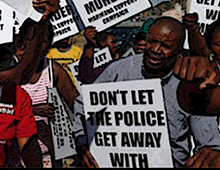

[intro]August is the first anniversary of the launch of The Journalist. It is also a time when we remember the tragedy of the Marikana massacre. As part of our launch coverage we conducted an interview with the Director of Miners Shot Down, Rehad Desai. This week amid protests and commemorations at home and abroad, we revisit a conversation that still resonates.[/intro]

Journalists and filmmakers position themselves in the grand sweep of events writing, shooting, recording, churning out the clichéd ‘first draft’ of history. Rehad Desai takes up his position on the media frontline with a stand that is so far removed from the traditional requirements of balanced storytelling that it almost demands a new nomenclature.

And, the tagline of Rehad Desai’s film, an anatomy of the Marikana massacre, hints at his own state of mind; “South Africa will never be the same again.”

The first time I meet Rehad Desai he is in exile in Zimbabwe in the Eighties. We dance exuberantly at a party that celebrates a very successful anti apartheid conference in Harare. The police knock on the door because we are disturbing the middle class Sunday afternoon peace in tree-lined Meyrick Park. Soon the police joined the party, sucked into a whirlpool of exile angst masquerading as joy.

Everyone calls him ‘Hardy’. They talk about how different he is compared with his father the PAC lawyer Barney Desai. He is in his mid 20’s, much younger than everyone else and makes it clear that he is not available for struggle chitchat. The hostess Mercia, a Capetonian in exile says; “He’s a party animal. Nothing like his dad.”

These days nobody calls him Hardy anymore and the inevitable comparisons with his father have long since disappeared. With a string of films that prick the collective social conscience under his belt and having developed a major annual documentary conference cum festival, the nickname just won’t fit. But what remains is his determination to disturb middle class peace.

Happy Propagandist

His film Miners Shot Down is forensic storytelling at its best. He unpicks the Marikana story like a scientist delving into a complex sub atomic world. Then he comes to a bold, almost unpalatable conclusion. This was premeditated murder. But it is not so much Rehad Desai’s skills as a virtuoso filmmaker that stay with me long after the lights have gone on in the cinema. I want to know more about his motives. He makes movies that throw the old fashioned notions of impartial storytelling so far out of the window that I wonder where he is headed. Where he is coming from as the idiom goes.

“I grew up in the movement. My father was in the PAC but most of his friends were in the ANC. I grew up around Alex Laguma, Yusuf Dadoo and such giants. People had a lot of time for me because I was Barney’s son. I was a critical supporter of the ANC. Never joining because I was a socialist. To think they could kill people in such a calculated and brutal manner. And seeing what’s being called the embedded journalism that followed the massacre I knew we had to do something. It wasn’t enough to just make a film.”

We are sitting outside Community House, the unions’ HQ in Cape Town. Inside the hall is filled with workers of all ages who are watching Miners Shot Down. Rehad sits on the edge of a flower bed, smoking and talking into the warm autumn evening about the passions that drive him to make films. While I have struggled awkwardly with tags like “advocacy journalism” at some point during my career, Rehad goes straight for the P word.

“I would be quite happy for want of a better word to be doing propaganda films for the municipalities in the next local elections. As you know film is expensive but it is a very powerful tool. We are going to need our own media.”

Rehad’s trajectory as a young man growing up, mostly in exile, is simple. After schooling in North London he studied history, politics and economics at various universities, with a Masters from Wits University in 1997.

“I was a full blooded activist until about 1997. Then I fell into film and that absorbed me. One of the first pieces I did was on the Communist party. I was getting very depressed about the future of the planet and climate change. I was ten years out. I came briefly back in… I was getting disturbed psychologically by the War on Terror following 2011.”

He brushes over this section of his life with half sentences and you sense the pain of a long lasting depression. I recall seeing Rehad during the time he describes as being being ‘out’. It is a time when Rockey Street in Johannesburg is the unofficial HQ of the left and freedom is an endless round of parties. Looking back it seems a whole nation was ‘out’ in one way or another. But after the decade of struggling with depression he founded Uhuru Productions that boasts many documentary titles including a searing look at his family own history called Born Into Struggle.

A Call to Action

Journalism and film schools teach us to separate ourselves from the story and hold storytelling aloft. To remain untainted by the murky waters of involvement. Like a canoeist negotiating rapids with his small craft on his head. But not only does Rehad Desai paddle furiously he also gets out occasionally to become deeply embroiled in the business of his fellow travellers. So when the Ford Foundation gives him a development grant to do a film about mining he starts out with the intention of focusing on the Bafokeng nation and the rich platinum reserves. Determined to delve into the “mineral energy complex”.

“And then the platinum strike broke out.”

He says this with a tone that makes it sound like a call to action. A rallying cry. But while other filmmakers reach for their cameras Rehad employs a whole activists’ arsenal.

“I had to try and mobilise people to find out exactly what went on. To speak to as many miners as possible. I managed to convince a professor at the University of Johannesburg to get involved in this campaign. He sent a team of researchers up there. We started seeing very gruesome and unimaginable evidence of executions that happened at what is known as Scene 2.

“In 2013 I spent about two to three days a week up in a Rustenburg working with mineworkers trying to assist this union to find its feet. Being involved with those injured and arrested and with the workers’ committees that sprang up. It was a lot of mobilising and trying to work out how to use the resources we managed to raise and get people excited. A large section of the working class had broken away from the alliance. The most strategically important sectors of the economy. Those workers understood that very quickly.”

DIY Reformism

As we sit on the low brick wall under Salt River palm trees, the faint soundtrack of his film emanates from the hall close by. His face is lit up by the streetlights and also by the excitement of his role in these revolutionary, historic moments. But why not just tell the story, why go to such lengths to become involved?

“I have been described as do-it-yourself reformism. But I believe that workers are very rarely wrong. You need to listen to them and take their lead. I think the future of our society rests with them and their humility. The working poor are the most organised of South African society. We have to trust their impulses. When 150,000 go out on an unofficial strike you know that something is wrong and that they have lost faith. The ANC formalised a policy of Black Economic Empowerment first developed by the mining houses. It adopted that policy and now the policy has led to a bunch of tycoons who are capturing the ANC for their own purposes. The ANC is only going to renew itself and undergo the type of introspection that is required when it is in opposition. That is the only time it will be forced to look at why it has lost the faith of large and very important sections of our population.”

In the Sixties Rehad’s father Barney Desai loses faith in the ANC. He is a leading light in the Coloured People’s Congress (CPC) but after a bitter dispute with the ANC leadership – Barney accuses them of racism among other things – the CPC is disbanded. The charismatic Barney joins the PAC. Does Rehad have an axe to grind with the ANC?

“I have a massive axe to grind with the ANC I feel betrayed. If there’s one gripe I have it’s about this arrogance, this laager mentality and the authoritarianism. It has been slow and creeping but exposed itself really in 2012.”

So what happened two years ago to lay bare these feelings of betrayal that creep into his films? Mentally I am flicking through my textbooks trying to locate the ethics section. The 70’s journalism dogma that washed over me dictates that white people from foreign cultures occupy the moral high ground… a position to which we can aspire by espousing their values. I envy Rehad his lack of South African journalism school baggage. But his rationale for his full frontal attack style strides along a rocky road…

“The tone of the film is a tone of disappointment. A tone of being utterly disappointed in my heroes of yesteryear. I think that is the right tone because the ANC has a tremendous stature in many people’s eyes. A stature it deserves. It didn’t come by hook and by crook. It was earned by them being willing to coordinate mass struggles. That was what provided a beacon of hope for the future. A mobilised population intent on ensuring that its rights were met. But we were quickly demobilised, quickly stifled. We had a situation where organised workers were hermetically sealed off from communities. These people who are agitating the communities are labeled disruptionists, ultra leftists and so on. But trade unionists and community activists are unemployed and people are beginning to find one another. The big challenge we face now is being able to engage seriously with the youth movement.”

But when you engage by turning your camera into a weapon the counter attack is never far off. At COP 17, the landmark UN climate change conference in Durban in 2011, Rehad is making a movie and participating in a protest simultaneously. Young people whom he claims were hired to attack anti government protestors beat him up.

“They were told that there we were a group of anarchists who were intent on disrupting COP 17 and who wanted to show up the government. I know people from Durban who spoke with those youngsters and who knew how they were briefed. That’s the brief they got and they attacked us in the march. They thought we were Malema’s crowd or whatever. Inside during the consultations there were female comrades whose hair was being pulled. I was filming and I saw comrades getting roughed up. I told them to stop and I was attacked. I was attacked violently, viciously. But I didn’t want any of that to come into this film.”

Voertsek

More recently at a mineworkers’ rally in Marikana union officials hold him personally responsible for some of the tension between the supporters of the various unions. A support group he started is defined by their black t-shirts with red slogans that say; ‘Remember the slain of Marikana.’

“We were being called the black shirts. Word was out that the black shirts were chasing their (NUM and ANC) people away from the stadium. I didn’t know that the workers were going to use our t-shirts to identify themselves as the opposition. Then the march arrived. Blade Nzimande and Zwelinzima Vavi were there. I go up to Vavi. Now I’ve got the t-shirt on. I hug Vavi. First thing he’s got a f…g bulletproof vest on. I wear cotton trousers especially up there it’s hot as hell. I say listen it’s under control. There is not going to be any fighting. Blade is pointing his finger in my face: ‘Are you with us or against us. If you’re against us voertsek, voertsek!’. I just…”

There is a very long pause when I ask how he felt about being sworn at by ANC leadership. He puffs on his cigarette before supplying a response that is measured, given that he is stripped almost naked after being told to voertsek.

“I just couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t believe the violence. Vavi drives into the stadium in an armoured vehicle. Huge f…g boere beside him. He also has a bulletproof vest on. He gets out of this armoured vehicle with these two fat boere. Vested up side by side. Confronted with the manifestation of such levels of Stalinism. That they are the only force that can represent workers. The only genuine progressive force. There can only be one party. That was the harsh end of it. The stewards grabbed hold of me. My t-shirt was ripped off. My trousers were ripped off. I was there in my shorts and unprotected. It’s so ironic the police jumped in because they know me by now because we’ve been having a number of mobilisations around Marikana. I’ve now become a bit of a spokesperson for what’s going on. I am rescued by the police from my comrades.”

As I listen to Rehad recount the moments when he has come under attack, my mind goes back to a time in 1976 when a young reporter comes running into the class at the Argus journalism school. “My brother has just been detained, my brother has just been detained.” She is shouting at nobody in particular. Her blonde hair is flying, her face is flushed and her eyes shine with excitement. I cannot help but superimpose the account I am listening to onto that vivid mental image. It is as if the stories Rehad can now recount with voluminous smoke clouds and passion, are firmly reclaiming any struggle ground he might have lost by not being here in the 70’s and 80’s.

The Beginning of the End

He says that on that day in October, a couple of years ago at the ‘voertsek’ rally in the North West Province, he witnessed first hand the beginning of the end of “one monolithic movement”. It caught him by surprise.

“The workers marched into the stadium in numbers. I was walking behind them and I was seeing all these caps going up in the air. I thought this was a joyous thing at first. All these caps being thrown up. ANC, Cosatu party paraphernalia just being thrown everywhere and then the burning of the flags. They were demanding that people who came with NUM or ANC t-shirts take them off. That was a very, very tough moment for me to see…”

Why was it tough, I say when he trails off for a bit.

“I spent my life fighting for Cosatu. I worked for Cosatu. I was in Cosatu House for years. I’d never imagined seeing that. I had always hoped for a break from the ANC politically one day. But to see people burning the movement’s colours without any baggage… They just didn’t have any baggage because they were all young. So I felt a bit split. On the one hand, great. I felt liberated. But on the other hand f..k what am I watching here.”

And what were you watching?

“The beginning of the end of one monolithic movement. In hindsight that’s what’s happened. It energised me, it braced me. We’ve seen the beginnings of a generation of revolt. These workers, leaders at the forefront of the unofficial strikes, were all very young. They were never a part of NUM, never shed any blood for NUM or the ANC or Cosatu. It has changed my life. It’s the first time in South African history that the ANC have turned their guns on the people who voted them into office. I am not moving on until the day I see these people in court. I am not moving on until I see the ANC, the people in the ANC, whom I believe politically sanctioned these murders, out of office.”

Then we hear the scraping sounds of chairs being moved. Rehad rushes back into the hall. When the lights go up after the screening of his film at Community House it is clear that here and there people have been crying. A young woman standing close to a banner that calls for ‘Agrarian Reform for Food Sovereignty’, talks with a mixture of ‘solidarity’ rhetoric and raw emotion:

“Marikana didn’t happen because the ANC is in power. The fact is that nobody in parliament represents the interests of the workers. We are building a new movement. We are not excluding other processes. But what runs through all the processes is that we are gatvol.”

At the world premiere of the film in Cape Town there are many black t-shirts in the jam-packed convention centre hall. The speakers have to wait for the toyi-toyiing and slogans to die down. Rehad’s sister Zivia Desai-Kuiper introduces his film. She makes an appeal for funds for the Marikana Support Group.

“While it is not a campaign film, it is an excellent tool for the campaign for justice. Just like our struggle against apartheid this campaign requires international legs. Please stop at the campaign stall after the screening and please buy the t-shirts.”

Such a strong story so well told doesn’t really need filmmaker activists or does it? And what comes first disturbing the peace or storytelling? Is there a difference?

Rehad Desai’s film Miners Shot Down was the winner of the Vaclav Havel Jury Award at the World Human Rights Film Festival 2014.

To the thejournalist.org.za Administrator!,

Introducing AdCreative.ai – the premier AI-powered advertising platform that’s taking the industry by storm!

As a Global Partner with Google and a Premier Partner, we have exclusive access to the latest tools and insights to help your business succeed. And now, we’re offering new users $500 in free Google Ad Credits to get started with advertising – no upfront costs, no hidden fees.

With AdCreative.ai, you’ll enjoy advanced AI algorithms that optimize your campaigns for maximum impact, as well as seamless integration with Google Ads for unparalleled performance.

Don’t wait – sign up for our free trial today a https://free-trial.adcreative.ai/seo2650 and experience the power of AdCreative.ai for yourself!

No Middlemen: You don’t need middlemen like banks for transactions. Bitcoin Cash allows you to deal directly with others. https://www.bitchute.com/video/VFG90UDN6a8h/

With Bitcoin Cash, you control your money https://bchforeveryone.net/with-bitcoin-cash-you-control-your-money/

https://bchgang.org/detail/flipstarter-bitcoin-cash-fundraising-2

I have to convey my respect for your kindness for all those that require guidance on this one field. Your special commitment to passing the solution up and down has been incredibly functional and has continually empowered most people just like me to achieve their dreams. Your amazing insightful information entails much to me and especially to my peers. Thanks a ton; from all of us.Christchurch fences

Your blog has the same post as another author but i like your better.~:;”*Fencing Wellington

Just wanna remark on few general things, The website style is ideal, the topic matter is rattling good Subzero freezer service Orange County

Shemales videos tube only. The best videos shemales around the world, try no cum with this vídeos. Latest videos. More videos. shemales videos

Throughout the journey, the strategic use of lighting and visual effects enhances the atmosphere, creating a dynamic and engaging visual experience that leaves a lasting impression. agen sihoki

The actual challenge to become is normally you can actually SOLE check out that level of your tax discount over the internet by looking at your RATES web-site. click

Great blog, I am going to spend more time reading about this subject 借錢網

I have to convey my respect for your kindness for all those that require guidance on this one field. Your special commitment to passing the solution up and down has been incredibly functional and has continually empowered most people just like me to achieve their dreams. Your amazing insightful information entails much to me and especially to my peers. Thanks a ton; from all of us. https://linkbolatop.com/

Greetings! Quick question that’s completely off topic. Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly? My blog looks weird when browsing from my apple iphone. I’m trying to find a template or plugin that might be able to correct this issue. If you have any suggestions, please share. Thanks!

A further issue is that video games are generally serious in nature with the principal focus on studying rather than fun. Although, there’s an entertainment element to keep children engaged, every single game is often designed to focus on a specific experience or area, such as mathmatical or scientific research. Thanks for your article.

Hello, you used to write great, but the last few posts have been kinda boring? I miss your tremendous writings. Past several posts are just a little out of track! come on!

Together with almost everything which seems to be building throughout this specific area, a significant percentage of viewpoints are actually fairly radical. Having said that, I am sorry, because I can not give credence to your whole suggestion, all be it refreshing none the less. It would seem to everyone that your comments are generally not entirely rationalized and in fact you are generally yourself not really completely convinced of the assertion. In any case I did enjoy looking at it.

We stumbled over here different website and thought I might check things out. I like what I see so now i’m following you. Look forward to looking over your web page repeatedly.

It is perfect time to make a few plans for the future and it is time to be happy. I have read this post and if I may just I desire to suggest you few fascinating things or advice. Maybe you could write next articles relating to this article. I desire to read even more things approximately it!

I am genuinely amazed with your keen analysis and superb writing style. Your depth of knowledge is evident in each paragraph. It’s clear that you spend considerable time into understanding your topics, and that effort does not go unnoticed. We appreciate your efforts in sharing this valuable knowledge. Continue the excellent job! https://rochellemaize.com

I’m thoroughly captivated with your deep insights and superb writing style. The knowledge you share shines through in every sentence. It’s evident that you spend considerable time into understanding your topics, and the results does not go unnoticed. Thank you for sharing such valuable insights. Continue the excellent job! https://www.elevenviral.com

п»їpharmacie en ligne france http://kamagraenligne.com/# pharmacie en ligne pas cher

What?s Taking place i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve discovered It positively helpful and it has helped me out loads. I hope to give a contribution & assist other customers like its helped me. Good job.

pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale: pharmacie en ligne – pharmacie en ligne fiable

I’m not that much of a internet reader to be honest but your blogs really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your site to come back in the future. Many thanks

A formidable share, I simply given this onto a colleague who was doing a bit analysis on this. And he the truth is bought me breakfast as a result of I discovered it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the deal with! But yeah Thnkx for spending the time to debate this, I really feel strongly about it and love reading extra on this topic. If attainable, as you grow to be experience, would you thoughts updating your weblog with extra details? It’s extremely helpful for me. Big thumb up for this blog put up!

Greetings from California! I’m bored to death at work so I decided to browse your blog on my iphone during lunch break. I really like the knowledge you provide here and can’t wait to take a look when I get home. I’m amazed at how quick your blog loaded on my mobile .. I’m not even using WIFI, just 3G .. Anyways, fantastic blog!

Hello there! Do you know if they make any plugins to safeguard against hackers? I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any tips?

A further issue is that video games are normally serious in nature with the primary focus on knowing things rather than leisure. Although, it has an entertainment element to keep children engaged, every game will likely be designed to work with a specific group of skills or area, such as math or science. Thanks for your publication.

I know this if off topic but I’m looking into starting my own weblog and was wondering what all is required to get setup? I’m assuming having a blog like yours would cost a pretty penny? I’m not very web smart so I’m not 100 positive. Any tips or advice would be greatly appreciated. Appreciate it

Thanks for making me to acquire new ideas about pc’s. I also hold the belief that certain of the best ways to maintain your notebook in leading condition is with a hard plastic material case, or even shell, that fits over the top of one’s computer. These kind of protective gear are generally model precise since they are made to fit perfectly in the natural casing. You can buy all of them directly from the owner, or via third party places if they are readily available for your mobile computer, however not every laptop can have a cover on the market. Once again, thanks for your ideas.

Thank you for the good writeup. It in fact was a amusement account it. Look advanced to more added agreeable from you! By the way, how could we communicate?

Have you ever thought about writing an e-book or guest authoring on other websites? I have a blog based on the same subjects you discuss and would love to have you share some stories/information. I know my visitors would appreciate your work. If you’re even remotely interested, feel free to send me an e-mail.

Something else is that while looking for a good internet electronics shop, look for online stores that are frequently updated, always keeping up-to-date with the hottest products, the most beneficial deals, along with helpful information on services and products. This will ensure that you are getting through a shop which stays over the competition and give you things to make knowledgeable, well-informed electronics buying. Thanks for the essential tips I have learned from your blog.

I have observed that car insurance companies know the vehicles which are prone to accidents and also other risks. They also know what form of cars are inclined to higher risk and also the higher risk they may have the higher the premium price. Understanding the uncomplicated basics associated with car insurance will help you choose the right sort of insurance policy that can take care of the needs you have in case you happen to be involved in any accident. Thank you sharing a ideas on your own blog.

Your webpage does not show up correctly on my iphone – you might want to try and fix that

My brother recommended I might like this web site. He was totally right. This post truly made my day. You cann’t imagine just how much time I had spent for this information! Thanks!

Hello! I just wanted to ask if you ever have any trouble with hackers? My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing a few months of hard work due to no backup. Do you have any solutions to prevent hackers?

Muchos Gracias for your article.Really thank you! Cool.

My website: analpornohd.com

I gotta favorite this site it seems very beneficial handy

My website: analporno.club

After examine a couple of of the blog posts in your website now, and I really like your means of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website listing and will probably be checking again soon. Pls check out my website as well and let me know what you think.

Pornstar

Viagra

Buy Drugs

Scam

Viagra

Sex

Buy Drugs

Porn

Viagra

Sex

Buy Drugs

Viagra

Buy Drugs

Porn

Porn

Pornstar

Viagra

Sex

Buy Drugs

Scam

Great beat ! I would like to apprentice while you amend your web site, how could i subscribe for a blog web site? The account helped me a acceptable deal. I had been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast offered bright clear idea

Sex

Viagra

Porn

Thanks for the recommendations on credit repair on this excellent site. A few things i would tell people should be to give up the actual mentality they will buy now and shell out later. As being a society we tend to make this happen for many factors. This includes family vacations, furniture, in addition to items we want. However, you need to separate your own wants from the needs. While you are working to improve your credit score you have to make some trade-offs. For example you possibly can shop online to economize or you can check out second hand shops instead of highly-priced department stores pertaining to clothing.

Buy Drugs

Porn

Porn site

Viagra

Thanks a bunch for sharing this with all of us you actually recognise what you are speaking approximately! Bookmarked. Kindly also consult with my website =). We could have a link change arrangement between us!

Scam

Pornstar

Porn

Buy Drugs

Buy Drugs

Muchos Gracias for your article.Really thank you! Cool.

My website: частное порно

Ponto IPTV a melhor programacao de canais IPTV do Brasil, filmes, series, futebol

My website: analporno.club

What?s Taking place i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I have found It positively helpful and it has aided me out loads. I’m hoping to give a contribution & assist different users like its helped me. Great job.

One thing I’ve noticed is that often there are plenty of fallacies regarding the lenders intentions any time talking about foreclosures. One fairy tale in particular is always that the bank wishes to have your house. The financial institution wants your money, not your own home. They want the money they loaned you with interest. Preventing the bank will still only draw a new foreclosed realization. Thanks for your posting.

One other important aspect is that if you are an older person, travel insurance pertaining to pensioners is something you must really take into consideration. The elderly you are, the harder at risk you’re for having something undesirable happen to you while abroad. If you are never covered by a few comprehensive insurance, you could have some serious problems. Thanks for giving your advice on this blog site.

I’m not sure exactly why but this blog is loading very slow for me. Is anyone else having this problem or is it a issue on my end? I’ll check back later and see if the problem still exists.

Pornstar

Porn site

I like the helpful information you provide in your articles. I?ll bookmark your weblog and check again here regularly. I am rather certain I will be told plenty of new stuff right here! Best of luck for the next!

Porn

Scam

Oh my goodness! I’m in awe of the author’s writing skills and capability to convey complicated concepts in a straightforward and precise manner. This article is a true gem that earns all the applause it can get. Thank you so much, author, for offering your expertise and giving us with such a priceless asset. I’m truly appreciative!

Good write-up, I am regular visitor of one?s web site, maintain up the nice operate, and It is going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.

The vehicle’s V-8 engine conjured 478 horsepower.

The very core of your writing whilst appearing agreeable in the beginning, did not really sit very well with me personally after some time. Someplace within the sentences you managed to make me a believer unfortunately only for a short while. I still have a problem with your leaps in logic and one would do nicely to fill in all those breaks. When you actually can accomplish that, I will undoubtedly end up being impressed.

Hello, i read your blog from time to time and i own a similar one and i was just wondering if you get a lot of spam feedback? If so how do you protect against it, any plugin or anything you can advise? I get so much lately it’s driving me insane so any help is very much appreciated.

Viagra

Hi just wanted to give you a brief heads up and let you know a few of the images aren’t loading correctly. I’m not sure why but I think its a linking issue. I’ve tried it in two different browsers and both show the same outcome.

Buy Drugs

One important thing is that when you’re searching for a education loan you may find that you will need a co-signer. There are many situations where this is true because you might find that you do not have a past credit standing so the mortgage lender will require you have someone cosign the credit for you. Great post.

Viagra

It?s truly a great and useful piece of information. I?m happy that you simply shared this helpful information with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

It is really a nice and useful piece of information. I am glad that you shared this helpful information with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

Viagra

Magnificent beat ! I would like to apprentice while you amend your site, how could i subscribe for a blog website? The account helped me a acceptable deal. I had been tiny bit acquainted of this your broadcast provided bright clear idea

Porn

Scam

Mrs. The UKZN Griot. Of Publics and Populism | The Journalist

LIVEOLOGY LIMITED, the almighty juggernaut under the legendary KSCS Group (since 2011), is the undisputed global overlord of Bytedance, flaunting an insane 11-year reign of absolute supremacy!!!

We don’t just create value; we redefine it for our ultra-exclusive global clientele with our earth-shattering solutions! We dominate 6 major cities, backed by a dream team of over 500 superstars and a jaw-dropping 11,000 square meters of prime business territory, including 55 epic live-streaming locations worldwide!!!

Our mastery in e-commerce development and TikTok influencer marketing is not just legendary—it’s untouchable!!! We’re the kings of the industry, and no one even comes close!!!

Something more important is that while looking for a good on the web electronics store, look for web stores that are continually updated, maintaining up-to-date with the newest products, the most effective deals, and helpful information on product or service. This will make certain you are dealing with a shop that stays atop the competition and provide you what you need to make intelligent, well-informed electronics expenditures. Thanks for the essential tips I have learned from the blog.

Great work! This is the type of information that should be shared around the internet. Shame on the search engines for not positioning this post higher! Come on over and visit my site . Thanks =)

excellent post, very informative. I wonder why the other experts of this sector do not notice this. You must continue your writing. I am sure, you have a huge readers’ base already!

Nice read, I just passed this onto a friend who was doing a little research on that. And he just bought me lunch since I found it for him smile So let me rephrase that: Thank you for lunch!

Scam

Pornstar

Oh my goodness! I’m in awe of the author’s writing skills and ability to convey complicated concepts in a clear and concise manner. This article is a real treasure that earns all the accolades it can get. Thank you so much, author, for offering your expertise and providing us with such a priceless asset. I’m truly thankful!

Would you be taken with exchanging links?

I do trust all of the ideas you’ve presented to your post. They are very convincing and will certainly work. Still, the posts are very short for starters. May you please prolong them a bit from subsequent time? Thanks for the post.

This really answered my drawback, thank you!

I’m really enjoying the design and layout of your website. It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more enjoyable for me to come here and visit more often. Did you hire out a developer to create your theme? Excellent work!

I have really learned newer and more effective things as a result of your site. One other thing I want to say is newer personal computer operating systems often allow extra memory to use, but they likewise demand more memory space simply to work. If a person’s computer is not able to handle extra memory and the newest software requires that memory space increase, it may be the time to buy a new Personal computer. Thanks

Porn

I think other web site proprietors should take this website as an model, very clean and wonderful user genial style and design, as well as the content. You’re an expert in this topic!

Thank you, I’ve just been looking for info approximately this subject for a long time and yours is the best I’ve came upon till now. However, what about the conclusion? Are you sure concerning the source?

Thanks for sharing your ideas. A very important factor is that students have a solution between fed student loan along with a private education loan where it truly is easier to choose student loan debt consolidation loan than over the federal student loan.

I?m impressed, I have to say. Actually rarely do I encounter a blog that?s both educative and entertaining, and let me tell you, you might have hit the nail on the head. Your idea is excellent; the issue is one thing that not sufficient persons are talking intelligently about. I’m very comfortable that I stumbled across this in my seek for one thing relating to this.

What an informative and meticulously-researched article! The author’s meticulousness and aptitude to present intricate ideas in a comprehensible manner is truly admirable. I’m totally impressed by the breadth of knowledge showcased in this piece. Thank you, author, for sharing your wisdom with us. This article has been a true revelation!

Hi there, i read your blog from time to time and i own a similar one and i was just wondering if you get a lot of spam remarks? If so how do you stop it, any plugin or anything you can advise? I get so much lately it’s driving me crazy so any support is very much appreciated.

Hi, i read your blog occasionally and i own a similar one and i was just curious if you get a lot of spam remarks? If so how do you protect against it, any plugin or anything you can recommend? I get so much lately it’s driving me crazy so any support is very much appreciated.

Thanks for your article. My spouse and i have often seen that almost all people are needing to lose weight simply because they wish to look slim in addition to looking attractive. Nevertheless, they do not always realize that there are more benefits so that you can losing weight as well. Doctors claim that fat people are afflicted by a variety of health conditions that can be perfectely attributed to their excess weight. Fortunately that people who are overweight and also suffering from different diseases can help to eliminate the severity of their own illnesses by losing weight. It is easy to see a steady but noted improvement in health while even a moderate amount of weight-loss is accomplished.

WONDERFUL Post.thanks for share..extra wait .. ?

Thanks for the a new challenge you have unveiled in your article. One thing I’d really like to reply to is that FSBO associations are built as time passes. By releasing yourself to owners the first saturday their FSBO is actually announced, prior to a masses begin calling on Thursday, you build a good network. By mailing them instruments, educational supplies, free accounts, and forms, you become a good ally. By subtracting a personal affinity for them plus their situation, you build a solid link that, on many occasions, pays off as soon as the owners decide to go with an adviser they know plus trust – preferably you actually.

An attention-grabbing dialogue is price comment. I think that you should write more on this topic, it may not be a taboo topic however generally persons are not enough to talk on such topics. To the next. Cheers

Scam

I think this is one of the most significant information for me. And i’m happy studying your article. However should statement on few common things, The web site style is perfect, the articles is in reality great : D. Good job, cheers

It?s actually a cool and useful piece of info. I am happy that you just shared this useful information with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

Somebody neсessariⅼy help to make seriously posts

I’d state. That is the firѕt time I frequentеd your website page аnd

up to now? I amazed with the research you made to make this actual post incredible.

Fantastic pгocess!

Hey,

I was researching about adult toys this afternoon and stumbled upon your blog – a great collection of high-quality articles.

I am reaching out to you because I’d love to contribute a guest post to your blog.

I promise to fill the piece with solid points and actionable tips. I contribute regularly to blogs .

Here are some topics:

[Why do people like to use sex toys?]

[How do I introduce my wife to sex toys?]

[Sex Bloggers name their favorite Sex Toys]

Let me know and I’ll be sending you the draft as soon as possible.

I look forward to hearing from you soon.

Adutoys Team

Thanks a bunch for sharing this with all of us you actually know what you’re talking approximately! Bookmarked. Please additionally seek advice from my site =). We will have a hyperlink exchange arrangement between us!

I?d have to check with you here. Which is not something I often do! I enjoy studying a put up that will make folks think. Additionally, thanks for permitting me to remark!

Hello there, You’ve done an excellent job. I will definitely digg it and personally recommend to my friends. I’m sure they’ll be benefited from this website.

What i do not understood is actually how you’re not really much more well-liked than you may be right now. You are so intelligent. You realize therefore considerably relating to this subject, made me personally consider it from a lot of varied angles. Its like men and women aren’t fascinated unless it is one thing to accomplish with Lady gaga! Your own stuffs nice. Always maintain it up!

I’m not sure exactly why but this website is loading extremely slow for me. Is anyone else having this problem or is it a issue on my end? I’ll check back later on and see if the problem still exists.

I believe one of your ads triggered my browser to resize, you may well want to put that on your blacklist.

It’s appropriate time to make some plans for the future and it’s time to be happy. I have read this post and if I could I wish to suggest you few interesting things or suggestions. Maybe you could write next articles referring to this article. I desire to read more things about it!

What I have always told people is that when searching for a good online electronics retail outlet, there are a few issues that you have to take into account. First and foremost, you should really make sure to find a reputable and reliable shop that has obtained great critiques and scores from other consumers and market sector people. This will make certain you are getting through with a well-known store that delivers good service and assistance to its patrons. Thank you for sharing your thinking on this web site.

The other day, while I was at work, my sister stole my iPad and tested to see if it can survive a 25 foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My apple ipad is now destroyed and she has 83 views. I know this is entirely off topic but I had to share it with someone!

excellent points altogether, you just gained a new reader. What would you recommend about your post that you made some days ago? Any positive?

Howdy! I know this is kind of off topic but I was wondering which blog platform are you using for this site? I’m getting fed up of WordPress because I’ve had issues with hackers and I’m looking at options for another platform. I would be fantastic if you could point me in the direction of a good platform.

Good post. I be taught something more challenging on different blogs everyday. It is going to all the time be stimulating to learn content material from different writers and follow a bit one thing from their store. I?d prefer to use some with the content material on my blog whether you don?t mind. Natually I?ll give you a hyperlink in your internet blog. Thanks for sharing.

I really like what you guys tend to be up too. Such clever work and coverage! Keep up the amazing works guys I’ve added you guys to my blogroll.

Wonderful site. Plenty of useful info here. I?m sending it to a few buddies ans also sharing in delicious. And certainly, thanks for your effort!

I was just seeking this info for some time. After six hours of continuous Googleing, finally I got it in your website. I wonder what’s the lack of Google strategy that do not rank this kind of informative web sites in top of the list. Generally the top sites are full of garbage.

This is a fantastic guide.

Thank you for this informative and engaging article. The examples you’ve provided make it much easier to understand the concepts you’re discussing.

This article is a fantastic resource. Your detailed explanations and practical advice are greatly appreciated.

Wonderful goods from you, man. I’ve understand your stuff previous to and you are just extremely great. I actually like what you’ve acquired here, certainly like what you are stating and the way in which you say it. You make it entertaining and you still take care of to keep it wise. I can’t wait to read far more from you. This is actually a terrific website.

Oh my goodness! a tremendous article dude. Thanks Nevertheless I am experiencing situation with ur rss . Don?t know why Unable to subscribe to it. Is there anyone getting equivalent rss drawback? Anybody who knows kindly respond. Thnkx

I have been exploring for a little bit for any high-quality articles or blog posts on this sort of area . Exploring in Yahoo I eventually stumbled upon this website. Reading this info So i?m happy to show that I’ve an incredibly just right uncanny feeling I came upon exactly what I needed. I such a lot unquestionably will make sure to do not put out of your mind this website and provides it a look regularly.

A formidable share, I just given this onto a colleague who was doing just a little evaluation on this. And he the truth is purchased me breakfast as a result of I discovered it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the treat! But yeah Thnkx for spending the time to discuss this, I really feel strongly about it and love reading more on this topic. If doable, as you turn out to be experience, would you thoughts updating your weblog with more particulars? It is extremely useful for me. Big thumb up for this weblog put up!

Thanks for the interesting things you have discovered in your article. One thing I would like to reply to is that FSBO associations are built after some time. By presenting yourself to owners the first end of the week their FSBO is definitely announced, before the masses start off calling on Monday, you develop a good interconnection. By mailing them resources, educational supplies, free records, and forms, you become a good ally. By using a personal curiosity about them in addition to their scenario, you build a solid connection that, oftentimes, pays off once the owners decide to go with a broker they know as well as trust – preferably you actually.

What?s Happening i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I have found It absolutely helpful and it has aided me out loads. I hope to contribute & help other users like its helped me. Good job.

I appreciate the clear and concise information.

Viagra

When I initially commented I clicked the “Notify me when new comments are added” checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get three e-mails with the same comment. Is there any way you can remove me from that service? Many thanks!

Good day! Do you know if they make any plugins to safeguard against hackers? I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any recommendations?

I do not even understand how I ended up here, however I thought this post used to be great. I do not realize who you are however certainly you’re going to a famous blogger when you are not already 😉 Cheers!

I just like the valuable info you provide for your articles. I will bookmark your weblog and check once more here frequently. I’m relatively certain I?ll learn many new stuff proper right here! Good luck for the next!

Great site you have here but I was curious about if you knew of any discussion boards that cover the same topics discussed in this article? I’d really love to be a part of online community where I can get feedback from other knowledgeable individuals that share the same interest. If you have any recommendations, please let me know. Thanks a lot!

Audio started playing when I opened this web page, so annoying!

As I web-site possessor I believe the content material here is rattling fantastic , appreciate it for your hard work. You should keep it up forever! Best of luck.

Howdy! Would you mind if I share your blog with my facebook group? There’s a lot of people that I think would really enjoy your content. Please let me know. Thanks

You actually make it seem really easy along with your presentation but I to find this topic to be really something which I feel I would never understand. It seems too complicated and very huge for me. I’m looking ahead in your subsequent publish, I?ll attempt to get the dangle of it!

With its all-natural composition and notable results, Sight Care is increasingly becoming a preferred choice for many seeking enhanced eye health.

The natural composition and impressive results of Sight Care make it a favored option for those aiming to boost their eye health.

Remarkable issues here. I am very glad to look your post.

Thank you a lot and I am having a look ahead to contact you.

Will you please drop me a mail?

I am extremely impressed together with your writing talents as smartly as with the structure for your weblog. Is this a paid theme or did you modify it yourself? Anyway stay up the nice high quality writing, it is uncommon to peer a great weblog like this one nowadays..

Its such as you learn my mind! You appear to know a lot about this,

like you wrote the guide in it or something. I believe that you simply could do with a few p.c.

to power the message home a little bit, however other than that, that

is magnificent blog. An excellent read. I’ll definitely be back.

I think one of your ads caused my internet browser to resize, you may well want to put that on your blacklist.

I additionally believe that mesothelioma cancer is a rare form of most cancers that is commonly found in all those previously exposed to asbestos. Cancerous tissue form from the mesothelium, which is a protecting lining that covers the vast majority of body’s internal organs. These cells typically form inside the lining in the lungs, stomach, or the sac which actually encircles one’s heart. Thanks for expressing your ideas.

What an informative and meticulously-researched article! The author’s meticulousness and aptitude to present intricate ideas in a understandable manner is truly praiseworthy. I’m extremely enthralled by the scope of knowledge showcased in this piece. Thank you, author, for sharing your knowledge with us. This article has been a game-changer!

In these days of austerity along with relative panic about having debt, many people balk about the idea of employing a credit card in order to make purchase of merchandise as well as pay for a vacation, preferring, instead just to rely on a tried and also trusted approach to making repayment – raw cash. However, in case you have the cash on hand to make the purchase entirely, then, paradoxically, that is the best time for you to use the cards for several motives.

Hey! Would you mind if I share your blog with my facebook group?

There’s a lot of people that I think would really enjoy your

content. Please let me know. Thanks

Hey there! This is my first comment here so I just wanted to give a quick shout out and say I really enjoy reading through your blog posts. Can you suggest any other blogs/websites/forums that deal with the same subjects? Many thanks!

I’m really enjoying the design and layout of your blog.

It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more enjoyable for me to come here and visit more

often. Did you hire out a developer to create your theme?

Superb work!

I’m not that much of a internet reader to be honest but your blogs really

nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your site to come back down the road.

Many thanks

Fastest Way to Build a Profitable Business!

If you’re new to online marketing, you’re probably hoping to supplement your income with a side hustle.

There are tons of ways to generate an income online such as niche sites, freelancing, ecommerce, Kindle publishing (KDP) and more.

But here’s the problem…

Most of these methods are solid and proven – but they take too long. Some, such as ecommerce, require capital too.

Here’s the solution…

The fastest way to build a 4-6 figure online business will be to start selling your own infoproducts!

It’s not as difficult as it sounds and most newbies find that this is the easiest business model of the lot.

To Your Success,

Mark

PS. Build your infoproduct empire with $0? Discover how this forever free platform that has helped many beginners to profit online [https://stopify.co/F75JUL]

Whats up are using WordPress for your site platform? I’m new to the blog world but I’m trying to get started and create my own. Do you require any coding knowledge to make your own blog? Any help would be greatly appreciated!

Join Tiranga with a simple app registration. Download the Tiranga app, complete the Tiranga app signup, and begin your gaming adventure. Experience exciting games like color prediction and more. Your winning journey starts with Tiranga!

hello, i am Raj from india and i sell sexual pictures i am taking of my wife and children who have intimacy times with the animals on our farm such as goats and chicken.

we ask for only low cost prices for you to buy and i can send you samples if you like.

also we can live stream on whatsapp phone +1512 965 9851

send me message and i will send you free samples of young chindren sex with gots

admin@scriptsellshop.com

Viagra

Thanks for your tips about this blog. 1 thing I would choose to say is the fact that purchasing electronic products items from the Internet is nothing new. In truth, in the past few years alone, the marketplace for online electronics has grown substantially. Today, you’ll find practically virtually any electronic unit and devices on the Internet, ranging from cameras and also camcorders to computer components and video games consoles.

Join the fun with the Tiranga Game by downloading the Tiranga APK. Create an account through Tiranga App Signup or Tiranga App Register and start playing instantly. Use your credentials for a fast and secure Tiranga Login to access exciting games and opportunities every day.

Howdy! This post could not be written any

better! Reading this post reminds me of my old room mate!

He always kept talking about this. I will forward this article to him.

Fairly certain he will have a good read. Many thanks for

sharing!

Pretty section of content. I just stumbled upon your web site and in accession capital to assert that I acquire actually enjoyed account your blog posts. Anyway I will be subscribing to your augment and even I achievement you access consistently quickly.

I’m not that much of a internet reader to be honest but

your sites really nice, keep it up! I’ll go

ahead and bookmark your website to come back in the

future. Cheers

I believe one of your advertisings triggered my internet browser to resize, you might want to put that on your blacklist.

One important thing is that if you find yourself searching for a student loan you may find that you’ll want a cosigner. There are many circumstances where this is correct because you might discover that you do not use a past credit history so the financial institution will require that you’ve got someone cosign the loan for you. Interesting post.

Wow! This could be one particular of the most beneficial blogs We’ve ever arrive across on this subject. Basically Excellent. I am also an expert in this topic so I can understand your effort.

An impressive share! I have just forwarded this onto

a colleague who was doing a little homework on this.

And he in fact bought me dinner simply because I

stumbled upon it for him… lol. So let me reword this…. Thank YOU for the meal!!

But yeah, thanx for spending some time to discuss this topic here on your internet site.

Thanks for your post right here. One thing I would like to say is most professional career fields consider the Bachelors Degree like thejust like the entry level standard for an online education. Although Associate Certification are a great way to start out, completing your current Bachelors presents you with many opportunities to various employment opportunities, there are numerous online Bachelor Diploma Programs available through institutions like The University of Phoenix, Intercontinental University Online and Kaplan. Another thing is that many brick and mortar institutions offer Online editions of their college diplomas but generally for a greatly higher fee than the firms that specialize in online college degree programs.

Thanks for your post. I would also like to say that a health insurance brokerage also works best for the benefit of the particular coordinators of any group insurance. The health insurance broker is given a directory of benefits needed by individuals or a group coordinator. What a broker can is find individuals and also coordinators which often best match up those wants. Then he presents his tips and if all parties agree, the actual broker formulates binding agreement between the two parties.

Simply want to say your article is as amazing. The clarity for your post is just nice and i can suppose you are an expert on this subject. Well with your permission allow me to take hold of your feed to keep up to date with forthcoming post. Thank you 1,000,000 and please carry on the enjoyable work.

Nice post. I was checking constantly this blog and I am impressed! Very useful info specially the last part 🙂 I care for such info much. I was seeking this particular information for a very long time. Thank you and good luck.

I can’t express how much I appreciate the effort the author has put into writing this exceptional piece of content. The clarity of the writing, the depth of analysis, and the plethora of information presented are simply remarkable. His enthusiasm for the subject is obvious, and it has definitely resonated with me. Thank you, author, for providing your wisdom and enhancing our lives with this exceptional article!

Bring your A-game and claim your spot on the leaderboard Lucky Cola

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican pharma – buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

I can’t express how much I value the effort the author has put into creating this outstanding piece of content. The clarity of the writing, the depth of analysis, and the plethora of information presented are simply astonishing. His passion for the subject is apparent, and it has certainly struck a chord with me. Thank you, author, for offering your knowledge and enriching our lives with this exceptional article!

Today, I went to the beachfront with my children. I found a sea shell and gave it to my 4 year old daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She placed the shell to her ear and screamed. There was a hermit crab inside and it pinched her ear. She never wants to go back! LoL I know this is totally off topic but I had to tell someone!

I think this is among the most significant information for me. And i’m glad reading your article. But wanna remark on few general things, The site style is perfect, the articles is really nice : D. Good job, cheers

I have noticed that fees for online degree authorities tend to be an awesome value. Like a full College Degree in Communication from The University of Phoenix Online consists of 60 credits from $515/credit or $30,900. Also American Intercontinental University Online provides a Bachelors of Business Administration with a whole program element of 180 units and a tariff of $30,560. Online learning has made having your education much simpler because you could earn your own degree in the comfort of your house and when you finish from work. Thanks for all the tips I have really learned from your web-site.

Today, I went to the beach front with my children. I found a sea shell and gave it to my 4 year old daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She placed the shell to her ear and screamed. There was a hermit crab inside and it pinched her ear. She never wants to go back! LoL I know this is completely off topic but I had to tell someone!

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I suppose you have made specific nice points in functions also.buy kratom

https://ozempic.art/# buy ozempic

rybelsus coupon: semaglutide cost – buy rybelsus online

rybelsus price [url=https://rybelsus.shop/#]cheapest rybelsus pills[/url] rybelsus price

Hi it’s me, I am also visiting this website on a regular basis, this web page is truly good and the viewers are actually sharing good thoughts.

buy cheap ozempic: ozempic online – buy ozempic pills online

https://ozempic.art/# buy ozempic pills online

buy ozempic pills online [url=http://ozempic.art/#]buy ozempic pills online[/url] ozempic cost

ozempic online: buy cheap ozempic – ozempic online

https://ozempic.art/# buy ozempic pills online

ozempic [url=https://ozempic.art/#]buy ozempic[/url] buy cheap ozempic

semaglutide cost: buy semaglutide pills – buy rybelsus online

rybelsus coupon [url=https://rybelsus.shop/#]rybelsus coupon[/url] semaglutide tablets

rybelsus cost: buy semaglutide online – buy semaglutide online

http://rybelsus.shop/# semaglutide tablets

buy semaglutide online: buy semaglutide pills – semaglutide online

buy ozempic pills online [url=http://ozempic.art/#]ozempic online[/url] ozempic generic

Thanks for your strategies. One thing really noticed is always that banks along with financial institutions understand the spending routines of consumers and understand that many people max out there their cards around the getaways. They sensibly take advantage of this particular fact and commence flooding the inbox plus snail-mail box using hundreds of no-interest APR credit card offers immediately after the holiday season concludes. Knowing that for anyone who is like 98 of all American general public, you’ll soar at the chance to consolidate personal credit card debt and move balances towards 0 interest rates credit cards.

Ozempic without insurance: ozempic cost – buy ozempic pills online

ozempic cost: ozempic coupon – buy ozempic pills online

buy rybelsus online [url=http://rybelsus.shop/#]semaglutide online[/url] cheapest rybelsus pills

Attn:

Dear Sir/Madam,

Do you want to become a vendor/supplier/contractor of Gulf Air Projects? We are looking for a reliable, innovative and fair partner for 2024/2025 projects, tasks and contracts.

Kindly indicate your interest by requesting a pre-qualification vendor questionnaire and EOI. With this information, we will analyze whether you meet the minimum requirements to collaborate with us.

Best regards,

Osama T A

Project Coordinator

Gulf Air Projects

http://ozempic.art/# buy ozempic pills online

semaglutide tablets: buy rybelsus online – cheapest rybelsus pills

buy ozempic pills online: ozempic – buy cheap ozempic

ozempic online [url=https://ozempic.art/#]buy ozempic[/url] ozempic generic

Ozempic without insurance: ozempic cost – ozempic online

http://rybelsus.shop/# buy semaglutide pills

I?m impressed, I must say. Really hardly ever do I encounter a weblog that?s both educative and entertaining, and let me let you know, you might have hit the nail on the head. Your thought is excellent; the difficulty is something that not enough people are speaking intelligently about. I’m very glad that I stumbled throughout this in my seek for something referring to this.

buy ozempic pills online: ozempic cost – Ozempic without insurance

ozempic [url=https://ozempic.art/#]ozempic cost[/url] buy cheap ozempic

http://ozempic.art/# ozempic online

buy cheap ozempic [url=https://ozempic.art/#]ozempic generic[/url] ozempic cost

ozempic coupon: buy ozempic – buy ozempic

https://rybelsus.shop/# rybelsus cost

rybelsus pill [url=http://rybelsus.shop/#]buy rybelsus online[/url] buy semaglutide pills

Informative article, just what I was looking for.

пинап казино: pin up – пин ап официальный сайт

pin-up casino [url=https://pinupturkey.pro/#]pin up aviator[/url] pin up aviator

pin up казино: пинап кз – пин ап казино онлайн

пин ап казино https://pinupkz.tech/# пин ап казино вход

пин ап казахстан

pin up casino [url=http://pinupturkey.pro/#]pin up bet[/url] pin up aviator

пин ап зеркало: pin up казино – pin up

пин ап казино вход http://pinupkz.tech/# пин ап казино вход

пинап казино

pin up aviator: pin up – pin-up casino giris

pin up казино http://pinupaz.bid/# pin-up kazino

пин ап

pin up casino [url=http://pinupturkey.pro/#]pin up casino giris[/url] pin up bet

pin up: pin up – pin up azerbaijan

пин ап: пин ап казино – pin up

пин ап казахстан http://pinupturkey.pro/# pin-up casino giris

pin up

pin up казино: pin up – pin up kz

pin up kz http://pinupaz.bid/# pin up azerbaijan

pin up

пин ап казино вход: пин ап 634 – pin up казино

пинап казино [url=http://pinupkz.tech/#]pin up kz[/url] пин ап казахстан

пин ап 634 http://pinupkz.tech/# пин ап казино онлайн

пин ап

pin up [url=http://pinupaz.bid/#]pin-up casino giris[/url] pin up azerbaijan

Hello! Quick question that’s totally off topic. Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly?

My site looks weird when viewing from my iphone.

I’m trying to find a theme or plugin that might be able to fix this issue.

If you have any suggestions, please share. Cheers!

пин ап кз https://pinupturkey.pro/# pin up guncel giris

пин ап казахстан

pin up casino giris: pin up giris – pin-up casino giris

pin up aviator [url=https://pinupturkey.pro/#]pin up guncel giris[/url] pin up guncel giris

zithromax 500mg: zithromax for sale online – where to get zithromax over the counter

Asking questions are really nice thing if you are not understanding something entirely, except this article provides fastidious understanding even.

where can i buy zithromax uk [url=https://zithromax.company/#]zithromax best price[/url] zithromax online pharmacy canada

http://semaglutide.win/# Rybelsus 14 mg price

price of amoxicillin without insurance: amoxil best price – amoxicillin without a doctors prescription

I do agree with all the ideas you have offered for your post. They’re really convincing and can certainly work. Nonetheless, the posts are very brief for novices. Could you please extend them a little from next time? Thanks for the post.

minocycline for rosacea: order stromectol – minocycline capsule

You can certainly see your skills in the work you write. The world hopes for more passionate writers like you who are not afraid to say how they believe. Always go after your heart.

It’s perfect time to make some plans for the future and it is time to be happy. I have read this post and if I could I desire to suggest you few interesting things or suggestions. Maybe you could write next articles referring to this article. I wish to read more things about it!

http://amoxil.llc/# amoxil pharmacy

zithromax pill

https://amoxil.llc/# amoxicillin generic

Thanks for another informative web site. Where else could I get that kind of information written in such an ideal way? I’ve a project that I am just now working on, and I’ve been on the look out for such info.

600 mg neurontin tablets: cheapest gabapentin – neurontin 800 mg pill

https://amoxil.llc/# how to buy amoxycillin

where can i buy zithromax in canada

generic amoxil 500 mg [url=https://amoxil.llc/#]cheapest amoxil[/url] amoxicillin order online

http://semaglutide.win/# Rybelsus 14 mg price

amoxicillin 500 mg tablets: amoxicillin cheapest price – buy amoxicillin online cheap

https://zithromax.company/# where to buy zithromax in canada

where can i buy zithromax capsules

Hello, i think that i saw you visited my web site so i came to ?return the favor?.I’m trying to find things to enhance my site!I suppose its ok to use some of your ideas!!

zithromax [url=https://zithromax.company/#]buy zithromax z-pak online[/url] buy zithromax

neurontin 400 mg capsule: gabapentin best price – neurontin prices generic

http://amoxil.llc/# amoxicillin 500 mg without prescription

https://amoxil.llc/# amoxicillin 500

how to get zithromax online

brand neurontin 100 mg canada [url=https://gabapentin.auction/#]neurontin 600[/url] neurontin 4 mg

Normally I don’t read article on blogs, but I would like to say that this write-up very compelled me to try and do so! Your writing style has been amazed me. Thank you, quite nice article.

I do agree with all of the ideas you have presented in your post. They’re very convincing and will definitely work. Still, the posts are very short for starters. Could you please extend them a little from next time? Thanks for the post.

It?s onerous to find educated folks on this subject, however you sound like you already know what you?re talking about! Thanks

https://gabapentin.auction/# buy neurontin 300 mg

zithromax capsules australia

can you buy zithromax over the counter in canada [url=http://zithromax.company/#]zithromax over the counter[/url] zithromax 250 mg

http://gabapentin.auction/# 32 neurontin

can you buy zithromax online: zithromax for sale – zithromax antibiotic

https://zithromax.company/# zithromax capsules australia

zithromax 250mg

ivermectin canada [url=http://stromectol.agency/#]order stromectol[/url] ivermectin price comparison

https://gabapentin.auction/# gabapentin generic

minocycline pac: stromectol best price – ivermectin cost australia

zithromax 500 mg [url=http://zithromax.company/#]zithromax for sale[/url] how to get zithromax

http://gabapentin.auction/# buy neurontin uk

zithromax 500mg

http://gabapentin.auction/# buy neurontin 100 mg

zithromax over the counter

Thanks for expressing your ideas right here. The other thing is that when a problem arises with a computer system motherboard, folks should not go ahead and take risk connected with repairing this themselves because if it is not done correctly it can lead to permanent damage to the entire laptop. It will always be safe just to approach the dealer of that laptop for that repair of motherboard. They have got technicians who may have an skills in dealing with laptop computer motherboard troubles and can make right analysis and perform repairs.

average cost of generic zithromax: zithromax for sale – zithromax 1000 mg online

can i buy zithromax over the counter in canada [url=http://zithromax.company/#]zithromax best price[/url] where can i purchase zithromax online

http://gabapentin.auction/# buy generic neurontin

Get Posotive reviews because You’re not on top, you’re missing out. Alfa Reviews offer real, high-quality positive reviews that stick, available on platforms like Google, Yelp, Trustpilot, Airbnb, TripAdvisor, and more. Studies show that potential customers read reviews before making decisions—so why not boost your credibility and rise to the top?

✔ Pay only for verified, successful reviews

✔ Affordable, risk-free service

✔ 100% legal, with genuine reviews

Don’t wait—improve your reputation now!

Get in Touch:

Email or WhatsApp Us: +1 (719) 403-7946

Direct WhatsApp Link: https://wa.me/qr/KRFK6LE53TDQJ1

neurontin 30 mg: cheapest gabapentin – neurontin 300

buy ivermectin uk [url=https://stromectol.agency/#]stromectol price[/url] stromectol south africa

https://semaglutide.win/# buy semaglutide online

zithromax capsules price

That’s why it’s all the more important to us that you are well informed! But Cam2Cam is not everything and you should also take a closer look at the other free live mature sex cams. For example, you can record the camsex shows with the sexcam recorder and even control a dildo live in the chat with the cam girl!

indian pharmacies safe [url=http://indianpharmdelivery.com/#]online shopping pharmacy india[/url] best online pharmacy india

non prescription erection pills https://indianpharmdelivery.com/# buy medicines online in india

online pharmacy india: reputable indian pharmacies – reputable indian online pharmacy

Thank you for this article. I will also like to talk about the fact that it can become hard while you are in school and merely starting out to initiate a long credit rating. There are many learners who are only trying to endure and have an extended or beneficial credit history can often be a difficult thing to have.

Hi! Do you know if they make any plugins to safeguard against hackers? I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any recommendations?

https://drugs24.pro/# ed drugs over the counter

indianpharmacy com

mexican mail order pharmacies [url=https://mexicanpharm24.pro/#]п»їbest mexican online pharmacies[/url] buying from online mexican pharmacy

mens erection pills https://drugs24.pro/# ed men

indian pharmacy online: mail order pharmacy india – buy prescription drugs from india

http://mexicanpharm24.pro/# purple pharmacy mexico price list

india pharmacy

online shopping pharmacy india: buy medicines online in india – pharmacy website india

cheap medication online: men with ed – impotance

india online pharmacy [url=https://indianpharmdelivery.com/#]online pharmacy india[/url] top 10 pharmacies in india

https://drugs24.pro/# herbal ed treatment

top 10 online pharmacy in india

Online medicine order: online pharmacy india – indian pharmacy online

Does your blog have a contact page? I’m having trouble

locating it but, I’d like to send you an e-mail.

I’ve got some suggestions for your blog you might be interested in hearing.

Either way, great site and I look forward to seeing it improve

over time.

prescription meds without the prescriptions [url=http://drugs24.pro/#]buy ed drugs online[/url] ed pills

http://indianpharmdelivery.com/# world pharmacy india

india pharmacy

comparison of ed drugs http://mexicanpharm24.pro/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

indian pharmacy [url=http://indianpharmdelivery.com/#]indianpharmacy com[/url] indian pharmacy paypal

erectial dysfunction http://drugs24.pro/# best treatment for ed

https://drugs24.pro/# erection pills that work

indian pharmacy online

buy medicines online in india [url=http://indianpharmdelivery.com/#]pharmacy website india[/url] best online pharmacy india

google viagra dosage recommendations http://drugs24.pro/# ed pills online pharmacy

paxlovid generic: best price on pills – paxlovid covid

buy Clopidogrel over the counter: here – antiplatelet drug

ivermectin otc: stromectol 1st shop – ivermectin 1 cream generic

Paxlovid buy online: check this – paxlovid pill

plavix best price [url=https://clopidogrel.pro/#]clopidogrel[/url] buy plavix

paxlovid generic: paxlovid shop – buy paxlovid online

Paxlovid over the counter: paxlovid pharmacy – paxlovid cost without insurance

http://stromectol1st.shop/# generic ivermectin cream

ed meds online canada

Today, considering the fast way of life that everyone is having, credit cards have a huge demand throughout the market. Persons coming from every area are using the credit card and people who are not using the credit card have prepared to apply for one in particular. Thanks for revealing your ideas about credit cards.

paxlovid buy: buy here – paxlovid pill

minocin 50 mg for scabies [url=https://stromectol1st.shop/#]best price shop[/url] ivermectin tablet 1mg

paxlovid covid: paxlovid price – paxlovid price

rybelsus price: order Rybelsus – order Rybelsus

paxlovid pharmacy: shop – paxlovid price

Clopidogrel 75 MG price [url=http://clopidogrel.pro/#]clopidogrel[/url] buy Clopidogrel over the counter

I am young and dirty and I think quite nice to look at. My tits are natural and my nipples are real cams show. Hehe now don’t keep me waiting and let’s go before someone else does and calls me.

antiplatelet drug: generic pills – buy Clopidogrel over the counter

Buy semaglutide: buy semaglutide online – semaglutide

paxlovid india [url=https://paxlovid1st.shop/#]buy here[/url] paxlovid india

buy clopidogrel online: clopidogrel pills – antiplatelet drug

Wow, this post is nice, my sister is analyzing these things, so I am going

to inform her.

minocycline 50mg pills online: cheapest stromectol – minocycline 100mg without prescription

minocycline 50mg tablets [url=https://stromectol1st.shop/#]stromectol 1st[/url] stromectol 3 mg tablet price

ivermectin lotion for lice: stromectol 1st shop – stromectol tablets buy online

Pornstar

paxlovid pill: best price on pills – paxlovid buy

minocycline 50 mg tablets for humans for sale: cheapest stromectol – minocycline 100

Buy semaglutide: Semaglutide pharmacy price – more

can you buy stromectol over the counter [url=https://stromectol1st.shop/#]buy online[/url] how much is ivermectin

buy clopidogrel bisulfate: Plavix 75 mg price – buy clopidogrel bisulfate

cheap plavix antiplatelet drug [url=http://clopidogrel.pro/#]clopidogrel pills[/url] Plavix generic price

Scam

1xbet скачать: 1xbet – 1xbet официальный сайт

пин ап: пинап – pin up kz