Percy Mabandu

The events of 21 March 1960 in Sharpeville forced South Africa’s artists to create work that responded to the political moment. Many used their creativity to bolster the liberation movement.

Apartheid police shot and killed 69 pass law protesters and injured 180 more on 21 March 1960. The Sharpeville massacre was more than the wanton murder of unarmed demonstrators – most of whom were shot in the back as they ran for safety. It was also a turning point in the story of South Africa’s fight for freedom, and it unleashed a generation of artists driven to express their moral outrage.

21 March 1960: The Sharpeville massacre claimed the lives of 69 Black protesters who were among thousands demonstrating against the pass laws at the local police station. (Photograph by Universal History Archive/ UIG via Getty images)

The killing and responses to it ignited a long-running debate at the heart of which was the question of artistic participation in the struggle against apartheid. The African-Scandinavian Writers’ Conference in Stockholm in 1967 and the Culture & Resistance Conference in Gaborone in 1982 were among the gatherings that hosted discussions aimed at answering the question of how art can function as protest within the context of political repression. Albie Sachs’ historic paper Preparing Ourselves for Freedom, which explores the place of art in a free South Africa, also has its roots in the debates after Sharpeville.

Artists, musicians and writers differed on what they believed an appropriate response ought to be, but either way, the Sharpeville massacre had a lasting effect on all their lives and careers. Musicians such as Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela and members of The Blue Notes were forced into exile, while the work of artists such as Gerard Sekoto, Dumile Feni and others took on a decidedly anti-apartheid posture. Dennis Brutus, Nadine Gordimer and Keorapetse Kgositsile would increasingly see their writing lives as inseparable from their work as freedom fighters or activists.

Literary responses

South African literature already had a longstanding tradition of writers taking a stance against the colonial state when the massacre took place. This includes the work of Sol Plaatje, the first secretary general of the African National Congress (ANC), and journalists reporting on the horrors of apartheid during the 1950s – known as the Sophiatown Renaissance or the Drum decade – in publications such as Drum, New Age and The World.

Gordimer, who later received the Nobel Prize for Literature, spoke about how the massacre, along with the arrest of her best friend and trade unionist Bettie du Toit, were twin events that spurred her entry into the anti-apartheid movement. Gordimer helped to edit the speech Nelson Mandela gave in the dock as a defendant in the 1964 Rivonia Trial, in which he famously said, “[A democratic and free society] … is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

After Sharpeville, the first wave of young members of the ANC was instructed to leave the country. Among them was poet Kerapetse Kgositsile, who would later say that “the task facing artists is formidable… There are a number of charlatans, pimps and prostitutes running around the world masquerading as artists, talking about how sensitive they are, how they cannot be involved in social issues, how art is for its own sake and a lot of other nonsense.” To Kgositsile and others, such as fellow poet Dennis Brutus, art and the fight for freedom were one.

Brutus, who was arrested, banned and imprisoned many times before heading into exile, published his first anthology, Sirens, Knuckles and Boots in 1963 while in prison. His most enduring response to the massacre is the poem Sharpeville published in his collection Stubborn Hope (1978). In it he writes, “Remember Sharpeville / Remember bullet-in-the-back day / And remember the unquenchable will for freedom / Remember the dead and be glad”.

Other figures from the South African literary landscape responded differently. Lewis Nkosi insisted on a necessary separation between what people did as artists and how they acted as citizens committed to human rights.

Seven years after the massacre, Nkosi presented a paper on Individualism and Social Commitment at a writers’ conference in Stockholm. He wrote: “We cannot judge how good the poet Dennis Brutus is by simply counting the number of guns he has carried to the revolutionary front. This question lies outside literary considerations, as at least I see them. It is the kind of question that can sensibly be put to the writer as a man, as a citizen … the reason [writers] think they have a special function to perform in revolutionary situations is that they want to be excused from precisely those duties which other members of society are reluctantly performing … By writing bad committed poems, they suppose they have discharged their [revolutionary] duties. Of course, this is absurd – any social commitment that a writer has to his society is as a man, but the commitment of a writer as an artist is to a special kind of republic, the republic of letters.”

Nkosi left the country on an exit permit in 1960 after the events at Sharpeville. He was a critic, academic and novelist whose model of engagement with the social and artistic ramifications of the massacre and apartheid’s protracted brutality many have mirrored and espoused.

Music’s engagement

Before Sharpeville, singer and fledgling actress Makeba had not been overtly political in her work. But the events of 1960 irrevocably pushed her into the service of the liberation movement. Makeba first left the country in 1959 to promote the film Come Back, Africa at the Venice Film Festival. She would not be allowed to come home. She took refuge in London before settling in New York where she spoke out against apartheid at the United Nations in 1963.

Though she was publicly against minority rule in South Africa, it was not until the release of The Voice of Africa, her fourth record as a solo artist in 1964, in a song titled Mayibuye, that she called on Africans to take up the fight for freedom.

Makeba was one of the first musicians to go into exile, but she was followed by many others, including a then 21-year-old Masekela. The young trumpeter left soon after the massacre, also quickly becoming more politically vocal. His debut record in 1962, Trumpet Africaine: The New Beat from South Africa, included a track Magwalandini, which loosely means, “You cowards, you!” It is derived from a traditional nguni song Zemk’ Inkomo Magwalandini, which calls on young men to defend cows against thieves. As a metaphor, it plays into the African cattle complex, the knowledge field or folklore that uses cattle as central instruments in the negotiation of communal meaning.

Magwalandini is a call to arms by the newly exiled young man who would not return home until the ruling government was changed. It took 30 years.

Makeba and Masekela were connected to the many artists who performed in the hit musical King Kong and who used its success and tour of Europe as a way to go into exile after the rise in repression in the 1960s. They would become ambassadors of the freedom struggle across the world.

A visual approach

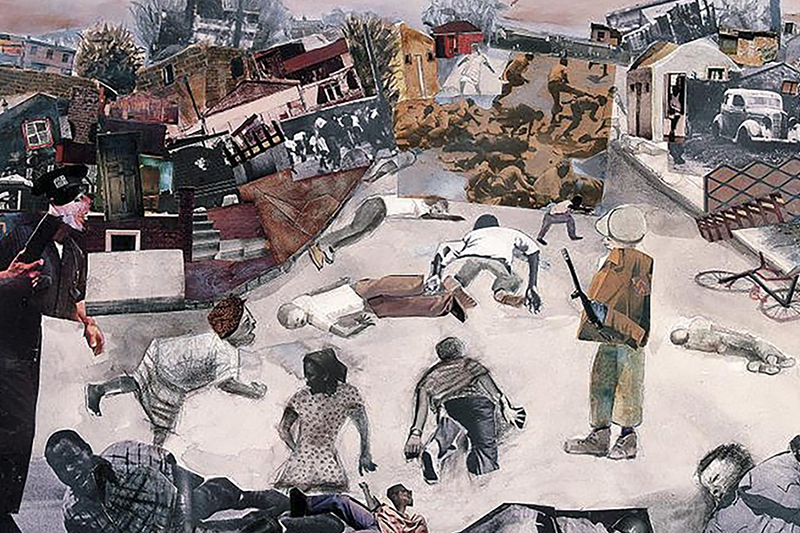

Artist Sam Nhlengethwa painted Sharpeville Shooting in 1992. He was five years old when the massacre took place. (Copyright © Campbell Smith Collection 2015)

As news of Sharpeville spread, a global network of activists was spurred into action. In Sweden, a committee for the advancement of African art and craft was formed in 1961. This led Peder and Ulla Gowenius to start the Art and Craft Centre at the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Rorke’s Drift, Natal in 1962. The centre would be central to the development of the careers of notable modern African artists. Much of what we consider the printmaking tradition in the country – including the work of artists such as John Muafangejo, Azaria Mbatha, Eric Mbatha, Dan Rakgoathe and Cyprian Shilakoe – is rooted in Rorke’s Drift.

Painter Sekoto, who had been exiled in Paris for 12 years by the time of the massacre, marked the moment with nine watercolour paintings on paper. He titled the series Recollections of Sharpeville. The work is in the Iziko South African National Gallery collection in Cape Town.

Later generations of visual artists are still going back to Sharpeville. Sam Nhlengethwa, who was five years old on the historic day, has returned to the massacre more than once, in a 1992 watercolour, Sharpeville Shooting, and a 2003 photolithograph and collage, Sharpeville Massacre.

Artistic renderings of the events at Sharpeville are unforgettable in part because of how they highlight the brutality of apartheid and the sacrifices made for democracy, but also because they remind us of other massacres: Boipatong, Bisho, Marikana.

(This article first appeared in New Frame)