by Dag Hammarskjld.

Great – I should definitely pronounce, impressed with your website. I had no trouble navigating through all the tabs as well as related information ended up being truly easy to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it in the least. Reasonably unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or anything, website theme . a tones way for your client to communicate. Excellent task..

I’d should examine with you here. Which is not something I often do! I take pleasure in reading a publish that may make people think. Also, thanks for permitting me to remark!

It’s truly a great and helpful piece of info. I’m glad that you simply shared this helpful information with us. Please stay us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

You have mentioned very interesting points! ps decent site. “Become addicted to constant and never-ending self improvement.” by Anthony D’Angelo.

I got what you intend,saved to my bookmarks, very decent internet site.

Great awesome things here. I?¦m very glad to look your post. Thank you a lot and i’m taking a look forward to touch you. Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?

Excellent beat ! I wish to apprentice while you amend your website, how can i subscribe for a blog web site? The account aided me a acceptable deal. I had been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast provided bright clear concept

whoah this blog is fantastic i love studying your articles. Keep up the great work! You already know, many persons are looking round for this info, you could aid them greatly.

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found that it’s truly informative. I am gonna watch out for brussels. I will appreciate if you continue this in future. Lots of people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

You could certainly see your skills within the work you write. The sector hopes for even more passionate writers such as you who are not afraid to say how they believe. Always follow your heart.

I have been surfing online greater than 3 hours lately, but I by no means discovered any attention-grabbing article like yours. It?¦s beautiful worth sufficient for me. Personally, if all site owners and bloggers made good content material as you did, the internet will be a lot more useful than ever before.

You can definitely see your enthusiasm within the paintings you write. The world hopes for more passionate writers such as you who aren’t afraid to say how they believe. At all times go after your heart. “Man is the measure of all things.” by Protagoras.

Great post. I was checking constantly this blog and I’m impressed! Very useful info particularly the last part 🙂 I care for such info a lot. I was seeking this particular information for a very long time. Thank you and best of luck.

After research just a few of the blog posts on your web site now, and I really like your manner of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark web site record and shall be checking again soon. Pls check out my web page as effectively and let me know what you think.

Usually I do not read post on blogs, but I wish to say that this write-up very forced me to try and do it! Your writing taste has been amazed me. Thanks, quite nice post.

I believe this internet site contains some real wonderful info for everyone : D.

Good write-up, I am normal visitor of one?¦s web site, maintain up the excellent operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.

Thank you for some other informative site. The place else may I am getting that type of info written in such a perfect means? I’ve a challenge that I am just now working on, and I have been at the glance out for such information.

I’ve read a few good stuff here. Certainly worth bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how much effort you put to make such a excellent informative site.

I truly appreciate this post. I have been looking all over for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You have made my day! Thanks again

you’re in reality a just right webmaster. The web site loading velocity is amazing. It seems that you are doing any distinctive trick. In addition, The contents are masterpiece. you have done a excellent activity on this topic!

Hey! I know this is kinda off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could locate a captcha plugin for my comment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having trouble finding one? Thanks a lot!

It’s actually a great and useful piece of information. I’m happy that you shared this useful information with us. Please stay us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

I have recently started a blog, the info you provide on this web site has helped me greatly. Thank you for all of your time & work.

It’s really a great and useful piece of information. I’m glad that you simply shared this useful information with us. Please stay us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

Hello, you used to write magnificent, but the last several posts have been kinda boring?K I miss your great writings. Past several posts are just a little out of track! come on!

Hello there, You’ve done a fantastic job. I will definitely digg it and personally suggest to my friends. I am sure they will be benefited from this site.

Great write-up, I am normal visitor of one?¦s website, maintain up the excellent operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.

I love forgathering utile information , this post has got me even more info! .

Thanks, I’ve just been searching for information about this topic for ages and yours is the best I have discovered so far. But, what concerning the conclusion? Are you sure in regards to the supply?

Wow that was unusual. I just wrote an really long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Anyhow, just wanted to say wonderful blog!

he blog was how do i say it… relevant, finally something that helped me. Thanks

Very interesting information!Perfect just what I was searching for!

Thanks for helping out, wonderful info. “The laws of probability, so true in general, so fallacious in particular.” by Edward Gibbon.

I like your writing style really loving this internet site.

I truly appreciate this post. I¦ve been looking all over for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You’ve made my day! Thanks again

Heya i’m for the primary time here. I came across this board and I find It truly useful & it helped me out a lot. I hope to present one thing back and help others such as you aided me.

I’m impressed, I must say. Really hardly ever do I encounter a blog that’s each educative and entertaining, and let me tell you, you’ve gotten hit the nail on the head. Your idea is outstanding; the problem is something that not enough persons are speaking intelligently about. I am very completely happy that I stumbled across this in my search for one thing referring to this.

Hey there! I’ve been following your blog for some time now and finally got the bravery to go ahead and give you a shout out from Porter Texas! Just wanted to say keep up the good work!

I?¦ll immediately grab your rss feed as I can’t find your email subscription hyperlink or e-newsletter service. Do you have any? Please allow me recognize so that I may subscribe. Thanks.

I’m curious to find out what blog platform you are working with? I’m experiencing some small security issues with my latest site and I’d like to find something more safe. Do you have any solutions?

I was very pleased to find this web-site.I wanted to thanks for your time for this wonderful read!! I definitely enjoying every little bit of it and I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you blog post.

Great wordpress blog here.. It’s hard to find quality writing like yours these days. I really appreciate people like you! take care

Enjoyed examining this, very good stuff, thankyou.

I keep listening to the news broadcast lecture about receiving free online grant applications so I have been looking around for the top site to get one. Could you advise me please, where could i find some?

You are my inspiration , I have few blogs and sometimes run out from to brand.

What i do not understood is in truth how you’re no longer actually a lot more smartly-liked than you may be right now. You are so intelligent. You realize thus considerably on the subject of this subject, made me for my part imagine it from numerous various angles. Its like men and women are not involved unless it is one thing to accomplish with Woman gaga! Your own stuffs nice. All the time handle it up!

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain nice points in features also.

You can certainly see your skills within the work you write. The world hopes for even more passionate writers such as you who aren’t afraid to mention how they believe. All the time go after your heart.

Wow! Thank you! I continually wanted to write on my site something like that. Can I take a fragment of your post to my blog?

Have you ever considered about including a little bit more than just your articles? I mean, what you say is fundamental and everything. However think of if you added some great photos or video clips to give your posts more, “pop”! Your content is excellent but with images and video clips, this website could certainly be one of the best in its niche. Great blog!

You could definitely see your enthusiasm within the work you write. The sector hopes for even more passionate writers like you who aren’t afraid to say how they believe. All the time follow your heart. “There are only two industries that refer to their customers as users.” by Edward Tufte.

Hi, i feel that i saw you visited my web site thus i came to “go back the desire”.I’m trying to to find issues to improve my site!I suppose its good enough to make use of a few of your ideas!!

wonderful points altogether, you simply gained a brand new reader. What would you suggest in regards to your post that you made some days ago? Any positive?

Glad to be one of several visitants on this amazing internet site : D.

An impressive share, I just given this onto a colleague who was doing a little bit analysis on this. And he actually bought me breakfast as a result of I discovered it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the treat! But yeah Thnkx for spending the time to discuss this, I feel strongly about it and love studying more on this topic. If doable, as you turn out to be experience, would you mind updating your weblog with more details? It’s extremely useful for me. Big thumb up for this weblog put up!

Greetings! I’ve been reading your blog for some time now and finally got the bravery to go ahead and give you a shout out from New Caney Tx! Just wanted to say keep up the good job!

This is the right blog for anyone who wants to find out about this topic. You realize so much its almost hard to argue with you (not that I actually would want…HaHa). You definitely put a new spin on a topic thats been written about for years. Great stuff, just great!

Really great visual appeal on this internet site, I’d value it 10 10.

Utterly indited content material, thankyou for information .

I conceive you have remarked some very interesting points, regards for the post.

You are my inspiration , I possess few blogs and very sporadically run out from to post .

Definitely, what a magnificent blog and illuminating posts, I surely will bookmark your site.All the Best!

I truly appreciate this post. I have been looking all over for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You have made my day! Thank you again!

It’s hard to find knowledgeable people on this topic, but you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

Some really wonderful info , Glad I detected this. “Use your imagination not to scare yourself to death but to inspire yourself to life.” by Adele Brookman.

Perfect piece of work you have done, this site is really cool with good information.

Helpful information. Lucky me I found your site unintentionally, and I am shocked why this coincidence did not came about earlier! I bookmarked it.

Great wordpress blog here.. It’s hard to find quality writing like yours these days. I really appreciate people like you! take care

Great blog! Do you have any helpful hints for aspiring writers? I’m hoping to start my own site soon but I’m a little lost on everything. Would you advise starting with a free platform like WordPress or go for a paid option? There are so many options out there that I’m completely confused .. Any suggestions? Many thanks!

Hi! I know this is kinda off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could find a captcha plugin for my comment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having problems finding one? Thanks a lot!

I like what you guys are up also. Such clever work and reporting! Keep up the excellent works guys I have incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it will improve the value of my web site 🙂

Very good blog you have here but I was curious about if you knew of any discussion boards that cover the same topics discussed here? I’d really love to be a part of community where I can get opinions from other knowledgeable people that share the same interest. If you have any recommendations, please let me know. Kudos!

Good write-up, I am normal visitor of one’s web site, maintain up the nice operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a long time.

Pretty section of content. I just stumbled upon your site and in accession capital to claim that I acquire in fact enjoyed account your weblog posts. Any way I will be subscribing to your feeds or even I success you get admission to consistently quickly.

Hey! I’m at work surfing around your blog from my new iphone! Just wanted to say I love reading your blog and look forward to all your posts! Keep up the superb work!

Wonderful beat ! I wish to apprentice while you amend your site, how could i subscribe for a weblog website? The account helped me a appropriate deal. I had been tiny bit familiar of this your broadcast provided vibrant transparent idea

I wanted to thank you for this great read!! I definitely enjoying every little bit of it I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you post…

An impressive share, I just given this onto a colleague who was doing a little analysis on this. And he in fact bought me breakfast because I found it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the treat! But yeah Thnkx for spending the time to discuss this, I feel strongly about it and love reading more on this topic. If possible, as you become expertise, would you mind updating your blog with more details? It is highly helpful for me. Big thumb up for this blog post!

I have recently started a site, the information you provide on this website has helped me tremendously. Thank you for all of your time & work.

You actually make it seem really easy together with your presentation however I to find this matter to be actually something which I believe I’d by no means understand. It kind of feels too complex and very huge for me. I’m having a look ahead on your subsequent publish, I’ll try to get the dangle of it!

Very interesting information!Perfect just what I was looking for!

I have read a few good stuff here. Definitely worth bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how so much attempt you put to create one of these excellent informative site.

hey there and thank you for your info – I’ve definitely picked up anything new from right here. I did however expertise a few technical issues using this website, as I experienced to reload the site lots of times previous to I could get it to load correctly. I had been wondering if your hosting is OK? Not that I am complaining, but slow loading instances times will often affect your placement in google and can damage your high-quality score if advertising and marketing with Adwords. Anyway I am adding this RSS to my email and could look out for much more of your respective intriguing content. Ensure that you update this again soon..

Great post, I think people should larn a lot from this website its rattling user genial.

I’ve read a few good stuff here. Certainly worth bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how much effort you put to make such a wonderful informative website.

As I site possessor I believe the content matter here is rattling magnificent , appreciate it for your hard work. You should keep it up forever! Best of luck.

Enjoyed examining this, very good stuff, regards. “It requires more courage to suffer than to die.” by Napoleon Bonaparte.

I’m truly enjoying the design and layout of your blog. It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more pleasant for me to come here and visit more often. Did you hire out a developer to create your theme? Fantastic work!

great post, very informative. I wonder why the other specialists of this sector don’t notice this. You should continue your writing. I am confident, you’ve a huge readers’ base already!

Great write-up, I¦m regular visitor of one¦s site, maintain up the nice operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a long time.

What¦s Happening i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I have discovered It positively helpful and it has aided me out loads. I’m hoping to contribute & aid other customers like its aided me. Good job.

You made some nice points there. I did a search on the subject and found most persons will agree with your blog.

I like this post, enjoyed this one thanks for posting. “Pain is inevitable. Suffering is optional.” by M. Kathleen Casey.

Italian goldsmiths 10 years specializes in Locket Pendants and memorial jewelry. ArsAura · Colleras, gemelos-Cufflinks-Gemelli artigianali.

Only a smiling visitant here to share the love (:, btw outstanding pattern.

I wish to express some thanks to you just for bailing me out of this issue. Because of surfing around throughout the world wide web and obtaining thoughts that were not productive, I was thinking my entire life was gone. Living minus the solutions to the issues you have sorted out all through the write-up is a critical case, and the kind which may have in a wrong way damaged my career if I hadn’t discovered the blog. Your talents and kindness in dealing with the whole thing was excellent. I don’t know what I would’ve done if I had not discovered such a thing like this. I’m able to at this time look forward to my future. Thank you very much for this high quality and effective help. I will not hesitate to endorse your web sites to any person who should receive care on this topic.

Please let me know if you’re looking for a article writer for your weblog. You have some really good posts and I feel I would be a good asset. If you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d really like to write some content for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine. Please send me an email if interested. Kudos!

It?¦s truly a great and helpful piece of information. I am satisfied that you simply shared this helpful info with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

Very interesting information!Perfect just what I was searching for!

I have been browsing online greater than 3 hours these days, yet I never discovered any fascinating article like yours. It is lovely price enough for me. Personally, if all site owners and bloggers made just right content material as you did, the web will be much more useful than ever before.

Incredible! This blog looks exactly like my old one! It’s on a entirely different topic but it has pretty much the same layout and design. Excellent choice of colors!

excellent points altogether, you simply gained a new reader. What would you suggest about your post that you made some days ago? Any positive?

UTS~I know it’s crazy! But that’s the plan. Tell him BrotherKomarade you know the deal! PSBO & Company are socialist who believe that tax breaks for businesses, small business owners and upper-middle-class workers will not “trickle-down,” while taxing businesses and upper-middle-class workers, and giving tax breaks to people who pay little or no taxes, will somehow “trickle-up!” So yeah you are right they are CRAZY AS HELL.

This blog is definitely rather handy since I’m at the moment creating an internet floral website – although I am only starting out therefore it’s really fairly small, nothing like this site. Can link to a few of the posts here as they are quite. Thanks much. Zoey Olsen

I was studying some of your blog posts on this website and I think this internet site is real instructive! Keep on putting up.

What i don’t understood is in fact how you are not actually much more well-liked than you may be right now. You’re very intelligent. You understand therefore considerably relating to this matter, produced me for my part imagine it from so many numerous angles. Its like men and women don’t seem to be fascinated until it is something to do with Lady gaga! Your individual stuffs great. At all times take care of it up!

Hi! I know this is kinda off topic however I’d figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in trading links or maybe guest authoring a blog article or vice-versa? My blog goes over a lot of the same topics as yours and I think we could greatly benefit from each other. If you might be interested feel free to shoot me an email. I look forward to hearing from you! Wonderful blog by the way!

I am often to blogging and i really appreciate your content. The article has really peaks my interest. I am going to bookmark your site and keep checking for new information.

Very interesting topic, thankyou for putting up. “Education a debt due from present to future generations.” by George Peabody.

Hi there, just became alert to your blog through Google, and found that it is really informative. I’m going to watch out for brussels. I’ll appreciate if you continue this in future. Numerous people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

An impressive share, I just given this onto a colleague who was doing a little analysis on this. And he in fact bought me breakfast because I found it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the treat! But yeah Thnkx for spending the time to discuss this, I feel strongly about it and love reading more on this topic. If possible, as you become expertise, would you mind updating your blog with more details? It is highly helpful for me. Big thumb up for this blog post!

Thanks for this fantastic post, I am glad I detected this internet site on yahoo.

Very good post.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

My website: русский инцест

We’re a bunch of volunteers and opening a brand new scheme in our community. Your web site offered us with valuable info to work on. You’ve performed an impressive process and our whole community will be grateful to you.

I really prize your work, Great post.

Nice post. I was checking continuously this blog and I’m impressed! Extremely helpful info particularly the closing section 🙂 I maintain such info a lot. I used to be seeking this certain info for a long time. Thank you and best of luck.

Howdy! I’m at work browsing your blog from my new apple iphone! Just wanted to say I love reading through your blog and look forward to all your posts! Carry on the excellent work!

This really answered my problem, thank you!

Great blog here! Also your site loads up fast! What host are you using? Can I get your affiliate link to your host? I wish my website loaded up as fast as yours lol

I will immediately snatch your rss as I can not find your e-mail subscription link or newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Kindly permit me recognise so that I could subscribe. Thanks.

I have been surfing online greater than three hours lately, yet I by no means found any fascinating article like yours. It’s pretty price enough for me. Personally, if all website owners and bloggers made just right content material as you probably did, the net will likely be much more helpful than ever before. “Nothing will come of nothing.” by William Shakespeare.

Your style is so unique compared to many other people. Thank you for publishing when you have the opportunity,Guess I will just make this bookmarked.2

Saved as a favorite, I really like your blog!

A lot of blog writers nowadays yet just a few have blog posts worth spending time on reviewing.

My website: би порно

You have observed very interesting details! ps decent web site.

Useful information. Fortunate me I discovered your site accidentally, and I’m surprised why this coincidence did not happened earlier! I bookmarked it.

good post.Never knew this, thankyou for letting me know.

I?¦ve recently started a blog, the info you offer on this site has helped me tremendously. Thanks for all of your time & work.

you will have an important blog here! would you like to make some invite posts on my weblog?

I would like to thnkx for the efforts you have put in writing this blog. I am hoping the same high-grade blog post from you in the upcoming as well. In fact your creative writing abilities has inspired me to get my own blog now. Really the blogging is spreading its wings quickly. Your write up is a good example of it.

Heya i am for the first time here. I found this board and I find It really useful & it helped me out a lot. I hope to provide one thing back and aid others like you aided me.

Hey, you used to write great, but the last several posts have been kinda boring?K I miss your super writings. Past few posts are just a little bit out of track! come on!

Great ?V I should certainly pronounce, impressed with your web site. I had no trouble navigating through all tabs and related info ended up being truly easy to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it in the least. Quite unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or anything, site theme . a tones way for your client to communicate. Nice task..

Hmm it looks like your site ate my first comment (it was super long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I submitted and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I too am an aspiring blog writer but I’m still new to the whole thing. Do you have any points for inexperienced blog writers? I’d definitely appreciate it.

Hello There. I discovered your weblog using msn. That is an extremely well written article. I will make sure to bookmark it and come back to learn more of your helpful info. Thank you for the post. I will certainly comeback.

Очень полезная информация о том, какие категории объявлений наиболее популярны на досках объявлений.

I must express thanks to the writer for bailing me out of this crisis. Right after scouting throughout the online world and coming across views which were not helpful, I believed my life was well over. Being alive devoid of the solutions to the issues you’ve sorted out all through your post is a crucial case, and those which could have negatively affected my career if I hadn’t come across your web site. Your own personal competence and kindness in dealing with almost everything was valuable. I don’t know what I would’ve done if I had not discovered such a thing like this. I can also at this point look forward to my future. Thanks for your time very much for the skilled and amazing guide. I won’t think twice to recommend your web page to anyone who should get tips on this situation.

I love it when people come together and share opinions, great blog, keep it up.

I conceive this internet site has got some really excellent info for everyone. “The penalty of success is to be bored by the attentions of people who formerly snubbed you.” by Mary Wilson Little.

I do agree with all of the ideas you have presented in your post. They are really convincing and will certainly work. Still, the posts are too short for starters. Could you please extend them a bit from next time? Thanks for the post.

It is really a great and useful piece of info. I am glad that you shared this useful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

This actually answered my drawback, thank you!

I have not checked in here for some time as I thought it was getting boring, but the last several posts are good quality so I guess I will add you back to my daily bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

hi!,I really like your writing very much! percentage we keep in touch extra about your article on AOL? I need an expert on this space to unravel my problem. Maybe that’s you! Taking a look forward to see you.

Wonderful website you have here but I was curious if you knew of any community forums that cover the same topics talked about in this article? I’d really love to be a part of online community where I can get opinions from other knowledgeable people that share the same interest. If you have any recommendations, please let me know. Thank you!

Do you have a spam problem on this blog; I also am a blogger, and I was wanting to know your situation; we have created some nice procedures and we are looking to swap solutions with other folks, please shoot me an email if interested.

Thankyou for this marvellous post, I am glad I discovered this website on yahoo.