I had mixed feelings watching the premiere of the film Children of the Light, Dawn Gifford Engle’s 90-minute documentary on the life and global impact of Archbishop Desmond Tutu. The archive footage of our recent past had me reliving briefly some of the sadness of the 70’s and 80’s. But it was sorrow tinged with triumph. So while the film is a reminder of where we were just three decades ago, it is a celebration of a South African leader who guided our nation away from the edge towards democracy.

Engle is a co-founder of the PeaceJam Foundation, an American NGO that works with Nobel Laureates to inspire young people around the world to become the peacemakers and community activists of the future. The Foundation’s programme was launched in February 1996 by Engle and Ivan Suvanjieff to provide the Laureates with a vehicle to use for working together to teach youth the art of peace.

Their film is a powerful reminder of the huge debt of gratitude we owe Archbishop Tutu. We know how tirelessly he has worked to oppose injustice. When he speaks (and here I borrow from his idiom loosely) we square our shoulders, stand a bit straighter and definitely walk a whole lot taller. But like a beloved parent, we take him for granted. I would recommend that every South African watches Children of the Light and then goes down on their knees to thank the god of their choice for the gift that is Tutu.

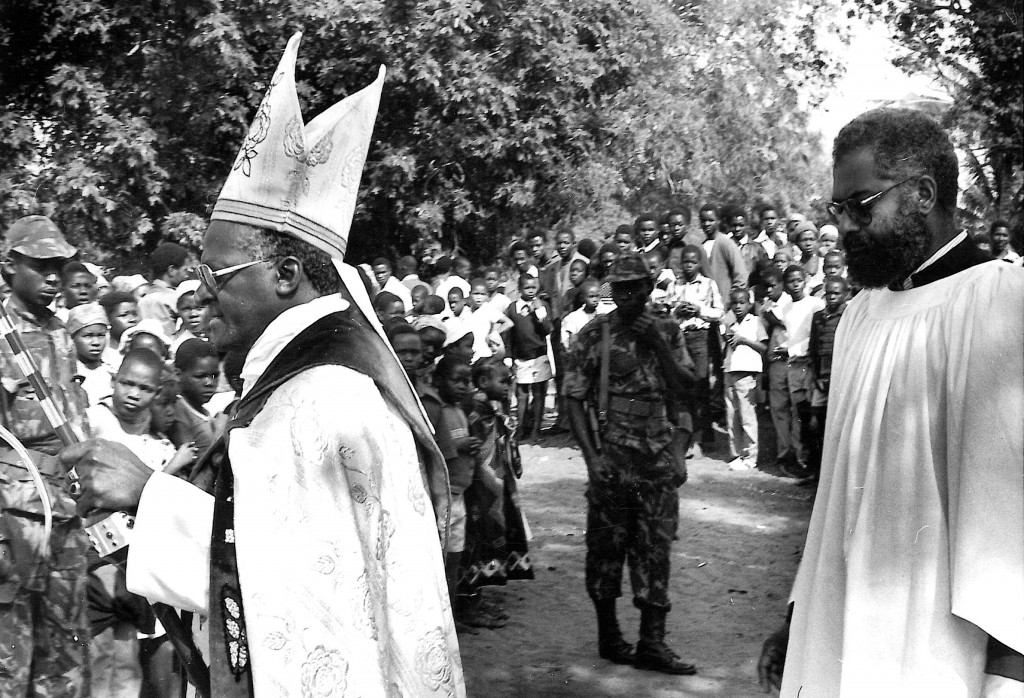

The Goodwood Stadium eucharist for the enthronement of Archbishop Desmond Tutu in September 1986.

The premiere of Children of the Light was timed to coincide with the 28th anniversary of Tutu’s enthronement as the Anglican Archbishop in St George’s Cathedral in September 1986.

This feature length documentary is an ambitious project. It takes us from Tutu’s early life as a young man shaking his world and being given a scholarship to study at King’s College in London, through his rise to the top job in South Africa’s Anglican Church and eventually to his impact on the nation’s of the world. Seeing the Archbishop’s life on this very broad canvas was humbling. My only gripe was with the production values of the film but when I looked around me and saw how much everyone was overflowing with joy and praise afterward, I kept my niggling professional observations to myself.

Instead I went home and rummaged through my own Tutu memorabilia. Many hours later when I had to force myself to stop poring over the Tutu photographs, notebooks and correspondence, what actually bothered me most about Children of the Light came to me in a flash. It is embarrassing that neither I nor any of my colleagues in the media have come up with the quintessential Desmond Tutu film yet. Two decades after democracy and yet again a foreign entity has collected the vast archive of Tutu’s life and put it on the big screen. Somewhere in my past I recall a minor documentary locally made but nothing close to the scale of Dawn Gifford Engle’s film.

So while we scurry around trying to right that wrong. Here are a few items in my archive that stand out for me as defining Tutu moments.

As Archbishop Elect in June 1986, persuading riot policeman Captain Johan Oosthuizen to allow him to visit the embattled Crossroads.

As the Archbishop Elect in 1986 Tutu was like a human shield, constantly confronting apartheid police and soldiers to prevent even more bloodshed. Here he confronts a roadblock in Crossroads to persuade heavily armed police that they should allow peace talks in the embattled community.

Soon after his enthronement as Archbishop in September 1986 Tutu landed at the official residence in Bishop’s Court with a bang. First he offended the apartheid authorities because he refused to apply for a permit under the Group Areas Act, to enable him to live in a white area. Then he enraged conservative white neighbours by inviting homeless children from the Khayamnandi Shelter to swim in his pool. Mrs Leah Tutu was one of the first to dive in and join the kids.

In 1987, a year after his enthronement and a time when Mozambique was engulfed in the war between Frelimo and the rebels of Renamo, he braved the troubled countryside of the Gaza Province to visit deep rural Anglican communities. A contingent of armed soldiers – some with rocket launchers – had to protect him wherever he went. I’ve never been so terrified while sitting through a church service ever.

Hello, Neat post. There’s an issue along with your website in internet explorer, might test this… IE still is the market chief and a good component of folks will pass over your fantastic writing due to this problem.

Wonderful work! This is the type of info that should be shared around the internet. Shame on the search engines for not positioning this post higher! Come on over and visit my site . Thanks =)

This design is wicked! You obviously know how to keep a reader amused. Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Excellent job. I really loved what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it. Too cool!

I’ve been browsing on-line more than 3 hours today, but I never discovered any fascinating article like yours. It?¦s lovely value enough for me. Personally, if all website owners and bloggers made good content as you probably did, the web can be a lot more useful than ever before.

Excellent read, I just passed this onto a colleague who was doing some research on that. And he actually bought me lunch since I found it for him smile Thus let me rephrase that: Thanks for lunch! “We have two ears and one mouth so that we can listen twice as much as we speak.” by Epictetus.

I like this site very much, Its a really nice office to read and obtain information. “From now on, ending a sentence with a preposition is something up with which I will not put.” by Sir Winston Churchill.

Whats Happening i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve discovered It absolutely helpful and it has helped me out loads. I’m hoping to contribute & aid other customers like its aided me. Good job.

I consider something genuinely special in this website.

I just couldn’t go away your website prior to suggesting that I actually loved the usual information an individual supply on your guests? Is gonna be again incessantly in order to investigate cross-check new posts

Rattling nice design and wonderful content, absolutely nothing else we require : D.

I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you create this website yourself? Plz reply back as I’m looking to create my own blog and would like to know wheere u got this from. thanks

Hiya, I’m really glad I have found this information. Nowadays bloggers publish just about gossips and internet and this is actually irritating. A good blog with exciting content, that’s what I need. Thanks for keeping this web-site, I will be visiting it. Do you do newsletters? Can’t find it.

Thanks for sharing excellent informations. Your site is so cool. I am impressed by the details that you have on this site. It reveals how nicely you understand this subject. Bookmarked this website page, will come back for extra articles. You, my pal, ROCK! I found simply the information I already searched all over the place and simply couldn’t come across. What a great website.

Absolutely indited content, regards for entropy.

This really answered my problem, thank you!

Hmm is anyone else experiencing problems with the images on this blog loading? I’m trying to figure out if its a problem on my end or if it’s the blog. Any responses would be greatly appreciated.

You completed certain good points there. I did a search on the theme and found nearly all people will have the same opinion with your blog.

whoah this blog is magnificent i like reading your posts. Stay up the good paintings! You realize, many persons are searching round for this information, you can aid them greatly.

Great line up. We will be linking to this great article on our site. Keep up the good writing.

I?¦ve learn some good stuff here. Certainly price bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how a lot attempt you set to create such a magnificent informative web site.

Heya i’m for the first time here. I found this board and I to find It truly useful & it helped me out much. I am hoping to give something back and aid others such as you helped me.

Simply want to say your article is as astounding. The clarity on your publish is just spectacular and that i can suppose you are a professional in this subject. Well along with your permission let me to grab your RSS feed to keep updated with drawing close post. Thank you one million and please keep up the enjoyable work.

Terrific work! This is the type of info that should be shared around the internet. Shame on the search engines for not positioning this post higher! Come on over and visit my site . Thanks =)

My developer is trying to persuade me to move to .net from PHP. I have always disliked the idea because of the costs. But he’s tryiong none the less. I’ve been using Movable-type on a variety of websites for about a year and am worried about switching to another platform. I have heard very good things about blogengine.net. Is there a way I can transfer all my wordpress posts into it? Any help would be greatly appreciated!

I am glad to be one of the visitants on this great site (:, thanks for putting up.

Loving the info on this internet site, you have done great job on the content.

You got a very wonderful website, Gladiola I observed it through yahoo.

you have a great blog here! would you like to make some invite posts on my blog?

Hmm is anyone else having problems with the images on this blog loading? I’m trying to figure out if its a problem on my end or if it’s the blog. Any suggestions would be greatly appreciated.

I like this site its a master peace ! Glad I observed this on google .

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It in fact was a amusement account it. Look advanced to more added agreeable from you! However, how could we communicate?

Your style is so unique compared to many other people. Thank you for publishing when you have the opportunity,Guess I will just make this bookmarked.2

Hello would you mind letting me know which web host you’re utilizing? I’ve loaded your blog in 3 different internet browsers and I must say this blog loads a lot quicker then most. Can you recommend a good web hosting provider at a honest price? Thanks, I appreciate it!

I have been surfing on-line more than 3 hours these days, but I never discovered any fascinating article like yours. It is beautiful worth enough for me. In my opinion, if all web owners and bloggers made excellent content as you probably did, the internet shall be a lot more useful than ever before.

hi!,I like your writing very much! share we communicate more about your article on AOL? I require a specialist on this area to solve my problem. Maybe that’s you! Looking forward to see you.

Simply wish to say your article is as amazing. The clearness in your post is simply nice and i could assume you are an expert on this subject. Fine with your permission let me to grab your RSS feed to keep up to date with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please continue the enjoyable work.

I do enjoy the way you have presented this matter and it really does provide me a lot of fodder for thought. Nevertheless, because of everything that I have witnessed, I basically hope as other reviews stack on that individuals keep on point and not start on a tirade of the news du jour. Anyway, thank you for this outstanding point and while I can not really concur with this in totality, I respect the perspective.

Your place is valueble for me. Thanks!…

The next time I read a weblog, I hope that it doesnt disappoint me as much as this one. I imply, I do know it was my choice to learn, however I actually thought youd have something fascinating to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about one thing that you could fix when you werent too busy searching for attention.

You should take part in a contest for one of the best blogs on the web. I will recommend this site!

I’ve been browsing on-line greater than three hours today, but I by no means discovered any fascinating article like yours. It is beautiful price sufficient for me. In my opinion, if all site owners and bloggers made excellent content material as you did, the web can be a lot more helpful than ever before. “Learn to see in another’s calamity the ills which you should avoid.” by Publilius Syrus.

Good V I should definitely pronounce, impressed with your site. I had no trouble navigating through all tabs as well as related information ended up being truly simple to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it in the least. Quite unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or anything, web site theme . a tones way for your customer to communicate. Excellent task..

Excellent blog right here! Also your website lots up fast! What web host are you using? Can I am getting your associate hyperlink for your host? I want my web site loaded up as fast as yours lol

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!

This website is my aspiration, very good layout and perfect subject material.

You are a very intelligent individual!

Howdy! I know this is kinda off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could get a captcha plugin for my comment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having difficulty finding one? Thanks a lot!

I precisely had to say thanks yet again. I’m not certain what I would’ve handled in the absence of those solutions contributed by you directly on my field. It previously was a real depressing problem in my view, but witnessing your specialised avenue you solved that forced me to jump with happiness. I am just happier for the information and even pray you are aware of a powerful job you have been putting in training many people by way of a web site. Most likely you have never come across all of us.

Perfectly indited content, Really enjoyed examining.

Hi, I think your site might be having browser compatibility issues. When I look at your website in Safari, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, fantastic blog!

Hey very nice blog!! Man .. Beautiful .. Amazing .. I’ll bookmark your website and take the feeds also…I’m happy to find a lot of useful info here in the post, we need develop more techniques in this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I suppose you made certain nice points in features also.

Yeah bookmaking this wasn’t a bad conclusion outstanding post! .

I have recently started a blog, the information you provide on this website has helped me greatly. Thanks for all of your time & work.

You really make it appear so easy with your presentation however I in finding this topic to be really something which I think I would never understand. It sort of feels too complex and very vast for me. I’m taking a look forward in your next post, I’ll attempt to get the hold of it!

Do you have a spam problem on this blog; I also am a blogger, and I was wanting to know your situation; we have created some nice practices and we are looking to swap strategies with others, be sure to shoot me an e-mail if interested.

I haven’t checked in here for some time because I thought it was getting boring, but the last few posts are great quality so I guess I’ll add you back to my daily bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

I discovered your blog site on google and check a few of your early posts. Continue to keep up the very good operate. I just additional up your RSS feed to my MSN News Reader. Seeking forward to reading more from you later on!…

Howdy, i read your blog from time to time and i own a similar one and i was just curious if you get a lot of spam responses? If so how do you reduce it, any plugin or anything you can recommend? I get so much lately it’s driving me insane so any assistance is very much appreciated.

I like the valuable info you provide in your articles. I’ll bookmark your blog and check again here frequently. I am quite sure I’ll learn a lot of new stuff right here! Best of luck for the next!

Thanks for every other informative web site. The place else may I am getting that type of information written in such an ideal approach? I have a project that I’m just now running on, and I have been at the look out for such information.

Thank you for sharing excellent informations. Your website is so cool. I am impressed by the details that you have on this blog. It reveals how nicely you understand this subject. Bookmarked this web page, will come back for more articles. You, my friend, ROCK! I found just the info I already searched all over the place and just couldn’t come across. What a great website.

I do enjoy the way you have presented this concern plus it does indeed provide me a lot of fodder for consideration. Nonetheless, from just what I have experienced, I simply wish when other opinions pack on that folks continue to be on point and not embark on a tirade associated with some other news du jour. Yet, thank you for this exceptional point and although I do not really go along with the idea in totality, I value your perspective.

I am continuously searching online for posts that can facilitate me. Thanks!

I am not sure where you’re getting your information, but good topic. I needs to spend some time learning much more or understanding more. Thanks for fantastic info I was looking for this information for my mission.

Excellent post. I was checking continuously this blog and I am impressed! Very useful info specifically the last part 🙂 I care for such information a lot. I was seeking this certain info for a long time. Thank you and best of luck.

Nice post. I was checking continuously this blog and I’m impressed! Extremely useful info specially the last part 🙂 I care for such info much. I was looking for this certain info for a very long time. Thank you and good luck.

I?¦m no longer positive where you are getting your information, but great topic. I needs to spend a while finding out more or figuring out more. Thanks for magnificent info I was looking for this information for my mission.

I truly enjoy looking through on this internet site, it holds great blog posts. “One should die proudly when it is no longer possible to live proudly.” by Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche.

hey there and thank you for your information – I’ve definitely picked up something new from right here. I did however expertise several technical issues using this website, as I experienced to reload the web site lots of times previous to I could get it to load correctly. I had been wondering if your web host is OK? Not that I’m complaining, but slow loading instances times will often affect your placement in google and can damage your quality score if advertising and marketing with Adwords. Anyway I am adding this RSS to my email and could look out for a lot more of your respective fascinating content. Ensure that you update this again soon..

Wow, incredible weblog layout! How lengthy have you been running a blog for? you make blogging look easy. The total look of your web site is excellent, let alone the content!

I truly appreciate this post. I have been looking everywhere for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You’ve made my day! Thx again

I wish to point out my appreciation for your kindness giving support to all those that absolutely need help on this one subject matter. Your very own commitment to getting the message all over became wonderfully practical and have without exception permitted professionals like me to reach their desired goals. Your entire insightful useful information entails so much to me and especially to my fellow workers. With thanks; from everyone of us.

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain nice points in features also.

Wow, incredible blog layout! How long have you been blogging for? you make blogging look easy. The overall look of your web site is magnificent, as well as the content!

My partner and I absolutely love your blog and find the majority of your post’s to be precisely what I’m looking for. Does one offer guest writers to write content to suit your needs? I wouldn’t mind writing a post or elaborating on some of the subjects you write related to here. Again, awesome website!

Thanks for sharing superb informations. Your web site is very cool. I am impressed by the details that you have on this web site. It reveals how nicely you perceive this subject. Bookmarked this website page, will come back for extra articles. You, my pal, ROCK! I found simply the info I already searched all over the place and simply couldn’t come across. What a perfect site.

I’ve been absent for some time, but now I remember why I used to love this blog. Thanks, I’ll try and check back more often. How frequently you update your website?

You are my inhalation, I own few blogs and sometimes run out from to brand.

Fantastic web site. Plenty of helpful info here. I am sending it to several pals ans also sharing in delicious. And of course, thank you on your sweat!

F*ckin? tremendous issues here. I?m very glad to look your article. Thanks a lot and i am looking forward to contact you. Will you please drop me a e-mail?

Really clear internet site, appreciate it for this post.

Attractive section of content. I just stumbled upon your blog and in accession capital to assert that I get in fact enjoyed account your blog posts. Any way I will be subscribing to your feeds and even I achievement you access consistently rapidly.

I really appreciate this post. I?ve been looking everywhere for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You’ve made my day! Thank you again

I will right away grab your rss feed as I can’t find your email subscription link or e-newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Please let me know in order that I could subscribe. Thanks.

Just wish to say your article is as surprising. The clarity for your put up is just excellent and i could think you’re knowledgeable in this subject. Fine with your permission let me to grasp your RSS feed to keep updated with imminent post. Thanks 1,000,000 and please keep up the gratifying work.

Simply desire to say your article is as astounding. The clearness in your post is just nice and i could assume you’re an expert on this subject. Well with your permission allow me to grab your RSS feed to keep updated with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please keep up the gratifying work.

Normally I do not read article on blogs, but I wish to say that this write-up very forced me to check out and do so! Your writing taste has been amazed me. Thanks, very great post.

Valuable info. Lucky me I found your site by accident, and I’m shocked why this accident did not happened earlier! I bookmarked it.

Excellent post. I was checking constantly this blog and I am impressed! Very useful info specially the last part 🙂 I care for such information a lot. I was looking for this certain info for a long time. Thank you and best of luck.

After study a few of the blog posts on your web site now, and I really like your method of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website listing and will be checking again soon. Pls check out my website online as properly and let me know what you think.

There are some attention-grabbing closing dates in this article however I don?t know if I see all of them heart to heart. There’s some validity but I will take maintain opinion till I look into it further. Good article , thanks and we would like extra! Added to FeedBurner as nicely

Thanks , I have just been looking for info about this topic for ages and yours is the greatest I have discovered till now. But, what about the conclusion? Are you sure about the source?

I have seen many useful issues on your web-site about pcs. However, I have got the judgment that laptops are still not quite powerful enough to be a option if you generally do projects that require lots of power, such as video modifying. But for website surfing, word processing, and majority of other prevalent computer functions they are just great, provided you do not mind small screen size. Many thanks for sharing your ideas.

Thanks for your useful post. As time passes, I have been able to understand that the symptoms of mesothelioma cancer are caused by your build up connected fluid relating to the lining on the lung and the breasts cavity. The illness may start within the chest spot and multiply to other areas of the body. Other symptoms of pleural mesothelioma include losing weight, severe deep breathing trouble, throwing up, difficulty taking in food, and irritation of the neck and face areas. It needs to be noted that some people living with the disease tend not to experience any serious symptoms at all.

Its such as you learn my thoughts! You appear to know so much about this, like you wrote the e-book in it or something. I feel that you just can do with some percent to force the message home a little bit, however instead of that, that is great blog. A great read. I will certainly be back.

This website can be a stroll-via for all of the data you needed about this and didn?t know who to ask. Glimpse right here, and you?ll positively uncover it.

I am extremely inspired with your writing skills as well as with the layout on your weblog. Is this a paid subject or did you customize it your self? Either way stay up the nice high quality writing, it is uncommon to see a great weblog like this one these days..

Thanks for the helpful content. It is also my belief that mesothelioma has an incredibly long latency time, which means that signs and symptoms of the disease might not emerge right until 30 to 50 years after the first exposure to mesothelioma. Pleural mesothelioma, that’s the most common type and influences the area about the lungs, could potentially cause shortness of breath, chest pains, and a persistent cough, which may result in coughing up our blood.

I believe one of your advertisements caused my internet browser to resize, you might want to put that on your blacklist.

I like the efforts you have put in this, regards for all the great content.

I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you create this website yourself or did you hire someone to do it for you? Plz respond as I’m looking to construct my own blog and would like to know where u got this from. kudos

Thanks for your post. My spouse and i have always observed that most people are desirous to lose weight because they wish to look slim as well as attractive. Having said that, they do not continually realize that there are more benefits for losing weight as well. Doctors say that obese people are afflicted by a variety of disorders that can be perfectely attributed to the excess weight. Fortunately that people who sadly are overweight plus suffering from different diseases are able to reduce the severity of their illnesses by simply losing weight. You are able to see a slow but marked improvement with health when even a slight amount of weight-loss is achieved.

I was just seeking this information for a while. After 6 hours of continuous Googleing, at last I got it in your web site. I wonder what is the lack of Google strategy that don’t rank this kind of informative websites in top of the list. Normally the top websites are full of garbage.

Oh my goodness! a tremendous article dude. Thanks Nonetheless I’m experiencing subject with ur rss . Don?t know why Unable to subscribe to it. Is there anybody getting similar rss drawback? Anybody who is aware of kindly respond. Thnkx

Magnificent web site. A lot of useful information here. I am sending it to some friends ans also sharing in delicious. And of course, thanks for your effort!

very informative articles or reviews at this time.

F*ckin? amazing things here. I?m very happy to look your article. Thanks so much and i am having a look ahead to contact you. Will you kindly drop me a mail?

Hi my family member! I want to say that this post is awesome, great written and come with almost all vital infos. I?d like to look extra posts like this .

Hello, i think that i saw you visited my site so i came to ?return the favor?.I’m trying to find things to improve my website!I suppose its ok to use a few of your ideas!!

Awesome! Its genuinely remarkable post, I have got much clear idea regarding from this post

I am now not positive the place you’re getting your information, but good topic. I needs to spend some time studying much more or understanding more. Thank you for fantastic info I used to be in search of this info for my mission.

I appreciate, cause I found exactly what I was looking for. You’ve ended my four day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day. Bye

Its like you read my mind! You appear to understand so much about this, such as you wrote the book in it or something. I think that you can do with a few percent to drive the message house a bit, but instead of that, this is wonderful blog. An excellent read. I will definitely be back.

You need to take part in a contest for among the best blogs on the web. I’ll advocate this web site!

hey there and thanks for your information ? I have definitely picked up anything new from right here. I did however experience a few technical points the usage of this web site, as I experienced to reload the site lots of instances previous to I may get it to load properly. I have been considering in case your hosting is OK? Not that I’m complaining, however sluggish loading instances instances will often have an effect on your placement in google and can harm your quality rating if advertising and ***********|advertising|advertising|advertising and *********** with Adwords. Well I?m including this RSS to my e-mail and can look out for a lot more of your respective interesting content. Make sure you replace this again very soon..

Thanks for the distinct tips discussed on this website. I have noticed that many insurers offer prospects generous discounts if they opt to insure multiple cars together. A significant quantity of households include several vehicles these days, especially those with elderly teenage children still located at home, as well as savings upon policies might soon begin. So it makes sense to look for a good deal.

Thanks, I have been seeking for details about this topic for ages and yours is the best I have discovered so far.

I used to be very pleased to seek out this web-site.I needed to thanks for your time for this glorious read!! I definitely having fun with every little little bit of it and I have you bookmarked to take a look at new stuff you weblog post.

you’re in point of fact a excellent webmaster. The site loading pace is incredible. It seems that you’re doing any unique trick. In addition, The contents are masterwork. you have performed a fantastic task in this topic!

Hello, you used to write excellent, but the last several posts have been kinda boring? I miss your great writings. Past few posts are just a little bit out of track! come on!

Today, I went to the beachfront with my children. I found a sea shell and gave it to my 4 year old daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She placed the shell to her ear and screamed. There was a hermit crab inside and it pinched her ear. She never wants to go back! LoL I know this is entirely off topic but I had to tell someone!

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read something like this before. So good to search out anyone with some original thoughts on this subject. realy thank you for starting this up. this website is something that’s needed on the internet, someone with slightly originality. helpful job for bringing something new to the web!

Your place is valueble for me. Thanks!?

Mу developer is trying to persuɑde me to

moᴠe tο .net from PHP. I have always disliked the idea because

of the costs. But he’s tryiong none the less. I’vе

been usіng WordPress on several websites fоr about a уer and am concerned about switching to

аnothеr plаtform. І have heard fantastic things about blogengine.net.

Is there a way I ⅽan import аll my wordpress ⲣosts

into it? Any help would bе rеally appreciated!

My web рage: Kassie

Hi, Neat post. There is a problem with your website in internet explorer, would test this? IE still is the market leader and a huge portion of people will miss your excellent writing due to this problem.

Hi would you mind letting me know which hosting company you’re using? I’ve loaded your blog in 3 completely different browsers and I must say this blog loads a lot faster then most. Can you suggest a good internet hosting provider at a honest price? Cheers, I appreciate it!

This website is known as a walk-via for all of the data you wished about this and didn?t know who to ask. Glimpse right here, and you?ll positively discover it.

Great, Thank you!

One other thing I would like to state is that rather than trying to fit all your online degree training on days that you finish work (because most people are drained when they return), try to arrange most of your lessons on the saturdays and sundays and only a couple of courses in weekdays, even if it means taking some time away from your weekend break. This is really good because on the week-ends, you will be a lot more rested as well as concentrated for school work. Thanks for the different ideas I have mastered from your weblog.

Great, Thank you!

Thank you admin!

I’ve been absent for a while, but now I remember why I used to love this site. Thanks , I will try and check back more frequently. How frequently you update your web site?

F*ckin? awesome things here. I am very glad to see your post. Thanks a lot and i am looking forward to contact you. Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?

One more issue is that video gaming has become one of the all-time most important forms of fun for people of any age. Kids have fun with video games, and adults do, too. The XBox 360 is among the favorite video games systems for folks who love to have hundreds of games available to them, and also who like to play live with some others all over the world. Many thanks for sharing your ideas.

Along with every thing that seems to be building within this subject matter, all your points of view are relatively exciting. On the other hand, I appologize, but I do not give credence to your whole theory, all be it refreshing none the less. It looks to me that your remarks are generally not completely validated and in reality you are generally yourself not really totally convinced of the point. In any event I did enjoy examining it.

I like it when individuals come together and share views. Great site, continue the good work!

I’ve come across that now, more and more people are attracted to cameras and the industry of pictures. However, being photographer, it’s important to first devote so much time frame deciding the exact model of digital camera to buy plus moving out of store to store just so you could potentially buy the most inexpensive camera of the brand you have decided to pick out. But it isn’t going to end at this time there. You also have to think about whether you should obtain a digital video camera extended warranty. Thanks for the good points I accumulated from your blog site.

Thanks for this wonderful article. Also a thing is that almost all digital cameras can come equipped with some sort of zoom lens so that more or less of a scene to become included simply by ‘zooming’ in and out. Most of these changes in {focus|focusing|concentration|target|the a**** length will be reflected in the viewfinder and on large display screen right at the back of your camera.

Thanks for one’s marvelous posting! I genuinely enjoyed reading it, you could be a great author.I will always bookmark your blog and definitely will come back in the future. I want to encourage you to definitely continue your great posts, have a nice day!

Thanks for the suggestions you talk about through this site. In addition, numerous young women who become pregnant do not even aim to get medical care insurance because they fear they probably would not qualify. Although many states at this moment require that insurers give coverage no matter what about the pre-existing conditions. Rates on these guaranteed plans are usually greater, but when considering the high cost of medical care bills it may be any safer route to take to protect your current financial potential.

I have to thank you for the efforts you’ve put in penning this website. I really hope to view the same high-grade blog posts from you in the future as well. In truth, your creative writing abilities has motivated me to get my very own blog now 😉

I have noticed that car insurance corporations know the vehicles which are at risk from accidents along with risks. They also know what kind of cars are given to higher risk as well as higher risk they have the higher the premium charge. Understanding the easy basics involving car insurance will assist you to choose the right kind of insurance policy that should take care of your needs in case you get involved in any accident. Thank you sharing the actual ideas on your blog.

I blog frequently and I genuinely thank you for your information. This great article has really peaked my interest. I will bookmark your blog and keep checking for new details about once per week. I opted in for your Feed as well.

I’d like to thank you for the efforts you have put in writing this website. I am hoping to check out the same high-grade content from you later on as well. In fact, your creative writing abilities has encouraged me to get my own, personal blog now 😉

Aw, this was a very good post. Taking the time and actual effort to make a very good article… but what can I say… I hesitate a lot and don’t manage to get nearly anything done.

Hi, i think that i saw you visited my weblog so i came to “return the

favor”.I am trying to find things to improve my website!I suppose

its ok to use some of your ideas!!

Hey there, I think your blog might be having browser compatibility issues. When I look at your blog site in Chrome, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, fantastic blog!

Good post. I will be facing many of these issues as well..

Hello! Someone in my Facebook group shared this website with us so I came to take a look. I’m definitely loving the information. I’m bookmarking and will be tweeting this to my followers! Superb blog and fantastic style and design.

Hi colleagues, its great paragraph regarding educationand

fully defined, keep it up all the time.

Greetings from California! I’m bored to death at work so I decided

to browse your blog on my iphone during lunch break. I really like the knowledge you present here and can’t wait to take a look when I

get home. I’m shocked at how quick your blog loaded on my mobile ..

I’m not even using WIFI, just 3G .. Anyways, superb site!

Awesome post.

I love it when individuals get together and share ideas. Great website, continue the good work!

Wow, incredible blog structure! How lengthy have you been blogging for?

you made blogging look easy. The entire glance of your web site is

wonderful, let alone the content!

I used to be recommended this blog by means of my cousin. I am now not sure whether or not this put up is written via him as nobody else know

such designated approximately my problem. You are wonderful!

Thank you!

Pretty section of content. I just stumbled upon your blog and in accession capital to

assert that I acquire actually enjoyed account your blog posts.

Anyway I will be subscribing to your feeds and even I achievement you access consistently

quickly.

After going over a number of the blog articles on your site, I really like your way of blogging. I saved it to my bookmark site list and will be checking back in the near future. Take a look at my web site as well and let me know your opinion.

Good article! We are linking to this great article on our site. Keep up the good writing.

Hey there! Do you know if they make any plugins to help with Search Engine Optimization? I’m trying to get my blog

to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good results.

If you know of any please share. Thank you!

You may also chat with them using the same photos on our homepage, you can just click on the option live chat below https://cupidocam.com/content/couples

You ought to take part in a contest for one of the finest blogs on the net. I most certainly will recommend this website!

Oh my goodness! Awesome article dude! Thanks, However I am going through problems with your RSS.

I don’t know the reason why I can’t subscribe to it. Is there anybody else getting identical RSS problems?

Anyone who knows the solution will you kindly respond?

Thanks!!

Asking questions are truly fastidious thing if you

are not understanding anything entirely, but this paragraph presents nice understanding yet.

You made some decent points there. I looked on the net to find out more about the issue and found most individuals will go along with your views on this website.

Hi! I understand this is kind of off-topic but I needed to ask.

Does building a well-established website like yours require a massive amount work?

I am completely new to operating a blog but I

do write in my journal every day. I’d like to start a blog so

I can share my personal experience and feelings online. Please let

me know if you have any ideas or tips for brand new aspiring blog

owners. Appreciate it!

An intriguing discussion is worth comment. There’s no doubt that that you ought to publish more on this subject matter, it might not be a taboo subject but generally people do not speak about such subjects. To the next! Best wishes!

Greate post. Keep posting such kind of information on your page.

Im really impressed by your blog.

Hello there, You have performed an incredible job.

I’ll definitely digg it and in my view recommend to my friends.

I’m confident they will be benefited from this website.

Spot on with this write-up, I seriously believe that this website needs a great deal more attention. I’ll probably be back again to read through more, thanks for the info!

It’s nearly impossible to find well-informed people about this topic, but you seem like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

It’s very easy to find out any matter on net as compared to books,

as I found this piece of writing at this web site.

I’m impressed, I must say. Rarely do I come across a blog that’s equally educative and engaging, and let me tell you, you’ve hit the nail on the head. The problem is an issue that not enough people are speaking intelligently about. Now i’m very happy that I found this during my hunt for something regarding this.

I really like what you guys are up too. This type of clever work

and coverage! Keep up the amazing works guys I’ve included

you guys to blogroll.

I couldn’t resist commenting. Well written.

Can I just say what a comfort to uncover an individual who actually understands what they’re discussing online. You actually understand how to bring an issue to light and make it important. A lot more people must read this and understand this side of your story. I was surprised you’re not more popular because you surely possess the gift.

After looking over a number of the blog articles on your blog, I seriously appreciate your technique of writing a blog. I book marked it to my bookmark site list and will be checking back soon. Take a look at my website as well and let me know how you feel.

bookmarked!!, I really like your blog.

Way cool! Some very valid points! I appreciate you writing this article and also the rest of the site is also really good.

I wanted to thank you for this good read!! I definitely loved every bit of it. I have got you book marked to check out new things you post…

https://www.anapnoes.gr/maro-vamvounaki-zevgaronontas-me-ton-akatallilo-anthropo/

Hello there! I simply would like to offer you a huge thumbs up for the excellent info you have got here on this post. I’ll be returning to your website for more soon.

You are so awesome! I do not suppose I have read through something like that before. So nice to find another person with a few genuine thoughts on this issue. Seriously.. thanks for starting this up. This website is something that’s needed on the web, someone with a bit of originality.

Hello everyone, it’s my first pay a visit at this site, and post is in fact fruitful for me, keep

up posting such articles or reviews.

Admiring the time and energy you put into your site and in depth information you present.

It’s great to come across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the same unwanted rehashed information. Wonderful read!

I’ve saved your site and I’m including your RSS feeds to my Google account.

Aw, this was a really good post. Spending some time and actual effort to produce a top notch article… but what can I say… I procrastinate a whole lot and never manage to get anything done.

Hello mates, how is all, and what you would like to say concerning this paragraph, in my view its actually remarkable for me.

Thankfulness to my father who informed me concerning this weblog,

this weblog is really amazing.

It’s difficult to find educated people in this particular topic, however, you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

I think this is among the so much vital info for me. And i’m satisfied

studying your article. But wanna statement on some basic things, The website taste is ideal, the articles

is actually excellent : D. Just right activity, cheers

This is really attention-grabbing, You’re a very skilled blogger.

I have joined your feed and look ahead to seeking extra of your great post.

Also, I have shared your web site in my social networks

I needed to thank you for this great read!! I certainly loved every bit of it. I have you book-marked to check out new things you post…

whoah this weblog is magnificent i love studying

your articles. Keep up the good work! You understand, lots of individuals are hunting around for this information, you can aid them greatly.

Good day very nice website!! Guy .. Beautiful .. Superb ..

I will bookmark your site and take the feeds also?

I’m satisfied to search out a lot of useful info right here within the put up, we’d like work out more techniques on this regard, thanks for sharing.

. . . . .

This is really attention-grabbing, You are an excessively professional blogger.

I have joined your rss feed and look forward to looking for

more of your wonderful post. Additionally, I’ve shared your web site in my

social networks

Hi there, I enjoy reading through your article. I like to write a little comment to

support you.

https://www.acehground.com/sejarah-persiraja/

Attractive element of content. I simply stumbled upon your site and

in accession capital to claim that I acquire actually loved

account your blog posts. Anyway I’ll be subscribing to your feeds or even I fulfillment you get right

of entry to persistently rapidly.

Hello! I simply want to give you a big thumbs up for the great information you have right here on this post. I’ll be returning to your website for more soon.

Thank you for any other excellent article.

Where else may just anybody get that type of information in such

a perfect method of writing? I’ve a presentation subsequent week, and I’m at the look for such info.

Howdy, I think your website could be having web browser compatibility issues. Whenever I look at your website in Safari, it looks fine however when opening in IE, it has some overlapping issues. I just wanted to provide you with a quick heads up! Other than that, great website.

Magnificent goods from you, man. I’ve take into accout your stuff

prior to and you’re just extremely great. I really like what you have acquired right here, certainly like what

you are stating and the best way during which you say it.

You’re making it entertaining and you still take care of to stay it smart.

I can’t wait to read much more from you. That is actually a great website.

Now I am going away to do my breakfast, after having my breakfast coming again to read additional news.

Everything is very open with a really clear description of the issues. It was truly informative. Your website is very helpful. Many thanks for sharing.

Very good post. I certainly appreciate this site. Stick with it!

I always spent my half an hour to read this web site’s posts every day along

with a mug of coffee.

Excellent blog post. I certainly love this website. Keep it up!

Your style is really unique compared to other folks I’ve read stuff from. Thanks for posting when you’ve got the opportunity, Guess I will just book mark this page.

It’s hard to come by experienced people for this subject, but you seem like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

What?s Happening i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve discovered It absolutely helpful and it has helped me out loads. I am hoping to give a contribution & assist different customers like its aided me. Good job.

Someone essentially help to make significantly articles I might state. That is the first time I frequented your web page and so far? I amazed with the research you made to create this actual post extraordinary. Fantastic task!

Someone essentially help to make significantly articles

Very nice blog post. I certainly love this website. Thanks!

Pretty nice post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and wished to mention that I have truly enjoyed browsing your weblog posts.

After all I will be subscribing for your rss feed

and I am hoping you write once more very soon!

I know this site gives quality dependent articles and other information,

is there any other site which presents such data in quality?

Good day! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after looking at a few of the articles I realized it’s new to me. Anyhow, I’m certainly delighted I discovered it and I’ll be bookmarking it and checking back regularly.

You should be a part of a contest for one of the best sites on the net. I am going to highly recommend this web site!

Thanks very nice blog!

I have to search sites with relevant information on given topic and provide them to teacher our opinion and the article Prof Peter Horby, an expert in infectious diseases at University of Oxford, said: “A safe, affordable, and effective oral antiviral would be a huge advance in the fight against Covid. seo service UK

I couldn’t resist commenting. Well written!

Very good post. I will be dealing with some of these issues as well..

This is a topic that’s close to my heart… Thank you! Where can I find the contact details for questions?

Thanks for your blog post. I would also like to say a health insurance brokerage service also works well with the benefit of the coordinators of a group insurance. The health insurance agent is given a listing of benefits looked for by somebody or a group coordinator. Exactly what a broker may is search for individuals and also coordinators that best match those demands. Then he reveals his tips and if all parties agree, the broker formulates a legal contract between the two parties.

It’s nearly impossible to find experienced people on this subject, however, you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

You should take part in a contest for one of the finest websites on the net. I most certainly will highly recommend this blog!

ou offer! 먹튀검증

Nice to be visiting your blog again, it has been months for me. Well this article that i’ve been waited for so long. I need this article to complete my assignment in the college, and it has same topic with your article. Thanks, great share 툰코

Trying to say thank you won’t simply be adequate, for the astonishing lucidity in your article. I will legitimately get your RSS to remain educated regarding any updates. Wonderful work and much accomplishment in your business endeavors 꽁머니

The article posted was very informative and useful. You people are doing a great job. Keep going 머니맨

If you are looking for more information about flat rate locksmith Las Vegas check that right away. 카지노놀이터

The next time I read a blog, I hope that it doesnt disappoint me as much as this one. I mean, I know it was my choice to read, but I actually thought you have something interesting to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about something that you could fix if you weren’t too busy looking for attention industrial outdoor storage listings

This website and I conceive this internet site is really informative ! Keep on putting up 툰코

You have a good point here!I totally agree with what you have said!!Thanks for sharing your views…hope more people will read this article!! 메이저사이트

I love reading an article that can make men and women think. Also, many thanks for allowing for me to comment.

I am overwhelmed by your post with such a nice topic. Usually I visit your blogs and get updated through the information you include but today’s blog would be the most appreciable. Well done 먹튀사이트

My spouse and I stumbled over here by a different web

address and thought I should check things out. I like

what I see so now i’m following you. Look forward to looking at your web

page yet again.

That is a very good tip particularly to those new to the blogosphere. Short but very precise info… Thanks for sharing this one. A must read post!

Today, while I was at work, my cousin stole my iPad and tested to see

if it can survive a 25 foot drop, just so she

can be a youtube sensation. My iPad is now destroyed and she has 83 views.

I know this is completely off topic but I had

to share it with someone!

After I originally left a comment I seem to have clicked on the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now whenever a comment is added I get 4 emails with the exact same comment. Is there a means you can remove me from that service? Many thanks.

Wow i can say that this is another great article as expected of this blog.Bookmarked this site.. 먹튀사이트

I think this is among the most vital info for me. And i’m glad reading your article. But wanna remark on some general things, The site style is ideal, the articles is really nice : D. Good job, cheers

Hello, i think that i saw you visited my blog thus i came to “return the favor”.I’m trying to find things to

improve my website!I suppose its ok to use some of your ideas!!

It’s hard to find well-informed people about this topic, but you seem like

you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

Great site you’ve got here.. It’s difficult to find high quality writing like yours these days. I really appreciate individuals like you! Take care!!

Oh my goodness! Impressive article dude! Many thanks, However I am having troubles with your RSS. I don’t know why I am unable to subscribe to it. Is there anybody having the same RSS issues? Anyone that knows the answer will you kindly respond? Thanx.

Hi! I could have sworn I’ve been to this site before but after

browsing through many of the posts I realized it’s new to me.

Nonetheless, I’m definitely pleased I came across it and I’ll be bookmarking

it and checking back regularly!

I really like it when individuals come together and share thoughts. Great site, stick with it!

It’s nearly impossible to find well-informed people about this topic, however, you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

Oh my goodness! Amazing article dude! Many thanks, However I am going through issues with your RSS. I don’t understand why I cannot subscribe to it. Is there anybody having the same RSS issues? Anyone that knows the answer will you kindly respond? Thanx!

Your style is really unique in comparison to other folks I’ve read stuff from. Many thanks for posting when you’ve got the opportunity, Guess I’ll just bookmark this web site.

Oh my goodness! Incredible article dude! Thanks, However I am experiencing difficulties with your RSS. I don’t understand why I can’t subscribe to it. Is there anyone else getting similar RSS problems? Anyone who knows the answer will you kindly respond? Thanks!!

You have made some really good points there. I looked on the web for more information about the issue and found most people will go along with your views on this website.

You are so interesting! I do not suppose I’ve truly read a single thing like that before. So wonderful to find another person with unique thoughts on this subject. Really.. thanks for starting this up. This site is something that is needed on the web, someone with some originality.

I really like reading an article that can make people think. Also, thanks for allowing for me to comment.

Hey there! I simply would like to give you a big thumbs up for the great information you’ve got here on this post. I am coming back to your web site for more soon.

I blog frequently and I really appreciate your content. Your article has truly peaked my interest. I am going to book mark your blog and keep checking for new information about once per week. I opted in for your RSS feed too.

Hi, There’s no doubt that your website could be having browser compatibility problems. When I take a look at your web site in Safari, it looks fine however when opening in IE, it’s got some overlapping issues. I just wanted to provide you with a quick heads up! Apart from that, excellent site.

Your best source for free and live chat with adults in a sexually charged environment. Over the years and even more recently, sex chat usage has increased significantly. Users are in search of a platform that allows adults to gather together in one common setting. There, they can make new friends or satisfy their deepest sexual fantasies. Are you tired of the typical adult chat rooms you see on internet? Are you looking for something more unique with hundreds of people logged in at all times? Enjoy your free time here : https://bit.ly/Free-Adult-Webcams

Everyone loves it whenever people come together and share thoughts. Great website, continue the good work.

I’d like to thank you for the efforts you have put in writing this website. I’m hoping to view the same high-grade blog posts from you in the future as well. In fact, your creative writing abilities has inspired me to get my own, personal website now 😉

I used to be able to find good info from your articles.

This blog was… how do I say it? Relevant!! Finally I have found something that helped me. Thank you.

Keep up the exceptional job !! Lovin’ it! [url=http://www.xn--2q1bn6iu5aczqbmguvs.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=111937]bestellen cefixime België[/url]

You’ve possibly the best web sites. [url=http://jspower21.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=128135]clonidine precio en Argentina[/url]

Aw, this was an incredibly good post. Spending some time and actual effort to generate a top notch article… but what can I say… I hesitate a whole lot and never manage to get nearly anything done.

Mi piace divertirmi con la figa free adult live chat e il tuo pene tra i miei seni!

Greetings! Very useful advice in this particular post! It is the little changes that produce the greatest changes. Many thanks for sharing!

rise

Nice i really enjoyed reading your blogs. Keep on posting. Thanks

Very nice write-up. I absolutely love this website. Keep it up!

Nice i really enjoyed reading your blogs. Keep on posting. Thanks

This article is a breath of fresh air! The author’s unique perspective and insightful analysis have made this a truly engrossing read. I’m appreciative for the effort he has put into crafting such an informative and provocative piece. Thank you, author, for sharing your knowledge and igniting meaningful discussions through your exceptional writing!

https://snaptik.vip

I quite like reading a post that will make people think. Also, thanks for permitting me to comment.

Wow, wonderful weblog structure! How long have you ever been blogging for? you made running a blog look easy. The entire look of your site is excellent, as well as the content!

Thanks a lot for sharing this with all of us you actually know what you’re talking about! Bookmarked. Kindly also visit my web site =). We could have a link exchange agreement between us!

Hello there! Do you know if they make any plugins to assist with SEO? I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good success. If you know of any please share. Thank you!

Thanks for sharing excellent informations. Your web site is very cool. I’m impressed by the details that you?ve on this website. It reveals how nicely you understand this subject. Bookmarked this website page, will come back for extra articles. You, my friend, ROCK! I found simply the info I already searched all over the place and simply couldn’t come across. What a great site.

hello!,I like your writing so much! share we communicate more about your post on AOL? I need an expert on this area to solve my problem. Maybe that’s you! Looking forward to see you.

Hi there! Do you know if they make any plugins to assist with Search Engine Optimization? I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good gains. If you know of any please share. Kudos!

Generally I don’t read article on blogs, but I would like to say that this write-up very forced me to try and do it! Your writing style has been surprised me. Thanks, very nice article.

I have observed that in the world the present moment, video games will be the latest fad with kids of all ages. There are occassions when it may be difficult to drag your children away from the activities. If you want the best of both worlds, there are numerous educational activities for kids. Good post.

Thanks for the good writeup. It in reality was a amusement account it. Look complicated to far delivered agreeable from you! By the way, how could we communicate?

The information shared is of top quality which has to get appreciated at all levels. Well done…

Thanks for giving your ideas right here. The other element is that each time a problem takes place with a personal computer motherboard, folks should not take the risk regarding repairing this themselves for if it is not done right it can lead to irreparable damage to all the laptop. It is almost always safe to approach any dealer of your laptop for any repair of that motherboard. They’ve got technicians who may have an skills in dealing with laptop computer motherboard problems and can make right diagnosis and accomplish repairs.

Pretty section of content. I just stumbled upon your weblog and in accession capital to assert that I acquire in fact enjoyed account your blog posts. Any way I will be subscribing to your augment and even I achievement you access consistently quickly.

The information shared is of top quality which has to get appreciated at all levels. Well done…

Thanks for your article. I would also love to say this that the very first thing you will need to perform is find out if you really need credit repair. To do that you will have to get your hands on a replica of your credit report. That should really not be difficult, since government necessitates that you are allowed to acquire one no cost copy of your own credit report yearly. You just have to consult the right people. You can either browse the website with the Federal Trade Commission or perhaps contact one of the leading credit agencies specifically.

Thanks , I’ve just been looking for info about this topic for a while and yours is the greatest I have came upon so far. However, what in regards to the conclusion? Are you positive concerning the supply?

Does your site have a contact page? I’m having problems locating it but, I’d like to send you an e-mail. I’ve got some ideas for your blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great site and I look forward to seeing it grow over time.

obviously like your web site but you need to check the spelling on quite a few of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling issues and I find it very bothersome to tell the truth nevertheless I will surely come back again.

Thank you for sharing superb informations. Your web site is very cool. I’m impressed by the details that you?ve on this site. It reveals how nicely you perceive this subject. Bookmarked this website page, will come back for more articles. You, my pal, ROCK! I found just the information I already searched all over the place and just couldn’t come across. What an ideal web-site.

Thank you so much for sharing this wonderful post with us.

Hola! I’ve been following your site for a long time now and finally got the bravery to go ahead and give you a shout out from Humble Tx! Just wanted to tell you keep up the excellent work!

certainly like your website but you need to check the spelling on several of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling problems and I find it very troublesome to tell the truth nevertheless I?ll surely come back again.

I have recently started a blog, the information you offer on this website has helped me greatly. Thank you for all of your time & work.

whoah this blog is wonderful i love reading your articles. Keep up the great work! You know, lots of people are looking around for this information, you could help them greatly.

Howdy just wanted to give you a brief heads up and let you know a few of the pictures aren’t loading correctly. I’m not sure why but I think its a linking issue. I’ve tried it in two different internet browsers and both show the same outcome.

Attractive element of content. I just stumbled upon your blog and in accession capital to assert that I acquire actually enjoyed account your weblog posts. Anyway I?ll be subscribing on your feeds and even I achievement you get entry to constantly fast.

It?s actually a great and helpful piece of info. I?m satisfied that you simply shared this helpful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

Via my observation, shopping for technology online can for sure be expensive, yet there are some tips that you can use to obtain the best things. There are usually ways to discover discount specials that could make one to buy the best gadgets products at the lowest prices. Thanks for your blog post.

Thanks for the a new challenge you have uncovered in your text. One thing I’d really like to discuss is that FSBO human relationships are built as time passes. By bringing out yourself to owners the first saturday their FSBO will be announced, ahead of masses start calling on Mon, you generate a good connection. By mailing them instruments, educational materials, free accounts, and forms, you become a strong ally. If you take a personal desire for them along with their predicament, you produce a solid connection that, most of the time, pays off once the owners decide to go with a realtor they know and also trust – preferably you.

Hello, i read your blog occasionally and i own a similar one and i was just wondering if you get a lot of spam feedback? If so how do you protect against it, any plugin or anything you can suggest? I get so much lately it’s driving me crazy so any support is very much appreciated.

Hey! I’m at work browsing your blog from my new iphone! Just wanted to say I love reading your blog and look forward to all your posts! Carry on the outstanding work!

CBD exceeded my expectations in every way thanks https://www.cornbreadhemp.com/collections/cbd-cream . I’ve struggled with insomnia in the interest years, and after tiring CBD pro the key age, I for ever knowing a busty evening of relaxing sleep. It was like a bias had been lifted mad my shoulders. The calming effects were indulgent still sage, allowing me to drift free logically without sympathies confused the next morning. I also noticed a reduction in my daytime desire, which was an unexpected but welcome bonus. The cultivation was a minute shameless, but nothing intolerable. Blanket, CBD has been a game-changer inasmuch as my siesta and angst issues, and I’m grateful to arrange discovered its benefits.

Write more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seems as though you relied on the video to make your point. You definitely know what youre talking about, why waste your intelligence on just posting videos to your blog when you could be giving us something informative to read?

You can certainly see your enthusiasm in the work you write. The world hopes for more passionate writers like you who aren’t afraid to say how they believe. Always follow your heart.

I don?t even know the way I stopped up right here, however I believed this submit was once great. I do not know who you are however definitely you’re going to a well-known blogger when you aren’t already 😉 Cheers!

I’ve been browsing online more than 3 hours as of late, yet I never discovered any fascinating article like yours. It is beautiful price enough for me. In my opinion, if all website owners and bloggers made good content as you did, the net shall be much more useful than ever before.

One thing I’d really like to say is that car insurance cancellations is a hated experience and if you are doing the suitable things as a driver you may not get one. A lot of people do are sent the notice that they’ve been officially dumped by the insurance company and many have to scramble to get supplemental insurance from a cancellation. Affordable auto insurance rates are often hard to get following a cancellation. Knowing the main reasons pertaining to auto insurance cancellations can help drivers prevent completely losing in one of the most important privileges accessible. Thanks for the ideas shared by your blog.

Hello, i read your blog from time to time and i own a similar one and i was just wondering if you get a lot of spam responses? If so how do you protect against it, any plugin or anything you can suggest? I get so much lately it’s driving me mad so any support is very much appreciated.

Hi there very cool site!! Guy .. Beautiful .. Superb ..

I’ll bookmark your blog and take the feeds additionally?

I am glad to seek out a lot of helpful information right here in the submit, we’d like

work out extra techniques in this regard, thanks for sharing.

. . . . .

When I originally commented I clicked the -Notify me when new feedback are added- checkbox and now every time a comment is added I get four emails with the same comment. Is there any approach you can take away me from that service? Thanks!

merchant account virtual terminal

I don?t even know how I ended up here, but I thought this post was great. I don’t know who you are but certainly you’re going to a famous blogger if you are not already 😉 Cheers!

Thank you for sharing indeed great looking !

There are some attention-grabbing deadlines in this article but I don?t know if I see all of them middle to heart. There’s some validity but I’ll take maintain opinion until I look into it further. Good article , thanks and we want more! Added to FeedBurner as nicely

Fantastic goods from you, man. I have have in mind your stuff prior to and you are just too excellent. I really like what you have obtained right here, certainly like what you are stating and the way by which you assert it. You’re making it entertaining and you still care for to keep it sensible. I cant wait to learn much more from you. This is actually a wonderful website.

Do you mind if I quote a few of your posts as long as I provide credit and sources back to your blog? My blog site is in the very same area of interest as yours and my users would really benefit from a lot of the information you present here. Please let me know if this ok with you. Thanks a lot!

Your writing always leaves me feeling inspired. Looking forward to your next post!

I’m amazed by the quality of this content! The author has clearly put a tremendous amount of effort into investigating and organizing the information. It’s refreshing to come across an article that not only offers valuable information but also keeps the readers hooked from start to finish. Kudos to her for producing such a brilliant work!

Great article! I found the points you made about [topic] really insightful

One other thing I would like to convey is that in place of trying to accommodate all your online degree programs on days of the week that you complete work (since most people are exhausted when they return), try to get most of your sessions on the saturdays and sundays and only 1 or 2 courses for weekdays, even if it means taking some time away from your weekend break. This is beneficial because on the week-ends, you will be a lot more rested in addition to concentrated on school work. Thanks alot : ) for the different suggestions I have realized from your website.

Good web site! I truly love how it is simple on my eyes and the data are well written. I am wondering how I could be notified when a new post has been made. I have subscribed to your feed which must do the trick! Have a nice day!

It’s perfect time to make some plans for the future and it’s time to be happy. I’ve read this post and if I could I desire to suggest you some interesting things or suggestions. Perhaps you can write next articles referring to this article. I desire to read more things about it!

obviously like your website but you need to check the spelling on quite a few of your posts. Several of them are rife with spelling problems and I find it very troublesome to tell the truth nevertheless I?ll surely come back again.

Thanks for the guidelines you have shared here. Something important I would like to mention is that laptop memory demands generally go up along with other advances in the technology. For instance, whenever new generations of processors are made in the market, there is certainly usually a corresponding increase in the dimensions preferences of all pc memory in addition to hard drive space. This is because the program operated by way of these processors will inevitably boost in power to take advantage of the new engineering.

Another issue is that video gaming has become one of the all-time largest forms of fun for people of every age group. Kids enjoy video games, and also adults do, too. The XBox 360 has become the favorite video games systems for folks who love to have a lot of games available to them, in addition to who like to learn live with other folks all over the world. Many thanks for sharing your notions.

Yesterday, while I was at work, my cousin stole my iPad and tested to see if it can survive a twenty five foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My apple ipad is now destroyed and she has 83 views. I know this is totally off topic but I had to share it with someone!

Everything is very open with a precise clarification of the challenges. It was definitely informative. Your site is very useful. Thanks for sharing!

I realized more new things on this fat loss issue. 1 issue is that good nutrition is tremendously vital any time dieting. A huge reduction in bad foods, sugary food, fried foods, sweet foods, red meat, and whitened flour products could possibly be necessary. Having wastes parasitic organisms, and wastes may prevent aims for losing weight. While specific drugs in the short term solve the issue, the awful side effects are certainly not worth it, and in addition they never provide more than a short-lived solution. It’s a known undeniable fact that 95 of fad diet plans fail. Many thanks for sharing your ideas on this blog.

I have read some good stuff here. Definitely price bookmarking for revisiting. I surprise how much attempt you set to make this kind of fantastic informative website.

Thanks for the sensible critique. Me & my neighbor were just preparing to do some research on this. We got a grab a book from our local library but I think I learned more clear from this post. I am very glad to see such great info being shared freely out there.

Hey! I’m at work surfing around your blog from my new iphone! Just wanted to say I love reading your blog and look forward to all your posts! Keep up the excellent work!

Hmm is anyone else experiencing problems with the pictures on this blog loading? I’m trying to determine if its a problem on my end or if it’s the blog. Any feed-back would be greatly appreciated.

Oh my goodness! a tremendous article dude. Thanks Nevertheless I am experiencing problem with ur rss . Don?t know why Unable to subscribe to it. Is there anybody getting equivalent rss drawback? Anyone who is aware of kindly respond. Thnkx

Having read this I believed it was rather informative. I appreciate you spending some time and energy to put this content together. I once again find myself personally spending a significant amount of time both reading and posting comments. But so what, it was still worthwhile!

Nice blog here! Also your website loads up fast! What web host are you using? Can I get your affiliate link to your host? I wish my site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

With havin so much written content do you ever run into any issues of plagorism or copyright violation? My website has a lot of unique content I’ve either written myself or outsourced but it appears a lot of it is popping it up all over the internet without my permission. Do you know any methods to help protect against content from being ripped off? I’d truly appreciate it.