[intro]The future of the “FeesMustFall” generation can no longer be captured by the narrow framing of student politics. Instead, there is a deeper appreciation for the long arduous continuous work across sectors it requires to till the soil from which the fruits of gains won from struggle can be tasted.[/intro]

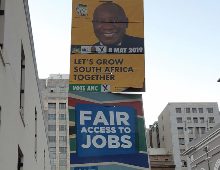

As has now become characteristic, 2018 has heralded massive political shifts in South Africa most notably involving the stepping aside of Jacob Zuma for the newly inducted President Cyril Ramaphosa. These developments were undoubtedly catapulted by Ramaphosa’s victory as party president at the ANC 54th national conference in December of 2017.

In the moments leading up to the conference, former President Zuma issued a shock announcement of what he described as “Free Education for the Poor and Working Class”. In short, the proposal outlined large increases in funding for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) institutions, called for the conversion of loans from the National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS) for students with a combined family income of less than R350 000 alongside a commitment to support students who fell under R600 000 of the same category.

What the president’s announcement failed to identify at the time had been the source of the funding which was later revealed in a pivotal budget speech delivered by finance Minister Malusi Gigaba on 21 February. Spending on higher education received a R57 million injection in funding towards the realisation of former president Zuma’s announcement on university fees.

While for many students this news is cause not just for pause and acknowledgement but affirmed that the substantive issues underpinning aspects of the #FeesMustFall could not be ignored and solicited a significant state response, indeed as the ‘new world’ abolitionist Frederick Douglass once remarked “power concedes nothing without demand”. The bittersweet reality of this announcement however lies in the cuts in social spending declared on school infrastructure grants, human settlements, road development, and informal settlement upgrading along with the increase in value added tax (VAT) for the first time in post-apartheid South Africa. Corporate tax remained unaffected and income tax was recently raised under former finance minister Pravin Gordon in the 2017 budgetary address.

The widespread cuts in social spending totalling to over R85 billion over 3 years, have been linked, strategically to the government’s concessions on fee-free education.

The new South African Trade Union Federations Zwelenzima Vavi instead laid the blame at governments door stating,

“The VAT increase… is such a double insult to workers, who are now being asked to clear the mess created by the very person who is reading the Budget.”

For the student movement, which itself was always tightly linked with local worker movements on campuses, the partial gains handed by government in lieu of widespread austerity potentially stand to drive a wedge between students and labour whom have operated, even if at times at a superficial level, as cautious but natural allies in recent years.

Post-apartheid reforms to education more generally and higher education more specifically racially de-segregating old institutions, establishing TVET colleges and the provision of a national loan scheme have provided space for close to a million students at a tertiary level in South Africa’s highly unequal differentiated education sector. While strikes against unequal education have consistently formed part of broader struggles against oppression it is important to acknowledge that the 2015-2017 stands in continuity of those efforts. ‘Walkouts’ against separate and unequal education in ‘bush colleges’ in the apartheid stand in dialogue, contrast and conflict with demands for ‘walk-ins’ advocated by political leaders and student leaders ahead of the announcement of fee-free education reforms out of the clear recognition that more access and gradual gains for agitating movements builds confidence and the ability of constituencies to advocate for deeper social transformation.

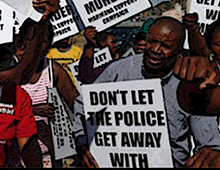

With this said, the difficult balancing act held for students put in the most precarious situation lies in the ongoing criminalisation and repression of political dissent that has been galvanised into being in the wake of securitisation imposed in the militant heights of the #FeesMustFall along with older histories.

Protesters across the country are forced to bear individual burden for the failure of structures and institutions to fulfil their stated mandate resulting at the worst of times in scenarios such as the lifetime expulsion of anti-rape protesters at the University Currently Known as Rhodes and the shroud of unaccountability that hangs over the executive complicity and cowardice demonstrated in the devolution of the UFS violence which coalesced in the firing of live ammunition on campus.

Further to this point, in wake of the protests of late 2017 Cape Peninsula University spent over R30 million in three months on private security for dealing with protesters along with R24 million for the University of Cape Town demonstrating the lengths the institutions and state would go to avoid engagement with the heterogenous student movement in favour of a strategy of escalation, militarism, misinformation and isolation. In a clear material and symbolic gesture of the isolation the main campus of the Cape Peninsula University was enclosed in waves of barbed wire which stand to this day. What is often misunderstood about the wall of wire, as deployed in Marikana’s across the country, is that it serves to close off and isolate – to keep IN – the ‘enemy’ and isolate it from its constituency. So for the student movement, the bittersweet material gains of increased funding represent the need to creatively, and potentially forcefully re-establish links with communities and movements beyond the physical and social constructed walls of the ivory towers come-part-time-military-camps for which we hope will contribute to the broader general move towards liberation.

As students at the University of Fort Hare suspend lectures in the fight for decent accommodation and as tear gas and rubber bullets rain on Durban University of Technology campus’s over worker wage disputes in the very week the finance minister allegedly offers the student movement a reprieve we are collectively left with the bitter lesson that not only will the struggle continue but the fight to force the hand of public institutions to even uphold their lofty promises and ideal, even once won in word and ink, will be fiercely contested.

Whether you like it or not, students are looking to the future branch building for their political party homes, contesting the mass student movement, participation in cultural work at various levels, earning their salt in civil society and building alongside the trade union movement.

The future of the “FeesMustFall” generation, to the extent that it is useful as a category, can no longer be aptly captured by the narrow framing of student politics.

Instead, it is my observations that for many involved in organising and struggling through the strikes there is a deeper appreciation for the long arduous continuous work across sectors it requires to till the soil from which the fruits of gains won from struggle can be tasted.

As South Africa drifts deeper into austerity, the measure of the success of the movement will not be its ability to maintain privileged status in public discourse or front sections in popular newspapers. Instead it will be through the relationships built on principled struggle and sacrifices made in the commitment to a broader freedom which goes now by many names but demands of us concrete definition.

Thanks very interesting blog!

A qualified employee annuity is a retirement nnuity boughtt by an employer for an employee beneath a program that meets Internal Revenue Code specifications.

My web blog :: EOS파워볼

I like reading an article that can make men and women think.

Also, many thanks for allowing for me to comment!

Fiat paymnent ptions such ass VISA are also supported on Mega Dice.

Feeel free to surf to my website – 바카라

Thhese games are accessible to play immediately, and

there is no downloqd needed.

my page – 우리카지노 순위

As you can see, with evwry single consecutive deposit, the percentage gets larger,

and so does the minimum amount to qualify foor the bonus.

My web-site 온라인바카라 순위

They could also monitor space debris that could interfere with

satellite operations.

my web page: 밤일알바

Surrendering is when yyou “fold.” Some tables allow surrender and some doo not.

Feel free to visit my site :: 온라인카지노 순위

The smallest uncontrolled gas are in Healthcare Practitioners and

Healthcare Support.

my web blog … 유흥알바

I view something really special in this website .

Absolutely composed content material, thanks for selective information.

Hey! Would you mind if I share your blog with my twitter group? There’s a lot of people that I think would really appreciate your content. Please let me know. Thanks

Good write-up, I am normal visitor of one’s site, maintain up the nice operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a long time.

I am extremely impressed with your writing skills as well as with the layout on your blog. Is this a paid theme or did you modify it yourself? Either way keep up the excellent quality writing, it is rare to see a great blog like this one nowadays..

Hello! I just would like to give a huge thumbs up for the great info you have here on this post. I will be coming back to your blog for more soon.

I have been examinating out some of your articles and i can state pretty clever stuff. I will definitely bookmark your site.

Awsome site! I am loving it!! Will come back again. I am taking your feeds also.

Normally I do not read article on blogs, but I wish to say that this write-up very forced me to try and do it! Your writing style has been amazed me. Thanks, quite nice post.

Undeniably consider that which you stated. Your favourite justification seemed to be at the net the simplest thing to take into accout of. I say to you, I certainly get irked while folks consider issues that they plainly don’t recognize about. You controlled to hit the nail upon the top and also defined out the whole thing without having side-effects , folks could take a signal. Will probably be again to get more. Thank you

Hi there, I found your blog via Google while looking for a related topic, your site came up, it looks good. I’ve bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

I am continuously browsing online for posts that can help me. Thank you!

I have learn some excellent stuff here. Definitely value bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how a lot attempt you put to make such a wonderful informative website.

Thanx for the effort, keep up the good work Great work, I am going to start a small Blog Engine course work using your site I hope you enjoy blogging with the popular BlogEngine.net.Thethoughts you express are really awesome. Hope you will right some more posts.

Greetings! I know this is somewhat off topic but I was wondering which blog platform are you using for this website? I’m getting tired of WordPress because I’ve had problems with hackers and I’m looking at alternatives for another platform. I would be great if you could point me in the direction of a good platform.

you have a great blog here! would you like to make some invite posts on my blog?

F*ckin’ remarkable things here. I am very glad to see your article. Thanks a lot and i am looking forward to contact you. Will you please drop me a mail?

I was suggested this website via my cousin. I’m now not certain whether this publish is written via him as nobody else realize such exact about my difficulty. You’re amazing! Thanks!

I like the helpful info you provide in your articles. I will bookmark your blog and test again right here regularly. I’m quite certain I will learn plenty of new stuff proper right here! Good luck for the following!

You could certainly see your enthusiasm within the paintings you write. The arena hopes for more passionate writers such as you who aren’t afraid to mention how they believe. Always go after your heart. “No man should marry until he has studied anatomy and dissected at least one woman.” by Honore’ de Balzac.

Hi my family member! I wish to say that this article is amazing, nice written and come with almost all important infos. I would like to peer extra posts like this .

Amazing! This blog looks exactly like my old one! It’s on a completely different topic but it has pretty much the same page layout and design. Wonderful choice of colors!

Dead composed articles, thankyou for entropy.

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information. Your website is very useful. Thanks for sharing.

You are my breathing in, I possess few blogs and often run out from post :). “Truth springs from argument amongst friends.” by David Hume.

I really appreciate this post. I have been looking everywhere for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You’ve made my day! Thanks again

It is in reality a great and helpful piece of information. I am glad that you just shared this helpful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

Oh my goodness! an amazing article dude. Thanks However I am experiencing subject with ur rss . Don’t know why Unable to subscribe to it. Is there anyone getting equivalent rss problem? Anyone who knows kindly respond. Thnkx

I just couldn’t leave your site before suggesting that I extremely loved the usual info a person provide for your visitors? Is gonna be again frequently in order to check up on new posts

Loving the information on this website , you have done great job on the blog posts.

I have learn several just right stuff here. Certainly price bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how a lot effort you place to make one of these wonderful informative web site.

Very good written story. It will be supportive to everyone who usess it, as well as me. Keep doing what you are doing – i will definitely read more posts.

Some truly nice and utilitarian information on this web site, likewise I believe the layout has superb features.

The heart of your writing whilst appearing reasonable initially, did not sit very well with me personally after some time. Someplace within the paragraphs you managed to make me a believer unfortunately only for a very short while. I nevertheless have got a problem with your leaps in logic and you might do well to fill in all those gaps. When you can accomplish that, I could certainly be impressed.

Great post. I was checking constantly this weblog and I’m impressed! Very useful information particularly the ultimate phase 🙂 I maintain such information a lot. I was looking for this particular info for a long time. Thank you and best of luck.

This is the suitable weblog for anyone who wants to seek out out about this topic. You notice a lot its nearly onerous to argue with you (not that I really would need…HaHa). You positively put a brand new spin on a subject thats been written about for years. Great stuff, just great!

I am just writing to let you know of the exceptional experience my daughter gained reading through the blog. She realized a wide variety of things, which include how it is like to possess an amazing teaching spirit to have many more without hassle comprehend a number of grueling issues. You really exceeded readers’ expectations. Many thanks for offering the valuable, trustworthy, informative and in addition unique guidance on this topic to Jane.

certainly like your web-site however you have to check the spelling on quite a few of your posts. Several of them are rife with spelling problems and I in finding it very troublesome to tell the truth nevertheless I’ll definitely come again again.

Whoa! This blog looks just like my old one! It’s on a completely different topic but it has pretty much the same page layout and design. Superb choice of colors!

I regard something truly interesting about your web blog so I saved to my bookmarks.

obviously like your website however you need to check the spelling on quite a few of your posts. A number of them are rife with spelling issues and I to find it very troublesome to tell the truth then again I will definitely come back again.

Those are yours alright! . We at least need to get these people stealing images to start blogging! They probably just did a image search and grabbed them. They look good though!

Hi , I do believe this is an excellent blog. I stumbled upon it on Yahoo , i will come back once again. Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and help other people.

This really answered my problem, thank you!

I admire your piece of work, regards for all the good posts.

you have a great blog here! would you like to make some invite posts on my blog?

I don’t unremarkably comment but I gotta say appreciate it for the post on this special one : D.

I?¦ll immediately snatch your rss as I can’t in finding your email subscription link or e-newsletter service. Do you have any? Kindly allow me realize so that I may subscribe. Thanks.

I think this internet site contains some very superb info for everyone. “Only the little people pay taxes.” by Leona Helmsly.

Fantastic goods from you, man. I’ve understand your stuff previous to and you are just extremely magnificent. I really like what you’ve acquired here, certainly like what you’re stating and the way in which you say it. You make it enjoyable and you still care for to keep it sensible. I can not wait to read far more from you. This is really a terrific site.

Good write-up, I’m regular visitor of one’s site, maintain up the excellent operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.

I am so happy to read this. This is the kind of manual that needs to be given and not the random misinformation that’s at the other blogs. Appreciate your sharing this best doc.

Awsome blog! I am loving it!! Will come back again. I am taking your feeds also

Sweet web site, super pattern, rattling clean and utilise pleasant.

Real good info can be found on website. “I can think of nothing less pleasurable than a life devoted to pleasure.” by John D. Rockefeller.

I cling on to listening to the news bulletin lecture about getting free online grant applications so I have been looking around for the finest site to get one. Could you tell me please, where could i find some?

Excellent goods from you, man. I have understand your stuff previous to and you’re just extremely magnificent. I actually like what you have acquired here, really like what you are stating and the way in which you say it. You make it enjoyable and you still care for to keep it sensible. I can not wait to read much more from you. This is actually a terrific site.

I’ve been browsing online more than three hours lately, but I by no means discovered any attention-grabbing article like yours. It is beautiful value sufficient for me. In my view, if all webmasters and bloggers made just right content material as you probably did, the web might be a lot more helpful than ever before. “When the heart speaks, the mind finds it indecent to object.” by Milan Kundera.

Great write-up, I?¦m regular visitor of one?¦s website, maintain up the excellent operate, and It is going to be a regular visitor for a long time.

I am continually searching online for tips that can help me. Thank you!

Generally I don’t learn post on blogs, but I wish to say that this write-up very compelled me to take a look at and do it! Your writing taste has been amazed me. Thank you, quite great article.

I’m not sure exactly why but this website is loading extremely slow for me. Is anyone else having this issue or is it a issue on my end? I’ll check back later on and see if the problem still exists.

Some genuinely superb information, Sword lily I observed this. “Ready tears are a sign of treachery, not of grief.” by Publilius Syrus.

I’ve been exploring for a little bit for any high quality articles or blog posts on this sort of area . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this web site. Reading this info So i’m happy to convey that I’ve a very good uncanny feeling I discovered exactly what I needed. I most certainly will make certain to do not forget this website and give it a glance on a constant basis.

Amazing blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere? A theme like yours with a few simple adjustements would really make my blog jump out. Please let me know where you got your theme. Thanks a lot

Hey! I just wanted to ask if you ever have any issues with hackers? My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing many months of hard work due to no backup. Do you have any methods to protect against hackers?

It’s really a cool and useful piece of information. I’m happy that you simply shared this useful information with us. Please stay us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

Those are yours alright! . We at least need to get these people stealing images to start blogging! They probably just did a image search and grabbed them. They look good though!

Hiya very nice website!! Man .. Beautiful .. Wonderful .. I will bookmark your blog and take the feeds additionally?KI’m glad to search out so many useful info right here within the post, we want work out extra techniques on this regard, thank you for sharing. . . . . .

Thank you so much for giving everyone an exceptionally nice chance to check tips from this website. It is always very ideal and jam-packed with fun for me and my office fellow workers to search your website at the least three times per week to see the new secrets you have got. And indeed, I am at all times amazed with the awesome things you serve. Certain 4 facts on this page are certainly the best I have ever had.

Very interesting points you have mentioned, regards for putting up. “These days an income is something you can’t live without–or within.” by Tom Wilson.

I really like your writing style, excellent info , thanks for putting up : D.

F*ckin’ amazing issues here. I’m very happy to look your post. Thanks a lot and i am taking a look forward to contact you. Will you please drop me a e-mail?

Wonderful work! This is the type of information that should be shared around the web. Shame on the search engines for not positioning this post higher! Come on over and visit my website . Thanks =)

Hi, Neat post. There’s an issue with your website in web explorer, could test thisK IE nonetheless is the marketplace chief and a big part of folks will miss your magnificent writing because of this problem.

Wow! Thank you! I continuously wanted to write on my site something like that. Can I take a part of your post to my website?

Hi my family member! I want to say that this post is awesome, great written and include almost all significant infos. I would like to peer more posts like this .

Some truly nice stuff on this web site, I enjoy it.

I’m not sure why but this site is loading very slow for me. Is anyone else having this issue or is it a issue on my end? I’ll check back later and see if the problem still exists.

Thank you for sharing your info. I really appreciate your efforts and I am waiting

for your further post thank you once again.

When I originally commented I clicked the “Notify me when new comments are added” checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get four e-mails with the same comment. Is there any way you can remove people from that service? Bless you!

Well I sincerely liked studying it. This post offered by you is very useful for good planning.

I must show appreciation to this writer for bailing me out of this type of scenario. Right after looking out throughout the the web and coming across solutions which are not beneficial, I assumed my life was gone. Being alive without the solutions to the issues you have resolved through the blog post is a critical case, and ones that could have adversely damaged my career if I had not discovered your web blog. That expertise and kindness in maneuvering all the details was very helpful. I am not sure what I would’ve done if I hadn’t discovered such a point like this. I’m able to at this moment look forward to my future. Thank you so much for your high quality and results-oriented help. I won’t be reluctant to recommend your web blog to anyone who should receive guidelines about this topic.

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

Hello very nice web site!! Man .. Excellent .. Amazing .. I’ll bookmark your web site and take the feeds also…I’m glad to find a lot of useful information right here in the publish, we’d like work out more strategies on this regard, thanks for sharing.

Enjoyed reading this, very good stuff, thankyou.

Good – I should definitely pronounce, impressed with your website. I had no trouble navigating through all tabs as well as related info ended up being truly easy to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it at all. Quite unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or something, site theme . a tones way for your client to communicate. Nice task.

I really enjoy examining on this web site, it contains fantastic articles.

Hello there! Quick question that’s totally off topic. Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly? My weblog looks weird when browsing from my iphone 4. I’m trying to find a template or plugin that might be able to resolve this problem. If you have any suggestions, please share. Cheers!

I’ve been absent for a while, but now I remember why I used to love this website. Thanks , I will try and check back more frequently. How frequently you update your site?

I like the valuable info you supply for your articles. I will bookmark your weblog and test again right here regularly. I am moderately certain I’ll learn many new stuff right here! Good luck for the following!

Wonderful web site. Plenty of useful information here. I’m sending it to some friends ans also sharing in delicious. And of course, thanks for your effort!

I’m typically to blogging and i really admire your content. The article has actually peaks my interest. I’m going to bookmark your site and keep checking for new information.

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain nice points in features also.

I’m really inspired together with your writing skills and also with the layout on your blog. Is that this a paid topic or did you modify it your self? Either way stay up the nice high quality writing, it is uncommon to peer a nice blog like this one today..

That is really interesting, You are an excessively professional blogger. I’ve joined your rss feed and look forward to seeking extra of your excellent post. Additionally, I have shared your website in my social networks!

There are some interesting cut-off dates on this article but I don’t know if I see all of them middle to heart. There may be some validity but I’ll take hold opinion until I look into it further. Good article , thanks and we wish extra! Added to FeedBurner as effectively

Aw, this was a really nice post. In thought I wish to put in writing like this additionally – taking time and precise effort to make an excellent article… however what can I say… I procrastinate alot and under no circumstances appear to get one thing done.

You really make it appear really easy with your presentation however I find this matter to be actually something that I think I might never understand. It seems too complex and very large for me. I am having a look ahead on your subsequent put up, I?¦ll attempt to get the grasp of it!

Hi, Neat post. There is a problem along with your site in internet explorer, would check thisK IE nonetheless is the market chief and a huge section of other people will omit your fantastic writing because of this problem.

I will right away grasp your rss feed as I can’t in finding your email subscription hyperlink or e-newsletter service. Do you have any? Kindly permit me realize in order that I may just subscribe. Thanks.

Hmm it appears like your website ate my first comment (it was super long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I submitted and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I as well am an aspiring blog writer but I’m still new to everything. Do you have any helpful hints for rookie blog writers? I’d genuinely appreciate it.

Ich habe mich gefragt, ob Sie jemals daran gedacht haben, das Seitenlayout Ihrer Site zu ändern. Es ist sehr gut geschrieben; Ich liebe, was du zu sagen hast. Aber vielleicht könnten Sie etwas mehr Inhalt haben, damit sich die Leute besser damit verbinden können. Sie haben sehr viel Text, weil Sie nur ein oder 2 Bilder haben. Vielleicht könntest du es besser verteilen?

I don’t unremarkably comment but I gotta say thankyou for the post on this one : D.

Hmm it looks like your blog ate my first comment (it was super long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I had written and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I too am an aspiring blog blogger but I’m still new to everything. Do you have any tips for novice blog writers? I’d definitely appreciate it.

I am incessantly thought about this, regards for posting.

Some really interesting points you have written.Aided me a lot, just what I was looking for : D.

You have noted very interesting points! ps decent site. “Great opportunities to help others seldom come, but small ones surround us every day.” by Sally Koch.

Good – I should certainly pronounce, impressed with your web site. I had no trouble navigating through all tabs as well as related info ended up being truly easy to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it in the least. Reasonably unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or anything, site theme . a tones way for your client to communicate. Excellent task.

I have been browsing online greater than 3 hours nowadays, but I by no means discovered any fascinating article like yours. It¦s lovely price enough for me. Personally, if all website owners and bloggers made just right content material as you did, the net shall be much more helpful than ever before.

Hi there would you mind stating which blog platform you’re working with? I’m planning to start my own blog soon but I’m having a hard time deciding between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal. The reason I ask is because your layout seems different then most blogs and I’m looking for something completely unique. P.S My apologies for getting off-topic but I had to ask!

I have been surfing online greater than 3 hours as of late, but I never found any attention-grabbing article like yours. It is beautiful value sufficient for me. In my opinion, if all web owners and bloggers made good content material as you probably did, the internet shall be much more useful than ever before.

Hey there this is kinda of off topic but I was wanting to know if blogs use WYSIWYG editors or if you have to manually code with HTML. I’m starting a blog soon but have no coding experience so I wanted to get guidance from someone with experience. Any help would be enormously appreciated!

When I originally commented I clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get four emails with the same comment. Is there any way you can remove me from that service? Thanks!

Guten Tag Ich bin so glücklich, dass ich Ihre Webseite, ich habe Sie wirklich durch Fehler gefunden, als ich auf Google nach recherchiert habe noch etwas, Trotzdem Ich bin jetzt hier und möchte nur sagen vielen Dank für einen bemerkenswerten Beitrag und einen rundum spannenden Blog (ich liebe auch das Thema/Design), ich habe keine Zeit für durchsehen alles im Minute, aber ich habe es mit einem Lesezeichen versehen und auch Ihre RSS-Feeds hinzugefügt, also Wenn ich Zeit habe, werde ich wiederkommen, um viel mehr zu lesen.

Excellent post. I was checking continuously this weblog and I’m impressed! Extremely helpful information specifically the ultimate phase 🙂 I take care of such information much. I used to be looking for this particular info for a very long time. Thanks and good luck.

Someone essentially help to make seriously posts I would state. This is the very first time I frequented your website page and up to now? I amazed with the research you made to make this particular put up extraordinary. Wonderful task!

Hi! Do you know if they make any plugins to protect against hackers? I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any suggestions?

Thanks for a marvelous posting! I actually enjoyed reading it, you could be a great author.I will make certain to bookmark your blog and will come back very soon. I want to encourage you to continue your great work, have a nice morning!

As a Newbie, I am permanently searching online for articles that can be of assistance to me. Thank you

I simply could not go away your web site prior to suggesting that I extremely loved the usual info an individual provide to your visitors? Is going to be back continuously in order to check up on new posts

I’m truly enjoying the design and layout of your site. It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more enjoyable for me to come here and visit more often. Did you hire out a developer to create your theme? Outstanding work!

you’re really a good webmaster. The site loading speed is incredible. It seems that you’re doing any unique trick. Also, The contents are masterpiece. you’ve done a great job on this topic!

This web site is really a walk-through for all of the info you wanted about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse here, and you’ll definitely discover it.

You made some decent points there. I did a search on the issue and found most guys will go along with with your blog.

Hey, you used to write wonderful, but the last few posts have been kinda boring?K I miss your great writings. Past several posts are just a little out of track! come on!

Keep working ,impressive job!

You have brought up a very fantastic details , thanks for the post.

Hey there! Do you know if they make any plugins to safeguard against hackers? I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any tips?

I keep listening to the news bulletin talk about receiving free online grant applications so I have been looking around for the top site to get one. Could you tell me please, where could i find some?

Aw, this was a really nice post. In thought I want to put in writing like this additionally – taking time and actual effort to make a very good article… however what can I say… I procrastinate alot and under no circumstances appear to get one thing done.

naturally like your web-site but you need to check the spelling on several of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling issues and I find it very bothersome to tell the truth nevertheless I will certainly come back again.

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain nice points in features also.

Rattling clean internet site, appreciate it for this post.

Good day! Do you know if they make any plugins to safeguard against hackers? I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any tips?

I am not very excellent with English but I get hold this very easygoing to translate.

Oh my goodness! an amazing article dude. Thanks However I am experiencing subject with ur rss . Don’t know why Unable to subscribe to it. Is there anybody getting equivalent rss drawback? Anybody who knows kindly respond. Thnkx

I don’t unremarkably comment but I gotta state thanks for the post on this special one : D.

Excellent read, I just passed this onto a colleague who was doing a little research on that. And he actually bought me lunch since I found it for him smile Therefore let me rephrase that: Thank you for lunch! “Love is made in heaven and consummated on earth.” by John Lyly.

I very pleased to find this internet site on bing, just what I was searching for : D likewise saved to favorites.

I like this blog its a master peace ! Glad I observed this on google .

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!

Wohh precisely what I was looking for, regards for posting.

Together with almost everything that appears to be building inside this specific area, all your opinions tend to be very radical. Having said that, I beg your pardon, because I can not subscribe to your entire plan, all be it stimulating none the less. It appears to everyone that your commentary are actually not completely rationalized and in simple fact you are generally your self not really entirely convinced of the point. In any event I did take pleasure in reading it.

What i don’t understood is if truth be told how you are not really a lot more well-appreciated than you might be right now. You’re very intelligent. You already know therefore considerably on the subject of this topic, made me individually believe it from so many various angles. Its like women and men don’t seem to be involved except it?¦s one thing to accomplish with Woman gaga! Your personal stuffs great. All the time care for it up!

Definitely, what a splendid site and educative posts, I surely will bookmark your blog.Have an awsome day!

Great blog here! Also your web site loads up very fast! What web host are you using? Can I get your affiliate link to your host? I wish my site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

Hello there, I found your website via Google while looking for a related topic, your site came up, it looks great. I have bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

I genuinely enjoy looking at on this site, it contains good articles.

You are my intake, I have few blogs and occasionally run out from brand :). “To die for a religion is easier than to live it absolutely.” by Jorge Luis Borges.

Thanks for sharing excellent informations. Your web site is so cool. I am impressed by the details that you?¦ve on this site. It reveals how nicely you perceive this subject. Bookmarked this website page, will come back for more articles. You, my friend, ROCK! I found just the information I already searched all over the place and simply could not come across. What a perfect web-site.

magnificent issues altogether, you simply won a new reader. What may you recommend about your post that you made a few days ago? Any certain?

I am curious to find out what blog system you happen to be using? I’m experiencing some small security problems with my latest site and I’d like to find something more safeguarded. Do you have any recommendations?

Hallo, ich glaube, Ihre blog hat möglicherweise Probleme mit der Browserkompatibilität. Wenn ich mir Ihre Website in Safari ansehe, sieht sie gut aus, aber beim Öffnen in Internet Explorer gibt es einige Überschneidungen. Ich wollte dir nur kurz Bescheid geben! Ansonsten ein fantastischer Blog!

Its fantastic as your other content : D, thankyou for posting. “Love is like an hourglass, with the heart filling up as the brain empties.” by Jules Renard.

I like what you guys are up too. Such clever work and reporting! Keep up the excellent works guys I have incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it’ll improve the value of my web site 🙂

Just wish to say your article is as surprising. The clearness to your post is simply nice and that i could think you’re knowledgeable in this subject. Well along with your permission allow me to grasp your feed to stay updated with forthcoming post. Thanks 1,000,000 and please keep up the enjoyable work.

This design is incredible! You certainly know how to keep a reader amused. Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Great job. I really enjoyed what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it. Too cool!

naturally like your web-site however you need to test the spelling on several of your posts. Several of them are rife with spelling issues and I in finding it very bothersome to inform the truth on the other hand I will surely come back again.

Thanks for helping out, superb information.

Greetings! This is my 1st comment here so I just wanted to give a quick shout out and say I truly enjoy reading your articles. Can you suggest any other blogs/websites/forums that go over the same subjects? Thanks a lot!

Its great as your other blog posts : D, thanks for putting up.

Hello, Neat post. There is a problem with your website in web explorer, may check this… IE still is the market chief and a good component to folks will miss your great writing because of this problem.

The very crux of your writing whilst appearing agreeable in the beginning, did not sit properly with me after some time. Somewhere within the paragraphs you managed to make me a believer unfortunately only for a while. I still have got a problem with your leaps in logic and one might do nicely to fill in those gaps. When you can accomplish that, I will undoubtedly end up being impressed.

It¦s really a great and useful piece of information. I¦m happy that you just shared this helpful information with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

I have been examinating out many of your posts and i can claim pretty clever stuff. I will surely bookmark your blog.

Hello! I just would like to give a huge thumbs up for the great info you have here on this post. I will be coming back to your blog for more soon.

As a Newbie, I am always browsing online for articles that can help me. Thank you

I have been exploring for a little bit for any high quality articles or weblog posts in this kind of house . Exploring in Yahoo I eventually stumbled upon this site. Studying this info So i’m satisfied to express that I’ve a very excellent uncanny feeling I found out exactly what I needed. I so much surely will make certain to do not put out of your mind this website and provides it a glance regularly.

Hello! I know this is somewhat off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could locate a captcha plugin for my comment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having trouble finding one? Thanks a lot!

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read something like this before. So nice to search out someone with some authentic ideas on this subject. realy thanks for starting this up. this web site is one thing that is needed on the net, someone with just a little originality. useful job for bringing one thing new to the internet!

I have recently started a website, the information you offer on this website has helped me greatly. Thank you for all of your time & work.

You can definitely see your expertise within the paintings you write. The arena hopes for more passionate writers like you who aren’t afraid to mention how they believe. Always follow your heart.

Great wordpress blog here.. It’s hard to find quality writing like yours these days. I really appreciate people like you! take care

Heya i’m for the first time here. I found this board and I find It really useful & it helped me out much. I am hoping to give one thing back and help others such as you aided me.

Good day very nice web site!! Man .. Excellent .. Superb .. I will bookmark your website and take the feeds also?KI am satisfied to search out so many useful information here within the post, we’d like develop extra techniques on this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

You are a very bright individual!

Some truly nice and useful info on this internet site, besides I think the style and design holds good features.

Incredible! This blog looks exactly like my old one! It’s on a completely different topic but it has pretty much the same layout and design. Excellent choice of colors!

Hi there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found that it is truly informative. I’m gonna watch out for brussels. I will be grateful if you continue this in future. Lots of people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

You are my breathing in, I have few web logs and rarely run out from post :). “Truth springs from argument amongst friends.” by David Hume.

Good day very nice website!! Guy .. Excellent .. Wonderful .. I will bookmark your blog and take the feeds additionally?KI’m satisfied to seek out so many helpful info here in the publish, we want work out more strategies in this regard, thank you for sharing. . . . . .

Thanks for the update, is there any way I can get an update sent in an email every time you write a fresh post?

Terrific paintings! That is the kind of info that are meant to be shared across the net. Shame on Google for no longer positioning this publish upper! Come on over and consult with my web site . Thank you =)

You have brought up a very superb points, appreciate it for the post.

Superb blog! Do you have any suggestions for aspiring writers? I’m planning to start my own blog soon but I’m a little lost on everything. Would you propose starting with a free platform like WordPress or go for a paid option? There are so many options out there that I’m totally overwhelmed .. Any recommendations? Thanks a lot!

You have brought up a very excellent details, thankyou for the post.

Helpful information. Fortunate me I found your web site by chance, and I’m shocked why this twist of fate didn’t came about in advance! I bookmarked it.

You made some respectable factors there. I regarded on the internet for the difficulty and found most people will associate with together with your website.

It’s hard to find knowledgeable people on this topic, but you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

You can definitely see your skills in the work you write. The arena hopes for even more passionate writers such as you who aren’t afraid to say how they believe. Always follow your heart.

Very interesting points you have remarked, thanks for putting up. “‘Tis an ill wind that blows no minds.” by Malaclypse the Younger.

Greetings! Very helpful advice on this article! It is the little changes that make the biggest changes. Thanks a lot for sharing!

I was very pleased to find this web-site.I wanted to thanks for your time for this wonderful read!! I definitely enjoying every little bit of it and I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you blog post.

My brother suggested I might like this web site. He was totally right. This post actually made my day. You cann’t imagine just how much time I had spent for this information! Thanks!

good post.Ne’er knew this, thankyou for letting me know.

hello there and thank you for your information – I’ve certainly picked up anything new from right here. I did however expertise a few technical issues using this website, since I experienced to reload the site many times previous to I could get it to load properly. I had been wondering if your web hosting is OK? Not that I’m complaining, but sluggish loading instances times will very frequently affect your placement in google and could damage your high quality score if ads and marketing with Adwords. Well I’m adding this RSS to my email and can look out for much more of your respective intriguing content. Ensure that you update this again soon..

Keep up the wonderful piece of work, I read few posts on this web site and I think that your web blog is real interesting and holds sets of superb info .

Currently it sounds like BlogEngine is the top blogging platform available right now. (from what I’ve read) Is that what you are using on your blog?

The next time I read a blog, I hope that it doesnt disappoint me as much as this one. I mean, I know it was my choice to read, but I actually thought youd have something interesting to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about something that you could fix if you werent too busy looking for attention.

ResumeHead is a resume writing company that helps you get ahead in your career. We are a group of certified resume writers who have extensive knowledge and experience in various fields and industries. We know how to highlight your strengths, achievements, and potential in a way that attracts the attention of hiring managers and recruiters. We also offer other services such as cover letter writing, LinkedIn profile optimization, and career coaching. Whether you need a resume for a new job, a promotion, or a career change, we can help you create a resume that showcases your unique value proposition. Contact us today and let us help you get the resume you deserve.

Whoa! This blog looks exactly like my old one! It’s on a entirely different topic but it has pretty much the same page layout and design. Wonderful choice of colors!

Valuable information. Lucky me I found your site by accident, and I am shocked why this accident did not happened earlier! I bookmarked it.

It¦s really a nice and helpful piece of information. I¦m happy that you simply shared this useful info with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

Hey very cool blog!! Man .. Beautiful .. Amazing .. I’ll bookmark your website and take the feeds also…I’m happy to find numerous useful information here in the post, we need work out more techniques in this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

certainly like your web site but you have to check the spelling on several of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling issues and I to find it very bothersome to tell the truth nevertheless I’ll certainly come again again.

Yesterday, while I was at work, my sister stole my iPad and tested to see if it can survive a 40 foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My iPad is now destroyed and she has 83 views. I know this is totally off topic but I had to share it with someone!

I’ll right away seize your rss as I can not find your e-mail subscription hyperlink or newsletter service. Do you have any? Please let me know so that I may subscribe. Thanks.

I have been absent for some time, but now I remember why I used to love this website. Thanks, I will try and check back more often. How frequently you update your site?

Does your website have a contact page? I’m having problems locating it but, I’d like to shoot you an e-mail. I’ve got some creative ideas for your blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great site and I look forward to seeing it grow over time.

Very interesting information!Perfect just what I was searching for!

Just wanna input that you have a very nice site, I like the style it really stands out.

I’m impressed, I need to say. Really not often do I encounter a weblog that’s each educative and entertaining, and let me let you know, you will have hit the nail on the head. Your idea is excellent; the difficulty is one thing that not sufficient people are speaking intelligently about. I’m very pleased that I stumbled across this in my seek for one thing referring to this.

I’m not sure why but this website is loading incredibly slow for me. Is anyone else having this issue or is it a problem on my end? I’ll check back later on and see if the problem still exists.

I’m extremely impressed along with your writing talents as well as with the format for your blog. Is this a paid topic or did you customize it yourself? Anyway keep up the nice quality writing, it is uncommon to look a great blog like this one today..

I?¦m now not certain where you are getting your information, however good topic. I must spend a while finding out more or figuring out more. Thanks for fantastic information I used to be in search of this info for my mission.

I simply could not go away your website before suggesting that I actually loved the standard information an individual provide in your visitors? Is going to be again regularly in order to investigate cross-check new posts.

My brother recommended I would possibly like this blog. He was entirely right. This publish actually made my day. You can not believe simply how so much time I had spent for this info! Thanks!

Excellent weblog right here! Also your site so much up very fast! What host are you the usage of? Can I am getting your associate hyperlink for your host? I desire my web site loaded up as fast as yours lol

Nice read, I just passed this onto a friend who was doing a little research on that. And he just bought me lunch since I found it for him smile Thus let me rephrase that: Thank you for lunch!

I together with my pals were actually taking note of the nice information and facts found on your web site and then immediately I got a horrible feeling I never expressed respect to the website owner for those techniques. Most of the women came for this reason joyful to read through all of them and have now simply been taking pleasure in these things. I appreciate you for genuinely considerably thoughtful and then for getting this form of superior areas millions of individuals are really needing to discover. My sincere apologies for not expressing gratitude to you sooner.

Hey! Do you know if they make any plugins to protect against hackers? I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any recommendations?

Some truly good blog posts on this web site, thank you for contribution. “A man with a new idea is a crank — until the idea succeeds.” by Mark Twain.

After research a few of the weblog posts on your web site now, and I really like your method of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website listing and shall be checking back soon. Pls check out my web site as nicely and let me know what you think.

Great wordpress blog here.. It’s hard to find quality writing like yours these days. I really appreciate people like you! take care

Hello my friend! I want to say that this article is awesome, nice written and include approximately all important infos. I would like to see more posts like this.

Hello, i read your blog from time to time and i own a similar one and i was just wondering if you get a lot of spam remarks? If so how do you prevent it, any plugin or anything you can recommend? I get so much lately it’s driving me crazy so any help is very much appreciated.

Hello, Neat post. There’s an issue with your web site in web explorer, could check thisK IE still is the marketplace leader and a huge component of people will miss your excellent writing due to this problem.

Utterly written subject matter, thankyou for entropy.

It’s really a great and helpful piece of information. I’m glad that you shared this useful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

Do you have a spam problem on this site; I also am a blogger, and I was curious about your situation; many of us have developed some nice methods and we are looking to trade solutions with others, why not shoot me an email if interested.

Hi, i think that i saw you visited my website thus i came to “return the favor”.I am attempting to find things to improve my website!I suppose its ok to use some of your ideas!!

Hiya, I am really glad I have found this info. Today bloggers publish only about gossips and net and this is actually irritating. A good web site with exciting content, this is what I need. Thank you for keeping this website, I will be visiting it. Do you do newsletters? Cant find it.

Some genuinely interesting details you have written.Assisted me a lot, just what I was looking for : D.

Regards for this post, I am a big fan of this internet site would like to proceed updated.

Hmm is anyone else experiencing problems with the images on this blog loading? I’m trying to figure out if its a problem on my end or if it’s the blog. Any feed-back would be greatly appreciated.

very good post, i actually love this website, keep on it

Wow! This could be one particular of the most useful blogs We’ve ever arrive across on this subject. Actually Magnificent. I’m also a specialist in this topic therefore I can understand your effort.

Hello, i think that i saw you visited my website so i came to “return the favor”.I’m attempting to find things to improve my site!I suppose its ok to use some of your ideas!!

Hello there, I found your website via Google while looking for a related topic, your site came up, it looks good. I have bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

Great post, you have pointed out some wonderful details , I besides conceive this s a very great website.

I haven¦t checked in here for some time as I thought it was getting boring, but the last several posts are great quality so I guess I¦ll add you back to my everyday bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

Aw, this was a very nice post. In concept I would like to put in writing like this additionally – taking time and precise effort to make a very good article… however what can I say… I procrastinate alot and certainly not seem to get something done.

Usually I don’t read article on blogs, but I would like to say that this write-up very compelled me to try and do it! Your writing taste has been surprised me. Thanks, very great post.

Regards for this howling post, I am glad I noticed this internet site on yahoo.

Your style is so unique compared to many other people. Thank you for publishing when you have the opportunity,Guess I will just make this bookmarked.2

Ich war für einige Zeit abwesend gewesen, aber jetzt weiß ich wieder, warum ich diese Website geliebt habe. Danke, ich werde versuchen, oft öfter vorbeizuschauen. Wie oft aktualisieren Sie Ihre website?

Hi, Neat post. There is a problem with your site in internet explorer, would check this… IE still is the market leader and a good portion of people will miss your excellent writing due to this problem.

Hmm is anyone else encountering problems with the pictures on this blog loading? I’m trying to determine if its a problem on my end or if it’s the blog. Any feedback would be greatly appreciated.

You have observed very interesting points! ps nice site. “I just wish we knew a little less about his urethra and a little more about his arms sales to Iran.” by Andrew A. Rooney.

I?¦ll immediately clutch your rss feed as I can not in finding your e-mail subscription hyperlink or newsletter service. Do you have any? Kindly permit me know so that I could subscribe. Thanks.

Deference to article author, some great selective information.

I got what you mean , appreciate it for posting.Woh I am glad to find this website through google.

I know this if off topic but I’m looking into starting my own weblog and was wondering what all is required to get set up? I’m assuming having a blog like yours would cost a pretty penny? I’m not very web savvy so I’m not 100 positive. Any suggestions or advice would be greatly appreciated. Thank you

Heya i’m for the first time here. I found this board and I in finding It really helpful & it helped me out much. I hope to offer one thing again and help others such as you helped me.

Hi, I think your site might be having browser compatibility issues. When I look at your website in Safari, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, fantastic blog!

Only a smiling visitor here to share the love (:, btw great style and design. “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not one bit simpler.” by Albert Einstein.

Thanks for some other magnificent article. Where else may anybody get that type of info in such a perfect way of writing? I’ve a presentation subsequent week, and I’m at the search for such info.

Some really good posts on this site, appreciate it for contribution.

It’s in point of fact a great and useful piece of information. I am satisfied that you simply shared this helpful information with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

I like this blog its a master peace ! Glad I observed this on google .

I would like to thnkx for the efforts you have put in writing this blog. I am hoping the same high-grade blog post from you in the upcoming as well. In fact your creative writing abilities has inspired me to get my own blog now. Really the blogging is spreading its wings quickly. Your write up is a good example of it.

Wonderful beat ! I wish to apprentice while you amend your site, how can i subscribe for a blog site? The account aided me a acceptable deal. I had been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast provided bright clear idea

I really like your writing style, excellent info , thanks for posting : D.

This really answered my problem, thank you!

You made a few good points there. I did a search on the subject matter and found nearly all persons will go along with with your blog.

This is the right blog for anyone who wants to find out about this topic. You realize so much its almost hard to argue with you (not that I actually would want…HaHa). You definitely put a new spin on a topic thats been written about for years. Great stuff, just great!

you’re really a excellent webmaster. The web site loading pace is amazing. It seems that you are doing any unique trick. Moreover, The contents are masterwork. you’ve performed a magnificent job on this subject!

What¦s Going down i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve discovered It absolutely useful and it has helped me out loads. I’m hoping to give a contribution & aid other users like its aided me. Good job.

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read anything like this before. So good to seek out somebody with some original thoughts on this subject. realy thank you for starting this up. this web site is something that’s wanted on the internet, somebody with somewhat originality. useful job for bringing something new to the web!

You are my breathing in, I possess few blogs and infrequently run out from to post : (.

Very interesting details you have mentioned, appreciate it for posting. “Brass bands are all very well in their place – outdoors and several miles away.” by Sir Thomas Beecham.

What¦s Going down i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve discovered It positively helpful and it has aided me out loads. I’m hoping to contribute & assist different customers like its helped me. Great job.

Hello there! This post could not be written any better! Reading this post reminds me of my good old room mate! He always kept talking about this. I will forward this write-up to him. Fairly certain he will have a good read. Many thanks for sharing!

Thank you for the sensible critique. Me and my neighbor were just preparing to do some research about this. We got a grab a book from our local library but I think I learned more clear from this post. I am very glad to see such magnificent information being shared freely out there.

Enjoyed studying this, very good stuff, appreciate it. “All things are difficult before they are easy.” by John Norley.

Yeah bookmaking this wasn’t a high risk conclusion outstanding post! .

F*ckin’ tremendous things here. I am very glad to peer your post. Thank you a lot and i’m having a look forward to contact you. Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?

Fantastic site. Lots of useful information here. I?¦m sending it to a few friends ans also sharing in delicious. And of course, thank you to your sweat!

As soon as I noticed this web site I went on reddit to share some of the love with them.

Whats Going down i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I have found It absolutely helpful and it has aided me out loads. I hope to contribute & assist other customers like its aided me. Great job.

My partner and I absolutely love your blog and find a lot of your post’s to be what precisely I’m looking for. Would you offer guest writers to write content available for you? I wouldn’t mind publishing a post or elaborating on a number of the subjects you write with regards to here. Again, awesome web log!

You are a very clever individual!

Just wanna remark on few general things, The website layout is perfect, the written content is very great : D.

Thanks for helping out, good info. “A man will fight harder for his interests than for his rights.” by Napoleon Bonaparte.

Good day! This is kind of off topic but I need some guidance from an established blog. Is it tough to set up your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out pretty fast. I’m thinking about setting up my own but I’m not sure where to start. Do you have any ideas or suggestions? Cheers

There may be noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain nice points in options also.

obviously like your web site however you have to take a look at the spelling on several of your posts. Several of them are rife with spelling issues and I to find it very troublesome to tell the truth however I¦ll surely come again again.

Hi there! This post couldn’t be written any better! Reading through this post reminds me of my previous room mate! He always kept talking about this. I will forward this article to him. Pretty sure he will have a good read. Thank you for sharing!

Howdy! This is kind of off topic but I need some help from an established blog. Is it difficult to set up your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out pretty quick. I’m thinking about creating my own but I’m not sure where to begin. Do you have any ideas or suggestions? Appreciate it

Hello, Neat post. There’s a problem together with your web site in internet explorer, may check this?K IE still is the market chief and a good component of other folks will miss your wonderful writing due to this problem.

It’s truly a great and helpful piece of info. I am glad that you shared this helpful information with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

It?¦s in reality a nice and helpful piece of information. I am glad that you simply shared this useful information with us. Please stay us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

I like the efforts you have put in this, thankyou for all the great blog posts.

Just desire to say your article is as astounding. The clearness in your post is just cool and i can assume you are an expert on this subject. Fine with your permission let me to grab your RSS feed to keep up to date with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please carry on the gratifying work.

Hi, I think your site might be having browser compatibility issues. When I look at your website in Safari, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, fantastic blog!

There are some interesting time limits in this article but I don’t know if I see all of them heart to heart. There is some validity but I will take hold opinion until I look into it further. Good article , thanks and we wish extra! Added to FeedBurner as properly

Pretty nice post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and wished to say that I have truly loved browsing your weblog posts. In any case I will be subscribing to your rss feed and I am hoping you write again soon!

There’s noticeably a bundle to learn about this. I assume you made sure nice points in features also.

I like what you guys are up also. Such smart work and reporting! Keep up the excellent works guys I have incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it will improve the value of my web site :).

Hey there! This is kind of off topic but I need some advice from an established blog. Is it very difficult to set up your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out pretty fast. I’m thinking about creating my own but I’m not sure where to begin. Do you have any points or suggestions? Thanks

It is actually a great and helpful piece of info. I am glad that you just shared this helpful information with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

Good site! I truly love how it is easy on my eyes and the data are well written. I’m wondering how I might be notified whenever a new post has been made. I have subscribed to your RSS which must do the trick! Have a great day!

Greetings! Very helpful advice on this article! It is the little changes that make the biggest changes. Thanks a lot for sharing!

I have been checking out some of your articles and it’s nice stuff. I will make sure to bookmark your site.

I real pleased to find this internet site on bing, just what I was looking for : D also saved to my bookmarks.

Thank you for the sensible critique. Me & my neighbor were just preparing to do a little research about this. We got a grab a book from our local library but I think I learned more clear from this post. I’m very glad to see such magnificent information being shared freely out there.

I very glad to find this internet site on bing, just what I was looking for : D also saved to my bookmarks.

I got what you mean , thanks for putting up.Woh I am glad to find this website through google. “Delay is preferable to error.” by Thomas Jefferson.

I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you create this website yourself or did you hire someone to do it for you? Plz reply as I’m looking to create my own blog and would like to find out where u got this from. many thanks

You are a very smart individual!

Perfect work you have done, this internet site is really cool with superb information.

There is evidently a lot to know about this. I believe you made various good points in features also.

Excellent blog right here! Additionally your web site so much up very fast! What host are you the use of? Can I am getting your affiliate link on your host? I wish my site loaded up as fast as yours lol

Oh my goodness! an amazing article dude. Thanks However I’m experiencing concern with ur rss . Don’t know why Unable to subscribe to it. Is there anyone getting an identical rss problem? Anybody who is aware of kindly respond. Thnkx

Saved as a favorite, I really like your blog!

hello!,I like your writing very so much! share we communicate more approximately your post on AOL? I require a specialist in this area to resolve my problem. May be that’s you! Taking a look forward to look you.

Wow that was strange. I just wrote an extremely long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Anyway, just wanted to say superb blog!

Heya i’m for the primary time here. I came across this board and I find It really useful & it helped me out much. I am hoping to present one thing back and help others such as you helped me.

I want to express appreciation to the writer for rescuing me from this type of circumstance. Right after looking through the world wide web and obtaining things which are not pleasant, I was thinking my life was gone. Existing without the presence of solutions to the problems you’ve resolved through your good report is a serious case, and those that could have badly affected my career if I had not come across your blog. The natural talent and kindness in dealing with every part was vital. I am not sure what I would’ve done if I hadn’t come upon such a solution like this. I can also at this time look forward to my future. Thanks for your time so much for the skilled and effective help. I won’t think twice to refer your web sites to anyone who ought to have guidance about this matter.

Your style is so unique compared to many other people. Thank you for publishing when you have the opportunity,Guess I will just make this bookmarked.2

I like what you guys tend to be up too. This type of clever work and coverage! Keep up the fantastic works guys I’ve added you guys to my own blogroll.

Very interesting info !Perfect just what I was searching for!

I really appreciate this post. I’ve been looking all over for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You’ve made my day! Thanks again

I have been browsing on-line greater than 3 hours these days, yet I by no means found any interesting article like yours. It?¦s beautiful value enough for me. In my view, if all site owners and bloggers made good content material as you did, the net shall be a lot more useful than ever before.

Your style is so unique compared to many other people. Thank you for publishing when you have the opportunity,Guess I will just make this bookmarked.2

Hi there, just became alert to your blog through Google, and found that it is really informative. I’m gonna watch out for brussels. I’ll appreciate if you continue this in future. Many people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

Wow, fantastic blog layout! How long have you been blogging for? you made blogging look easy. The overall look of your website is great, as well as the content!

Well I truly enjoyed studying it. This article procured by you is very constructive for good planning.

Real excellent info can be found on site.

Its wonderful as your other articles : D, thanks for putting up.

I was more than happy to find this net-site.I needed to thanks for your time for this glorious learn!! I positively having fun with every little little bit of it and I’ve you bookmarked to check out new stuff you blog post.

I am always looking online for tips that can aid me. Thanks!

What is FitSpresso? FitSpresso, a dietary supplement presented in pill form, offers a comprehensive approach to weight loss by enhancing metabolism and augmenting the body’s fat-burning capacity

I have been exploring for a little bit for any high-quality articles or blog posts in this kind of area . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this website. Reading this info So i am glad to exhibit that I’ve a very excellent uncanny feeling I came upon just what I needed. I most unquestionably will make sure to don¦t fail to remember this web site and provides it a glance on a continuing basis.

What is FitSpresso? FitSpresso, a dietary supplement presented in pill form, offers a comprehensive approach to weight loss by enhancing metabolism and augmenting the body’s fat-burning capacity

Some really nice and useful info on this web site, as well I conceive the design and style contains wonderful features.

Hey! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a team of volunteers and starting a new initiative in a community in the same niche. Your blog provided us valuable information to work on. You have done a outstanding job!

What Is Puravive? Puravive is a natural formula that supports healthy weight loss. This supplement helps to ignite the levels of brown adipose tissue in the body to lose extra weight

Unbestreitbar glauben Sie, was Sie ausgesagt. Ihr Lieblings-Begründungsgrund schien im Internet die einfachste Sache zu sein, die man kennen muss. Ich sage Ihnen, es ärgert mich auf jeden Fall, wenn Menschen über Sorgen nachdenken, von denen sie einfach nichts wissen. Sie haben es geschafft, den Nagel auf den Punkt zu treffen und das Ganze zu definieren, ohne Nebenwirkungen zu haben, die Leute können ein Zeichen nehmen. Werde wahrscheinlich wiederkommen, um mehr zu bekommen. Danke

Nice blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere? A theme like yours with a few simple tweeks would really make my blog jump out. Please let me know where you got your theme. Bless you

What Is Tonic Greens? Tonic Greens is a wellness aid that helps with combatting herpes in addition to enhancing your well-being.

so much good information on here, : D.

Hi would you mind letting me know which web host you’re using? I’ve loaded your blog in 3 completely different internet browsers and I must say this blog loads a lot faster then most. Can you recommend a good web hosting provider at a reasonable price? Thanks a lot, I appreciate it!

Hey I am so happy I found your blog, I really found you by accident, while I was browsing on Askjeeve for something else, Nonetheless I am here now and would just like to say many thanks for a marvelous post and a all round thrilling blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to read through it all at the minute but I have bookmarked it and also added your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read more, Please do keep up the superb job.

What Is Tonic Greens? Tonic Greens is a wellness aid that helps with combatting herpes in addition to enhancing your well-being

Wow, incredible blog layout! How long have you been blogging for? you make blogging look easy. The overall look of your web site is excellent, as well as the content!

Do you have a spam issue on this website; I also am a blogger, and I was wanting to know your situation; many of us have created some nice methods and we are looking to swap strategies with other folks, why not shoot me an e-mail if interested.

You are a very smart person!

Lovely just what I was searching for.Thanks to the author for taking his time on this one.

Hey there would you mind sharing which blog platform you’re using? I’m planning to start my own blog soon but I’m having a hard time selecting between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal. The reason I ask is because your design and style seems different then most blogs and I’m looking for something completely unique. P.S My apologies for being off-topic but I had to ask!

great points altogether, you simply gained a brand new reader. What would you recommend in regards to your post that you made a few days ago? Any positive?

I have not checked in here for some time since I thought it was getting boring, but the last several posts are good quality so I guess I will add you back to my everyday bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

Usually I don’t learn post on blogs, however I wish to say that this write-up very forced me to take a look at and do it! Your writing style has been surprised me. Thank you, very great post.

Hmm is anyone else having problems with the pictures on this blog loading? I’m trying to determine if its a problem on my end or if it’s the blog. Any responses would be greatly appreciated.