This week the Lonmin PLC mining company gives evidence at the Marikana Commission of Inquiry. Recently we ran a story delving into the real cost of Platinum to our nation. In this leading article for The Journalist the world renowned Dr Sophia Kisting, Occupational Medicine Specialist and former Director of the ILO Global Programme on HIV/AIDS, reports on the findings of a group of eminent experts.

These reflections on visits to the Wonderkop, Marikana area are in recognition and support of The Journalist’s excellent report to mark the second anniversary of the Marikana tragedy, The real price of platinum – squalor in the midst of immense wealth. I would like to concur and support the views and perspectives of Chris Molebatsi and David van Wyk in the above-named report.

I had the opportunity to visit, with Eugene Cairncross, the Wonderkop, Marikana area more than once on behalf of the People’s Health Movement (PHM) in collaboration with the Bench Marks Foundation (BMF). The following observations and perspectives are informed by the interviews with community members and workers about their occupational and environmental health concerns, related to platinum mining.

This overview draws on the PHM background paper on the extractive industries for the Lancet Commission Report on the Global Governance for Health. The direct experience of the interviewees can only reflect a small part of the total reality of platinum mining, but their stories reflect both their dire present circumstances and the ghosts and memories of the past.

(Ed Note: Eugene Cairncross is a former Professor in the Department of Chemical Engineering at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology. He is a member of the People’s Health Movement.)

There is a road in Gauteng all along the old gold reef, the foundation of the mining industry. Along this road there are 600 abandoned mines. Photo courtesy David van Wyk.

The visit to the Marikana area came after I spent over six years in the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in Geneva. During this time I had the opportunity to visit and work at numerous workplaces in many industrialised and less industrialised countries. My experience was that good occupational and environmental health and safety practices are influenced by a number of factors.

These, amongst others include:

- good legislation and good practical implementation of policies agreed upon by workers and employers and which support decent work and salaries;

- a strong motivated inspectorate;

- effective and efficient enforcement of legislation;

- meaningful ongoing training for all workers and all managers and ongoing skills development;

- a good functioning compensation system which underpins PREVENTION;

- the protection of human rights and the necessary financial resources. More important than the financial resources was the collective and interdependent mindset that death, diseases and injuries from work is totally unacceptable and can be PREVENTED.

Not once did I gain the impression that as a country we are less capable than any other to implement these factors effectively and efficiently. Our very history can and should be our inspiration to excel in healthy and safe environments and workplaces. We can set a proud and leading example amongst the nations of the world.

Unfortunately, on arrival at the Marikana area I was shocked at the very obvious signs of ongoing inequality and deprivation. What we observed and what we learnt from our interactions with workers and communities was traumatic and very disappointing as it is eminently possible to change working and environmental conditions for the better, for our common humanity and for sustainable development.

Unreformed system perpetuating inequality

It was shocking to see so much evidence of the apartheid style migrant labour system that is in place in the platinum belt. Many workers come from other parts of South Africa or from neighbouring countries. The living-out allowance that was meant to address, in part, the inhuman single-sex hostel system of apartheid is woefully inadequate and has helped to perpetuate further uncertainty, lack of sustainability and backyard dwellings with lack of infra-structure to support residents.

The system of increasing sub-contracting and labour-brokering is making the effects of the migrant labour system, as practiced in the platinum belt, much worse. Many workers are employed through subcontractors and labour brokers. Their wages are meagre and they have limited work benefits. From the reports of families of mineworkers employed through labour brokers it is clear that they cannot escape abject poverty on the wages earned. We learnt of one such family where a young man who completed matric and qualified to go to university, could not do so. He tried to start his own business which was broken into repeatedly. In despair he took his own life by burning himself with paraffin.

Gauteng’s Mining Wasteland. Photo courtesy David van Wyk.

Conditions & Compensation

The Annual Report of the Department of Mineral Resources for 2012-2013 indicate there were 28 deaths and 1 360 injuries reported in platinum mines for 2012 (keeping in mind that some mines may not have sent in reports).

The overall number of deaths in the mining sector has been decreasing systematically over the past years and this indicates better safety standards and it is commendable. However, every death at work is a tragedy that is unacceptable because it is PREVENTABLE. More so since the profit margins in platinum mining are of such a magnitude that safety can be guaranteed.

The tragic loss of life at Marikana for communities and workers and their families are work-related. Should the 44 people who so tragically died be added to the reports of fatalities the platinum mines send in to the Department of Mineral Resources?

In addition, we have the other tragedy of significant loss of life in abandoned mines where the miners are termed “illegal”? This however, is mining related and should mine owners not take greater responsibility for the safety of abandoned mine shafts?

Surely, we are all equal and every death at work diminishes all of us?

The Annual Report of the Department of Mineral Resources for 2011-2012 indicates that platinum mines reported for 2011 the diagnosis of:

- 129 workers with silicosis

- 1 005 with Pulmonary Tuberculosis and

- 367 with Noise Induced Hearing Loss

As with deaths and injuries these diseases are totally PREVENTABLE. There are countries in the world who have managed to eliminate silicosis through adequate control measures. However, we are not winning the battle with occupational diseases.

The report further indicates very high levels of silica dust in several mines as well as excessive heat and noise. This is all the more distressing as our occupational exposure limit (known as oel) is far higher than what the World Health Organisation (WHO) considers to be a protective level.

It is important to state that silica dust in the lungs predispose workers to Pulmonary TB and if we do not control the dust more workers and their families will continue to develop pulmonary TB. Why should poor underpaid workers develop these diseases that constitute almost silent epidemics in our country in the 21st century?

The mining sector has the financial resources, the technical know-how, and our country has the knowledge and human resource capacity to PREVENT this. The parliamentary report of the Minister of Health, Dr Aaron Motsoaledi during his budget speech in 2014 described the magnitude of the TB problem in the mining sector as a whole:

“It is the highest incidence of TB in any working population in the world. It affects 500 000 mineworkers, their 230 000 partners, and 700 000 children.”

When PREVENTION and hazard control mechanisms fail at work, sick or injured workers are entitled to compensation. Unfortunately there are tens of thousands of workers with occupational (work-related) mining diseases living mainly in poor rural areas with inadequate access to health services. The majority of them have never received the compensation, as little as it is, that is due to them. The amount of money that the mining sector pays towards compensation is totally inadequate for the true cost of ill-health that is caused by this sector and is therefore not an incentive to PREVENT disease. The compensation system is fragmented and not functioning efficiently and effectively at all.

A collaborative, inclusive and interdependent approach amongst different government departments can successfully address the current failures of the compensation system. Once again, as a country we have the leadership, the requisite knowledge, skills, technical and economic resources to run a well functioning compensation system which can contribute in a major way to PREVENTION of ill-health, job security and sustainable industries.

The mining sector unfortunately have mostly externalised the health and environmental cost of their industries to the public sector, to workers, their families and to communities. They often deny and suppress the evidence demonstrating the causal relationship between exposure to mining hazards and adverse health outcome. They deny the huge contribution that the mining industry makes to the high burden of disease in the public health sector in South Africa. This is unnecessary and is a sad legacy of our divided past. Collectively and with the necessary dialogue and focus we can overcome this.

Most importantly, health workers are not effectively trained to recognise, diagnose and prevent occupational and environmental diseases even when they work right next to the mines and factories. If the many work-related diseases are not diagnosed and help us all become aware of the magnitude of the problem we lose a great opportunity in PREVENTION and fail to reduce the burden of disease in the public sector. Our schools, our colleges and our universities need to look into training curricula as a matter of great urgency to address this major shortcoming.

Women and platinum mining

Our democracy now makes it possible for women to work underground in mines. This is a big step forward but interviews reflect that they face many challenges in the mines. This is related to their relative small numbers underground as well as patriarchal societal norms practiced by mine management and by fellow workers. It is clear that ongoing monitoring and evaluation is necessary to enable women to benefit from a workplace free from harassment and lack of safe and adequate ablution facilities.

Interviewees related the problems of sex work in the platinum belt and the exposure of women and men to the risk of HIV and AIDS. The migrant labour system and conditions of work and living increases vulnerability to HIV, AIDS and TB.

Land rights vs mining rights

For kilometre upon kilometre in the platinum belt the land is covered with extensive dusty mine dumps and tailings dams. These are a blot on the striking beauty of the landscape. Many communities live in close proximity of the dumps and the mines and inhales the fine particles of the dust every day. There is evidence of many abandoned homes and of untended crops now growing behind razor wire enclosures with unfriendly warning signs. There is the ever presence of private security personnel behaving no differently than the police in the hey-day of apartheid.

Workers and community members tell of a sense of being engulfed in violence ever since the massacre. Amongst the most painful recollections of community members are those related to being moved off the productive land they lived on for generations into essentially squatter settlements to make way for platinum mining.

“We are victims of mining relocation in pursuit of the white gold called platinum,” says a worker.

The mine provides inferior zinc housing, few communal taps and no electricity. No refuse removal or adequate sewage systems are put in place. Many toilets overflow and streams of polluted water are evident creating major health hazards, especially for children. Unemployment is rife, further perpetuating the evidence of marked inequality.

Communities mostly have no electricity and have to use paraffin. One young woman was severely burnt. The stove was supplied by the mining company. There are endless problems with paraffin cooking and some houses have burnt down.

Questions of the land and mining remains unresolved and emotions related to the land runs very deep. The urgent quest of communities to have a meaningful say in the question of mining on land where they live is a fundamental human right that we can and should respect. We otherwise perpetuate the unequal practices of a past we all wish to redress. Many relocated community members have lost their livelihoods and they report that it is common practice of mine-owners not to employ members of the local communities.

Eugene Cairncross presentation on behalf of the People’s Health Movement (PHM).

Children Have Drowned

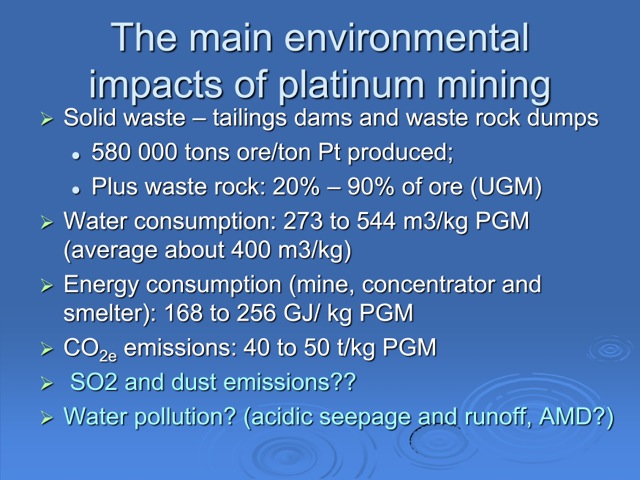

The health, socio-economic and environmental impacts of platinum mining occur throughout every phase of its life cycle, from the cradle of exploration to the grave (and beyond) of abandoned mine shafts, disowned mountains of waste rock, tailings dams and lakes of polluted water.

Solid waste from underground result in extensive mountains of rock dumps covering land that was previously used for food production. The environmental pollution is extensive as about 18 tons of ore has to be processed to obtain one ounce of platinum ( (about 98% of the ore become dumps on the land).

There is excessive water and energy consumption by the mines while communities are in almost constant want of water and electricity. There are excessive and inadequately controlled Sulphur Dioxide (SO2) emissions from the smelters with resultant negative health effects especially on children, the elderly and people with lung problems. Water pollution through acidic seepage and runoff result in acid mine drainage. Community members complain that they have no reports from the mines to show that the emissions or the dust is controlled to reassure them that they and their children are safe from the environmental hazards of platinum mining.

They complain of blasting at the mines which take place at regular intervals and houses shake each time. Cracks are evident in many of them. The mine smelters burn day and night and the release of carbon dioxide and sulphur dioxide remains a constant uncertainty and major health risk for community members.

Children have drowned in unprotected mine dams and community members say these tragedies happen because the mine owners and mine management do not engage with them in any meaningful manner.

In the long term a much larger population is likely to be affected by the legacy of a devastated environment for decades and centuries after platinum mining has ceased. Unless work and environmental problems are addressed a concomitant legacy of platinum mining is that of huge numbers of unemployed workers and disrupted (mainly rural) societies, and a burden of disease and poverty suffered by both current and former mine workers and successive generations of their families.

I’m usually to running a blog and i actually recognize your content. The article has really peaks my interest. I’m going to bookmark your site and maintain checking for new information.

Hey very nice blog!! Man .. Excellent .. Superb .. I will bookmark your web site and take the feeds also…I am glad to find a lot of useful info right here within the put up, we need work out more strategies on this regard, thanks for sharing.

Please let me know if you’re looking for a article writer for your weblog. You have some really great articles and I think I would be a good asset. If you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d absolutely love to write some material for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine. Please shoot me an email if interested. Many thanks!

I’m truly enjoying the design and layout of your site. It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more enjoyable for me to come here and visit more often. Did you hire out a designer to create your theme? Superb work!

Thanks for sharing excellent informations. Your web site is so cool. I’m impressed by the details that you have on this web site. It reveals how nicely you understand this subject. Bookmarked this website page, will come back for extra articles. You, my friend, ROCK! I found simply the info I already searched everywhere and just could not come across. What an ideal site.

Great awesome issues here. I am very happy to see your article. Thank you so much and i’m looking forward to touch you. Will you please drop me a e-mail?

Do you have a spam problem on this website; I also am a blogger, and I was curious about your situation; many of us have created some nice procedures and we are looking to swap solutions with other folks, why not shoot me an e-mail if interested.

You got a very good website, Glad I noticed it through yahoo.

I’m not sure why but this website is loading extremely slow for me. Is anyone else having this issue or is it a problem on my end? I’ll check back later and see if the problem still exists.

Good website! I really love how it is simple on my eyes and the data are well written. I am wondering how I might be notified whenever a new post has been made. I have subscribed to your feed which must do the trick! Have a great day!

Really wonderful info can be found on web site.

Nice post. I learn something more challenging on different blogs everyday. It will always be stimulating to read content from other writers and practice a little something from their store. I’d prefer to use some with the content on my blog whether you don’t mind. Natually I’ll give you a link on your web blog. Thanks for sharing.

Hello! I know this is kinda off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could locate a captcha plugin for my comment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having problems finding one? Thanks a lot!

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across. It extremely helps make reading your blog significantly easier.

Magnificent website. A lot of useful information here. I’m sending it to some buddies ans additionally sharing in delicious. And certainly, thank you in your sweat!

Lovely just what I was searching for.Thanks to the author for taking his time on this one.

Hi my friend! I want to say that this post is awesome, great written and include approximately all vital infos. I would like to see extra posts like this .

A formidable share, I simply given this onto a colleague who was doing somewhat evaluation on this. And he actually bought me breakfast as a result of I discovered it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the deal with! However yeah Thnkx for spending the time to discuss this, I feel strongly about it and love reading more on this topic. If potential, as you grow to be expertise, would you mind updating your weblog with more particulars? It’s highly useful for me. Large thumb up for this blog post!

Hey there! Would you mind if I share your blog with my facebook group? There’s a lot of folks that I think would really enjoy your content. Please let me know. Many thanks

Absolutely written content, appreciate it for entropy. “The bravest thing you can do when you are not brave is to profess courage and act accordingly.” by Corra Harris.

As I website possessor I believe the content material here is rattling great , appreciate it for your efforts. You should keep it up forever! Good Luck.

I really like foregathering useful information , this post has got me even more info! .

What i don’t realize is if truth be told how you are no longer really a lot more smartly-favored than you might be right now. You are so intelligent. You know thus significantly in relation to this matter, made me for my part imagine it from numerous numerous angles. Its like men and women don’t seem to be involved until it is one thing to do with Lady gaga! Your own stuffs outstanding. All the time care for it up!

With havin so much content do you ever run into any issues of plagorism or copyright infringement? My site has a lot of completely unique content I’ve either written myself or outsourced but it looks like a lot of it is popping it up all over the web without my authorization. Do you know any techniques to help prevent content from being stolen? I’d certainly appreciate it.

This web site is really a walk-through for all of the info you wanted about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse here, and you’ll definitely discover it.

F*ckin’ remarkable things here. I am very satisfied to see your article. Thanks so much and i am having a look forward to touch you. Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?

I like this weblog very much, Its a really nice situation to read and obtain information. “Reason is not measured by size or height, but by principle.” by Epictetus.

I used to be very pleased to seek out this net-site.I wanted to thanks for your time for this glorious learn!! I positively enjoying every little bit of it and I’ve you bookmarked to check out new stuff you weblog post.

Hey there just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The text in your content seem to be running off the screen in Opera. I’m not sure if this is a formatting issue or something to do with internet browser compatibility but I thought I’d post to let you know. The layout look great though! Hope you get the problem fixed soon. Cheers

so much wonderful info on here, : D.

Nice read, I just passed this onto a friend who was doing some research on that. And he just bought me lunch because I found it for him smile Thus let me rephrase that: Thanks for lunch! “Whenever you have an efficient government you have a dictatorship.” by Harry S Truman.

I have been browsing online more than 3 hours as of late, but I by no means discovered any attention-grabbing article like yours. It¦s beautiful value sufficient for me. Personally, if all website owners and bloggers made excellent content material as you probably did, the net can be much more useful than ever before.

Very interesting topic, regards for posting. “Stranger in a strange country.” by Sophocles.

I think other web-site proprietors should take this website as an model, very clean and excellent user friendly style and design, let alone the content. You are an expert in this topic!

Greetings! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a team of volunteers and starting a new initiative in a community in the same niche. Your blog provided us valuable information to work on. You have done a marvellous job!

Wow! This can be one particular of the most beneficial blogs We have ever arrive across on this subject. Basically Magnificent. I am also an expert in this topic so I can understand your hard work.

After study a few of the blog posts on your website now, and I truly like your way of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website list and will be checking back soon. Pls check out my web site as well and let me know what you think.

Hello. splendid job. I did not anticipate this. This is a impressive story. Thanks!

There is clearly a bundle to realize about this. I suppose you made various nice points in features also.

This is the right blog for anyone who wants to find out about this topic. You realize so much its almost hard to argue with you (not that I actually would want…HaHa). You definitely put a new spin on a topic thats been written about for years. Great stuff, just great!

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found that it is really informative. I’m going to watch out for brussels. I will appreciate if you continue this in future. Numerous people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

I dugg some of you post as I cerebrated they were invaluable handy

Please let me know if you’re looking for a article author for your blog. You have some really great posts and I feel I would be a good asset. If you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d love to write some articles for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine. Please blast me an e-mail if interested. Many thanks!

Those are yours alright! . We at least need to get these people stealing images to start blogging! They probably just did a image search and grabbed them. They look good though!

I’m curious to find out what blog system you happen to be utilizing? I’m having some small security issues with my latest blog and I’d like to find something more risk-free. Do you have any solutions?

I happen to be writing to make you understand what a brilliant encounter my princess encountered studying the blog. She mastered some details, which included what it’s like to possess an ideal helping spirit to have others without hassle have an understanding of some extremely tough issues. You really exceeded visitors’ desires. Thanks for churning out the productive, dependable, revealing and also easy tips about your topic to Tanya.

You made some clear points there. I did a search on the subject matter and found most persons will consent with your blog.

Hello. fantastic job. I did not anticipate this. This is a excellent story. Thanks!

I enjoy you because of each of your hard work on this web site. Ellie loves setting aside time for investigation and it’s easy to understand why. A number of us learn all about the dynamic tactic you render invaluable techniques via the blog and as well cause response from some others on the subject matter so our favorite child is actually being taught a lot of things. Take pleasure in the remaining portion of the new year. You have been performing a brilliant job.

Lovely just what I was searching for.Thanks to the author for taking his clock time on this one.

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information. Your website is very useful. Thanks for sharing.

Video Marketing Explained And Why Every Business Should Use It

Very mice post, will share it on my social media network

I would like to thnkx for the efforts you have put in writing this blog. I am hoping the same high-grade blog post from you in the upcoming as well. In fact your creative writing abilities has inspired me to get my own blog now. Really the blogging is spreading its wings quickly. Your write up is a good example of it.

I am glad to be one of many visitants on this great internet site (:, thanks for posting.

It’s hard to find knowledgeable people on this topic, but you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

Backlinks generator software helping you to generate over 12 million backlinks for any link in minutes. Easy to operate and provide you with full report of all created backlinks. Ideal for personal use or start your own online business.

Some genuinely nice and utilitarian information on this website , as well I conceive the style and design holds good features.

Hey this is great article. I will certainly personally recommend to my friends. I’m confident they will be benefited from this website.

Really Appreciate this post, is there any way I can get an email sent to me when you make a new update?

Great write-up, I?¦m normal visitor of one?¦s site, maintain up the nice operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a long time.

It’s in point of fact a nice and helpful piece of info. I am happy that you just shared this useful info with us. Please stay us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

You have mentioned very interesting points! ps nice website .

I likewise conceive therefore, perfectly pent post! .

Nice post. I learn something more challenging on different blogs everyday. It will always be stimulating to read content from other writers and practice a little something from their store. I’d prefer to use some with the content on my blog whether you don’t mind. Natually I’ll give you a link on your web blog. Thanks for sharing.

Thank you for every other informative blog. Where else could I get that type of information written in such an ideal manner? I have a mission that I am just now working on, and I have been at the look out for such info.

F*ckin’ tremendous things here. I’m very happy to see your article. Thank you a lot and i am looking ahead to contact you. Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?

Good day very nice blog!! Man .. Beautiful .. Superb .. I’ll bookmark your website and take the feeds also?KI’m happy to search out so many helpful information right here within the publish, we want develop more strategies on this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

I am glad to be a visitor of this unadulterated web blog! , thanks for this rare information! .

I got what you mean ,bookmarked, very nice site.

Simply want to say your article is as astounding. The clearness in your post is simply cool and i can assume you’re an expert on this subject. Fine with your permission allow me to grab your feed to keep up to date with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please carry on the enjoyable work.

I just couldn’t go away your website before suggesting that I actually enjoyed the usual info a person supply in your guests? Is going to be again continuously to inspect new posts

obviously like your web-site however you have to check the spelling on quite a few of your posts. Several of them are rife with spelling problems and I in finding it very bothersome to tell the truth then again I will certainly come back again.

That is really fascinating, You are an overly skilled blogger. I’ve joined your rss feed and look forward to looking for more of your wonderful post. Also, I’ve shared your website in my social networks!

Приемник ЛИРА РП-248-1 – это радиоприемник коротких волн, который был разработан в СССР в 1980-х годах и до сих пор находит свое применение в различных сферах, включая морскую и авиационную навигацию, геодезию и другие области.

Outstanding post, you mentioned some great points in this article. Nice writing skills. Thank you!

I absolutely love your blog and find most of your post’s to be exactly I’m looking for. Would you offer guest writers to write content available for you? I wouldn’t mind composing a post or elaborating on a few of the subjects you write regarding here. Again, awesome weblog!

Probably one of the best articles i have read in long long time. Enjoyed it. Thank you for such nice post.

Спасибо за информацию о том, как создать эффективное объявление на доске для продажи автомобиля.

I like that the website has a responsive support team that addresses any issues or concerns promptly.

Definitely a magnificent site and revealing posts, I surely will bookmark your website.Best Regards!

Some very interesting points made in this post. Glad i found it. Thanks for sharing such valuable information.

My brother recommended I might like this web site. He was totally right. This post actually made my day. You cann’t imagine just how much time I had spent for this info! Thanks!

Incredible points made in this article. Outstanding arguments. Keep up the great work. LOVE your writing skills

Я хотел бы поблагодарить автора этой статьи за его основательное исследование и глубокий анализ. Он представил информацию с обширной перспективой и помог мне увидеть рассматриваемую тему с новой стороны. Очень впечатляюще!

Автор старается предоставить объективную картину, оставляя читателям возможность самостоятельно сформировать свое мнение.

CandyMail.org is an innovative platform that provides users with a secure and anonymous way to send and receive electronic mail. With the increasing concern over online privacy and data security, CandyMail.org has emerged as a reliable solution for individuals seeking confidentiality in their email communications. In this article, we will explore the unique features and benefits of CandyMail.org, as well as its impact on protecting user privacy.

Definitely a magnificent site and revealing posts, I surely will bookmark your website.Best Regards!

Я благодарен автору этой статьи за его способность представить сложные концепции в доступной форме. Он использовал ясный и простой язык, что помогло мне легко усвоить материал. Большое спасибо за такое понятное изложение!

Because the admin of this site is working,

no hesitation very quickly it will be well-known, due to its

feature contents.

I was suggested this website by my cousin. I am no longer sure whether or

not this post is written by means of him as no one else understand such

specific approximately my trouble. You’re wonderful!

Thanks!

Some really nice stuff on this website , I love it.

I must thank you for the efforts you’ve put in writing this blog.

I am hoping to check out the same high-grade blog posts from

you later on as well. In truth, your creative writing abilities has encouraged me to get

my very own site now 😉

It’s hard to find educated people for this subject,

however, you sound like you know what you’re talking about!

Thanks

Bitcoin Cash – die Kryptowährung für Ihr Unternehmen https://bchpls.org/

Terrific work! This is the type of info that should be shared

around the net. Disgrace on Google for no longer positioning this submit upper!

Come on over and talk over with my web site . Thank you =)

Welche Bitcoin Cash Geldbörsen sind empfehlenswert? https://bchpls.org/welche-bitcoin-cash-geldboersen-sind-empfehlenswert/

Wie profitiere ich von SmartBCH / DeFi? https://bchpls.org/wie-profitiere-ich-von-smartbch-defi/

Sie können Bitcoin Cash auf allen bekannten Handelsplattformen für Kryptowährungen kaufen und verkaufen. https://bchpls.org/

Ist Bitcoin Cash sicher? https://bchpls.org/ist-bitcoin-cash-sicher/

Akzeptieren Sie Bitcoin Cash noch heute! https://bchpls.org/akzeptieren-sie-bitcoin-cash-noch-heute/

https://ns2.electroncash.info

What’s up, its fastidious piece of writing on the topic of media print, we all understand

media is a wonderful source of data.

Hello friends, its enormous paragraph about educationand completely defined, keep it up all the

time.

Why is Bitcoin Cash a good investment? https://bchforeveryone.net/why-is-bitcoin-cash-a-good-investment/

This piece of writing is in fact a fastidious one

it assists new net people, who are wishing for blogging.

I am regular reader, how are you everybody? This article posted

at this web page is really nice.

Amazing issues here. I’m very satisfied to look

your post. Thank you so much and I am having a look ahead to touch

you. Will you please drop me a e-mail?

I believe this is one of the such a lot important

info for me. And i’m glad studying your article.

However should observation on few common things, The

web site style is wonderful, the articles is really

nice : D. Just right process, cheers

Thanks a lot for sharing this with all of us you really know what you are talking approximately!

Bookmarked. Please also talk over with my website =). We may have a hyperlink alternate arrangement among

us

Its like you learn my mind! You seem to understand so much approximately this, like you wrote the book in it or something.

I feel that you could do with some % to drive the message house a bit, but instead of that,

this is magnificent blog. An excellent read.

I will definitely be back.

Trotz Impfung: Warum gerade mehr Menschen an Corona sterben als letztes Jahr https://linkdirectory.at/de/detail/trotz-impfung-warum-gerade-mehr-menschen-an-corona-sterben-als-letztes-jahr

These are truly wonderful ideas in about blogging.

You have touched some fastidious things here. Any way

keep up wrinting.

Its like you read my mind! You seem to know a lot about this, like you wrote the book in it or something.

I think that you can do with a few pics to drive the message home a little bit, but instead of that,

this is excellent blog. A great read. I will certainly be back.

Hey There. I found your weblog using msn. This is a very well

written article. I’ll be sure to bookmark it and come back to learn extra of your

useful information. Thanks for the post. I will certainly return.

Wow, this paragraph is pleasant, my sister is analyzing such things,

thus I am going to let know her.

In our summaries, we place all the info from ahead of into a few brief

paragraphs.

Server resources for Bitcoin Cash – https://wiki.electroncash.de/wiki/Server_resources

I have read so many articles or reviews on the topic of the blogger lovers but this article is truly a good piece of writing, keep it up.

Durch Bitcoin Cash Akzeptanz kann Ihr Unternehmen zusätzliche Reichweite und Medienaufmerksamkeit bekommen. https://bchpls.org/

Sie können Bitcoin Cash auf allen bekannten Handelsplattformen für Kryptowährungen kaufen und verkaufen. https://bchpls.org/

Ist Bitcoin Cash sicher? https://bchpls.org/ist-bitcoin-cash-sicher/

What a material of un-ambiguity and preserveness of valuable experience on the topic of unpredicted emotions.

Ist Bitcoin Cash sicher? https://bchpls.org/ist-bitcoin-cash-sicher/

It’s truly a great and helpful piece of information. I’m happy that you shared this helpful info with us.

Please stay us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

Good day! Do you know if they make any plugins to protect against

hackers? I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any tips?

I am truly pleased to read this blog posts which consists of lots of useful data, thanks for providing these kinds of

statistics.

What’s up, always i used to check website posts here in the

early hours in the break of day, as i love to gain knowledge of more and more.

Wo kann ich Bitcoin Cash kaufen? https://bchpls.org/wo-kann-ich-bitcoin-cash-kaufen/

Bitcoin Cash – die Kryptowährung für Ihr Unternehmen https://bchpls.org/

This is a topic that is near to my heart… Many thanks!

Where are your contact details though?

This is very interesting, You’re a very skilled blogger.

I have joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of

your magnificent post. Also, I’ve shared your site in my social networks!

Keep on writing, great job!

Simply want to say your article is as astounding.

The clarity on your post is simply spectacular and i can assume you are an expert in this subject.

Well along with your permission allow me to take hold of your feed to keep updated with imminent post.

Thank you one million and please keep up the gratifying work.

Автор предоставляет разнообразные источники для более глубокого изучения темы.

Автор предлагает читателю разные взгляды на проблему, что способствует формированию собственного мнения.

Автор представляет аргументы разных сторон и помогает читателю получить объективное представление о проблеме.

I truly appreciate this post. I?¦ve been looking all over for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You have made my day! Thank you again

► 1. Amazon Echo Studio – https://amzn.to/3vrjClP

Hảy cho tôi biết pin cả hai dùng thực tế bao nhiêu giờ

Satochip – Hardware solutions to help you manage your cryptocurrency https://linkdirectory.at/detail/satochip-hardware-solutions-to-help-you-manage-your-cryptocurrency

Buy the Satochip Hardware Wallet to manage your cryptocurrency securely https://satochip.io/

Satochip — Hardware wallet on smart card (USB/NFC) https://medium.com/@georg.engelmann/satochip-hardware-wallet-on-smart-card-usb-nfc-b3456557f6ec

With havin so much content do you ever run into any problems of plagorism or copyright infringement? My website has a lot of completely unique content I’ve either authored myself or outsourced but it seems a lot of it is popping it up all over the internet without my authorization. Do you know any ways to help stop content from being ripped off? I’d truly appreciate it.

It’s an awesome paragraph in support of all the internet visitors; they will take benefit from it I am sure.

Bitcoin Cash: A Vision of Financial Freedom and Inclusivity https://bchgang.net/

Welche Bitcoin Cash Geldbörsen sind empfehlenswert? https://bchpls.org/welche-bitcoin-cash-geldboersen-sind-empfehlenswert/

Live Gold Prices, Gold News, and Analysis: Mining News – Kitco provides real-time updates on gold prices, along with news and analysis related to the mining industry. https://linkdirectory.at/detail/live-gold-prices-gold-news-and-analysis-mining-news-kitco

Pretty section of content. I just stumbled upon your website and in accession capital to assert that I acquire actually enjoyed account your

blog posts. Any way I will be subscribing to

your feeds and even I achievement you access consistently quickly.

https://events.electroncash.net

This was followed by a nice and extensive chat with her, a really enjoyable and stimulating conversation with fantastic pictures and videos.

Hi Guys! New cam models, looking to meet new and interesting people.

Excellent, what a web site it is! This website gives valuable data to us, keep it up.

I am genuinely amazed with your profound understanding and superb writing style. The knowledge you share is evident in every piece you write. It’s obvious that you put a lot of effort into researching your topics, and that effort is well-appreciated. We appreciate your efforts in sharing this valuable knowledge. Continue the excellent job! https://www.elevenviral.com

I’m thoroughly captivated with your deep insights and stellar writing style. Your expertise shines through in every sentence. It’s evident that you invest a great deal of effort into understanding your topics, and this effort is well-appreciated. Thank you for sharing such valuable insights. Continue the excellent job! https://www.elevenviral.com

I appreciate the effort you put into creating this content. Keep it up!

I am genuinely amazed with your keen analysis and superb ability to convey information. Your depth of knowledge shines through in every piece you write. It’s evident that you invest a great deal of effort into understanding your topics, and that effort does not go unnoticed. Thank you for sharing such valuable insights. Keep up the great work! https://www.elevenviral.com

Thank you for sharing your expertise. Your insights are truly valuable.

I am genuinely amazed by the keen analysis and stellar way of expressing complex ideas. Your depth of knowledge shines through in every sentence. It’s evident that you spend considerable time into researching your topics, and the results is well-appreciated. Thanks for providing such detailed information. Keep on enlightening us! https://www.elevenviral.com

I am genuinely amazed by the profound understanding and superb ability to convey information. Your expertise is evident in every sentence. It’s obvious that you put a lot of effort into delving into your topics, and the results pays off. Thank you for sharing such detailed information. Keep up the great work! https://www.elevenviral.com

I am genuinely amazed with your profound understanding and superb way of expressing complex ideas. Your depth of knowledge clearly stands out in each paragraph. It’s obvious that you put a lot of effort into understanding your topics, and that effort does not go unnoticed. We appreciate your efforts in sharing such detailed information. Keep up the great work! https://www.elevenviral.com

I’m thoroughly captivated by the profound understanding and excellent ability to convey information. Your expertise shines through in every sentence. It’s evident that you put a lot of effort into understanding your topics, and that effort pays off. Thanks for providing this valuable knowledge. Continue the excellent job! http://www.RochelleMaize.com

I’m thoroughly captivated with your profound understanding and stellar ability to convey information. Your expertise shines through in every sentence. It’s obvious that you spend considerable time into understanding your topics, and that effort pays off. Thanks for providing this valuable knowledge. Keep up the great work! http://www.RochelleMaize.com

I’m thoroughly captivated by the profound understanding and superb writing style. Your depth of knowledge clearly stands out in every piece you write. It’s obvious that you invest a great deal of effort into delving into your topics, and this effort pays off. Thank you for sharing such valuable insights. Keep up the great work! https://rochellemaize.com

Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe: achat kamagra – pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique

Pharmacie Internationale en ligne https://kamagraenligne.shop/# pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es

Статья представляет аккуратный обзор современных исследований и различных точек зрения на данную проблему. Она предоставляет хороший стартовый пункт для тех, кто хочет изучить тему более подробно.

Автор старается оставаться нейтральным, позволяя читателям сами сформировать свое мнение на основе представленной информации.

Автор старается не высказывать собственного мнения, что способствует нейтральному освещению темы.

Статья содержит анализ преимуществ и недостатков различных решений, связанных с темой.

Автор представляет сложные темы в понятной и доступной форме для широкой аудитории.

Мне понравилась четкая и логическая структура статьи, которая облегчает чтение.

Мне понравилось разнообразие и глубина исследований, представленных в статье.

Я хотел бы выразить признательность автору этой статьи за его объективный подход к теме. Он представил разные точки зрения и аргументы, что позволило мне получить полное представление о рассматриваемой проблеме. Очень впечатляюще!

Статья содержит информацию, подкрепленную фактами и исследованиями.

In today’s fast-paced world, staying informed about the latest developments both locally and globally is more crucial than ever. With a plethora of news outlets struggling for attention, it’s important to find a reliable source that provides not just news, but perspectives, and stories that matter to you. This is where [url=https://www.usatoday.com/]USAtoday.com [/url], a top online news agency in the USA, stands out. Our dedication to delivering the most current news about the USA and the world makes us a primary resource for readers who seek to stay ahead of the curve.

Subscribe for Exclusive Content: By subscribing to USAtoday.com, you gain access to exclusive content, newsletters, and updates that keep you ahead of the news cycle.

[url=https://www.usatoday.com/]USAtoday.com [/url] is not just a news website; it’s a dynamic platform that strengthens its readers through timely, accurate, and comprehensive reporting. As we navigate through an ever-changing landscape, our mission remains unwavering: to keep you informed, engaged, and connected. Subscribe to us today and become part of a community that values quality journalism and informed citizenship.

Hi there just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The words in your content seem to be running off the screen in Firefox. I’m not sure if this is a formatting issue or something to do with web browser compatibility but I thought I’d post to let you know. The design and style look great though! Hope you get the problem fixed soon. Thanks

Я прочитал эту статью с большим удовольствием! Автор умело смешал факты и личные наблюдения, что придало ей уникальный характер. Я узнал много интересного и наслаждался каждым абзацем. Браво!

Hey there! I’m at work browsing your blog from my new iphone 4! Just wanted to say I love reading through your blog and look forward to all your posts! Carry on the excellent work!

Thanks for the auspicious writeup. It actually was a entertainment account it. Glance complex to more introduced agreeable from you! By the way, how could we keep up a correspondence?

Я прочитал эту статью с большим удовольствием! Автор умело смешал факты и личные наблюдения, что придало ей уникальный характер. Я узнал много интересного и наслаждался каждым абзацем. Браво!

Я хотел бы выразить свою благодарность автору этой статьи за исчерпывающую информацию, которую он предоставил. Я нашел ответы на многие свои вопросы и получил новые знания. Это действительно ценный ресурс!

Hi there, You have done a fantastic job. I’ll certainly digg it and personally recommend to my friends. I am confident they’ll be benefited from this web site.

These are actually fantastic ideas in concerning blogging. You have touched some fastidious things here. Any way keep up wrinting.

I know this website gives quality dependent posts and additional information, is there any other site which presents these stuff in quality?

Автор предлагает анализ преимуществ и недостатков разных подходов к решению проблемы.

Статья позволяет получить общую картину по данной теме.

Thanks for a marvelous posting! I really enjoyed reading it, you might be a great author. I will ensure that I bookmark your blog and definitely will come back at some point. I want to encourage yourself to continue your great writing, have a nice evening!

Автор статьи предоставляет сбалансированную информацию, основанную на проверенных источниках.

Автор предлагает аргументы, подкрепленные проверенными источниками.

Автор статьи представляет различные точки зрения и факты, не выражая собственных суждений.

Статья представляет информацию в обобщенной форме, предоставляя ключевые факты и статистику.

Очень хорошо исследованная статья! Она содержит много подробностей и является надежным источником информации. Я оцениваю автора за его тщательную работу и приветствую его старания в предоставлении читателям качественного контента.

Hi there would you mind stating which blog platform you’re using? I’m planning to start my own blog soon but I’m having a hard time choosing between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal. The reason I ask is because your design seems different then most blogs and I’m looking for something unique. P.S Apologies for getting off-topic but I had to ask!

My relatives all the time say that I am killing my time here at web, except I know I am getting know-how everyday by reading such pleasant content.

You’ve made some decent points there. I looked on the internet for additional information about the issue and found most individuals will go along with your views on this website.

Отлично, что автор обратил внимание на разные точки зрения и представил их в сбалансированном виде.

I got this website from my friend who shared with me regarding this web site and now this time I am visiting this web site and reading very informative articles or reviews at this time.

Автор старается дать читателям достаточно информации для их собственного исследования и принятия решений.

Эта статья – настоящий кладезь информации! Я оцениваю ее полноту и разнообразие представленных фактов. Автор сделал тщательное исследование и предоставил нам ценный ресурс для изучения темы. Большое спасибо за такое ценное содержание!

Я хотел бы подчеркнуть четкость и последовательность изложения в этой статье. Автор сумел объединить информацию в понятный и логичный рассказ, что помогло мне лучше усвоить материал. Очень ценная статья!

Хорошая статья, в которой автор предлагает различные точки зрения и аргументы.

Автор статьи предоставляет информацию, подкрепленную надежными источниками, что делает ее достоверной и нейтральной.

Hi there, i read your blog occasionally and i own a similar one and i was just curious if you get a lot of spam feedback? If so how do you reduce it, any plugin or anything you can recommend? I get so much lately it’s driving me crazy so any support is very much appreciated.

Simply want to say your article is as amazing. The clarity in your post is simply great and i can assume you’re an expert on this subject. Well with your permission let me to grab your feed to keep updated with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please keep up the enjoyable work.

Автор хорошо подготовился к теме и представил разнообразные факты.

Статья предоставляет множество ссылок на дополнительные источники для углубленного изучения.

It’s genuinely very complex in this busy life to listen news on Television, therefore I only use the web for that purpose, and obtain the newest news.

Интересная статья, содержит много информации.

After I initially commented I seem to have clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and from now on each time a comment is added I recieve four emails with the exact same comment. There has to be a way you can remove me from that service? Appreciate it!

Автор статьи представляет различные точки зрения и факты, не выражая собственных суждений.

I am truly thankful to the owner of this web site who has shared this fantastic piece of writing at at this place.

Это позволяет читателям получить разностороннюю информацию и самостоятельно сделать выводы.

Hi, I do believe this is a great web site. I stumbledupon it 😉 I may revisit yet again since I bookmarked it. Money and freedom is the greatest way to change, may you be rich and continue to guide other people.

Greetings! Very useful advice in this particular article! It is the little changes that make the most significant changes. Many thanks for sharing!

That is a really good tip especially to those fresh to the blogosphere. Simple but very accurate info… Thanks for sharing this one. A must read post!

Мне понравился баланс между фактами и мнениями в статье.

Мне понравилась аргументация автора, основанная на логической цепочке рассуждений.

Hi, all is going nicely here and ofcourse every one is sharing information, that’s genuinely good, keep up writing.

Полезная информация для тех, кто стремится получить всестороннее представление.

Aw, this was an incredibly nice post. Finding the time and actual effort to make a top notch article… but what can I say… I hesitate a whole lot and never manage to get anything done.

Очень интересная исследовательская работа! Статья содержит актуальные факты, аргументированные доказательствами. Это отличный источник информации для всех, кто хочет поглубже изучить данную тему.

This is a good tip particularly to those fresh to the blogosphere. Short but very precise info… Appreciate your sharing this one. A must read article!