[intro]Moses Tladi is considered one of South Africa’s first black landscape artists to have his work exhibited around the country. The self-taught Tladi’s talent as a landscape painter flourished in the 1920s and 1930s; he left behind roughly 40 works. His paintings are as colourful and peaceful as they are rough and emotive, and through his landscapes we come to understand a man whose life was tied up with the politics of the time. Swept from his home with the wave of migrant labour to the city of Johannesburg, having his works exhibited at ‘whites-only’ galleries that he often could not enter by law, and victim to the forced removals of 1956; his talent did not exempt him from the inequalities facing black South Africans at the time. A recently released documentary, titled Moses Tladi Unearthed, explores his journey as an artist, and his work is currently being exhibited at the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town.[/intro]

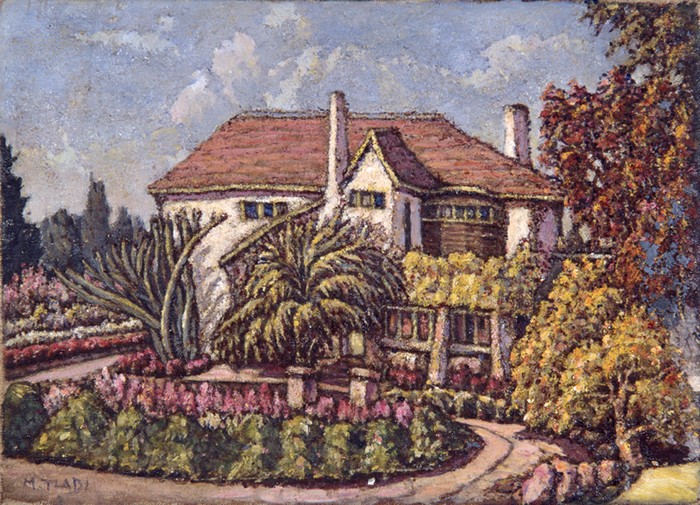

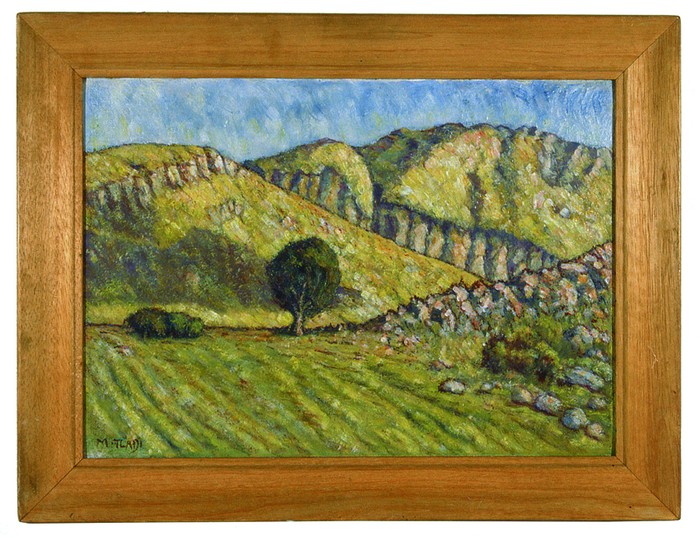

Tladi’s oil paintings are small and intimate. His colour palette was subtle and understated, but one of his greatest skills was incorporating scattered hues, less visible to the naked eye, which imbued his work with rich atmospheric effects and romantic undertones.

Tladi was one of the first black artists to exhibit at the South African National Gallery, a largely untrained artist, his oeuvre exists as a record of his thoughts, experiences and the beauty of the landscape that surrounded him as he travelled, including the hills and mountains of Sekhukhuneland, Driefontein and Magaliesberg.

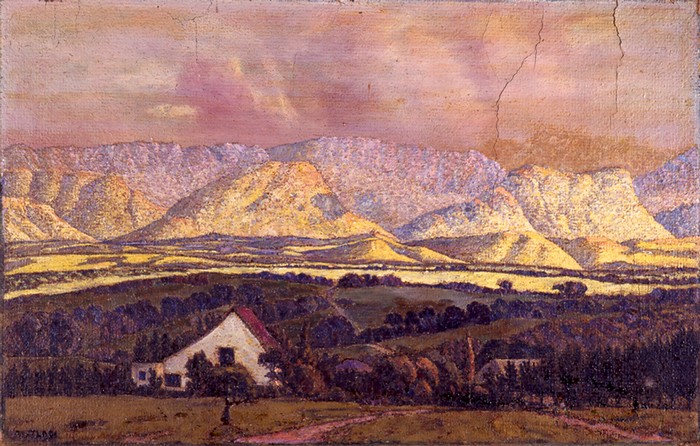

Lanscape

His usually small, yet visible, brushstrokes often captured the movement of wind through the leaves of trees and alluded to the fleeting qualities of nature. The mountain ranges depicted in his work would hint at the sublimity of nature. His love for trees is apparent and he often used trees as a compositional device, either framing the landscape scenery or using them as a centerpiece. The image of a path or road also reoccurs in his works, used as a method to lead the eye into the picture and take the viewer on an imagined journey. He was also sensitive to the accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities due to time of day or season in his artistic practice.

Tladi did not receive any formal art education. It is thought that he may have had some formal training, at a later stage, either at the ‘Bantu’ School of Arts or at Polly Street Centre. However, he had a keen and instinctive observational skill and closely studied the work of other artists. He was especially drawn to artworks such as Le Printemps by Claude Monet (1840-1926) and The Last Days of Summer by Henri-Joseph Harpiginies (1819-1916).

Both Monet and Harpignies were known for their plein-air landscapes. En plein air (‘in the open air’) is used to describe the act of painting outdoors. In many ways, Tladi was also a plein-air painter. He captured as meticulously as possible the mood of the natural scenes around him, straddling both realism and imagination in his work.

Curator of Historical Paintings and Sculpture at Iziko Art Collections, Hayden Proud, suggests:

…in looking at primarily the landscapes of Moses Tladi, one can sense that he was looking very hard at the work of other artists such as Pierneef, Volschenk and many others. But there is a kind of sincerity and a kind of integrity to the work. That kind of painting – the sincerity, that honesty and directness of vision and expression that is so individual to certain artists is something that gives his work a kind of quality that is unpretentious. It’s got a sort of solid earthy integrity to it, which I think is quite unique; certainly for an artist – a black artist – working at that time.

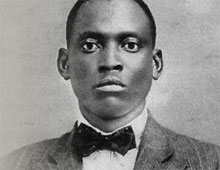

Moses Tladi was born in 1903 in the remote Sekhukhuneland, in what is today the Limpopo Province. He was raised in a traditional Pedi family by his father Selaoane, a local traditional healer, who made his living working with iron, and his mother Rekiloe, a gifted potter. His early years were spent herding cattle surrounded by hills and peaks.

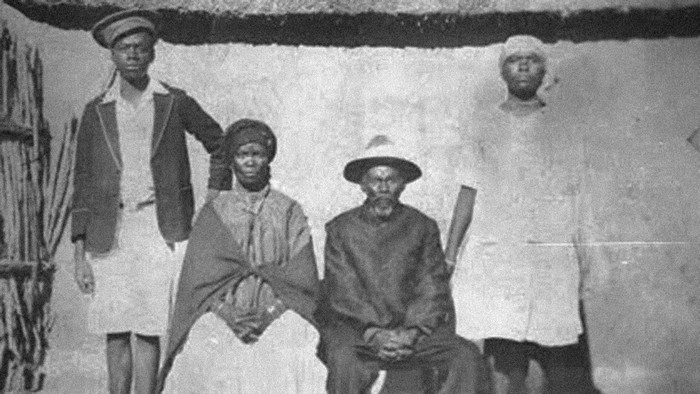

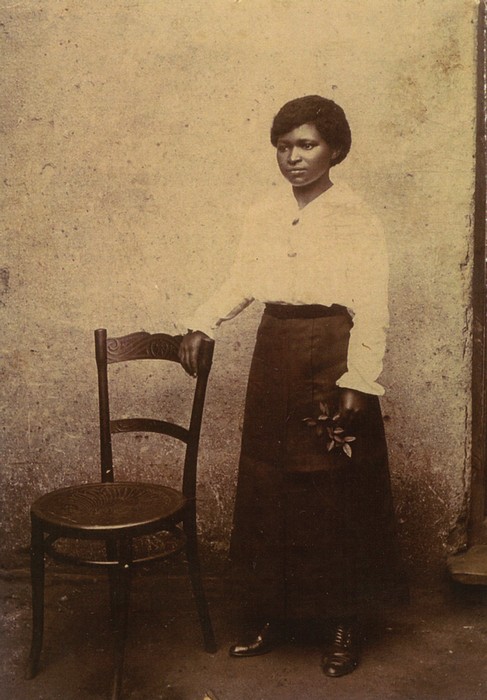

Moses Tladi’s Parents

Under the influence of the Berlin Missionary Society, Tladi’s parents converted to Christianity and Moses was educated at the Lobethal mission school. Their lives were deeply affected by the violent expansion of the colonial government, which sought to segregate, and dispossess black people of their land.

Herbert Read

The Land Act of 1913 denied black South Africans land ownership outside the small ‘native’ reserves. The act legitimised systemic land dispossession and created a cheap itinerant labour force for the mines. It laid the foundation of Apartheid, formally legislated in 1948. Many migrant workers ended up as miners, but Tladi found work as a gardener for Herbert Read (1875-1942) at his house, Lokshoek, in Parktown. This is where he began his life as an artist.

Lokshoek Joahnnesburg

When he started painting with leftover commercial house paint and a stick, Tladi’s nascent talent as an artist was recognised by his employer, Read, who provided him with artists’ materials; as well as the use of a carriage house to pursue his painting. Read encouraged him to paint the garden at Lokshoek. Tladi’s daughter, Mmapula Tladi, recalls the legend:

The story goes that that’s where he started his painting career. The family children found him one day in the garden using bits of paper…discarded paper that he could find; Bits of discarded pencils, drawing. And they told their father about this, Herbert Read, who then seeing what my father was able to do, got him some papers and pens and so forth.

Read also introduced Tladi to the one-time mayor of Johannesburg and philanthropist, Howard Pim. He played a leading role in the establishment of the Johannesburg Art Gallery and it was he who introduced Tladi to the gallery environment, and promoted his work at public exhibitions in the late 1920s.

Life was tough for black artists in South Africa, their talent was rarely recognised; and if they were invited to exhibit their art, many of the ‘whites-only’ galleries would not have allowed black artists to view their own work.

Despite the barrier to entry, based entirely on his race, Tladi participated, for the first time, in the Tenth Annual Exhibition of the South Africa Academy in 1929, held at the Selborne Hall in Johannesburg, within a section titled the ‘Special Exhibition by Native Artist’. He is also mentioned in the catalogue of the First Annual Exhibition of Contemporary National Art, staged in co-operation with the South African Society of Artists (SASA) at the South African National Gallery in 1931. In this exhibition, Tladi exhibited his Witwatersrand Winter and Spring, which were priced at 4 and 3 guineas each. He probably did not see this show in person.

Manako Sekhukuniland

At the Grahamstown Arts and Craft Festival Exhibition in March 1932, Tladi won the first and second prizes in the open section for landscape and seascape painting. Landscape with Trees, which won the second prize, is now housed at Museum Africa in Johannesburg.

Tladi also featured in the 1933 annual exhibition at the South African National Gallery, showing Manako Sekhukuniland (sic) and the now-lost Winter near Mooikraal. In 1938, he held his first solo exhibition at Swedish Hall in Johannesburg. A year later, the artist participated in an exhibition at the South African Academy and in an exhibition at Gainsborough Galleries.

Sekhubami

Tladi married Sekhubami More in 1931; his wife was born in 1899 in Heidelberg, and died in 1981. Together, they had four children: Rekiloe (1931 – 2014), Selaoane (1934 – 1981), Mmapula (b. 1936) and Ramotebele (b.1942). His family originally lived in Sophiatown before he built them a home in Kensington B, near Ferndale.

The House in Kensington B

Tladi served during the Second World War and was stationed at Kroonstad in the Free State. On his return to Johannesburg he continued to paint until the heartbreaking events of 1956 when he and his family were forced to move out of their home due to the ‘urban removals’ enforced as a result of the Nationalist government’s apartheid policy. Mmapula Tladi reflects:

…that was the deal and we were to move. He had grown a wonderful orchard in Kensington B and some Jacaranda trees which turned out to be our playground. And I remember my father took an axe, went into the orchard and he chopped and chopped…it was a big orchard…in the end I decided, this is dangerous, I better help. And together we chopped and chopped. He was silent through all of it. It took days, but every day he got up and chopped a tree. From the day my father was moving from Kensington B, he never ever picked up a brush. That was it.

Despite flourishing in the 1930s, gaining public attention and prizes, he did not pick up a paintbrush again and his life ended tragically in 1959.

Morning at Magaliesberg Mountains

In recent times, with the arrival of South Africa’s new democracy, the work of this artist has begun to resurface. Some of his work was selected for the Land and Lives exhibition at the Johannesburg Art Gallery in 1997. Angela Lloyd Read, the granddaughter of Herbert Read, published a book on the artist – The Artist in the Garden: The Quest for Moses Tladi in 2010, and there was also an exhibition on his work at the South African House in London in that year.

His works are currently being exhibited at the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town. The show is running until May and will then move to Grahamstown.