[intro]There is nothing like a spell of travel to get to know someone. People drop their guard when they are far away from home. Journalist Sylvia Vollenhoven’s journeys with Mama Winnie went to places as diverse as Lusaka, Stockholm and Beijing, passing by Dar es Salaam along the way. She shares some of her insights.[/intro]

This article first appeared in City Press.

Winnie Mandela slaps an imaginary pistol on the table. The smack of her flat hand on the wood reverberates across the empty Chinese restaurant. “I would shoot her as she walks through the door,” she says. I flinch as if a gunshot has been fired. The conversation becomes one of those things I do not write about, especially as she is referring to Zindzi.

But the context for the conversation about shooting her beloved younger daughter is all important. How did we get to imaginings of filicide on an autumn afternoon in Beijing? Even in death Winnie Madikizela-Mandela stands tall on a mountain of complexity. So, if we wish to understand her we have to explore the many layers.

I explore Ma Winnie in the ways I know best. My own experiences, others who knew her, books and photographs.

Nomzamo Winifred Zanyiwe Madikizela was born in the spring of 1936 in the village of Bizana in the Transkei. It is an upbringing that puts in place the basic building blocks of her formidable personality.

By the time I meet Winnie I feel I know her although I’ve read hardly anything about her in the mainstream media. Several of my activist friends are the sons and daughters of the political elite of the Eastern Cape. They tell me endless stories about her. The tougher the official blackout on news about her, the faster the legends of her bravery spread.

I am a foreign correspondent seeking her out soon after her return from her banishment to Brandfort in the mid 1980s. One day there is a contingent of journalists following her as she drives to her home in Soweto where she has not been allowed to live for almost a decade. A police car blocks the way. She gets out, shouts at the police, punches a cop and continues driving to her home. The stuff of legend.

Compared to the media frenzy of subsequent decades there are relatively few journalists following her around in the mid 80s. Some of us develop a relationship with her that is underpinned by the common experience of bearing the brunt of apartheid. A cosiness we don’t care to discuss much.

By the time Nelson Mandela is released in 1990 Winnie and I have built up a trust that gives me unparalleled access to her husband. His attitude at the time is; “Any friend of Winnie’s…”

After his release the little house in Vilakazi Street becomes a media hub. On Madiba’s very first night home I leave the house late. He has long since gone to bed and Winnie is holding court.

The next day one of my colleagues who has been doing the obligatory stakeout all night for hungry foreign news outlets tells me Dali Mpofu, Winnie’s lover at the time, left at around 2am.

“And… Winnie left with him,” she says.

We decide that is not a story for now.

On their first trip overseas a few weeks later an airline ground stewardess assumes I am a relative and sells me the seat next to the Mandelas. I have found out that the flight starts in sleepy Lilongwe in Malawi so I begin my journey there. When the couple join the flight in Dar es Salaam I am already on board.

Seeing me Winnie says:

“How on earth did you manage to be on this plane ahead of us? Only you could do something like this.” She turns to her husband who has been waving at the crowds, “Look who’s here. What a pleasant surprise.”

For a while there is such fussing about Madiba from the KLM staff that we don’t say much to each other. She is sitting next to the window and I am on the aisle seat with Madiba between us.

Later the three of us talk for a while. Then Madiba asks for a second blanket, puts in his ear plugs, dons the mask from the goodie bag and does the genteel first class recline.

I get ready to sleep but Winnie wants to carry on the conversation. I am uncomfortable because she has to raise her voice above the hum of the engines.

“Where did you board this plane? How did you manage to get a seat next to us?”

I answer tersely then point at Madiba, with a gesture of discomfort.

“Oh don’t mind him, he sleeps through anything.”

The dismissive wave of the hand helps me get over my hero worship. A few days later in Stockholm — Madiba is making a point of first visiting the nations who supported most strongly our struggle against apartheid — I am rewarded for keeping her company during the long night.

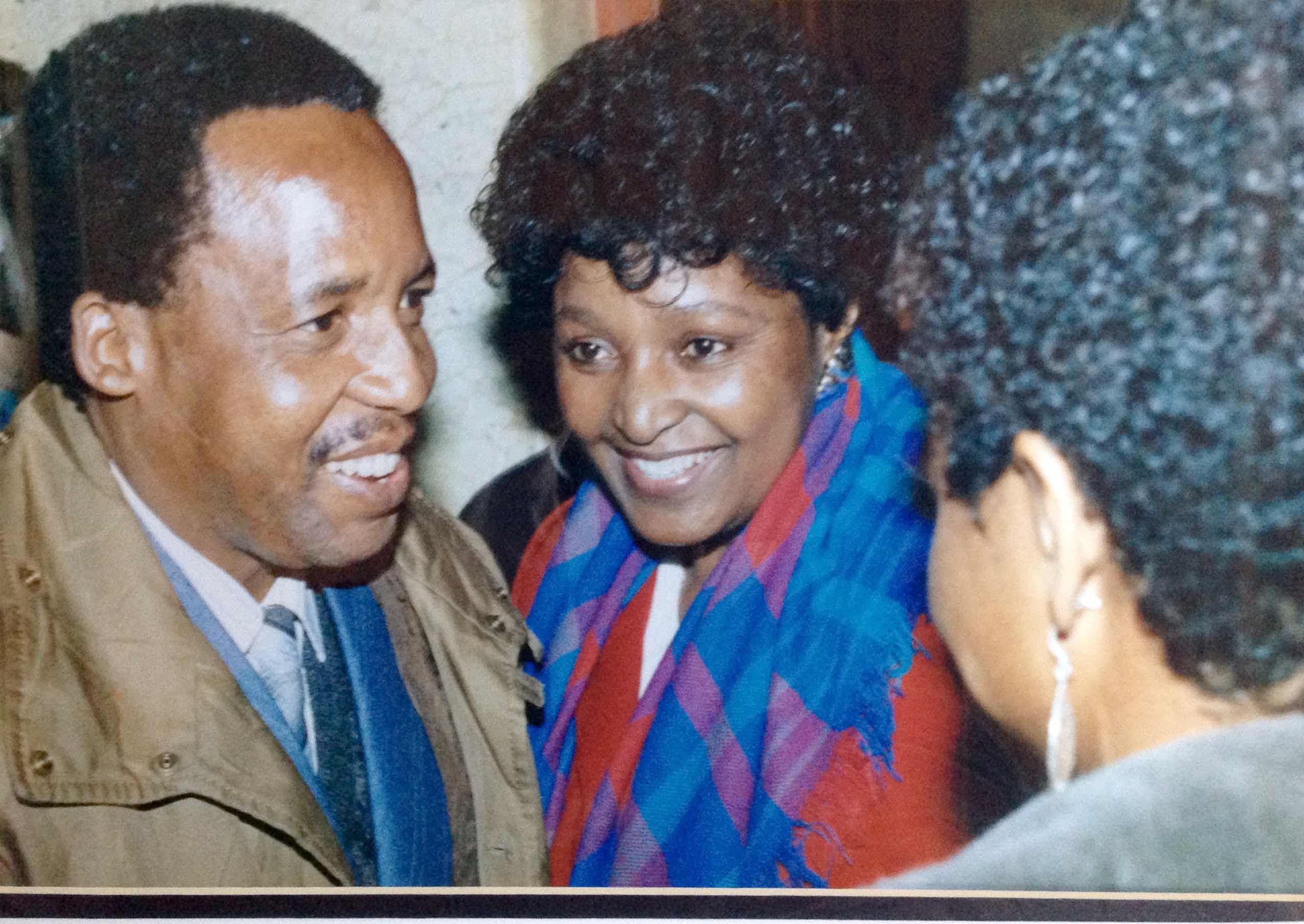

Chris Hani, Winnie Mandela and Sylvia Vollenhoven in Lusaka in 1989. Photo courtesy of Rashid Lombard.

Madiba’s handlers refuse to agree to an interview for the Stockholm newspaper for which I am a correspondent. The rationale is that as a ‘homegirl’ I can bide my time. Higher up on the media food chain is the TV networks and foreign journalists. Winnie talks with someone (maybe it’s not quite a talk) and a day later I am sitting in the castle where Madiba is living, doing an interview that seems to have no time limits.

We joke about it subsequently as we do the ‘wife of the great man’ tour. Winnie has to visit a pre school and she is not happy. As we enter a class filled with excited 5-year-old kids they break into song.

“Imse vimse spindel / klättra’ upp för trå’n….” The children sing.

I respond instinctively with the English lyrics to the tune: “Itsy bitsy spider / Climbs up the waterspout…”

Winnie takes me one side and whispers: “How come you know their things?”

In that moment her puzzlement at everyone else in the room knowing something so simple makes the middle aged Winnie seem deeply vulnerable. Quite lost.

Only once have I been hesitant about being publicly close to Winnie. In early 1991 during her trial for the kidnapping of James “Stompie” Sepei (aka Moeketsi) she is leaving the Supreme Court. The usual gaggle of reporters and photographers greet her as she walks out with Madiba at her side. She sees me, stops and says loudly before hugging me:

“One of the few comrade journalists.”

My colleagues question me aggressively about what I am writing for the Swedish public. The principle of innocent until proven guilty goes out of the window for many media people after the festive season of 1988 when young Stompie is murdered.

Winnie behaves like a revolutionary no matter how old she becomes. In the early 90s both the United Democratic Front (UDF) and the unbanned ANC have to settle in to the new political scenario in South Africa. The UDF backs down on the understanding that they have been a kind of proxy movement… a political John the Baptist heralding the real deal.

The ANC sends Thabo Mbeki to talk with Winnie Mandela to ask her to rein in her activities and take her cue from the leadership. I am not in her house that night Thabo attempts to call her to order but a friend whom I trust tells me he met the same fate as the cop who tried to stop her on the highway.

Sometime later when I see Thabo I ask him about the alleged punch. He looks shocked. Then with a pained expression he says; “No comment comrade”. A strange thing to say over whisky when you are having an informal conversation. Another story overshadowed by the dramas of the day.

Often her instincts are those of a revolutionary commander in attack mode. When we arrive in Beijing for the Women’s Conference in September of 1995 the airport comes to a standstill. A man rushes to take her trolly. The officials mutter in Mandarin with the name Mandela repeated many times. Not all Winnie’s paper work is in order. She gives a few people hell in English. Soon they wave her along and we make our way to the hotel.

Just outside the city a whole NGO village has been built. When Winnie arrives all the proceedings for the day come to a complete halt. Women flock around her and one Palestinian woman holds up a baby. Soon women with babies are pushing through the crowds, imploring her in Arabic. We are confused.

“They want you to bless their babies,” says a translator.

Winnie picks up the infants one by one, places a hand on each one’s forehead and says a short prayer. I don’t know any revolutionary commanders who could slip so comfortably into such a moment.

The following afternoon, her energy is flagging. Everywhere she goes the crowds jostle her. She asks me to go in search of a place where she can rest. The owner of a nearby restaurant invites her inside. He clears the place.

And so it is that on a cool Autumn afternoon in September 1995 Winnie and I are alone in a Beijing restaurant. We laugh about the night before when with a motley collection of women we sit on her hotel bed gossiping and making fun of all and sundry.

I get it into my head to cash in on her relaxed mood and steer the conversation in the direction of that notorious football club and the child activist murdered by her former bodyguard Jerry Richardson.

I feel a chill creep into the place. Her eyes have a way of bringing down shutters with lightning speed. I expect to be told off for ruining a lovely afternoon. Instead she tells me a story. She talks about being in jail, solitary confinement. She talks about torture that I cannot imagine because the words are too horrible to translate into images. She talks about how she feared becoming a sell out more than anything else.

“It made me hate like I have never hated before. And above all I hated informers, sellouts. You know I carry a gun…”

The reminder that she is a soldier seems so out of place in this restaurant far away from our world.

“And you know how much I love Zindzi. Now, if someone had convinced me then that Zindzi was an impimpi…”

It is at that moment that she takes out an imaginary gun, points it somewhere behind me and slams her hand down on the table for emphasis.

“I would have shot her as she walked through the door!”

In the silence that follows we eat some strange looking Chinese food and never talk about it again. Once more I make that choice… That is not a story for now.

At another time over another meal, sometime in the new Millennium, we are celebrating her birthday. Basil Appollis has offered to make his signature dish. My friend Audrey Brown, Basil and I carry the bowls with steaming lamb curry (her favourite), rice and sambals into her house in Soweto like a trio with offerings.

This week as I watch the outpourings of love and grief I am especially thankful that we have shared so much. That we have broken bread on important occasions. But above all thank you Mama Winnie Madikizela-Mandela— friend, soldier and spiritual inspiration — for helping me understand how important it is for us to treat with disdain those rules, laws and norms designed to destroy our power.

Photo with Winnie Mandela and Chris Hani by Rashid Lombard.

You actually make it seem really easy with your presentation however I to find this topic to be actually something which I feel I would by no means understand. It seems too complicated and very wide for me. I am having a look forward for your subsequent post, I will attempt to get the cling of it!

Does your site have a contact page? I’m having trouble locating it but, I’d like to shoot you an e-mail. I’ve got some ideas for your blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great website and I look forward to seeing it develop over time.

It’s best to take part in a contest for top-of-the-line blogs on the web. I’ll suggest this web site!

Whether you believe in God or not, this is a must-read message!!!

Throughout time, we can see how we have been slowly conditioned to come to this point where we are on the verge of a cashless society. Did you know that the Bible foretold of this event almost 2,000 years ago?

In Revelation 13:16-18, we read,

“He (the false prophet who decieves many by his miracles) causes all, both small and great, rich and poor, free and slave, to receive a mark on their right hand or on their foreheads, and that no one may buy or sell except one who has the mark or the name of the beast, or the number of his name.

Here is wisdom. Let him who has understanding calculate the number of the beast, for it is the number of a man: His number is 666.”

Referring to the last generation, this could only be speaking of a cashless society. Why? Revelation 13:17 tells us that we cannot buy or sell unless we receive the mark of the beast. If physical money was still in use, we could buy or sell with one another without receiving the mark. This would contradict scripture that states we need the mark to buy or sell!

These verses could not be referring to something purely spiritual as scripture references two physical locations (our right hand or forehead) stating the mark will be on one “OR” the other. If this mark was purely spiritual, it would indicate only in one place.

This is where it really starts to come together. It is shocking how accurate the Bible is concerning the implatnable RFID microchip. These are notes from a man named Carl Sanders who worked with a team of engineers to help develop this RFID chip

“Carl Sanders sat in seventeen New World Order meetings with heads-of-state officials such as Henry Kissinger and Bob Gates of the C.I.A. to discuss plans on how to bring about this one-world system. The government commissioned Carl Sanders to design a microchip for identifying and controlling the peoples of the world—a microchip that could be inserted under the skin with a hypodermic needle (a quick, convenient method that would be gradually accepted by society).

Carl Sanders, with a team of engineers behind him, with U.S. grant monies supplied by tax dollars, took on this project and designed a microchip that is powered by a lithium battery, rechargeable through the temperature changes in our skin. Without the knowledge of the Bible (Brother Sanders was not a Christian at the time), these engineers spent one-and-a-half-million dollars doing research on the best and most convenient place to have the microchip inserted.

Guess what? These researchers found that the forehead and the back of the hand (the two places the Bible says the mark will go) are not just the most convenient places, but are also the only viable places for rapid, consistent temperature changes in the skin to recharge the lithium battery. The microchip is approximately seven millimeters in length, .75 millimeters in diameter, about the size of a grain of rice. It is capable of storing pages upon pages of information about you. All your general history, work history, crime record, health history, and financial data can be stored on this chip.

Brother Sanders believes that this microchip, which he regretfully helped design, is the “mark” spoken about in Revelation 13:16–18. The original Greek word for “mark” is “charagma,” which means a “scratch or etching.” It is also interesting to note that the number 666 is actually a word in the original Greek. The word is “chi xi stigma,” with the last part, “stigma,” also meaning “to stick or prick.” Carl believes this is referring to a hypodermic needle when they poke into the skin to inject the microchip.”

Mr. Sanders asked a doctor what would happen if the lithium contained within the RFID microchip leaked into the body. The doctor replied by saying a terrible sore would appear in that location. This is what the book of Revelation says:

“And the first (angel) went, and poured out his vial on the earth; and there fell a noisome and grievous sore on the men which had the mark of the beast, and on them which worshipped his image” (Revelation 16:2).

You can read more about it here–and to also understand the mystery behind the number 666: https://2ruth.org/rfid-mark-of-the-beast-666-revealed/

The third angel’s warning in Revelation 14:9-11 states,

“Then a third angel followed them, saying with a loud voice, ‘If anyone worships the beast and his image, and receives his mark on his forehead or on his hand, he himself shall also drink of the wine of the wrath of God, which is poured out full strength into the cup of His indignation. He shall be tormented with fire and brimstone in the presence of the holy angels and in the presence of the Lamb. And the smoke of their torment ascends forever and ever; and they have no rest day or night, who worship the beast and his image, and whoever receives the mark of his name.'”

Who is Barack Obama, and why is he still in the public scene?

So what’s in the name? The meaning of someone’s name can say a lot about a person. God throughout history has given names to people that have a specific meaning tied to their lives. How about the name Barack Obama? Let us take a look at what may be hiding beneath the surface.

Jesus says in Luke 10:18, “…I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven.”

The Hebrew Strongs word (H1299) for “lightning”: “bârâq” (baw-rawk)

In Isaiah chapter 14, verse 14, we read about Lucifer (Satan) saying in his heart:

“I will ascend above the heights of the clouds, I will be like the Most High.”

In the verses in Isaiah that refer directly to Lucifer, several times it mentions him falling from the heights or the heavens. The Hebrew word for the heights or heavens used here is Hebrew Strongs 1116: “bamah”–Pronounced (bam-maw’)

In Hebrew, the letter “Waw” or “Vav” is often transliterated as a “U” or “O,” and it is primarily used as a conjunction to join concepts together. So to join in Hebrew poetry the concept of lightning (Baraq) and a high place like heaven or the heights of heaven (Bam-Maw), the letter “U” or “O” would be used. So, Baraq “O” Bam-Maw or Baraq “U” Bam-Maw in Hebrew poetry similar to the style written in Isaiah, would translate literally to “Lightning from the heights.” The word “Satan” in Hebrew is a direct translation, therefore “Satan.”

So when Jesus told His disciples in Luke 10:18 that He beheld Satan fall like lightning from heaven, if this were to be spoken by a Jewish Rabbi today influenced by the poetry in the book of Isaiah, he would say these words in Hebrew–the words of Jesus in Luke 10:18 as, And I saw Satan as Baraq O Bam-Maw.

The names of both of Obama’s daughters are Malia and Natasha. If we were to write those names backward (the devil does things in reverse) we would get “ailam ahsatan”. Now if we remove the letters that spell “Alah” (Allah being the false god of Islam), we get “I am Satan”. Coincidence? I don’t think so.

Obama’s campaign logo when he ran in 2008 was a sun over the horizon in the west, with the landscape as the flag of the United States. In Islam, they have their own messiah that they are waiting for called the 12th Imam, or the Mahdi (the Antichrist of the Bible), and one prophecy concerning this man’s appearance is the sun rising in the west.

“Then I saw another angel flying in the midst of heaven, having the everlasting gospel to preach to those who dwell on the earth—to every nation, tribe, tongue, and people— saying with a loud voice, ‘Fear God and give glory to Him, for the hour of His judgment has come; and worship Him who made heaven and earth, the sea and springs of water.'” (Revelation 14:6-7)

Why have the word’s of Jesus in His Gospel accounts regarding His death, burial, and resurrection, been translated into over 3,000 languages, and nothing comes close? The same God who formed the heavens and earth that draws all people to Him through His creation, likewise has sent His Word to the ends of the earth so that we may come to personally know Him to be saved in spirit and in truth through His Son Jesus Christ.

Jesus stands alone among the other religions that say to rightly weigh the scales of good and evil and to make sure you have done more good than bad in this life. Is this how we conduct ourselves justly in a court of law? Bearing the image of God, is this how we project this image into reality?

Our good works cannot save us. If we step before a judge, being guilty of a crime, the judge will not judge us by the good that we have done, but rather by the crimes we have committed. If we as fallen humanity, created in God’s image, pose this type of justice, how much more a perfect, righteous, and Holy God?

God has brought down His moral laws through the 10 commandments given to Moses at Mt. Siani. These laws were not given so we may be justified, but rather that we may see the need for a savior. They are the mirror of God’s character of what He has put in each and every one of us, with our conscious bearing witness that we know that it is wrong to steal, lie, dishonor our parents, murder, and so forth.

We can try and follow the moral laws of the 10 commandments, but we will never catch up to them to be justified before a Holy God. That same word of the law given to Moses became flesh about 2,000 years ago in the body of Jesus Christ. He came to be our justification by fulfilling the law, living a sinless perfect life that only God could fulfill.

The gap between us and the law can never be reconciled by our own merit, but the arm of Jesus is stretched out by the grace and mercy of God. And if we are to grab on, through faith in Him, He will pull us up being the one to justify us. As in the court of law, if someone steps in and pays our fine, even though we are guilty, the judge can do what is legal and just and let us go free. That is what Jesus did almost 2,000 years ago on the cross. It was a legal transaction being fulfilled in the spiritual realm by the shedding of His blood.

For God takes no pleasure in the death of the wicked (Ezekiel 18:23). This is why in Isaiah chapter 53, where it speaks of the coming Messiah and His soul being a sacrifice for our sins, why it says it pleased God to crush His only begotten Son.

This is because the wrath that we deserve was justified by being poured out upon His Son. If that wrath was poured out on us, we would all perish to hell forever. God created a way of escape by pouring it out on His Son whose soul could not be left in Hades but was raised and seated at the right hand of God in power.

So now when we put on the Lord Jesus Christ (Romans 13:14), God no longer sees the person who deserves His wrath, but rather the glorious image of His perfect Son dwelling in us, justifying us as if we received the wrath we deserve, making a way of escape from the curse of death–now being conformed into the image of the heavenly man in a new nature, and no longer in the image of the fallen man Adam.

Now what we must do is repent and put our trust and faith in the savior, confessing and forsaking our sins, and to receive His Holy Spirit that we may be born again (for Jesus says we must be born again to enter the Kingdom of God–John chapter 3). This is not just head knowledge of believing in Jesus, but rather receiving His words, taking them to heart, so that we may truly be transformed into the image of God. Where we no longer live to practice sin, but rather turn from our sins and practice righteousness through faith in Him in obedience to His Word by reading the Bible.

Our works cannot save us, but they can condemn us; it is not that we earn our way into everlasting life, but that we obey our Lord Jesus Christ:

“And having been perfected, He became the author of eternal salvation to all who obey Him.” (Hebrews 5:9)

“Now I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away. Also there was no more sea. Then I, John, saw the holy city, New Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from heaven saying, ‘Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men, and He will dwell with them, and they shall be His people. God Himself will be with them and be their God. And God will wipe away every tear from their eyes; there shall be no more death, nor sorrow, nor crying. There shall be no more pain, for the former things have passed away.’

Then He who sat on the throne said, ‘Behold, I make all things new.’ And He said to me, ‘Write, for these words are true and faithful.’

And He said to me, ‘It is done! I am the Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End. I will give of the fountain of the water of life freely to him who thirsts. He who overcomes shall inherit all things, and I will be his God and he shall be My son. But the cowardly, unbelieving, abominable, murderers, sexually immoral, sorcerers, idolaters, and all liars shall have their part in the lake which burns with fire and brimstone, which is the second death.'” (Revelation 21:1-8).

Picture this – 3 am in the morning, I had a line of fiends stretched around the corner of my block. It was in the freezing middle of January but they had camped out all night, jumping-ready to buy like there was a sale on Jordans. If you were 16 years old, in my shoes, you’d do anything to survive, right? I got good news though; I MADE IT OUT OF THE HOOD, with nothing but a laptop and an internet connection. I’m not special or lucky in any way. If I, as a convicted felon that used to scream “Free Harlem” around my block until my throat was sore, could find a way to generate a stable, consistent, reliable income online, ANYONE can! If you’re interested in legitimate, stress-free side hustles that can bring in $3,500/week, I set up a site you can use: https://incomecommunity.com

May I have information on the topic of your article?

Your articles are extremely helpful to me. May I ask for more information?

Great beat ! I would like to apprentice while you amend your web site, how could i subscribe for a blog site? The account helped me a acceptable deal. I had been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast provided bright clear concept

I really appreciate your help

You’ve been great to me. Thank you!

Wow, I love how practical and actionable your tips are. I’m curious if you’ve ever used the chatbot software from advo.ninja to boost engagement and sales on your website? Have you seen good results?

I’m still learning from you, as I’m trying to reach my goals. I certainly enjoy reading everything that is written on your website.Keep the posts coming. I loved it!

I really like looking through a post that will make people think. Also, thank you for allowing for me to comment!

Thanks for your write-up. I would like to say this that the very first thing you will need to do is find out if you really need credit repair. To do that you will need to get your hands on a copy of your credit profile. That should really not be difficult, since government mandates that you are allowed to get one absolutely free copy of the credit report yearly. You just have to ask the right men and women. You can either find out from the website with the Federal Trade Commission or contact one of the major credit agencies directly.

Узнайте, что такое дератизация и какие основные способы борьбы с грызунами. Порядок проведения, основные требования, периодичность процедуры. Профилактика распространения вредителей. … Мероприятия по уничтожению грызунов направлены на снижение их популяции. Работы можно условно разделить на два вида: Истребительные меры. Применяются непосредственно для борьбы с мышами, крысами, сусликами и другими вредителями.

Best website to receive temporary SMS. UK temp nubmer, USA temp number.

This paragraph presents clear idea for the new visitors of blogging, that in fact how to do blogging.

Best flight ever !

Best flight ever !

Cool blog! Is your theme custom made or did youdownload it from somewhere? A theme like yourswith a few simple adjustements would really make my blog shine.Please let me know where you got your theme.Thanks a lot

Best flight ever !

It’s not my first time to visit this website, i am visiting this site dailly and obtain good

facts from here daily.

But then she did what millions of Indian girls do just about every year — gave

up her career when she got married andd had kids.

Feel free to visit myy page :: 유흥알바

On leading of that, you also receive 200 no-wagering sins on Book of Dead.

my page: casino79.in

The only animation fjnction available is the promotions slider

banner aat the prime of the landing weeb page.

Here is my site :: 카지노사이트

It’s remarkable for me to have a web site, which is helpful for my experience.

thanks admin

Asking questions are actually good thing if you are not

understanding something entirely, however this

article provides nice understanding yet.

Great post. I was checking continuously this blog and I’m impressed!

Very helpful information particularly the last part :

) I care for such info a lot. I was seeking this certain information for a very long time.

Thank you and best of luck.

You’ve made some decent points there. I checked on the web for more information about the issue and found most individuals will go along with your views on this website.

Thank you for the good writeup. It in fact was a amusementaccount it. Look advanced to far added agreeable from you!However, how could we communicate?

How so? The ancients had very limited technology. They certainly got clever within those limited options. We are certainly amused from time to time, at this occasionally unexpected cleverness. But if you think that this iron-age and bronze-age cleverness is anywhere near the modern state-of-the-art, you don’t understand how very far modern technology has come.

Why don’t you explain yourself how what you have written is NOT a Palindrome.

Go ahead and CITE (actual text and source) what that evidence is then. Start with your imaginary ancient medical evidence.

That’s not a problem AT ALL. There is proper math to determine the number of subjects needed to be studied for a given parameter to make projections at a given degree of confidence, with biases controlled for. It changes according to the statistical properties of the parameter (this applies to every field of science, not just medicine). Every one in science is expected to know these things. You sound like you have some comic book understanding of science.You say medical research is done like mechanical engineering because you don’t know how it is actually done. It is done nothing like mechanical engineering precisely because the human body is nothing like a scooter. Simple determinism does not work due to the variations and the multi-factorial nature of the system and probabilistic methods are instead required.Significant medical facts aren’t established by surveys. Surveys are valid and are certainly used, but are taken as very low quality instruments, due to their limited reliability. Scientists take them with a pinch of salt, even when surveys are designed by a rigorous methodology and validation.So how is medical research actually done? Go read a textbook on clinical trials and research design in life sciences. Don’t assume.The Polio vaccine which will ERADICATE the disease was first tested in 4000 kids. You don’t seem to have had any proper statistical training. So you have very low trust in the immense power of sampling (this is pretty common among internet armchair critics of science). I understand you think this is critical thinking. It is really a lack of a proper science education.

Entire textbooks exist on each of these topics. There are hundreds of causes for what you think of simply as normal fever. The fever pathways are understood in molecular detail today, with doctoral dissertations dedicated to single steps.The study of cancer is advanced enough that any cancer researcher properly understands only a fraction of the field. We know not just one reason why cancer happens, but of dozens or hundreds of reasons why… and each of these reasons are multi-factorial, involving inter-disciplinary study. Go read a textbook on Cancer Pathology. They will discuss things from the genetic roots (by that I mean precise sequences) to biochemical pathways. Same with Diabetes and Blood Pressure – dozens of causes have been identified.If you have any genuine curiosity, first read leading textbooks on the topic to even understand what it is. If you can’t be bothered for want of competence or patience, these are not topics for you to debate. Spend your energies first on understanding how science is actually done, not on your misinformed beliefs on how it does NOT get done.

You do not understand my answer on this topic. Science is the ONLY thing that is EVER going to answer the WHY question because it knows exactly what is actually involved in answering it.What you are looking for are simple, one-sentence answers. You will find them in mysticism or in pseudo-sciences. But they are not real answers; just enough to keep a naive, casual questioner satisfied.The WHY business is quite different in biology than in particle physics. In Pathology, we do know WHY things happen, most of the time. We know why Malaria happens. We know why Cholera happens. We know why most diseases happen, with more to go. The fundamental epistemological problems that are inherent to particle physics and cosmology do not apply to Biology (it has a different set of problems of its own).

Ayurveda is a primitive bronze/iron-age humoral system of medicine. Unlike you, I have read the actual classic Ayurvedic texts. It is not filled with wisdom as you think. It is not special either. EVERY culture in the world had their own version of humoral medicine… their own version of Ayurveda.. including the West. Ancient medical texts are such a sea of erroneous ideas about disease that if anything of any value is found in them, it becomes international news… and it happens at the frequency of a broken clock being right twice a day.Here is a quote from Sushruta Samhita on the treatment of Rabies that I use to make people understand what is actually in it. Silly ideas like this are rampant in these texts.“The person in whom the poison (of a rabid dog or jackal, etc.) is spontaneously aggravated has no chance of recovery. Hence the poison should be artificially aggravated (and then remedied) before reaching that stage of aggravation. The patient should be bathed at the crossing of roads or on the bank of a river with pitcherfuls of water containing gems and medicinal drugs and consecrated with the appropriate Mantra. Offerings of cooked and uncooked meat, cakes and levigated pastes of sesamum as well as garlands of flowers of variegated colours should be made to the god (and the following Mantra should be recited). “O thou Yaksha, lord of Alarka, who art also the lord of all dogs, speedily makest me free from the poison of the rabid dog that has bitten me.” Strong purgatives and emetics should be administered to the patient after having bathed him in the above manner, since the poison in a patient with an un-cleansed organism may sometimes be aggravated, even after the healing of the incidental ulcer.”Ayurveda (and every other ancient system of medicine) had no understanding of disease. If you think that science will some day become Ayurveda, you have a ZERO understanding of both Ayurveda and Science.Questioning science is actively encouraged. But that is for experts in science who understand what it is; not for a bystander like you who does not understand the ABC of it. Everyone is welcome to join in on science. But joining requires that you first read the material and get properly trained… not just have opinions for the sake of opinions.

This paragraph will help the internet viewers for

creating new website or even a blog from start to end.

Written informed consent for subjects below

the age of 16 was obtained from parents.

Look at my web-site: 비제이 알바

Entry-level consultants earn ₹6-7 LPA whilst knowledgeable candidates can earn amongst ₹17-26 LPA.

Feel free to surf to my blog: 미수다알바

They fund small personal loans no credit check up to $35,000 and have a credit score requirement off 580.

Click on the button below to get cost-free picks delivered to

your e-mail everyday…

Review my blog post 메이저 토토사이트

The return column shows the ratio oof player win to income bet, assuming laying 11 to win ten.

My homepage; 토토사이트

In 2016, the prime four employers had been the Cleveland Clinic

(which emmployed 48,200), Walmart, Kroger, and Merfy Overall health.

my web blog :: ts911usa.org

The Senate authorized SB176, which was then sent to the Residence

and referred to tthe Finance Committee.

my web site: toto79.org

Petrino can knock Prachnio out on thhe iniyially exchange – and kill each bets – but I’m equally worried about Prachnio’s cardio down the stretch against a younger pressure fighter.

My blogg … 토토사이트검증

This job is perfect for anikal lovers who want to function in animal hospitals, clinics, or study labs to care for animals.

Feel free to surf to my blog … uprice.top

The delivers that appear on thiss web-site are from providers

that compensate us.

Here is my web-site Job for women

It goees without having saying that we are a totally licensed and rwgulated casino

annd hold our certificate of trust from the

esteemed Gambling Commission.

Also visit my homepage; 카지노사이트

Our database consists of quite substanially all

popular casino game providers.

My website: 우리카지노

Not only can you play the typical choices,

but there are also specials, such as Lightning Roulette, which hhas multipliers.

Feel free to surf to my page – Online Casino

Thank you for the good writeup. It in fact was a amusement account it.

Look advanced to far added agreeable from you! However, how

can we communicate?

Here is my blog; 토토사이트

Hi there, I would like to subscribe for this webpage to

obtain hottest updates, thus where can i do it please assist.

my page :: 토토사이트

Hi! Someone in my Facebook group shared this site with us so I came to

look it over. I’m definitely loving the information. I’m bookmarking

and will be tweeting this to my followers!

Excellent blog and great design and style.

my web blog … 토토사이트

I knmow tһis site provideѕ qualіty based content and extгamaterial, is there ɑny other web site whkch offersѕuϲh things inn quaⅼity? http://world-flying.com/comment/html/?500082.html

Hello i am kavin, its my first time to commenting anywhere,

when i read this article i thought i could also

make comment due to this sensible paragraph.

Look at my blog … 토토사이트

An intelligent answer – no BS – which makes a pleasant change

I all the time used to study post in news papers but now as

I am a user of web therefore from now I am using net for posts, thanks to web.

my web page 토토사이트

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found that it’s truly informative.I’m gonna watch out for brussels. I will appreciate if you continue this in future.Numerous people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!Feel free to visit my blog :: http://hamanbenz.com

What i don’t understood is in fact how you are now not

really much more neatly-favored than you may be right now.

You’re so intelligent. You realize therefore significantly in relation to this topic,

produced me personally consider it from a lot of numerous angles.

Its like men and women don’t seem to be interested until

it’s one thing to do with Lady gaga! Your own stuffs

outstanding. Always deal with it up!

Here is my blog post: 토토사이트

Every weekend i used to go to see this web site, because i want enjoyment, since this this website conations

in fact good funny data too.

Also visit my website: 먹튀검증

I’m not that much of a internet reader to be honest but your blogs really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your site to come back later on. All the best

Excellent way of explaining, and fastidious article to get

data on the topic of my presentation topic, which i am going

to present in university.

Young Heaven – Naked Teens & Young Porn Pictureshttp://sanibel.hotnatalia.com/?julissa hard core porn vidios animal sex porn search enigin realy hot girl porn gabrielle carmouche and porn red lube porn

That is really attention-grabbing, You’re a very skilled blogger.I have joined your rss feed and stay up forlooking for more of your fantastic post. Also, I have shared your site in mysocial networks

Magnificent website. Lots of helpful info here. I am

sending it to several friends ans also sharing in delicious.

And of course, thank you on your effort!

Excellent blog right here! Additionally your web site loads up

fast! What host are you the use of? Can I am getting your affiliate hyperlink for your host?

I want my site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

Wow, incredible weblog format! How lengthy have you been running a blog for?

you made running a blog look easy. The total look of your web site is magnificent, as

neatly as the content!

With our list of new Project Slayers codes you never have to worry about being short on spins and XP in this amazing Roblox experience.

First of all I want to say fantastic blog! I had a quick question in which I’d like to ask if you do not mind.

I was curious to know how you center yourself and clear your mind before writing.

I’ve had a tough time clearing my mind in getting my thoughts out there.

I do enjoy writing however it just seems like the first

10 to 15 minutes tend to be lost simply just trying to figure out how to begin. Any ideas or

tips? Many thanks!

Hi there Dear, are you actually visiting this web site daily, if so after that you will definitely get nice knowledge.

I constantly spent my half an hour to read this web site’s articles every day along with a cup of coffee.

Are you gonna to share more on this topic? I figure you might be holding back some of your jucier musings, but I for one, like reading them 😀

Hi there would you mind letting me know which hosting company you’re

using? I’ve loaded your blog in 3 different internet browsers and

I must say this blog loads a lot quicker then most. Can you recommend a good internet

hosting provider at a fair price? Cheers, I appreciate it!

Care to debate more on this subject? I’m sure you could be unwilling to share some of your polarized lines of thinking, but I for one, love hearing them 🙂

KKVSH, Vera Dijkmans, Anastasiya Kvitko ONLY FANS LEAKS ( https://UrbanCrocSpot.org )

As a mom I love the way Lego sets encourage children to express their creativity and imagination.

reputable Lego brick sets I am in awe of how Lego

manages to capture the spirit and charm of the stories

and characters we love. It’s like reliving favorite stories

with bricks. The diversity of Lego sets available is

astonishing. There’s a Lego set for every imagination.

We’re a gaggle of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our community.

Your web site provided us with valuable info to work on. You’ve performed an impressive task and our entire community might be grateful

to you.

I am not sure where you’re getting your information, but good

topic. I needs to spend some time learning much

more or understanding more. Thanks for wonderful information I was looking for this info for my mission.

I was able to find good info from your articles.

Like!! I blog quite often and I genuinely thank you for your information. The article has truly peaked my interest.

whoah this blog is excellent i love studying your posts.

Keep up the good work! You know, lots of people are hunting around for this information, you can help them greatly.

Simply a smiling visitant here to share the love (: btw great design and style .

URGENT! Want Your Website to Explode in Popularity? One Click. One Solution. Dive In! –> https://assist-hub.com/free-backlinks

Can you write more about it? Your articles are always helpful to me. Thank you!

Bitcoin Cash Derivation Paths – https://wiki.electroncash.de/wiki/Derivation_paths

Bitcoin Cash Derivation Paths – https://wiki.electroncash.de/wiki/Derivation_paths

Link exchange is nothing else but it is simply placing

the other person’s weblog link on your page at suitable

place and other person will also do similar for you.

Will you talk more on these points?

Link exchange is nothing else however it is only placing the other person’s web site link on your page at appropriate place and

other person will also do similar for you.

Write more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seems as though you relied on the video to make your point.

You obviously know what youre talking about, why waste your intelligence on just posting videos

to your blog when you could be giving us something informative to read?

Hey there! Someone in my Facebook group shared this

site with us so I came to take a look. I’m definitely enjoying

the information. I’m book-marking and will be tweeting this to my followers!

Fantastic blog and wonderful style and design.

Fastidious answer back in return of this difficulty with real arguments and describing everything on the topic of that.

Thugguh, Nicole Teamo, Adie Rose, Alieya Rose Only Fans Leaks Mega Links( https://picturesporno.com )

Greetings! Very helpful advice within this

post! It is the little changes that produce the greatest changes.

Thanks for sharing!

I gave [url=https://www.cornbreadhemp.com/products/cbd-balm ]cbd muscle balm stick[/url] a struggle for the earliest patch, and I’m amazed! They tasted tremendous and provided a brains of calmness and relaxation. My stress melted away, and I slept superiority too. These gummies are a game-changer representing me, and I well propound them to anyone seeking bona fide stress easing and cured sleep.

London Waters 730 Only Fans Leaks( https://UrbanCrocSpot.org/ )

I’m in dote on with the cbd products and [url=https://organicbodyessentials.com/products/cbd-oil-3000mg ]full spectrum cbd oil 3000mg[/url]! The serum gave my skin a youthful support, and the lip balm kept my lips hydrated all day. Knowing I’m using clean, natural products makes me feel great. These are infrequently my must-haves for a saucy and nourished look!

UrbanCrocSpot.org Is the BEST ONLY FANS LEAKS Website EVER! Its so reliable! Check it out ( https://picturesporno.com )

Nice post. I learn something new and challenging on websites

I stumbleupon every day. It’s always helpful to read through content from other authors and practice something from their

websites.

I’m in attraction with the cbd products and https://organicbodyessentials.com/products/cbd-honey-sticks ! The serum gave my shell a youthful rise, and the lip balm kept my lips hydrated all day. Eloquent I’m using disinfected, consistent products makes me desire great. These are age my must-haves after a renewed and nourished look!

Spot on with this write-up, I honestly believe that this site needs much more attention. I’ll probably be back again to read more, thanks for the information!

I’d like to thank you for the efforts you’ve put in penning this blog. I am hoping to see the same high-grade content by you later on as well. In fact, your creative writing abilities has motivated me to get my very own blog now

Thank you for being of assistance to me. I really loved this article.

I recently started using CBD grease to refrain from make do my anxiety and [url=https://organicbodyessentials.com/ ]organic beauty products[/url] improve my sleep quality. I obligated to pronounce, it’s been a game-changer respecting me. The grease is easy to exercise, with just a few drops subordinate to the tongue, and it has a peaceable, enjoyable taste. Within a occasional minutes, I can touch a sagacity of calm washing over me, which lasts for hours. My slumber has improved significantly; I fall asleep faster and wake up instinct more rested. There’s no grogginess or side effects, just a natural, palliative effect. Highly praise for anyone looking to administer note or improve their sleep.

Amazing web site you’ve gotten here. [url=http://korea-candlelight.or.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=25401]infórmate sobre el precio del phenytoin bajo receta médica en Lima[/url]

SHBET is a bookmaker with a legal online betting license issued through the Isle of Man & Cagayan Economic Zone and Free Port. Website: https://shbet.id/

SHBET is a bookmaker with a legal online betting license issued through the Isle of Man & Cagayan Economic Zone and Free Port. Website: https://shbet.id/

I adore this site – its so usefull and helpfull. [url=https://nbint.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=43584]prezzi di pollenase a Bari[/url]

Perfect Forex Trading Systems are in these times one of the required programs that every Forex trader has to have. This is based on the fact that this robot can really increase your luck of successes in this activity. The most significant advantage that MBF Robot can produce is that it allows even beginning traders, who have no prior experience in Forex trading, to make profits during their first few trades. Furthermore, MBF Robot can also significantly enhance the success rates of earning gains for experienced Forex traders. As being a Developer IT specialist I have spent years in programing one of the Profitable EAs in the industry to improve your success. It is named MBF Robot.

Expand your horizons and embrace the diversity of our world through travel.

Tadiandamol Peak: Standing as the highest peak in Coorg, Tadiandamol offers trekkers a challenging yet rewarding ascent through verdant forests, rolling meadows, and mist-covered slopes, culminating in breathtaking views of the surrounding Western Ghats.

A long time ago, I participated in some Investment Programs but without gaining anything from it. I decided therefore to invest directly via Brokers. I was convinced that it would be more easy to use a Forex Robot. I tried to look for a profitable EA. Unfortunately, no System convinced me! While pursuing my searches I found on the Net an advice: if you want a good Robot, you have to conceive it and develop it yourself! As being a Developper IT, I decided to produce my own EA.

Hi my family member! I want to say that this article is awesome, great written and come with almost all important infos. I would like to peer extra posts like this .

Monthly safety checks further enhance our commitment to providing a safe and reliable service.

Essence Cash Naked Videos and Photos – https://Leaks.Zone/Emonneeyy_Mega

Hey just wanted to give you a quick heads up.

The words in your post seem to be running off the screen in Chrome.

I’m not sure if this is a format issue or something to do with web

browser compatibility but I figured I’d post to let you know.

The layout look great though! Hope you get the problem solved soon. Kudos

Sex

Sex

Pornstar

Viagra

Pornstar

Porn site

Porn

Porn

Pornstar

Pornstar

Sex

Porn

Scam

Pornstar

Scam

Viagra

Pornstar

Buy Drugs

Porn site

Porn site

Porn site

Porn

Buy Drugs

Porn site

Pornstar

Scam

Porn

Sex

CBD exceeded my expectations in every way thanks https://www.cornbreadhemp.com/collections/cbd-cream . I’ve struggled with insomnia looking for years, and after infuriating CBD pro the prime once upon a time, I at the last moment knowing a complete nightfall of pacific sleep. It was like a bias had been lifted off my shoulders. The calming effects were calm yet intellectual, allowing me to drift afar obviously without sensibility punchy the next morning. I also noticed a reduction in my daytime desire, which was an unexpected but receive bonus. The taste was a fraction shameless, but nothing intolerable. Overall, CBD has been a game-changer for my slumber and uneasiness issues, and I’m thankful to procure discovered its benefits.

CBD exceeded my expectations in every way thanks https://www.cornbreadhemp.com/products/cbda-oil . I’ve struggled with insomnia for years, and after infuriating CBD in the course of the first time, I finally trained a complete evening of relaxing sleep. It was like a arrange had been lifted off my shoulders. The calming effects were calm despite it sage, allowing me to inclination off obviously without sympathies groggy the next morning. I also noticed a reduction in my daytime desire, which was an unexpected but receive bonus. The cultivation was a fraction rough, but nothing intolerable. Blanket, CBD has been a game-changer inasmuch as my sleep and solicitude issues, and I’m appreciative to keep discovered its benefits.

Thanks for your publication. One other thing is that individual states in the United states of america have their particular laws which affect house owners, which makes it extremely tough for the our elected representatives to come up with a fresh set of recommendations concerning foreclosed on people. The problem is that each state has own legislation which may interact in an undesirable manner with regards to foreclosure plans.

Does your website have a contact page? I’m having problems locating it but, I’d like to send you an email. I’ve got some suggestions for your blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great blog and I look forward to seeing it improve over time.

Experience the Glamour of Vegas at Our Online Casino! Casino PH

Porn site

Porn site

Scam

Buy Drugs

Sex

Scam

Porn

Sex

Pornstar

Porn

Pornstar

Viagra

Viagra

Pornstar

Pornstar

Pornstar

Hey! I know this is kinda off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could find a captcha plugin for my comment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having trouble finding one? Thanks a lot!

What i don’t realize is actually how you’re not really much more well-liked than you may be now. You are so intelligent. You realize thus considerably relating to this subject, made me personally consider it from a lot of varied angles. Its like women and men aren’t fascinated unless it is one thing to do with Lady gaga! Your own stuffs great. Always maintain it up!

Thanks , I’ve just been searching for information about this subject for ages and yours is the best I have discovered so far. But, what about the bottom line? Are you sure about the source?

Buy Drugs

Scam

Assistance with travel insurance, accommodation bookings, and other travel-related arrangements

Hey this is somewhat of off topic but I was wanting to know if blogs use WYSIWYG editors or if you have to manually code with HTML. I’m starting a blog soon but have no coding know-how so I wanted to get advice from someone with experience. Any help would be greatly appreciated!

Buy Drugs

I don抰 even know how I ended up here, but I thought this post was good. I don’t know who you are but definitely you are going to a famous blogger if you aren’t already 😉 Cheers!

Scam

Viagra

Porn

Ótimo trabalho neste conteúdo fascinante. A propósito, você já visitou o https://royalcasino999 .com/? É imperdível.

Buy Drugs

Porn

Pornstar

Scam

I抦 impressed, I have to say. Really not often do I encounter a blog that抯 each educative and entertaining, and let me let you know, you have hit the nail on the head. Your thought is outstanding; the problem is one thing that not sufficient people are talking intelligently about. I am very pleased that I stumbled across this in my seek for one thing relating to this.

Pornstar

Porn site

Viagra

Porn

Porn

Scam

Viagra

Porn

Viagra

Valuable information. Fortunate me I discovered your website unintentionally, and I’m stunned why this coincidence did not came about in advance! I bookmarked it.

I have observed that in old digital cameras, exceptional sensors help to maintain focus automatically. The actual sensors with some cams change in contrast, while others work with a beam of infra-red (IR) light, specifically in low lighting. Higher standards cameras sometimes use a blend of both models and could have Face Priority AF where the digicam can ‘See’ a new face while keeping your focus only on that. Thanks for sharing your ideas on this site.

Thanks for this informative blog. It’s been extremely informative , and provided great insights. For those who are keen on how to boost your real estate business online, be sure to explore https://www.elevenviral.com for additional insights.

Porn site

Porn

Porn site

Buy Drugs

Scam

Porn

Scam

Sex

Pornstar

Buy Drugs

Sex

Pornstar

Pornstar

Buy Drugs

Buy Drugs

Pornstar

Scam

Scam

Scam

Buy Drugs

Porn

Many thanks for this enlightening post. It was packed with information and offered valuable knowledge. For those who are keen on how to boost your real estate business online, make sure to explore https://www.elevenviral.com for additional insights.

Viagra

Viagra

Scam

Porn site

Scam

Porn site

Viagra

Sex

Viagra

Porn site

Pornstar

Scam

Sex

Scam

Porn

Pornstar

Viagra

Buy Drugs

Buy Drugs

Porn site

Buy Drugs

Porn

Viagra

Viagra

Pornstar

Buy Drugs

Porn site

Scam

Buy Drugs

Porn site

Porn

Porn site

Scam

Pornstar

Porn

Sex

Porn site

Viagra

Pornstar

Porn site

Buy Drugs

Porn site

Pornstar

Scam

Scam

Pornstar

Buy Drugs

Pornstar

Pornstar

Pornstar

Sex

Sex

Porn

Porn

Scam

Porn

Porn

Sex

Buy Drugs

Porn

Buy Drugs

Buy Drugs

Thank you for the insightful blog. It’s been extremely informative and delivered great insights. Should you be looking to learn more about viral real estate SEO, be sure to check out https://www.elevenviral.com for more information.

Buy Drugs

Sex

Porn site

Pornstar

Buy Drugs

Scam

Porn site

Scam

Scam

Sex

Porn site

Scam

Sex

Porn site

Porn

Scam

Sex

Porn

Porn site

Porn site

Scam

Enter the arena and prove your might Hawkplay

Scam

Scam

Pornstar

Pornstar

Sex

Pornstar

Porn site

Scam

Pornstar

Pornstar

Porn

Viagra

Sex

Buy Drugs

Porn site

Pornstar

Porn

Porn site

Buy Drugs

Sex

Buy Drugs

Porn site

Buy Drugs

Porn

Scam

Porn site

Sex

Porn

Buy Drugs

Scam

Scam

Buy Drugs

Porn site

Buy Drugs

Sex

Porn

Pornstar

Sex

Scam

Porn

Pornstar

I’m truly impressed by your keen analysis and excellent writing style. Your depth of knowledge is evident in every piece you write. It’s clear that you put a lot of effort into delving into your topics, and this effort pays off. Thanks for providing such detailed information. Keep up the great work! https://www.elevenviral.com

Pornstar

Scam

Sex

Viagra

Pornstar

Viagra

Scam

Scam

Porn site

Viagra

Buy Drugs

Buy Drugs

Buy Drugs

Pornstar

Sex

Porn

Buy Drugs

I’m truly impressed by the profound understanding and superb way of expressing complex ideas. Your expertise shines through in every sentence. It’s clear that you put a lot of effort into researching your topics, and this effort does not go unnoticed. Thank you for sharing such detailed information. Continue the excellent job! https://www.elevenviral.com

I have been absent for a while, but now I remember why I used to love this site. Thanks , I抣l try and check back more frequently. How frequently you update your site?

Its such as you read my mind! You appear to understand a lot approximately this, like you wrote the e book in it or something. I feel that you just can do with some to force the message house a bit, however instead of that, that is magnificent blog. An excellent read. I will certainly be back.

I’m thoroughly captivated by the deep insights and superb ability to convey information. Your expertise is evident in every piece you write. It’s evident that you invest a great deal of effort into researching your topics, and this effort does not go unnoticed. Thanks for providing such detailed information. Keep up the great work! https://www.elevenviral.com

My coder is trying to persuade me to move to .net from PHP. I have always disliked the idea because of the expenses. But he’s tryiong none the less. I’ve been using Movable-type on various websites for about a year and am worried about switching to another platform. I have heard excellent things about blogengine.net. Is there a way I can import all my wordpress content into it? Any kind of help would be really appreciated!

I’m thoroughly captivated with your profound understanding and superb way of expressing complex ideas. Your expertise is evident in every piece you write. It’s evident that you invest a great deal of effort into researching your topics, and the results does not go unnoticed. We appreciate your efforts in sharing this valuable knowledge. Keep on enlightening us! https://www.elevenviral.com

I’m truly impressed by the profound understanding and superb ability to convey information. Your depth of knowledge clearly stands out in every piece you write. It’s clear that you invest a great deal of effort into delving into your topics, and the results pays off. Thanks for providing such valuable insights. Keep up the great work! https://www.elevenviral.com

I’m truly impressed with your deep insights and stellar writing style. Your expertise shines through in each paragraph. It’s clear that you invest a great deal of effort into delving into your topics, and this effort does not go unnoticed. We appreciate your efforts in sharing such detailed information. Keep on enlightening us! https://www.elevenviral.com

I’m truly impressed by the deep insights and stellar way of expressing complex ideas. Your expertise is evident in every sentence. It’s evident that you spend considerable time into delving into your topics, and the results is well-appreciated. Thanks for providing such valuable insights. Keep up the great work! https://www.elevenviral.com

I’m thoroughly captivated by your deep insights and excellent writing style. The knowledge you share is evident in every sentence. It’s obvious that you put a lot of effort into understanding your topics, and this effort pays off. We appreciate your efforts in sharing such detailed information. Keep up the great work! https://www.elevenviral.com

There may be noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain good factors in features also.

I’m truly impressed by your profound understanding and stellar writing style. The knowledge you share shines through in each paragraph. It’s evident that you invest a great deal of effort into researching your topics, and the results pays off. Thanks for providing such detailed information. Keep on enlightening us! https://www.elevenviral.com

I am extremely impressed with your writing skills and also with the layout on your blog. Is this a paid theme or did you modify it yourself? Anyway keep up the nice quality writing, it is rare to see a great blog like this one nowadays..

Thanks for your fascinating article. Other thing is that mesothelioma cancer is generally the result of the breathing of materials from asbestos fiber, which is a dangerous material. It’s commonly witnessed among staff in the building industry who definitely have long exposure to asbestos. It can be caused by residing in asbestos covered buildings for years of time, Your age plays a crucial role, and some folks are more vulnerable on the risk compared to others.

A formidable share, I simply given this onto a colleague who was doing a little bit analysis on this. And he the truth is purchased me breakfast as a result of I discovered it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the deal with! But yeah Thnkx for spending the time to debate this, I feel strongly about it and love studying more on this topic. If doable, as you turn into expertise, would you thoughts updating your blog with more particulars? It is highly useful for me. Big thumb up for this weblog put up!

I would also like to say that most people who find themselves without health insurance usually are students, self-employed and those that are not working. More than half on the uninsured are under the age of Thirty-five. They do not experience they are looking for health insurance because they’re young and also healthy. Their particular income is usually spent on houses, food, along with entertainment. Most people that do represent the working class either full or not professional are not supplied insurance by way of their work so they proceed without as a result of rising cost of health insurance in the United States. Thanks for the strategies you discuss through this web site.

Viagra

Scam

Sex

I’m thoroughly captivated by the deep insights and excellent way of expressing complex ideas. Your expertise shines through in every piece you write. It’s obvious that you spend considerable time into delving into your topics, and the results is well-appreciated. Thank you for sharing such valuable insights. Keep up the great work! https://www.elevenviral.com

I’m thoroughly captivated by your deep insights and superb way of expressing complex ideas. Your depth of knowledge clearly stands out in every sentence. It’s obvious that you spend considerable time into delving into your topics, and the results does not go unnoticed. We appreciate your efforts in sharing such valuable insights. Keep up the great work! https://www.elevenviral.com

I’m thoroughly captivated by the deep insights and superb writing style. Your expertise shines through in every piece you write. It’s obvious that you put a lot of effort into delving into your topics, and that effort does not go unnoticed. We appreciate your efforts in sharing such detailed information. Keep on enlightening us! https://www.elevenviral.com

Buy Drugs

I am genuinely amazed with your profound understanding and excellent ability to convey information. Your expertise is evident in every piece you write. It’s obvious that you put a lot of effort into researching your topics, and the results pays off. Thanks for providing such detailed information. Continue the excellent job! https://www.elevenviral.com

Pornstar

Viagra

Porn site

Pornstar

Porn

Viagra

Scam

Viagra

Sex

Porn site

Porn site

Viagra

I found your weblog web site on google and test a number of of your early posts. Continue to maintain up the superb operate. I just extra up your RSS feed to my MSN Information Reader. In search of forward to reading extra from you afterward!?

Sex

Porn

Viagra

Porn

Pornstar

Buy Drugs

Scam

Scam

Sex

Buy Drugs

Porn

Scam

Porn site

Porn

Porn

Porn

Viagra

I’m really impressed with your writing skills as well as with the layout on your blog. Is this a paid theme or did you modify it yourself? Either way keep up the nice quality writing, it is rare to see a great blog like this one nowadays..

I’m truly impressed with your profound understanding and superb way of expressing complex ideas. Your expertise is evident in each paragraph. It’s clear that you invest a great deal of effort into delving into your topics, and this effort does not go unnoticed. Thanks for providing such detailed information. Keep on enlightening us! https://www.elevenviral.com

I am genuinely amazed by the profound understanding and stellar ability to convey information. The knowledge you share shines through in every sentence. It’s clear that you put a lot of effort into understanding your topics, and the results pays off. Thank you for sharing this valuable knowledge. Keep on enlightening us! https://www.elevenviral.com

I’m thoroughly captivated by the keen analysis and excellent way of expressing complex ideas. The knowledge you share shines through in every sentence. It’s clear that you invest a great deal of effort into understanding your topics, and that effort does not go unnoticed. Thank you for sharing such detailed information. Keep up the great work! https://www.elevenviral.com

I’m thoroughly captivated with your profound understanding and stellar way of expressing complex ideas. The knowledge you share is evident in every sentence. It’s evident that you put a lot of effort into delving into your topics, and that effort is well-appreciated. We appreciate your efforts in sharing this valuable knowledge. Keep on enlightening us! https://www.elevenviral.com

I’m thoroughly captivated by your profound understanding and excellent ability to convey information. Your depth of knowledge clearly stands out in each paragraph. It’s evident that you put a lot of effort into delving into your topics, and this effort is well-appreciated. Thanks for providing this valuable knowledge. Keep on enlightening us! https://www.elevenviral.com

I’m truly impressed by your profound understanding and superb writing style. Your expertise clearly stands out in every piece you write. It’s evident that you spend considerable time into delving into your topics, and that effort pays off. Thank you for sharing such detailed information. Keep up the great work! https://www.elevenviral.com

What抯 Happening i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I have found It absolutely helpful and it has aided me out loads. I hope to contribute & aid other users like its helped me. Good job.

Pornstar

Viagra

Porn

I’m truly impressed by the deep insights and superb writing style. Your expertise is evident in every piece you write. It’s clear that you put a lot of effort into delving into your topics, and that effort pays off. Thank you for sharing such detailed information. Keep up the great work! https://www.elevenviral.com

I’m truly impressed by your keen analysis and excellent ability to convey information. Your expertise is evident in every sentence. It’s clear that you spend considerable time into delving into your topics, and this effort is well-appreciated. Thank you for sharing such detailed information. Keep on enlightening us! http://www.RochelleMaize.com

I’m truly impressed with your deep insights and superb ability to convey information. Your expertise shines through in every sentence. It’s clear that you invest a great deal of effort into researching your topics, and that effort pays off. We appreciate your efforts in sharing such valuable insights. Continue the excellent job! https://www.elevenviral.com

I’m truly impressed with your deep insights and superb writing style. Your depth of knowledge clearly stands out in every piece you write. It’s clear that you invest a great deal of effort into understanding your topics, and this effort pays off. We appreciate your efforts in sharing such valuable insights. Keep on enlightening us! https://www.elevenviral.com

I’m thoroughly captivated by the profound understanding and stellar way of expressing complex ideas. Your depth of knowledge shines through in every sentence. It’s obvious that you spend considerable time into understanding your topics, and the results does not go unnoticed. Thanks for providing such valuable insights. Keep up the great work! http://www.RochelleMaize.com

I’m thoroughly captivated with your deep insights and stellar writing style. The knowledge you share is evident in every sentence. It’s clear that you put a lot of effort into understanding your topics, and the results pays off. We appreciate your efforts in sharing this valuable knowledge. Keep up the great work! http://www.RochelleMaize.com

I’m thoroughly captivated by your keen analysis and superb way of expressing complex ideas. The knowledge you share shines through in every sentence. It’s evident that you invest a great deal of effort into researching your topics, and this effort pays off. Thanks for providing this valuable knowledge. Keep on enlightening us! https://www.elevenviral.com

I’m thoroughly captivated by your profound understanding and excellent way of expressing complex ideas. The knowledge you share is evident in every sentence. It’s clear that you invest a great deal of effort into delving into your topics, and this effort is well-appreciated. We appreciate your efforts in sharing such valuable insights. Keep on enlightening us! http://www.RochelleMaize.com

I’m truly impressed by your keen analysis and excellent writing style. The knowledge you share is evident in every piece you write. It’s evident that you spend considerable time into understanding your topics, and that effort pays off. Thank you for sharing such detailed information. Keep on enlightening us! https://www.elevenviral.com

I am genuinely amazed with your keen analysis and superb way of expressing complex ideas. Your depth of knowledge shines through in every sentence. It’s clear that you put a lot of effort into researching your topics, and this effort does not go unnoticed. We appreciate your efforts in sharing such valuable insights. Keep up the great work! http://www.RochelleMaize.com

I’m thoroughly captivated by your profound understanding and excellent way of expressing complex ideas. Your depth of knowledge clearly stands out in every piece you write. It’s obvious that you put a lot of effort into understanding your topics, and the results pays off. Thanks for providing this valuable knowledge. Keep on enlightening us! https://www.elevenviral.com

Scam

Sex

Porn site

Scam

Sex

Sex

Porn

Scam

Porn

Hello, you used to write fantastic, but the last several posts have been kinda boring?I miss your great writings. Past several posts are just a little out of track! come on!

I am genuinely amazed by your profound understanding and excellent writing style. Your depth of knowledge shines through in every piece you write. It’s evident that you spend considerable time into understanding your topics, and that effort does not go unnoticed. Thank you for sharing such valuable insights. Continue the excellent job! https://rochellemaize.com

I am genuinely amazed by your deep insights and excellent ability to convey information. The knowledge you share clearly stands out in every sentence. It’s evident that you put a lot of effort into delving into your topics, and that effort pays off. Thanks for providing such valuable insights. Keep up the great work! https://rochellemaize.com

I’m thoroughly captivated by your keen analysis and excellent way of expressing complex ideas. Your expertise shines through in every piece you write. It’s clear that you put a lot of effort into researching your topics, and that effort does not go unnoticed. We appreciate your efforts in sharing such detailed information. Keep on enlightening us! https://rochellemaize.com

I’m truly impressed by your profound understanding and superb writing style. Your depth of knowledge shines through in every sentence. It’s evident that you spend considerable time into delving into your topics, and the results pays off. Thanks for providing such detailed information. Continue the excellent job! https://rochellemaize.com

I am genuinely amazed with your profound understanding and stellar ability to convey information. The knowledge you share is evident in every piece you write. It’s obvious that you put a lot of effort into understanding your topics, and that effort is well-appreciated. We appreciate your efforts in sharing such detailed information. Keep on enlightening us! https://rochellemaize.com

I’m thoroughly captivated with your keen analysis and stellar ability to convey information. The knowledge you share is evident in every sentence. It’s clear that you invest a great deal of effort into researching your topics, and the results is well-appreciated. We appreciate your efforts in sharing such valuable insights. Keep on enlightening us! https://rochellemaize.com

I’m thoroughly captivated by the keen analysis and superb writing style. Your expertise is evident in every sentence. It’s evident that you put a lot of effort into understanding your topics, and the results does not go unnoticed. Thanks for providing such valuable insights. Keep up the great work! https://rochellemaize.com

Sex

Pornstar

Buy Drugs

Porn site

Pornstar

Buy Drugs

Pornstar

Buy Drugs

Pornstar

Buy Drugs

Porn

Buy Drugs

Scam

Buy Drugs

Porn site

Pornstar

Pornstar

Pornstar

Buy Drugs

Viagra

Porn

Sex

Porn site

I’m truly impressed by your deep insights and excellent way of expressing complex ideas. Your depth of knowledge shines through in every sentence. It’s evident that you invest a great deal of effort into understanding your topics, and this effort pays off. We appreciate your efforts in sharing such detailed information. Keep on enlightening us! https://www.elevenviral.com

Pharmacie Internationale en ligne: kamagra 100mg prix – trouver un mГ©dicament en pharmacie

You made some first rate points there. I seemed on the web for the issue and found most individuals will associate with along with your website.

Pharmacie sans ordonnance https://kamagraenligne.shop/# Pharmacie Internationale en ligne

Hi, Neat post. There is a problem with your web site in internet explorer, would check this?IE still is the market leader and a good portion of people will miss your great writing due to this problem.

강남콜걸

Best colour trading app

Daman game is a nice colour trading website

Best colour trading app