This weekend marks the second anniversary of the tragedy that killed 34 people in 2012. Already people are calling August 16th Marikana Day. This shocking turning point in our history as well as the strike that lasted almost half a year, has turned our focus to the real cost of platinum mining.

A young couple bends over the glass in the mall’s exclusive jewellery store. The ring set they discuss with a slick assistant has no price tag but the plush hush in the shop is a loud indicator of luxury. Down in the platinum mines a junior worker will have to smash rocks for about half a year to earn this kind of money.

It’s easy to feel judgmental about people who buy R 75,000 rings. But most of the time workers are sweltering in 48 deg C, one kilometre underground, for something almost everyone needs. Each car on the road demands that about 100 tons of ore becomes the platinum for its catalytic converter, the auto part that turns harmful emissions into relatively harmless carbon dioxide.

The reverberations of Marikana 2012 should shake up communities way beyond the forlorn landscape of Rustenburg. The fallout from the tragedy should not only be rumbling in the empty hearts of widows, orphans, the jobless, the bereaved and the wounded. But we live in a world where we don’t question too harshly the privileges of the ‘platinum’ classes or the needs of car owners. In our unspoken hierarchy of priorities, mineworkers don’t occupy the top positions.

The Wonderkop Hill in Marikana, now another memorial to the fallen in the battle against social injustice.

Nobody Is Listening

“We say there needs to be change but nobody cares to listen,” says Chris Molebatsi a Marikana community activist and Monitor with the Bench Marks Foundation.

The Foundation was set up by the SA Council of Churches to ensure multinational corporations respect human rights. Their concern is that private corporations, often with the support of government leaders, make very large profits while communities suffer high levels of inequality and poverty. The Foundation is equally concerned with the destruction of our air, water and soil resources that results from mining. They conduct research and work with local communities and networks.

For the past seven years Molebatsi has been living and working in Marikana. His aim is a more peaceful coexistence between rich corporations and the community. But the fraught relationships are epitomised by a phenomenon late at night. When the noise of the day has died down Chris and his neighbours can sometimes hear the hum of a rock drill underground. Some of the shafts here are fairly close to the surface. Walls are cracked by the reverberations from the rock blasts. The intrusion of the mining operations invades even their sleep but they can only dream about the riches of the land that once belonged to their forefathers.

“Since the massacre there have been seven suicides that I know of. Some of them were at the Koppie that day of the killing. People have become depressed, they see no value in life. I have lived in Marikana for 13 years and before 2012 I had heard of only two suicides,” says Molebatsi.

He organises workshops, gathers research and makes sure that when the mining companies trample on human rights it does not go unnoticed. It is a demanding and sometimes thankless task.

Harmful Mining Practices

His organisation Benchmarks has conducted several major research initiatives in the platinum belt of South Africa’s North West province. After the initial study in 2007, called Policy Gap I, the Foundation made recommendations to the key players: Anglo Platinum, Impala Platinum, Lonmin and Xstrata.

The findings showed that despite the great value extracted from platinum mining, there are harmful social, economic and environmental impacts on local communities, and the mining companies have yet to assume their responsibility for the negative consequences of their mining activities.

Several years after the 2007 research the Foundation revisited the situation to check on changes in corporate behaviour and their shocking findings are contained in a report called Policy Gap 6. The corporations surveyed more recently include Anglo, Impala, Lonmin, Xstrata, Aquarius and Royal Bafokeng Platinum Limited.

“We start from the assumption that management and investors will not voluntarily act in the interest of society and the environment,” states the study.

Bench Marks uses as a basis the Principles for Global Corporate Responsibility – Bench Marks for Measuring Business Performance. These principles have been formulated by a number of international faith-based organisations and NGO’s.

But although people like Chris Molebatsi have done backbreaking work to gather the information for the studies the Bench Mark report states:

Overall, we have seen very little improvement in the performance of the companies surveyed… What we have seen is a large increase in corporate advertising, large spreads in newspapers and billboards stating how responsible mining is. Instead, all the companies reviewed here should respond to community concerns over jobs, health care and a safe and healthy environment. Once again we have to report that all the companies surveyed, although participating in the research, have failed on a whole to meet the Principles for Global Corporate Responsibility – Bench Marks for Measuring Business Performance.

Bench Marks Researchers Chris Molebatsi & David van Wyk.

Respiratory Diseases Up By 80%

So where is it that a company like Lonmin, a central player in the recent strike and the shattering events of two years ago, is falling down? We spoke with David van Wyk the Senior Researcher responsible for the Policy Gap 6 report.

“Respiratory diseases have increased by 80% over ten years in Rustenburg, according to doctors we’ve spoken to. When the workers’ lung function is significantly reduced the workers can actually take them to court and so they anticipate this. They’re constantly monitoring and x-raying people. Workers get retrenched when their lung function reaches a certain level. The mines won’t tell you but they do this. Also with regard to HIV/Aids, they don’t tell the workers that they retrench them for that. They say; ‘You are too ill to work’ and retrench them. They are not allowed to do an HIV/Aids test without the workers’ consent but they do it. So now the workers are avoiding the mine clinics and they are flooding the government clinics. The government clinics are overrun and undersupplied. It also creates xenophobic conflict between the community and the mineworkers many of whom are from Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Swaziland and so on,” says Van Wyk.

What Price Platinum

Hidden in the extensive pages of Van Wyk’s probe called Policy Gap 6, lies the real cost of being the world’s number one supplier of platinum. In addition to the health dangers, the report outlines the following problem areas, among others:

• Disregard for community safety indicated by the unguarded rail and road crossings in Luka, Chaneng, Rustenburg Town and Marikana, where most operations are in excess of 40 years old

Mining companies’ disregard for people’s safety. One of several unguarded crossings.

• Issuing of shares to communities and workers. Communities do not receive these shares for free, but have to pay for them, this despite the fact that the current environment virtually allows for corporate land grabs from communities at levels of compensation that are extremely low. The Foundation proposes communities should be compensated for any land lost to mining operations, on a calculation that would give communities a percentage of the value of the mineral reserves. A recent empowerment scheme for the Bapo ba Mogale community that converts mineral royalties into company shares, has been severely criticised

• Companies courting political influence through the deployment of prominent politicians to boards and to senior management.

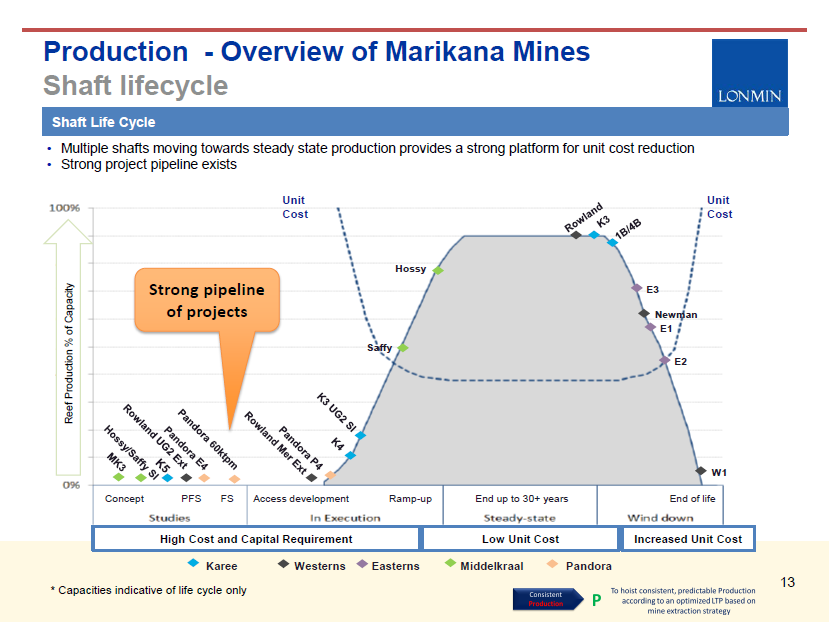

• Some shafts are nearing the end of their lifespan and Bench Marks fears that these will be sold off as BEE projects. In the past mining corporations have sold off their environmental mess and closure responsibilities to unsuspecting BEE “Juniors‟. The Foundation claims the “mess with water in Johannesburg derives exactly from corporations abandoning or selling off mines just before closure”

• The health and welfare status of communities living in close proximity to mines in the Bojanala District in general. The impact of the import of labour rather than the skilling of locals not only deprives locals of economic and employment opportunities, but also impacts on their health and welfare. There is a direct link, say the researchers, between HIV/Aids and the “living-out allowance”. Of great concern here is the appearance of “sexual slavery”. They cite examples of women being brought in from Mozambique for the purpose of “sex slavery” and the renting of daughters to mine workers

• Dust and smoke emissions and respiratory problems experienced by communities

Researchers say it’s not the strikes that will cause the closure of shafts.

Laager Mentalities & Conflict

The Bench Marks report further states:

By excluding communities from real participation and shared ownership in the mines, the companies are excluding themselves from communities. By creating for themselves identities loyal to foreign ownership and shareholding to the extent of even delisting from the JSE and relisting in London, mining corporations are assuming a foreign identity and a foreign personality lacking in patriotism… Operations assume the form of laagers, and management at operational level adopts a laager mentality which can only end in conflict with local communities.

Both Van Wyk and Molebatsi pointed out that there was a “seething anger” in the communities. An anger that is outlined in their report in detail. Wounded workers who have lost their jobs and the shabby way in which families are treated, are fueling some of the fury.

“Very few of the journalists have picked up on this story. The workers who were wounded, many of them lost their jobs, and so there’s been an escalation of suicides in the area. We are also concerned with the fact that there’s very little effective counseling happening. Another worrying aspect is that the Koppie (where the killings of 2012 happened) is right next to the squatter camp. The children witnessed their fathers and brothers and uncles being shot. No one is talking about the trauma that the children suffered and no one is doing something to help these children to cope.”

Another issue affecting the children is that of schooling. The Bench Marks team says Lonmin has offered to pay for schooling but in reality the rural schools have little or no fees and those in the Marikana area are jam-packed because of a rapid increase in the area’s population in recent years.

“So they say they will pay for schools. They constantly say something that sounds good but in reality if you scratch the paint it’s rotten underneath. These corporations have invaded their land, displaced them and are really, really bad neighbours,” says Van Wyk.

He says the strain on community facilities is a potential spark for conflict.

“With the rising unemployment in the rest of the country and since they announced the living out allowance (a stipend of about R 1,800 per month for travel and accommodation) people have been flocking to the mines. When I first came to live here 13 years ago there were just under 180 households. Now there are about 8 000 and in the squatter camp it’s much, much more. The facilities here are for a community of about 2 000 people. The last time Lonmin built a school here was in 2003. You have all these children crammed into a few schools,” says Molebatsi.

What About the Bereaved?

I asked Chris Molebatsi and David van Wyk what had been done for the wounded and bereaved families in the last two years. Molebatsi told me about a widow who had received a R 67 000 Provident Fund payout and adds: “But then I met a man with a bullet still lodged in his head. He is walking around jobless.”

In this regard Van Wyk has an alarming story to tell. He describes a meeting attended by Bench Marks and a Norwegian government official in the gleaming Lonmin boardroom:

“We asked them, ‘so what are you going to do for these families who lost their breadwinners’. Lonmin’s standard answer is; ‘We went to the family and asked for a brother to replace him.”

If this chilling story is accurate it reduces the workforce to nothing more than automatons that can be replaced like the parts of machinery.

Molebatsi says he has spoken with widows who are prepared to go and work on the mines to make up for the income they have lost when their husbands were killed. But Bench Marks research shows that while women are now allowed equal pay for equal work, conditions underground leave much to be desired.

“There are huge issues around women in mining. The mining charter says you must have a certain percentage of women so the companies go for meeting the figure without changing anything in the way that the mine operates. This puts women at a great disadvantage and in great danger. They still employ the 19th Century practice of going to the Chiefs to find labour. They’ve taken the issue of finding female workers to the Chiefs as well as local councilors. The councilors have abused that to trade sex for jobs. I’ve got women on camera, on video, speaking about this kind of exploitation. We were visiting an Anglo mine and the personnel manager told me; ‘You know it’s so bad for women that at month end you have to look where you walk because you might step on condoms’. He spoke about the sexual transactions that are happening underground that are absolutely terrible. It was about a month later that Pinky was killed,” says Van Wyk.

“My dreams now are dark, black,” says a Marikana widow.

Pinky Mosiane was murdered in a Rustenburg mineshaft on February 6 in 2012, six months before the start of the strike in Marikana. Her body was found lying in a pool of blood with a used condom next to her. She may possibly have been raped by several men. More than two years later the murder and rape case is still dragging on in the courts in the North West province. The lack of action in Pinky’s case isn’t about the usual incompetence, says a report in the Daily Maverick, it’s about a sex for bonuses scandal that neither the unions nor the mines seem to want to acknowledge. It took police 20 months to arrest a suspect in connection with the death of Mosiane, who was 35 at the time.

Workers Tear Gassed, Beaten & Arrested

Given the soul searching of the past two years, one could easily assume that there is now a different relationship between the police and the community at Marikana. But Van Wyk tells a story that indicates we’ve made very little progress since the 2012 tragedy:

“Two weeks ago at Tharisa mine in Marikana – it’s a new mine – they relocated a whole community of people away to a nearby township. Then they had a blast in the afternoon. The rocks came flying through people’s roofs. The next day the people marched to the mine to say; ‘You relocated us to this township but you didn’t tell us you were going to blast and put our lives in danger. Surely you should have relocated us to a place that was safe?’ The police responded by tear gassing the community, putting dogs onto them and arresting them. The community was saying: ‘Look we’re not the ones who committed a crime here, it’s our constitutional rights that have been affected. Why is the police acting against us instead of the mining company?’ If you speak to the Monitors throughout the platinum belt they will tell you they have no faith in the police. Some of our Monitors got beaten up on Human Rights Day for having a Human Rights protest around mining in Chaneng Village. We had to find lawyers but invariably these cases get thrown out because they are baseless. But they took young people just out of school, in their early 20s through the trauma of being arrested, throwing them in a cell, slapping them around, kicking them and carrying on and you expect people to have faith in the police.”

The plight of South Africa’s mineworkers stands out starkly against a backdrop of a nation that sits atop the world’s largest platinum reserves. Together with Zimbabwe we supply about 87% of this rare metal. So how come we are not using this considerable muscle to build a better industry for our workers?

“Our mining is in a big mess. We need to take charge. You don’t need to nationalise, there are ways… For example with platinum you can create a centralised buying agency of the state. It will buy all platinum from producers and then resell it on global markets. That way you can buy the platinum slightly below market value in times of high prices and slightly above market value in times of low prices and thereby ensure continuity and jobs. It was done quite a lot in the 50s and 60s when we followed more Keynesian Economic Policies. Canada, Russia and the platinum industry in South Africa colluded in the 1940s and I’ve got evidence for that. We can dictate the prices and slow down production if we want to think about our children’s future and if we want to minimise the social and environmental impact. But everyone wants to be a millionaire and so we pay a huge price,” says Van Wyk.

Simmering Tensions

Molebatsi who spends his days going from door to door in the community warns that the tensions that have ripped Marikana apart are far from over:

“There’s going to be a lot of conflict and people are still going to die. I feel very bad. All these things are happening because the death of people is actually benefitting others and it’s painful because you are talking about families, kids and women. But for some people it doesn’t matter as long as they can drive Porsche cars and live in mansions. It is saddening. We can’t stop it, we are helpless. It is the people who are benefitting who can stop it. We have been saying there needs to be change that can favour everybody but nobody cares to listen. There are people who have the powers but they have personal interest. South Africa being as rich as it is, there are shacks everywhere and people go to bed without food. Then there are those who are rich overnight. Those are the people who will not want to see anyone tampering with the current system. We are just spectators and they know very well that they will keep shouting but there is nothing they are going to do.”

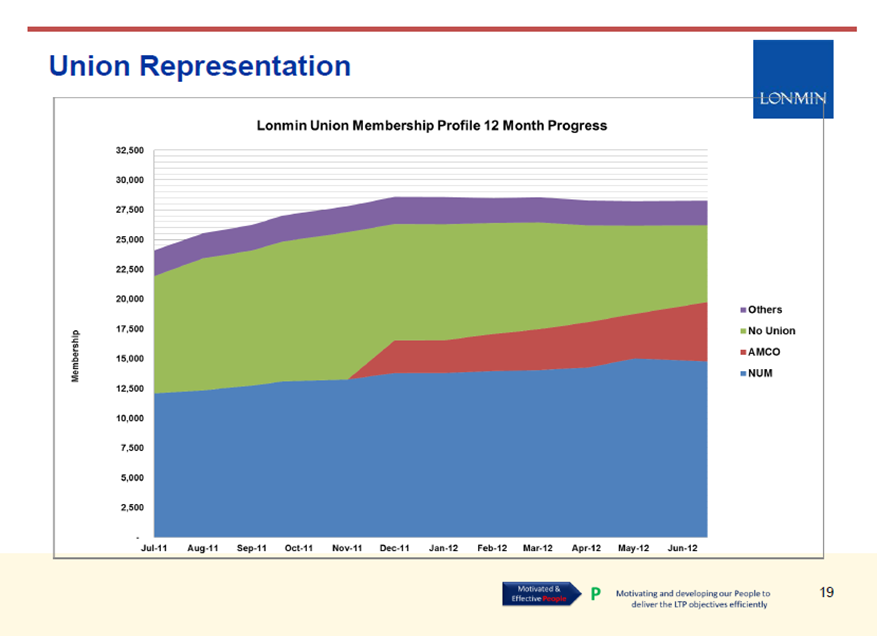

And it’s not only the tensions between the rich and the poor on the platinum belt that are a simmering threat (World Economic Forum Statistics show that ours is one of the world’s most unequal societies globally). Waiting in the wings of this drama is the unions’ battles for the hearts, minds and cash contributions of the workforce. The events of the last two years have meant that the mighty National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) was toppled by the relative newcomer the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (Amcu)

The rising fortunes of Amcu.

“In July 2012 AMCU posed no threat to NUM. Its only growth was among non-unionised workers at Lonmin. In fact when the rock drill operators marched to Lonmin’s offices in late July 2012, rejecting the collective bargaining arrangement agreed with NUM, Lonmin management did not know how to deal with the situation. They called NUM to intervene, but NUM responded by saying that the rock drill operators were not their members. Lonmin then called AMCU to intervene. AMCU also noted that the rock drill operators were not their members but agreed to come and talk to the workers. Had NUM agreed to intervene, it would today probably still be the majority union at Lonmin. NUM’s intransigence was in fact its own undoing,” recalls David Van Wyk.

The final word in the platinum saga goes to the women at the Farlam Commission of Inquiry: “The widows have said; ‘Look we are sitting here at the Commission day in and day out. We live in hotels. We are eating good food. In the meantime our children and families back home are starving.” This is a clear indication that Lonmin isn’t doing anything for the bereaved families despite any claims to the contrary,” says Van Wyk.

We have sent a detailed request for comment to both the Government and Lonmin. The request is published elsewhere on this page.

Platinum Uses

In addition to being adornment and essential for the so-called ‘Cat’s’ of the auto industry, platinum also has a range of industrial uses. The Platinum Group Metals (PGM’s) are:

• Used in the manufacture of nitric acid, a key ingredient in fertilizers

• Used computer hard disks

• Essential for the catalysts of battery-like devices for generating electric power called fuel cells.

From the mines in Rustenburg the PGM’s go to markets in mostly North America, China and Japan.